Introduction

The stomatognathic system includes various anatomical structures, which allow the mouth to open, swallow, breathe, phonate, suck and perform different facial expressions. These structures are the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), jaw and mandible, muscle tissues and tendons, dental arches, salivary glands, as well as the hyoid bone and the muscles that connect the latter to the scapula and the sternum, the muscles of the neck.

TMJ through its complex movements, on different orthogonal planes and multiple rotation axes, works in synergy with all the structures just listed. The TMJ must also work in coordination with the contralateral TMJ to coordinate tandem dynamic function.

Its position and structure make it an intersection of information and influences that expand throughout the body, and vice-versa; the mechanical information of other body districts can reflect in the TMJ.

The article reviews functional anatomy, embryological development, differences in the anatomy of the child and the adult, with a look at the surgical, clinical and other physiological variables that influence the temporomandibular function. The text reviews the manual approach to TMJ, which is often used as a support for joint rehabilitation, in synergy with the doctor.

Structure and Function

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is a diarthrosis, better defined as a ginglymoarthrodial joint. TMJ is composed of a synovial cavity, articular cartilage and a capsule that covers the same joint. We find the synovial fluid and several ligaments. The joint is the union of the temporal bone cavity with the mandibular condyle.[1]

Anatomy

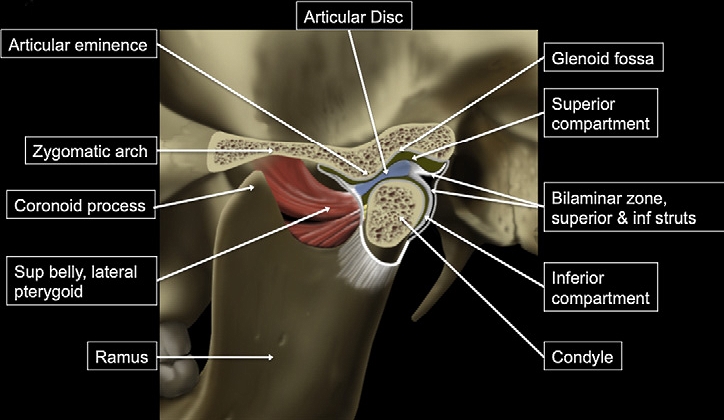

The cranial surface of TMJ consists of the squamous area of the temporal bone; it takes the name of glenoid fossa and welcomes the condyle of the jaw. The posterior area of the fossa is known as posterior articular ridge; sideways to the latter, we find a bone portion called postglenoid process. The postglenoid process area contributes to forming the upper wall of the external acoustic meatus.[1]

The anterior limit of the glenoid fossa of the temporal bone constitutes the articular eminence, which forms a medial bone prominence at the posterior border of the zygomatic bone. The preglenoid plane is slightly inclined, which leads into the articular eminence; the latter is anterior to the fossa, along with the base of the skull. The preglenoid plane is slightly inclined, which leads into the articular eminence; the latter is anterior to the pit, along with the base of the skull. This area allows and facilitates the movements of the articular disk and the condyle. On the lateral surface of the articular eminence, there is a bone ridge, known as the articular tubercle, near the root of the zygomatic process.

The glenoid fossa is wider in its mediolateral portion, compared to the anteroposterior area. The inferior articular surface of the glenoid fossa represents the superior area of the mandible.[1] It consists of the condyle of the mandible with a transverse diameter of about 15 to 20 mm and a measurement of about 8 to 10 mm in the anteroposterior direction.

The articular disc that covers the condyle and interposes below the glenoid fossa has a biconcave or oval shape; the cartilaginous disc has an anterior (about 2 mm) and posterior (about 3 mm) portion, with a thinner diameter in the middle. The anterior portion of the disk consists of a layer of fibroelastic fascia (above) and a fibrous layer (inferiorly). The upper portion is in contact with the postglenoid process, with the function of preventing the disc from slipping during the opening of the mouth. The lower portion of the disk has the task of avoiding excessive rotational movements of the disk relative to the mandibular condyle.

The anterior portion of the articular disk is in contact with: the joint capsule; articular eminence; condyle; the upper area of the lateral pterygoid muscle.

The posterior portion of the articular disk relates to: bilateral retro-disc tissue (behind the condyle), glenoid fossa; condyle; temporal bone.

The medial and lateral aspect of the cartilaginous disc is attached to the condylar formation of the mandible. The edges of the disc partly fuse with the fibrous capsule surrounding the joint.

