Continuing Education Activity

Adrenal myelolipomas represent benign adrenal neoplasms primarily consisting of mature adipose tissue intertwined with myeloid tissue. They constitute a noteworthy portion, ranging from 6% to 16%, of adrenal incidentalomas, emerging as the second most frequent etiology following adrenal adenomas. These lesions can exhibit functional or nonfunctional characteristics, adding a layer of complexity to their clinical evaluation and management.

This continuing education activity is designed to provide a comprehensive review of the assessment and treatment of adrenal myelolipomas. Additionally, it emphasizes the crucial role of the interprofessional healthcare team in recognizing and effectively managing patients with adrenal myelolipomas. By enhancing our collective understanding of these lesions and promoting interdisciplinary collaboration, we can optimize patient care, refine diagnostic strategies, and tailor treatment plans to individual patient needs.

Objectives:

Differentiate between adrenal myelolipomas and other adrenal lesions through a standardized diagnostic approach, taking into account size, symptomatology, and risk factors to guide appropriate management decisions.

Screen patients with suspected adrenal myelolipomas for hormonal hypersecretion, employing relevant laboratory tests to identify potential endocrine abnormalities associated with these neoplasms.

Implement evidence-based guidelines for the surgical resection of adrenal myelolipomas, considering criteria such as neoplasm growth, size, symptomatic pain or mass effect, suspicion of malignancy, or hormonal hypersecretion.

Coordinate long-term follow-up care for patients with adrenal myelolipomas with primary care providers and other team members, including regular monitoring and timely intervention as necessary.

Introduction

Adrenal myelolipomas are benign, nonfunctional adrenal neoplasms predominantly composed of mature adipose tissue and intermixed myeloid tissue. They comprise 6% to 16% of all adrenal incidentalomas and are the second most common cause of adrenal lesions after adrenal adenomas.[1]

The increased prevalence of adrenal myelolipomas is primarily due to markedly increased detection because of the wider accessibility and usage of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans for unrelated reasons. The pathogenesis of adrenal myelolipoma is believed to either be due to metaplastic change in the mesenchymal cells or to overstimulation by adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH).[1]

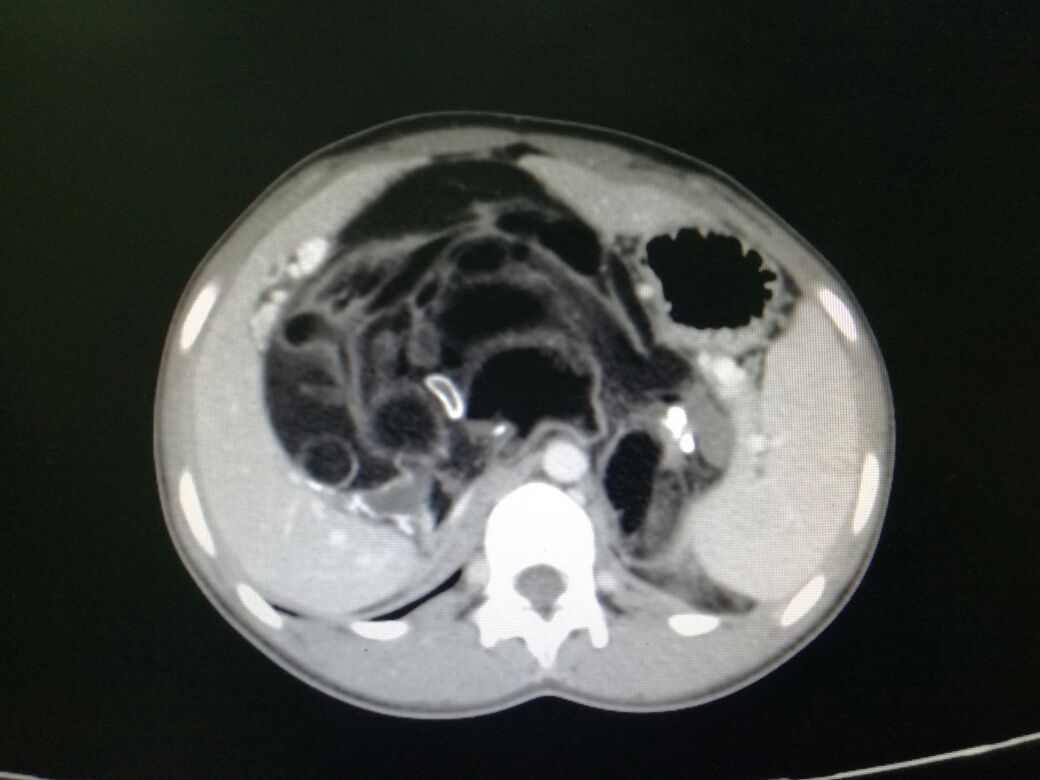

Clinically, they are usually small and asymptomatic but may present with abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting. On CT scan, they appear as well-circumscribed, hypodense masses with an attenuation of 90 to 120 Hounsfield units (HU) or lower, depending on their fat content.[2][3][4]

