Continuing Education Activity

Sexual assault is a traumatic experience that can expose survivors to the risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Preventing these infections is essential as they can lead to long-term complications. The prevalence of STIs after sexual assault varies, with higher rates for some infections like trichomoniasis and bacterial vaginosis. While routine testing for STIs may not be performed in many cases, prophylactic treatment is often recommended. This includes antibiotics for chlamydia, gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis, as well as preventive measures for hepatitis B, HPV, and HIV. Follow-up care is crucial but often faces challenges, with factors influencing compliance. A multidisciplinary healthcare team collaborates to provide comprehensive care to survivors, addressing physical, psychological, and legal aspects. This activity covers the interprofessional approach to evaluation, treatment, and follow-up and aims to minimize the risk of STIs and support survivors on their path to recovery.

Objectives:

Apply the CDC's current guidelines for prophylaxis of sexually transmitted bacterial infections.

Screen survivors of sexual assault for potential sexually transmitted infection exposure, utilizing appropriate diagnostic tests and considering the individual's risk factors.

Implement evidence-based prophylactic treatments for sexually transmitted infections, ensuring timely administration and considering the survivor's medical history and vaccination status.

Communicate effectively with the interprofessional healthcare team, including physicians, advanced practice clinicians, nurses, forensic experts, social workers, and counselors, to ensure comprehensive care for survivors.

Introduction

Sexual assault is any sexual act performed by one person on another without seeking consent. The assault may result from the threat of force, force, or from the victim's inability or refusal to give consent. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are feared sequelae of sexual assault. The most common STIs diagnosed in female survivors of sexual assault are chlamydia, gonorrhea, bacterial vaginosis, and trichomoniasis.[1]

Prevention is paramount as survivors who contract infections risk enduring long-term complications, including pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, and even certain types of cancer. Recommendations for appropriate management after a sexual assault have changed several times over the last decade. The treatment of STIs following sexual assault exhibits variability between countries and within the same country. Local factors such as antibiotic resistance patterns and prevalent infections in the region often influence these differences.

The prevalence of infection and antibiotic susceptibility are dynamic and subject to ongoing changes; new sexually acquired infections can emerge, exemplified by the advent of HIV in the 1980s.

Over the past half-century, significant advancements have been made in developing effective medications to combat various STIs, including HIV. The information provided adheres to the current guidelines established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO).

Issues of Concern

Incidence and Prevalence

The transmission of STIs after sexual assault varies widely among populations. These rates encompass a broad spectrum, with higher reported prevalence reaching 12% for trichomoniasis and 19% for bacterial vaginosis, while estimates are relatively lower for chlamydia (2%) and gonorrhea (4%). Due to methodological issues, some of these positive cultures may reflect preexisting infections.

The literature does not offer dependable estimate data regarding the risk of transmitting herpes, hepatitis B, or HIV infection through sexual assault. However, it is essential to note that sexual transmission of hepatitis B is prevalent, even in the United States, particularly among nonvaccinated individuals who engage in receptive intercourse with partners who are hepatitis B-positive. Hepatitis B and HIV transmission following sexual assault have been documented.[2]

The incidence and prevalence of all STIs in the local area must be considered when determining the most appropriate treatment for a patient. STIs are common in the United States, particularly among those aged 15 to 24. The lifetime prevalence of sexual assault in the United States is approximately 2% to 3% in men and 18 to 19% in women.[3] Human papillomavirus has the most significant incidence and prevalence of any STI in the United States.[4]

Testing

The CDC recommends selective testing for STIs when individuals present for evaluation after sexual assault. In the United States, most advanced practitioner Sexual Assault Response Teams do not routinely perform STI testing on adults and adolescents. This is because STI specimen collection during a sexual assault examination frequently detects infections acquired before the assault rather than those transmitted by the perpetrator, making it less relevant for the criminal investigation.

Child victims may be an exception to this practice if they exhibit signs or symptoms of an STI. If authorities suspect ongoing child sexual abuse, discovering an STI may provide laboratory evidence of the abuse.

