Continuing Education Activity

Histoplasma capsulatum is a dimorphic fungus present worldwide in pockets of endemicity particularly associated with river valleys. The endemic regions in the United States are Ohio and Mississippi river valleys as well as southeastern states. It is a soil-based fungus, and when it is disturbed, the conidia become airborne and can be inhaled. Often the infections are asymptomatic, but a granulomatous inflammation results in pulmonary disease akin to pulmonary tuberculosis. In immunocompromised patients, histoplasmosis can become disseminated and lead to considerable morbidity and mortality. This activity reviews the epidemiology of histoplasmosis and the role of the interprofessional team in managing patients with the diagnosis.

Objectives:

- Identify the epidemiology of histoplasmosis.

- Describe the presentation of patients with histoplasmosis.

- Outline the treatment and management options available for histoplasmosis.

- Summarize interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance the diagnosis and treatment of histoplasmosis to improve outcomes.

Introduction

Histoplasma capsulatum (Hc) is a dimorphic fungus present worldwide in pockets of endemicity particularly associated with river valleys. The endemic regions in the United States are Ohio and Mississippi river valleys as well as southeastern states. It is a soil-based fungus, and when it is disturbed, the conidia become airborne and can be inhaled. Often the infections are asymptomatic, but a granulomatous inflammation results in pulmonary disease akin to pulmonary tuberculosis. In immunocompromised patients, histoplasmosis can become disseminated and lead to considerable morbidity and mortality.[1][1][2][3]

Etiology

In 1905, a pathologist, Samuel Darling, named H. capsulatum; so it also is known as Darling disease. Twenty years later Histoplasma yeast was isolated, and its dimorphic nature determined. At body temperature, H. capsulatum was yeast, but at ambient temperatures (25 C) it exists as a mold. H. capsulatum likes moist soil, particularly with decaying guano. Bats carry the fungus in their gastrointestinal tract, and birds carry H. capsulatum on their feathers. Birds are not affected by H. capsulatum due to their high body temperatures (40 C). Outbreaks have occurred where there was intense construction activity in endemic regions.[4][5][6][7]

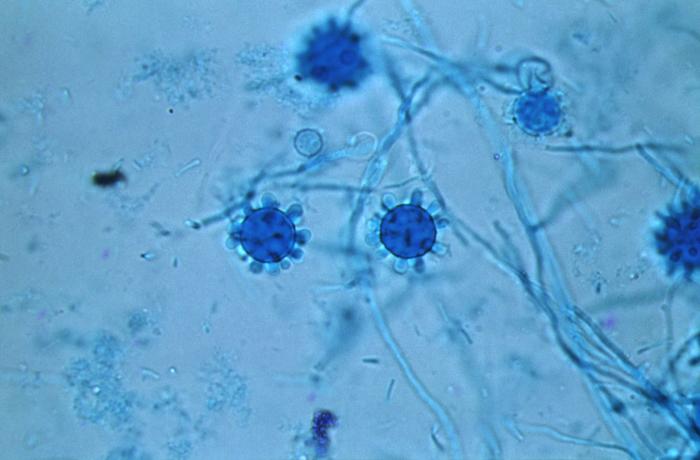

H. capsulatum is a member of the family ascomycetes and exists as two mating types. While in nature the mating types + and - exist in 1:1 ratio, most patient isolates are mating type -. This reasons for increased representation of (-) mating types in clinical specimens is unknown. Microscopic evaluation of the mycelial phase reveals two types of conidia. Macroconidia are 8 micrometers to 15 micrometers in diameter while microconidia are 2 micrometers to 5 micrometers. Microconidia are believed to be the infective particles and are small enough to be lodged in the alveoli when inhaled.

H. capsulatum has five to seven chromosomes. Recently, molecular techniques have identified eight clades of H. capsulatum, which are distributed in different parts of the world. There are two North American clades, two South American clades, one Australian, one Indonesian, one African, and one Eurasian clade. The genetic differences have clinical implications as North American clades do not cause primary skin disease while South American clades do. The African clade includes all of H. capsulatum variety duboisii.