Myelolipomas are rarely encountered outside the adrenal glands and are termed extra-adrenal myelolipomas, most often found in the retroperitoneum, thorax, or pelvis.[1] Surgical resection is indicated in cases of significant adrenal neoplasm growth (>1 cm in defined time period), size >7cm due to chance of rupture and bleeding, symptomatic pain or mass effect, suspicion of malignancy, or hormonal hypersecretion.[1][5]

Etiology

The pathogenesis of adrenal myelolipomas is not definitively known, but many studies show a relation to ACTH stimulation. One hypothesis suggests that stimuli such as necrosis or inflammation could lead to the metaplasia of the reticuloendothelial cells, which could lead to the development of adrenal myelolipomas. The increased lesion incidence in the advanced years of life supports this hypothesis.[1][6]

Another theory is that embryological origins may contribute to myelolipoma development. In fetal circulation, until the bone marrow is fully mature, adrenal tissue is capable of hematopoiesis, and this is also present in adults with chronic anemia or hematologic disorders, such as thalassemias, hereditary spherocytosis, or sickle-cell anemia.[7] This finding is also supported by reports of large doses of erythropoietin-stimulating agents causing bilateral adrenal myelolipomas.[7]

Lastly, in an important historical study, Seyle and Stone noted that injection of crude anterior pituitary extract in rats leads to the transformation of the adrenal cortex into bone marrow-like tissue. In addition, the administration of "testoid components" in rats caused the formation of pure adipose tissue, and the administration of corticotrophic anterior pituitary extracts intensified this effect.[8] Therefore, it was hypothesized that excess ACTH could be responsible for the pathogenesis of adrenal myelolipomas. This theory is supported by the increased incidence of adrenal myelolipomas in congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), where the levels of ACTH are usually significantly elevated.[1][6] Patients with genetically proven CAH may have up to a 36% incidence of adrenal myelolipomas. These lesions were also more likely to be bilateral and larger at diagnosis.[7] This finding is not generally seen in primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison's disease), which is also associated with high levels of ACTH, likely due to insufficient activity of functional adrenal tissue.[7]

Adrenal myelolipomas have also been found to have a specific micro-RNA signature compared to other adrenocortical tumors. This may be important in the translation of messenger RNA signals to myelolipoma formation and may be an additional biomarker to evaluate.[7]

Adrenal myelolipoma is sometimes associated with conditions like Cushing disease, obesity, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes, which can be considered adrenal stimulants. Other theories propose that a stressful lifestyle and an unbalanced diet may also play a role in the natural history of the neoplasm.[1][6]

Epidemiology

About 80% of all adrenal incidentalomas are nonfunctional, and over 90% are benign. Adrenal myelolipomas are the second most common adrenal lesions, comprising 6% to 16% of all adrenal incidentalomas.[1][9][10] The incidence is much higher in patients with CAH; however, the Endocrine Society does not recommend routine screening for adrenal tumors in these patients.[7]

Adrenal myelolipomas have an approximate autopsy prevalence of 0.08 to 0.2%.[1] They are usually diagnosed in those aged 40 to 70 years, with a median age of diagnosis around 62 years.[1][11] There is no gender predilection, but some studies suggest a slight preference for the right side.[11]

Pathophysiology

Adrenal myelolipoma size can range from a few millimeters to greater than 10 cm. Those larger than 10 cm in size are called giant adrenal myelolipomas and are exceedingly rare.[12][13] The largest adrenal myelolipoma reported to date weighed 6 kg.[14]

While generally considered nonfunctional, 10% to 15% of myelolipomas may be hormonally active. In addition, 6% of adrenal myelolipomas are associated with functioning or nonfunctioning adrenal adenomas. An endocrine workup is warranted if symptoms, signs, or lab abnormalities are present.[7]

Histopathology

On gross pathologic examination, a cut section of a myelolipoma has a variegated appearance consisting of bright yellow areas of fat, dark red areas of trilinear hematopoietic myeloid tissue, and areas with intermixed red and yellow components. The fat content varies but concentration is typically 25% to slightly more than 50%. Areas of necrosis and calcification are common.[10][15]