For the vast majority of adults and adolescents, routine prophylactic antibiotic treatment against Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and incubating syphilis renders testing and discovery of preexisting infections costly as management does not usually differ.[1]

Clinical Significance

Recommended Treatment

Recommended screening for infectious disease begins with a history and physical. Providers should aim to determine an appropriate treatment while minimizing the possibility of retraumatizing the patient. All decisions are made on a case-by-case basis. Because compliance with follow-up is low, the CDC recommends antibiotics for chlamydia, gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis (see Tables 1 and 2), as well as emergency contraception, hepatitis B, HPV, and HIV evaluation.[5] Patients should also be counseled on symptoms of STIs to help them determine if they require further evaluation at a later time.

Table 1. CDC's Recommended Regimen for Adolescent and Adult Female Sexual Assault Survivors

| Ceftriaxone 500 mg IM in a single dose. For persons weighing ≥150 kg, 1 g of ceftriaxone should be administered. |

| PLUS |

| Doxycycline 100 mg 2 times/day orally for 7 days. |

| PLUS |

| Metronidazole 500 mg orally 2 times/day orally for 7 days |

Table 2. CDC's Recommended Regimen for Adolescent and Adult Male Sexual Assault Survivors

|

Ceftriaxone 500 mg IM in a single dose. For persons weighing ≥150 kg, 1 g of ceftriaxone should be administered.

|

| PLUS |

| Doxycycline 100 mg 2 times/day orally for 7 days |

(CDC, STI Treatment Guidelines, 2021)