Several ligaments manage the TMJ forces and send multiple proprioceptive afferents. The proprioception of the joint is provided by various components, such as the capsule, masticatory muscles, skin receptors and receptors within the periodontal ligaments. The tension perceived by the articular ligaments plays an important role in the function of TMJ.[2]

- Sphenomandibular ligament. The sphenomandibular ligament (SML) is a Meckel cartilage residue. It originates from the sphenoid spine (from which also originates the pterygospinous ligament) and in its path towards the jaw, is inserted in the medial wall of the TMJ joint capsule. Through the petrotympanic fissure, it involves the malleus and forms some fibers of the anterior ligament of the malleus. It continues its descent to attach itself to the lingula of the mandible (sphenoid, middle ear, jaw). The mylohyoid nerve and several vessels cross the ligament; has contacts with the pterygomandibular fascia. It is in a superior and lateral relationship with the lateral pterygoid muscle, the internal maxillary artery and the auriculotemporal nerve, the inferior alveolar nerve, and the medial meningeal artery. Its main task is to protect the TMJ from an excessive translation of the condyle, after 10 degrees of opening of the mouth.

- Stylomandibular ligament. The stylomandibular ligament (STML) arises from the styloid process of the temporal bone up to the posterior margin of the jaw or the jaw angle. It is considered a thickening of the deep cervical fascia (in particular of the parotid fascia). It serves to limit excessive protrusion of the jaw. Its embryological derivation concerns the first and second branchial arch, from which the middle ear stapes will derive (through the Reichert cartilage). In its path, it covers the inner portion of the medial pterygoid muscle.

- Pterygomandibular ligament. The pterygomandibular ligament or raphe (PTML) is a thickening of the buccopharyngeal fascia. It arises from the apex of the hamulus of the internal pterygoid plane of the skull up to the posterior area of the retromolar trigone of the mandibular bone. Some muscles are in contact with PTML: the buccinator muscle (anterior) and the pharyngeal constrictor muscle (posteriorly). Embryologically, the ligament derives from the mesenchymal connection of two branchial arches (first and second). PTML limits excessive jaw movements.

- Pinto or malleolomandibular or discomalleolar ligament. From an embryological point of view, it derives from the tympanic portion. The ligament has two portions. The first concerns the middle ear involves the malleus relative to the anterior ligament of the malleus; the second involves the extra-tympanic area, that is, the portion of the TMJ joint capsule, posterosuperior, in contact with the retro-discal tissues (passing through the petro-tympanic fissure). The functions are twofold. For TMJ protects the synovial membrane with respect to the tensions of surrounding structures. For the middle ear, it would seem to manage or influence adequate pressure for this area of the ear.[3][4]

- The collateral ligament consists of 2 bundles of symmetrical fibers that originate at the level of the intermediate fascia of the articular disk and insert at the medial and lateral poles of the mandibular condyle. It serves to anchor the disk to the condyle.[5][6]

TMJ is related to different muscles that have the function to move and protect the joint itself. The muscles that function to close the jaw are masseter, temporal, lateral or external pterygoid. The muscles that open the jaw are medial or internal pterygoid, geniohyoideus, mylohyoideus; digastric.

Function

When the mouth opens there is a combination of rotational movement of the discomandibular space and action of the translational discotemporal space; the rotation occurs before the translation. The condyle can move laterally through a rotation and then an anterior sliding of the same condylar structure, and an anterior translation/rotation in the medial direction of the opposite condyle. The condyle can move backward, while the opposite condyle slides forward. The bilateral or ipsilateral TMJ protrusion occurs by anterior sliding

The complex movements of TMJ allow multiple functions:

- Chewing

- Sucking

- Swallowing

- Phonation

- Facial expressions

- Breathing

- Protrusion, retrusion, lateralization of the jaw

- Opening the mouth

- Maintain the correct pressure of the middle ear

Embryology

TMJ derives from the first pharyngeal arch, where we can recognize a mesodermal part (muscles and vessels) and mesenchyme (from neural crests) for bones and cartilages. The development of TMJ divides into three stages: the blastemic stage; the cavitation stage and lastly, the maturation stage.[1]

- Blastemic stage. It begins in the seventh/eighth week of gestation, where the formation of the glenoid fossa and condylar blastema occurs (a group of cells that remain long undifferentiated and, proliferating, give rise to sketches of organs)

- Cavitation stage. The formation of the lower joint space begins. The blastemas start to differentiate into multiple layers, to form the lower synovial layer and what will become the joint disk; this happens between the ninth and tenth weeks of gestation

- Maturation stage. The upper joint space begins to form towards the eleventh week of gestation. TMJ will continue to form until the baby is born. Around 17 weeks the joint capsule is formed, while at 19 to 20 weeks the development of the cartilage inside the capsule can be recognized.[1]

The morphology of the glenoid fossa and the condyle will be under the influence of the mechanical forces of the vessels and neighboring muscles. At birth, TMJ, compared to other types of synovial joints, is not fully developed. The jaw will begin to develop from the fourth week. TMJ develops simultaneously with the ear.