On histopathologic examination, myelolipomas predominantly comprise fatty areas with interspersed hematopoietic tissue components and stem cells. These fatty elements and hematopoietic areas may be clearly separated or are often intermixed.[16] Tissue analysis will stain positive for an amalgamation of myeloid cells, erythroid cells, and megakaryocytes. In an isolated adrenal myelolipoma, a peripheral rim of normal adrenal cortical tissue can be commonly identified distinctly from the mass.[7][17]

History and Physical

Most Common Presenting Symptoms for Adrenal Myelolipomas

Dyspnea, back pain, fever, unexplained weight loss, and virilization can be the presenting symptoms of an adrenal myelolipoma. Patients with lesions larger than 6 cm are more likely to present with bilateral disease and symptoms of mass effect, eg, abdominal, flank, or back pain and positional shortness of breath.[1] Rupture of adrenal myelolipomas occurs primarily in those larger than 8 cm.[7]

Four Recognizable Clinicopathologic Patterns of Adrenal Myelolipomas

Isolated Adrenal Myelolipoma

- Myelolipomas occurring in an otherwise normal adrenal gland are the most common pattern of presentation. They are asymptomatic and are incidentally identified during the imaging investigation performed for some other reason.

Adrenal Myelolipoma with Acute Hemorrhage

- Retroperitoneal hemorrhage is the most common complication occurring in adrenal myelolipoma. Isolated larger lesions (typically over 4 cm in size) and those predominantly composed of fat (greater than 50%) have a greater propensity for a hemorrhagic event.

Extra-Adrenal Myelolipoma

- Myelolipomas outside the adrenal gland are most commonly found in the retroperitoneum, where presacral or perirenal locations are reported as the most common. Patients usually have no endocrine abnormalities or acute hemorrhage.

Adrenal Myelolipoma with Associated Adrenal Disease

- Patients with adrenal myelolipoma may have a separate endocrine disorder: hypercortisolism (Cushing syndrome), congenital adrenal hyperplasia, and primary hyperaldosteronism have been reported in patients with symptomatic adrenal myelolipomas.

Evaluation

As these tumors are often nonfunctional, endocrinological tests are helpful to exclude functional adrenal masses, such as pheochromocytomas, from the differential diagnosis. The lesions usually present as low-attenuation fat interspersed with higher-attenuation myeloid components that appear cloudy, as strands, or as a nodule.

Symptoms of a functional adrenal neoplasm would include the following examples of a potential hormonal excess:

- Diabetes

- Fatigue

- Muscle weakness (especially proximal muscle)

- Obesity

- Uncontrollable severe hypertension

- Unexplained significant weight gain

- Unusual feminization

- Virilization

Ultrasonography, CT scans, and MRI scans are all helpful in diagnosing adrenal masses such as myelolipomas, with CT scans being the most sensitive for identifying fat within the lesions. As mentioned earlier, adipose tissue makes up variable amounts of adrenal myelolipoma, readily detectable and measurable on CT scans.[10][15] The myeloid component is usually contrast-enhancing.

If noncontrast CT demonstrates a lesion with a density of less than 10 Hounsfield units (HU) and endocrinological evaluation is negative, it has been suggested that a biopsy can be avoided. However, up to 12% of myelolipomas may be functional.[7] The differential diagnosis of fat-containing, nonfunctional retroperitoneal masses includes retroperitoneal lipomas, liposarcomas, and renal angiomyolipomas.

Ultrasound

- Myelolipomas have a typical appearance of a hyperechoic mass with intermixed hypoechoic regions. The variable proportions of the elements in the lesion mainly determine echogenicity. The areas of intermixed fatty and myeloid tissue are the most echogenic, whereas regions of pure fat may appear hypoechoic.[14][18]

- Foci of calcification appear hyperechoic with acoustic shadowing. Myelolipomas have vague or no appreciable margins on ultrasound, as their sonic density is similar to the surrounding retroperitoneal fat.[14][18]

- Hemorrhage alters the sonographic picture, with hemorrhagic areas appearing hypoechoic compared with fat.[18][19][20]

CT Scan

- CT is the preferred imaging modality for diagnosing adrenal myelolipomas and is the most sensitive imaging modality for detecting hemorrhage, which may be hyper or hypodense, depending on the age.