Bacterial Infections

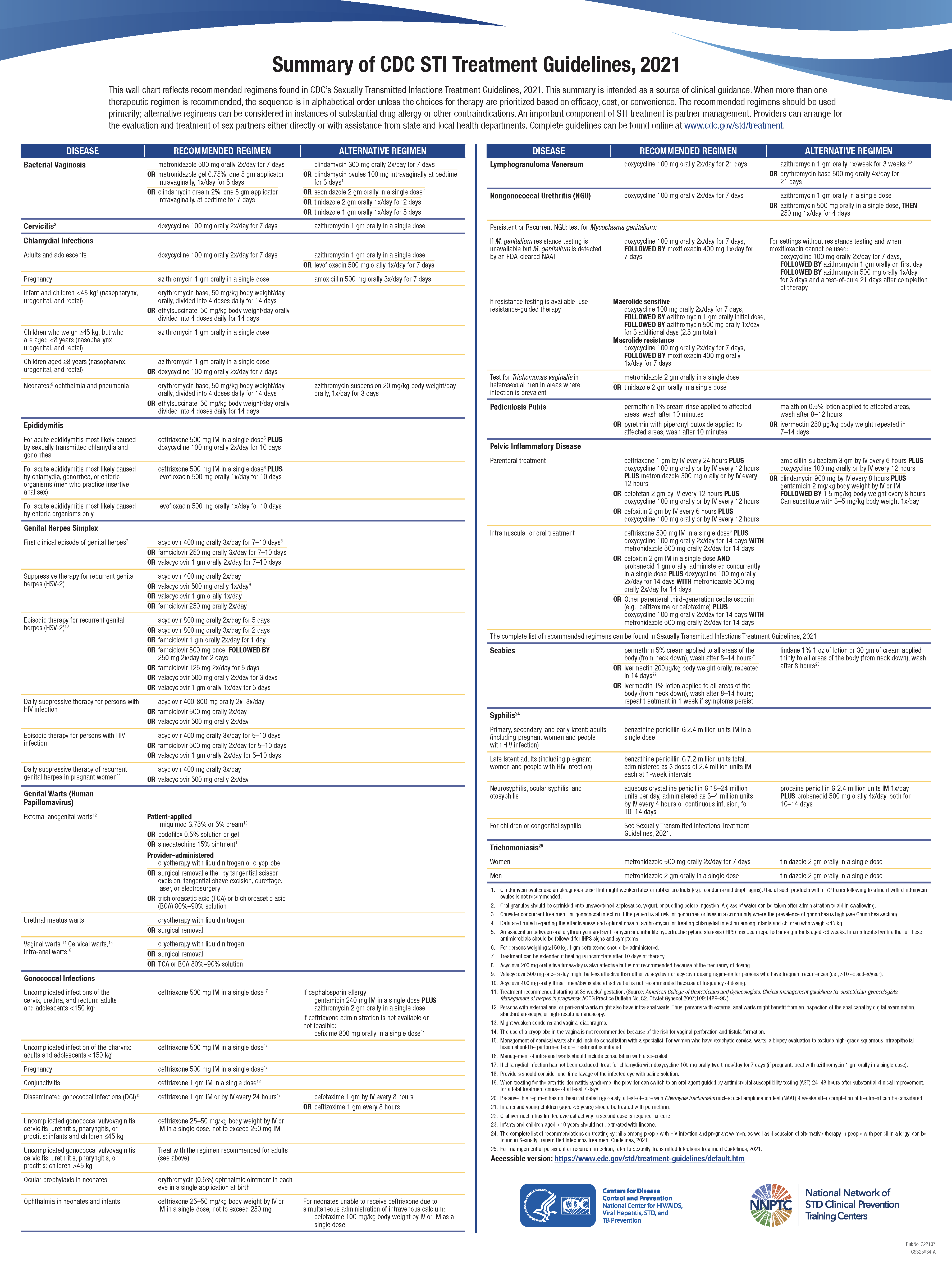

See the chart that reflects recommended regimens found in CDC’s Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021 (Image. CDC STI Treatment Summary).

Chlamydia and gonorrhea

Standard recommendations include the treatment of gonorrhea and chlamydia at the time of the initial examination. Though "prophylaxis" is the term used for the antibiotic administration for gonorrhea and chlamydia, it is more appropriately considered treatment because the infection has yet to produce clinical symptoms, assuming the perpetrator transmitted the bacteria to the victim. The suggested evaluation includes nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) for C trachomatis and N gonorrhea at penetration sites.

Gonorrhea: Currently, the CDC recommends ceftriaxone in a 500 mg dose intramuscularly (IM) as the drug of choice for preventing active infection of gonorrhea after sexual assault. Ceftriaxone in this dose also effectively prevents incubating syphilis from becoming clinical.

Chlamydia: For chlamydia prophylaxis, oral doxycycline is now the first-line recommended treatment administered at 100 mg orally twice a day for 7 days. Alternate options include azithromycin 1 gram orally in a single dose or levofloxacin 500 mg once daily for 7 days. Azithromycin was previously favored over doxycycline, but doxycycline is now considered superior due to better microbial efficacy, especially for rectal and possibly pharyngeal infections.[6] Adverse effects are mainly similar to both antibiotics and include nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and dyspepsia.[7]

Pelvic inflammatory disease: The recommended outpatient regimen is ceftriaxone 500 mg intramuscularly in a single dose, plus doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 14 days, plus metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily for 14 days.

Bacterial vaginosis

Increased suspicion of this condition occurs when the patient presents with malodorous discharge or vaginal itching. The suggested evaluation includes vaginal pH measurement, wet mount, and Whiff test.

Syphilis

No specific recommendation for prophylactic treatment for syphilis is available; instead, a serum sample should be evaluated. Prophylactic therapy for gonorrhea may prevent incubating syphilis from becoming clinical.

Viral Infections

Hepatitis B

The CDC recommends serologic testing for hepatitis B in cases where the victim's vaccination status is uncertain. In certain situations, examiners may opt to refer patients for HIV and hepatitis B testing later, as the immediate communication of positive test results and the facilitation of treatment may prove impractical. Testing for hepatitis B is advised because vaccination and immune globulin treatment may not always be effective. Moreover, if the virus is transmitted during the assault, victims may become eligible for lifetime coverage of medical expenses related to viral transmission through the Crime Victim's Compensation Program.

Testing may be omitted in cases where the victim is confirmed to be adequately vaccinated, exhibits an appropriate antigenic response, and does not require postexposure prophylaxis.