Once microconidia are lodged in the alveoli, these particles undergo a transformation in response to body temperature resulting in unicellular yeast forms typically 2 micrometers to 5 micrometers in diameter. Genes essential for transition and growth of yeast cells have been identified and are Ryp1, Ryp2, and Ryp. Conidia within the alveoli bind to the CD11-CD18 family of integrins and are engulfed by neutrophils and macrophages. It is, therefore, possible that the phase transformation from conidia to yeast is intracellular. The duration of the phase transition ranges from hours to days. The yeast phase is responsible for the infectivity of the fungus. This yeast reproduces by narrow-based and sometimes multipolar budding.

Epidemiology

Histoplasmosis is the most common endemic mycosis in the United States. It is not a reportable disease. The presumed geographic distribution and endemicity are the Midwest and Southeastern regions of the United States. This information is largely derived from skin test surveys performed during the 1940s. Between 1938 through 2013 over 100 outbreaks involving approximately 3000 cases have been reported in 26 states and the territory of Puerto Rico. In the above publication, an outbreak was defined as two or more cases. Common exposure settings were chicken coops or construction projects. Birds, bats, or their droppings were reported to be present in 77% of the outbreak settings, and workplace exposures were reported in half of the outbreaks. In endemic regions and sporadic cases, the exact exposure is difficult to pinpoint, as frequently symptoms are due to reactivation of the disease.

Worldwide there are pockets of endemicity on each continent. Published cases have been reported from Italy in Europe, from North, Central and South America, West Africa (Congo and Zimbabwe), South Africa, Southeast Asia (India, China, Malaysia, Taiwan), and Australia. More than half the world’s population potentially lives in the endemic region of H. capsulatum.

History and Physical

Acute Pulmonary Histoplasmosis

Patients may be asymptomatic and show evidence of granulomatous disease on chest x-ray. Lungs are the entry point for the infective particles or conidia to enter the host. The tissue response to the invasion results in granulomas. These granulomas can be caseating or noncaseating granulomas in which calcium may be deposited. The function of the granulomas is to contain fungal growth. Organized granulomatous inflammation is typically observed in the self-limited disease. The lack of an organized inflammatory response is indicative of a perturbed cellular immune response, in which case the patient develops progressive disseminated Histoplasmosis. Formation of the granulomas requires the generation of IFN-gamma, TNF-alpha, and IL-17.

The X-linked hyper-immunoglobulin M syndrome is associated with defective IL-17 generation, and the majority of these individuals develop disseminated histoplasmosis.

Primary infections are frequently asymptomatic, or the patients tend to ignore mild flu-like symptoms. The major determinant of symptoms is the inoculum size. The typical incubation period is seven to 21 days. High fever, headache, nonproductive cough, and chest pain are the main symptoms. This chest pain is not pleuritic and is in the anterior chest and is believed to be due to enlargement of mediastinal or hilar lymph nodes. Most of the symptoms resolve in 10 days. Rheumatologic manifestations can occur such as arthralgias, erythema nodosum or erythema multiforme in a small number of patients (6%, mostly women). This syndrome appears to be less frequent in histoplasmosis when compared to coccidioidomycosis. Imaging shows patchy diffuse pneumonitis and hilar lymphadenopathy. There is no granulomatous inflammation as cellular immunity matures by two weeks in primary infection. During the acute pulmonary infections, a skin test may be positive in more than 90% of cases, antibody to H. capsulatum may be present in 25% to 85% of cases, the urinary antigen may be positive in 20% of cases, and sputum culture from lungs may be positive in less than 25% of cases.

During primary infection, about 6% of patients develop acute pericarditis. The likely cause of the pericarditis is the granulomatous inflammatory response that is mounted in mediastinal lymph nodes adjacent to the pericardium. However, the case of acute pericarditis due to direct Histoplasma capsulatum infection leading to granulomatous inflammation within the pericardial sac has been reported.

Patients living in the endemic area may have recurrent exposures to the H. capsulatum. The onset of illness is sooner, within three days and the duration of the illness is brief in repeat exposures. The characteristic chest radiograph in cases of multiple recurrent acute infections is one of the numerous small nodules that are diffusely scattered throughout both lung fields. This feature has been referred to as miliary granulomatosis; hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy is absent.