The child has a more obtuse mandibular arch, compared to the adult, which has a more angular shape; in the baby, the glenoid fossa is looser and, the cartilage is not yet present, but there will be a fibrous connective tissue. Between 5 and 10 years of age, the condyles grow in a posterior, lateral, and upward direction; the joint shape will be further managed by the mechanical forces of the teeth and the chewing muscles.[1]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Arterial blood supply to TMJ is ensured by the superficial temporal artery and the maxillary artery, as well as by the masseteric artery. There are other arterial branches, such as the posterior auricular artery and the ascending pharyngeal artery (derived from the external carotid artery), and from the ascending palatine artery.[7]

The venous drainage occurs through the pterygoid plexus in the retrodiscal area, in communication with the internal maxillary vein, the sphenopalatine vein, the medial meningeal veins, the deep temporal veins, the masseterine veins, and the inferior alveolar vein.

Lymphatic drainage is not always straightforward to describe because, in the case of TMJ disease, lymph nodes can increase in number. Generally, the lymphatic system that affects TMJ comes from the area of the submandibular triangle.

Nerves

TMJ has several proprioceptive receptors, in particular in the parenchyma of the articular disk: Golgi-Mazzoni and Ruffini; myelinated and nonmyelinated nerve fibers.

The articular capsule in the anterolateral portion receives innervation by the masseteric nerve, a branch of the second branch of the trigeminal nerve. The lateral area of the capsule, on the other hand, is innervated by the auriculotemporal nerve of the third branch of cranial nerve V.[8][9]

Muscles

The muscles that make direct contact with TMJ are four: masseter, temporal, and two pterygoids.

- The masseter muscle with its perimysium has direct contact with the articular disc on the front edge. It originates from the zygomatic arch with several muscular layers and inserts on the branch of the mandible (lateral surface) and the coronoid process (lateral surface).

- Its primary task is to elevate the jaw. The innervation of the muscle is through the masseteric branch of the trigeminal cranial nerve). The temporalis muscle originates from the temporal fossa of the skull and the medial face of the zygomatic process; it inserts on the coronoid mandibular process. Like the previous muscle, the temporalis sometimes makes contact with the articular disc anteriorly. It elevates the mandible. It receives innervation by the branches of the trigeminal, third branch (deep temporal nerves).

- The lateral or external pterygoid muscle consists of an upper head and a lower head. The upper bundle originates from the extracranial face of the large sphenoid wing to be inserted anteromedially to the joint capsule and/or the anteromedial face of the condyle neck in the upper portion of the pterygoid fovea. It contacts the disc at the anteromedial aspect. The inferior head originates from the lateral aspect of the lateral lamina of the pterygoid process of the sphenoid and inserts itself on the pterygoid fovea. Bilateral activation of the external pterygoid, protrudes the mandible, while, if activated unilaterally, causes contralateral lateral deviation of the mandibular bone. The external pterygoid muscle pulls the condyle forward in the opening phase of the mouth; anteromedially it pulls the disc in the closing phase. The two upper and lower bundles are active in the early stages of opening and in the first stages of closing the mouth. The internal or medial pterygoid muscle originates from the pterygoid fossa, from the pyramidal process of the palatine, and from the maxillary tuberosity, to terminate on the medial face of the angle and of the mandibular branch. Like the external pterygoid, the internal pterygoid is innervated by the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve. The internal pterygoid muscle elevates and protrudes the mandible.[5]

Physiologic Variants

Pneumatization of the articular tubercle is an anatomical variant of TMJ. Consists of bone cavities/air cells in the root of the zygomatic arch and/or in the tubercle or eminence of the temporal bone. These cavities may be present only ipsilaterally or bilaterally. Normally these cavities are reabsorbed during puberty, but it may happen that the reabsorption does not occur. It does not seem that this variability could negatively affect the symptomatology or function of TMJ.[10]

Surgical Considerations

Surgical procedures for TMJ are performed for various medical reasons: local and/or systemic disease; trauma; alteration of joint morphology and loss of function. The surgical approach depends on the present problem, on the anatomical physiology, the psycho-emotional need of the patient, the experience of the surgeon, and the pre-surgically pre-established objectives.