In victims known to be unvaccinated, administer vaccination contemporaneously with an examination or within 24 hours of the assault. Schedule the following vaccines in this series for 1 to 2 months and 4 to 6 months after the first dose for series completion. When the victim is uncertain of hepatitis B vaccine administration, the clinician should treat the patient as if unvaccinated.

When confirmed that the perpetrator is hepatitis B antigen-positive and the victim is unvaccinated with a negative hepatitis B antibody test result, the CDC recommends administering hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) along with simultaneous vaccination at a different site, ideally within 24 hours of exposure.

HPV

The CDC recommends HPV vaccination for sexual assault survivors, particularly those younger than 26, including females aged 9 to 26 and males aged 9 to 21 who have not received prior vaccination or those who have only received partial immunization. These include female patients aged 9 to 26 and male patients aged 9 to 21. Men who have sex with men (MSM) not previously vaccinated or incompletely vaccinated may also receive the HPV vaccine before age 26. The HPV vaccination series typically consists of 3 doses. The second vaccine is administered 1 to 2 months after the first dose, and the third dose is administered 6 months after the first.

Prevention of HIV Infection

While there are no published studies specifically addressing the effectiveness of HIV postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) after sexual assault, it is worth noting that PEP for parenteral occupational exposure to infected body fluids, such as needlestick injuries, is believed to be effective based on case-control studies.

The risk of HIV transmission from a single instance of unprotected consensual receptive vaginal intercourse with an infected individual is estimated to be approximately 1 to 2 in 1000. However, in cases of sexual assault, the violent nature of the assault and resulting injuries may increase the transmission rate. After unprotected receptive anal intercourse, the transmission risk has been reported to be higher, ranging from 5 to 32 per 1000 incidents.[8]

A significant proportion of sexual assault victims, nearly half, have concerns about the risk of acquiring HIV following the assault. Examiners need to acknowledge and address these concerns, offer counseling, and make arrangements for initiating antiretroviral medications, referred to as postexposure prophylaxis or PEP, as they can effectively prevent HIV transmission. In the rare circumstance where rapid HIV testing of the perpetrator can be conducted concurrently with the victim's examination, this information can be utilized to guide PEP, similar to the approach used for occupational exposures. However, this is an unlikely scenario.

The CDC recommends initiating postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) for sexual assault victims within 72 hours of an assault, particularly when there is a significant risk of transmission and the perpetrator is known to be HIV-positive.[9] As with occupational exposure, PEP should be initiated as soon as possible after the assault. HIV seroconversion due to failures of PEP following sexual exposure has been reported. In situations where the HIV status of the perpetrator is unknown, the CDC recommends that practitioners make decisions regarding PEP on a case-by-case basis in consultation with the patients

Some states in the United States legislate medical examiners to offer HIV PEP to all sexual assault victims, and practitioners must be aware of their state laws. The CDC guidelines provide a useful framework to approach individual decisions in prescribing HIV PEP. PEP decisions can be assisted by calling the National HIV Telephone Consultation Service (800-933-3413 or 888-448-4911) or accessing the National HIV/AIDS Clinician's Consultation Center online.[8][10]

Postexposure prophylaxis for HIV

Several possible regimens for PEP are used. The preferred regimen is tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine, plus one of the following: raltegravir, 400 mg twice daily, or dolutegravir, 50 mg once daily.

Alternate regimes include the following:

- Rilpivirine-emtricitabine-tenofovir disoproxil fumarate tablet

- Elvitegravir-cobicistat-emtricitabine-tenofovir disoproxil fumarate tablet

- Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-emtricitabine tablet plus a pharmacologically boosted protease inhibitor

Dolutegravir can potentially cause neural tube defects, so it should be avoided in women of reproductive potential. Additionally, regimens containing cobicistat may result in decreased drug levels during pregnancy. Therefore, these regimens should not be used in individuals of childbearing potential who are planning to become pregnant.