- Large amounts of fat are frequently encountered with “smoky” or "variegated" areas of interspersed higher-attenuation tissue. This denser tissue has attenuation values of 20 HU to 30 HU, inferring the presence of both fat and myeloid elements.[14][18]

- Myelolipomas are usually relatively well-circumscribed; however, due to the presence of abundant fat, they can be difficult to distinguish from surrounding retroperitoneal adipose tissue.[14][18]

- Foci of punctate calcification may be seen in 25% to 30% of cases.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- The predominantly fatty areas in myelolipomas appear hyperintense on T1-weighted MRI scans and intermediate to hyperintense on T2-weighted scans. Admixed marrowlike elements have medium-intensity signals similar to that of the spleen.[18]

- Fat-suppression techniques are best for demonstrating the fat in a myelolipoma with MRI. The presence of marrow-like elements or hemorrhage results in persistent areas of increased signal intensity on fat-suppressed MRI.[21]

- The imaging features of extra-adrenal myelolipomas are similar to those of adrenal myelolipoma and do not allow the distinction of an extra-adrenal myelolipoma from other fat-containing tumors.[18]

Due to the accurate ability of the different imaging modalities in diagnosing myelolipomas, biopsy is often unnecessary. Exceptions would be indeterminate imaging or features suggestive of adrenal carcinoma or liposarcoma.[7]

Treatment / Management

Management of adrenal myelolipomas should be determined based on the size of the lesion, the presence of any indications of possible malignancy, and the presence of symptoms. If there is any reasonable suspicion of a malignancy, the lesion should be treated surgically, but the treatment is usually conservative for most adrenal myelolipomas.[16]

Small (<5 cm) nonfunctional lesions in asymptomatic patients are usually monitored with repeat imaging 6 months after the initial diagnosis and then yearly for 1 to 2 years. Some guidelines recommend annual imaging and biochemical testing for up to five years because a small percentage (<10%) may develop late hormonal functionality.

Any significant enlargement on repeat imaging, defined as 1 cm or more, or the development of hormonal functionality indicates the need for surgical resection. Most nonfunctional adrenal masses remain stable in size and never develop any significant hormonal activity.[22]

Symptomatic tumors, masses that are actively enlarging, hormonally active adrenal neoplasms, imaging that is suspicious for malignancy or local invasion, evidence of possible tumor rupture, active retroperitoneal bleeding, or myelolipomas larger than 6 cm should undergo elective surgical excision. The American Urological Association recommends surgical excision if the mass exceeds 5 cm.[5][23][24][25][26]

This approach is based on the reported incidence of life-threatening emergencies caused by spontaneous rupture and hemorrhage within large lesions and long-term experience with a conservative approach to smaller, asymptomatic lesions. Also, adrenal masses larger than 6 cm have a 25% chance of an adrenal malignancy, a further indication for surgery.[27]

- Conventional or endoscopic access may be chosen according to the tumor size. Minimally invasive and endoscopic techniques are best utilized for smaller-sized lesions, depending on the operator's expertise. Conventional surgery is usually preferred for larger masses.[28]

- An extraperitoneal approach is preferable as it leads to quicker recovery of the patient and fewer postoperative complications.

- The midline approach is indicated for masses larger than 10 cm or in cases with adhesions and infiltration of the surrounding structures.

- Follow-up is mandatory regardless of which treatment method has been employed.

Summary of Indications for Surgical Excision

- Active retroperitoneal bleeding

- Evidence of possible local invasion

- Hormonally active (functional) lesions

- Possible tumor rupture

- Suspicion of malignancy

- Symptomatic tumors (pain or discomfort)

- Tumors larger than 6 cm

- Tumors that are actively enlarging (1 cm or more)[5]

Monitoring of Myelolipomas

Monitoring is appropriate for patients with myelolipomas that do not meet the criteria for surgical excision. These would typically be small (<4-5 cm), nonfunctional, asymptomatic adrenal lesions with significant fat content.

Such monitoring would include the following American Urological Association Core Curriculum Recommendations:[22]

- Initial biochemical testing that is negative for hormonal activity.

- Repeat imaging and biochemical testing 6 months after the initial diagnosis and then yearly for at least 1 to 2 years.

- Some guidelines recommend the annual imaging and biochemical testing continue for up to 5 years because a small percentage (<10%) may develop late hormonal functionality.

- Most lesions (75%-95%) remain stable in size over time, and less than 10% ever become hormonally active after initial negative testing.