Sometimes due to the presence of the yeast, the initial granuloma may continue to grow in layers of inflammatory cells are deposited concentrically in an attempt to control the yeast. There is active inflammation in the periphery, and the central core may have calcification giving the appearance of malignancy. Frequently, a biopsy is done for these pulmonary masses to exclude malignancy and yeast are often detected incidentally. Patients are then referred to infectious disease physicians for therapy, who treat for three months similar to an uncontrolled acute infection. The rationale is that after the biopsy, the yeast is no longer contained anatomically and now have access to the pulmonary parenchyma to cause progressive disease.

During the healing process, the enlarged mediastinal nodes adherent to mediastinal can cause retraction of the airways, leading to post-obstructive pneumonia, hypoxemia, and bronchiectasis. This is rare but is seen in endemic regions. There is no need to treat this complication of acute histoplasmosis due to fibrosis.

Chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis

Chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis can present as cavitary or noncavitary disease. During the initial descriptions of the disease from epidemics in Indianapolis, it seemed that male smokers with the underlying severe chronic obstructive disease were most likely to have cavities. Recent evaluation has shown that to be not true. Fifty percent of women with Chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis can have had cavities, and only 20% patients had a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Overall, cavities occurred in 40% of patients with chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis. Most of the cavities were located in upper lobes, and the sputum cultures were positive. During the chronic pulmonary infections, a skin test may be positive in 70-90% of cases, antibody to H. capsulatum may be present in 75% to 95% of cases, the urinary antigen may be positive in 40% of cases and culture from lungs may be positive in 5% to 70% of cases. Sputum or bronchioalveolar lavage cultures are highly unlikely to be positive in the noncavitary form of the disease (5%). On imaging, the noncavitary form of chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis shows nodules, infiltrates, mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The disease is contained, but the tissues are not cleared of the yeast, in the noncavitary form of the chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis. Therefore, treatment is indicated.

Following healing, recurrence of cavitary lesions may occur in 20% of patients, which needs to be treated again; prognosis does not change with this relapse. The response rate to therapy is better in the noncavitary form of chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis when compared to the cavitary form. Overall there is relapse rate of 15% to 20%. Death is highly unlikely from chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis but is often due to pulmonary comorbidities.

Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis

From the pathogenesis perspective, all infections with histoplasmosis become disseminated as the macrophages are constantly trafficking between the lungs and other organs. Therefore the qualifier “progressive” is applied and refers to the uncontrolled growth of the organism in multiple organ systems. These patients present with fever, weight loss, hepatosplenomegaly and hematologic disturbances. During progressive disseminated histoplasmosis, a skin test may be positive in 3% to 55% of cases, antibody to H. capsulatum may be present in 70% to 90% of cases, the urinary antigen may be positive in 70% to 90% of cases and culture from lungs may be positive in 50% to 70% of cases.

Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis can also be classified as acute, sub-acute or chronic. This classification is based on the symptomatology. If the acute pulmonary infection becomes protracted and progresses to disseminated disease, it is considered acute progressive disseminated histoplasmosis. In the past, this was referred to as infantile form because these patients had an initial primary infection. In the subacute and chronic forms, however, the symptoms are protracted and is unclear if the disease is due to primary infection or reactivation.

Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis can be mild, moderate or severe based on the acuity and gravity of the symptoms. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis is seen in patients who have an immunocompromised state. Severe cases have complications such as hemophagohistiocytosis. If untreated, progressive disseminated histoplasmosis is 100% fatal.

Evaluation

History of exposure could be difficult to pinpoint in sporadic cases in an endemic region. Cleaning basements, house attics, construction work, working with soil are some of the exposures. Pulmonary symptoms may be mild to severe. Some patients can present with fever of unknown origin and weight loss. Night sweats may be present. Patients may be diagnosed with pneumonia, have multiple cavitary lesions in the lungs.[5][8][9][10]

Laboratory Evaluation

The workup includes serological tests such as complement fixation, immunodiffusion and enzyme immunoassays. It is important to send the serological tests for Blastomyces dermatitides and coccidioidomycosis as well since the endemic regions overlap in some places. Imaging may show healed granulomas in the lungs, spleen or liver. It is important to obtain complete blood count (CBC) to look for any bone marrow suppression. A bronchoscopic alveolar lavage (BAL) culture is unlikely to be positive but can be done to exclude other concomitant pathology. A BAL is sometimes positive particularly when there are cavitary lesions or if there were macroconidia that got deposited in the proximal airways.