Orthognathic surgery in the presence of aesthetic/functional problems, for example, mandibular advancement or to increase the function of the joint in opening the mouth, or to avoid joint dislocation, do not give definitive conclusions in the benefit-side effects relationship. Probably, postoperative functional results are more effective if TMJ itself is free of concomitant pathologies (arthritis, arthrosis, etc.).[11][12]

We know little of what happens after the surgical approach in the presence of synovial plicae to TMJ, and often, the presence of this functional alteration may not give symptoms. The plica is discovered only after an instrumental examination.[13]

Total joint reconstruction interventions or with alloplastic joint replacement appear to have good post-surgical results in the presence of idiopathic condylar resorption.[14][15]

Approaches with arthroscopic seem to achieve good results regarding the repair or removal of the joint disk.[16]

Clinical Significance

Many pathologies can impact the TMJ and potentially cause varying degrees of clinical dysfunction. These conditions include but are not limited to[17]:

- Rheumatoid arthritis: crepitus, limited ROM, increased stiffness, pain, joint sounds

- Psoriatic arthropathy: joint sounds, morning stiffness, pain

- Ankylosing spondylitis: joint sounds, pain in the lateral pterygoid muscles, hypertrophy of the masseter muscle, limitation of the ROM

- Pain: articular sounds.

- Fibromyalgia syndrome: myalgia, pains of TMJ

- Muscular pain

- Multiple sclerosis: myalgia pains of TMJ, pain during the movement of the mouth

Clinical evaluation begins by observing the patient's natural movements. The evaluation includes the observation of the symmetry of the face and the movements of TMJ as well as when the pain appears (at which articular degree of opening or closing and accessory movements), and the entity of the pain and if a joint sound appears.

The muscles are palpated (internally and externally), the presence of enlarged submandibular lymph nodes is also checked by palpation. Next comes testing the strength of the muscles, individually, and during complex movements. The operator passively moves the jaw, using a glove, to evaluate the TMJ ligament apparatus. We look inside the mouth to check for anatomical anomalies. The fingers are placed on the joint while the patient opens his mouth to evaluate further anomalies. Always with the fingers in support of the TMJ, it is asked to pull out the tongue, turn and flex/extend and incline the neck, during the opening of the mouth; this is to verify any accentuations of TMJ dysfunction, in association with other muscle-joint districts.

Some tools can improve the measurement of the ROM of the mouth, such as the Boley gage and the TheraBite range of motion scale. These evaluations have their basis in the research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (RDC/TMD), updated to 2016.[18]

In children with a type II class, they have a higher percentage of TMJ dysfunction; this dysfunction in the growth phase will result in an asymmetry of the mandibular branch.

Instrumental assessments are critical to a safe diagnosis and are necessary before taking a therapeutic approach to a TMJ in dysfunction.[19]

Panoramic radiography. Allows evaluation of the mandibular condyles corresponding glenoid fossa relationship.

Multi-slice computed tomography or cone-beam computed tomography. To evaluate the morphology of the components that make up TMJ, as well as bone position and pathologies.

Magnetic resonance image. It is possible to observe the condition of the articular disk, anatomy, function, and form.

Other Issues

Several temporomandibular disorders symptoms (approximately 85-90%) are treated with non-invasive, non-surgical approaches. Non-invasive approaches include manual physiotherapy and osteopathy, patient education, medication, and splint therapy.[20][21]

AN issue generating much debate is the relationship between TMJ function and anatomy and posture. The difficulty in positively affirming the existence of a relationship between posture and TMJ is a function of the anatomical complexity of the same joint (capsule, muscles, ligaments, nerves, disk) and the comparison with all that is the body. Not only. Research is not yet able to find the correct unit of measurement or the ideal tool for measuring the relationship between TMJ and posture. It is necessary to consider the patient's historical variables and how long the patient has articulation dysfunctions.

There is a relationship between TMJ function and the cervical-hyoid-scapula tract.[22] Patients with TMJ dysfunction have abnormal plantar support pressure compared to people without TMJ alterations.[23][24]

Degenerative diseases of this joint represent the second major musculoskeletal problem (pain and reduced movement). Aging is one of the most important causes of diseases related to TMJ dysfunction. According to the geroscience hypothesis, trying to delay changes related to aging (delaying the cellular senescence of muscle-joint tissues and the secretion of cytokines) would be possible to delay or prevent the onset of TMJ dysfunctions. According to some authors, the intake of substances such as quercetin (antioxidant) and dasatinib (anticancer drug) could slow down the degeneration of TMJ. [25]

According to a recent study, in patients suffering from temporomandibular joint dysfunction, chewing muscles have greater electrical activity than subjects without TMJ disorders. [26]