Other professional societies have different recommendations for monitoring adrenal myelolipomas.[29][30]

- The 2016 European Society of Endocrinology and European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors guidelines do not recommend any follow-up imaging or biochemical testing if the initial workup shows a small lesion (<4 cm) with very low density (<10 HU on CT). If the lesion is greater than 4 cm or has indeterminate characteristics, then repeat imaging at 6 to 12 months is recommended.[29]

- The American College of Radiology guidelines are similar to the above except for a recommendation for a risk-stratified approach to further evaluation (PET-CT, biopsy, or surgery as appropriate) for adrenal masses less than 4 cm with indeterminate radiological characteristics.[30]

Differential Diagnosis

Adrenal myelolipomas are typically nonfunctional; endocrinological testing can exclude functional adrenal masses. The remaining nonfunctional masses would include the following:

Benign adrenal adenoma: These are the most common adrenal incidentalomas. They are well-circumscribed, homogenous masses that have low attenuation in most cases. This low attenuation is due to the fatty tissue present in most adenomas. Lipid-poor adenomas can be observed with a greater attenuation value. While most adrenal adenomas are nonfunctional, some may be active endocrinologically.[31][32] See our companion StatPearls reference article on "Adrenal Adenoma."[31]

Adrenal carcinoma: These are large, lobulated tumors with a heterogeneous appearance due to hemorrhage and necrosis. They have irregular margins and invade the surrounding structures—inferior vena cava, kidney, and liver. They have an attenuation value greater than 10 HU and show increased uptake on the PET scan.[33] See our companion StatPearls reference article on "Adrenal Cancer."[33]

Retroperitoneal liposarcoma: This is a slow-growing tumor of the retroperitoneal region, composed of adipocytes, and radiologically appears similar to an adrenal myelolipoma.[32][34]

Renal angiomyolipoma: Angiomyolipomas are tumors comprised of fat, blood vessels, and muscle cells. These are large, heterogeneous-appearing tumors that can invade through the renal capsule. The radiological appearance is similar to that of an adrenal myelolipoma with negative attenuation values; however, they arise from the kidney.[32][35] See our companion StatPearls reference article on "Renal Angiomyolipoma."[35]

In addition, any retroperitoneal mass can be included in the differential diagnosis, such as retroperitoneal lymphoma, lipoma, or metastatic disease. Given their significant vascularity, the adrenal glands are especially prone to metastatic disease.

Prognosis

Prognosis of adrenal myelolipoma is generally good. One series followed 163 patients for a median of 7 years, and only 16% of patients showed a growth ≥1 cm.[7] Those who meet the criteria for surgery also do well, as there is no reported malignant potential.[5] Long-term survival with no recurrence of myelolipoma has been reported.[36]

Complications

The primary complications of adrenal myelolipomas include pain and mass effects. Hemorrhage and rupture are rare and occur when size exceeds 8 cm to 10 cm. If surgery is required, standard complications may accompany laparoscopic or open surgical procedures.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with adrenal myelolipomas should be educated about the disorder, options available for treatment, possible diagnostic procedures, suggested follow-up, and indications for surgical intervention. Patients can be assured that the condition is usually benign and can be treated conservatively.[1][5]

Pearls and Other Issues

Functional tests for abnormal adrenal activity may include the following, as appropriate:[37][38][39][40]

- Plasma ACTH, AM cortisol, aldosterone, androstenedione, 17-beta-estradiol, metanephrine, normetanephrine, 1 mg overnight dexamethasone suppression test, DHEAS, potassium, 17-OH-progesterone, renin, and testosterone (total and free).

- Sex hormone testing is warranted in feminization, virilization, suspected adrenal carcinoma, or the evaluation of adrenal masses > 4 cm.

- Adrenal vein sampling may be needed in selected cases.

- A 24-hour urine test for aldosterone, catecholamines, free cortisol, metanephrine, and vanillylmandelic acid.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Providing patient-centered care for individuals with adrenal myelolipoma requires a collaborative effort among healthcare professionals, including physicians, advanced practice practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and others. First and foremost, healthcare providers must possess the necessary clinical skills and expertise when diagnosing, evaluating, and treating this condition. This includes proficiency in interpreting radiological findings, recognizing potential complications, and understanding the nuances of managing functional and nonfunctional myelolipomas. Urology or general surgery may require consultation depending on the size and location of the myeloplipoma. Moreover, a strategic approach involving evidence-based guidelines and individualized care plans tailored to each patient's unique circumstances is vital.

Ethical considerations come into play when determining treatment options and respecting patient autonomy in decision-making. Responsibilities within the interprofessional team should be clearly defined, with each member contributing their specialized knowledge and skills to optimize patient care. Effective interprofessional communication fosters a collaborative environment where information is shared, questions are encouraged, and concerns are addressed promptly.

Lastly, care coordination is pivotal in ensuring seamless and efficient patient care. Physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals must work together to streamline the patient's journey, from diagnosis through treatment and follow-up. This coordination minimizes errors, reduces delays, and enhances patient safety, ultimately leading to improved outcomes and patient-centered care that prioritizes the well-being and satisfaction of those affected by adrenal myelolipoma.