Antibody tests are useful for diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis but not in all cases. The two standard assays are complement fixation and immunodiffusion assay. Complement-fixing antibodies may appear three to six weeks (sometimes as early as two weeks) following infection by H. capsulatum in 95% of the patients. Complement fixation antibodies persist for years after infection. A single high titer of 1:32 or a fourfold rise in titer is used to diagnose acute infection. Complement fixation antibody is less specific than immunodiffusion assay, which tests for the presence of M and H precipitin bands. (the sensitivity and specificity is in mid-sixties). The antigen extract of the Histoplasma mycelial form is histoplasmin. The antibodies to histoplasmin are C, H, and M. The C antigen is a carbohydrate (galactomannan) that is largely responsible for the cross-reactions observed with other fungal species. An M band develops with acute infection, persists for months to years and is also present in chronic forms. H band appears after M band and may disappear early. Thus, H band is almost always present with M band, and the presence of both M and H band suggests active histoplasmosis. The specificity range is in the 80s, but the sensitivity is similar to complement fixation.

Latex agglutination tests have been developed which do better than complement fixation and immunodiffusion but can have false positives and cannot differentiate B. dermatitis infection.

Western blot and enzyme immune assays have been developed for the diagnosis of histoplasmosis. There are several ELISA protocols. An ELISA using a yeast cell extract showed a sensitivity of 86% in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis and a specificity of 91% using anti-human IgG, whereas with anti-human IgM the sensitivity was 66% and the specificity 100%. Different labs have specific protocols as well.

Detection of antigen may be more effective and useful in acute disease as well as in patients who are immunocompromised and do not have good antibody response. In general, patients with disseminated histoplasmosis have high levels of Histoplasma antigenuria, and the level is used for diagnosis and for following response to therapy. Decreasing level of antigen titers is directly correlated with improvement of the patient’s clinical condition. False-positive Histoplasma antigen detection tests can occur in patients with blastomycosis or paracoccidioidomycosis. Urinary antigen detection is more sensitive than serum antigen detection (95% versus 86% in one study). At times the lab reports low positive urinary antigen. In one study 52% of the cases were true positive, and 48% of cases was a false positive. Of the 12 false positive cases, three had blastomycosis, two had coccidioidomycosis, two had sarcoidosis, in three, etiology was unclear, and two had a bacterial infection. In an immunosuppressed patient, a low urinary antigen is likely to be a true positive.

Differential Diagnosis

Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis: causes of atypical pneumonia.

Chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis: tuberculosis, mycobacterial, blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, and sarcoidosis.

Histoplasma can be misidentified in the microbiology laboratory due to confusion with the following organisms: Candida glabrata, Penicillium marneffei, Pneumocystis (carinii) jiroveci, Toxoplasma gondii, Leishmania donovani and Cryptococcus neoformans.

Treatment / Management

In 2007, the Infectious Disease Society (IDSA) published guidelines for treatment of histoplasmosis. Acute pulmonary infections, with symptoms less than four weeks do not need treatment. If the symptoms persist beyond this period, a three-month course of itraconazole is recommended. In patients with CPH, noncavitary disease, a six-month therapy will suffice, whereas cavitary disease may have to be treated for a year. Patients with PDH, generally require induction therapy with amphotericin-B for two to four weeks followed by a year of itraconazole. There is evidence showing that the liposomal amphotericin B has better outcomes compared to other preparations of amphotericin B. Currently, no other antifungal agent has been recommended by IDSA, however, there are reports of patients being treated with posaconazole, as salvage therapy, in the maintenance phase instead of itraconazole and the inductive phase instead of amphotericin B.[11][12][13][14]

Differential Diagnosis

- Aspiration pneumonitis and pneumonia

- Coccidioidomycosis and valley fever

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of patients with histoplasmosis is best done by an interprofessional team that includes a thoracic surgeon, pulmonologist, pathologist, laboratory specialist, nurse practitioner and an infectious disease expert. In general, asymptomatic patients do not need treatment, but all symptomatic patients need treatment. Close follow up is required as histoplasmosis can in rare patient induce mediastinal fibrosis and fistula formation. The duration of treatment has not been defined but consensus is that until all symptoms subside.

For healthy people, the outcomes are good but histoplasmosis in immunosuppressed patients has high morbidity and mortality.[15][3][16]