Parasitic Infections

Trichomoniasis

While the CDC recommends routine medication administration to prevent symptomatic trichomoniasis infection, some clinicians may hesitate to prescribe this treatment due to the significant adverse effects associated with the recommended antiprotozoal agents. As an alternative, examiners may offer prophylaxis for trichomoniasis with a single 2-gram oral dose of metronidazole or tinidazole, as per CDC recommendations.

Metronidazole can often induce nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, which may interfere with the absorption of other antibiotic prophylaxis and emergency contraception. Therefore, if examiners opt to provide this treatment, it is advisable to give the patient metronidazole to take at home several hours after the other medications have been administered and absorbed.[1]

Other Issues

Follow-Up and Medication Compliance

Follow-up rates in sexual assault survivors have historically been between 10% and 31%. While a minority of victims may follow through with the recommended follow-up medical care, offering and discussing this option with victims verbally and emphasizing its importance through clear written instructions remains crucial. The consensus is to recommend follow-up within 1 to 2 weeks for repeat STI testing if the initial examination did not provide complete treatment. Additionally, follow-up at 4 to 6 weeks and 3 to 6 months is advised for HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and syphilis serology testing.[11]

When a nurse coordinator is tasked with contacting patients to coordinate a follow-up appointment, the follow-up rates are reported to be significantly higher (85%).[12] Factors that positively influence follow-up compliance include younger age, alcohol consumption during the assault, the presence of genital trauma, and receiving prophylactic medications. Conversely, factors associated with decreased follow-up rates include homelessness, experiencing intimate partner violence, cocaine use, and psychiatric comorbidity.[5]

Adherence to PEP is lower for victims of sexual assault than other exposures, highlighting a need for increased attention and guidelines concerning treating sexual assault survivors.[10] Factors that increased compliance with follow-up care included encouragement from healthcare providers and peers to take PEP, the knowledge of the perpetrator's HIV-positive status, financial support for transportation, counseling session participation, and HIV testing and PEP offered during the initial consultation.[13]

Guidelines

CDC guidelines for evaluating and treating sexual assault victims are limited to female and pediatric patients; a few of the guidelines apply to male victims.[11] Further, many of the studies regarding postexamination follow-up focus on the factors affecting female survivors. Limited research focuses on male and LGBT survivors and aspects affecting their follow-up.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

In sexual assault infectious disease prophylaxis, the interprofessional healthcare team collaborates closely to provide comprehensive care to survivors. This collaborative effort involves professionals from various disciplines, including emergency medicine physicians, nurses, sexual assault nurse examiners, forensic experts, infectious disease specialists, social workers, and counselors.

First and foremost, emergency medicine physicians and sexual assault nurse examiners work together to evaluate the survivor's physical and psychological well-being thoroughly. They perform examinations, collect forensic evidence, and provide initial support. Forensic experts play a critical role in preserving evidence for potential legal proceedings and collaborate closely with law enforcement to ensure the proper handling of evidence.

Infectious disease specialists are essential in assessing the risk of STIs to determine the most appropriate medications for PEP based on the specific circumstances of the assault.

Nurses are pivotal in administering medications, educating survivors about PEP, and monitoring for potential adverse effects. Meanwhile, counselors provide much-needed emotional support and trauma-informed care, addressing the survivor's mental health needs during a difficult time.

Social workers within the team help coordinate follow-up care, including scheduling appointments for repeat testing and counseling. They may also assist survivors in accessing resources such as support groups and legal services.

Effective communication among team members is fundamental, ensuring that all aspects of care are addressed comprehensively. Accurate and detailed documentation is crucial for legal purposes and continuity of care.

The team collaborates to ensure that survivors receive appropriate follow-up care, including repeat testing for STIs and ongoing counseling. This may involve scheduling appointments and providing transportation support when necessary.

Throughout the entire process, the healthcare team places the survivor's well-being and choices at the center of care, obtaining informed consent for all medical procedures and treatments. Collaboration with law enforcement and legal professionals is vital for addressing potential criminal charges against perpetrators and ensuring that survivors are supported throughout legal proceedings.

In summary, interprofessional collaboration is paramount in sexual assault infectious disease prophylaxis, enabling the delivery of comprehensive and patient-centered care that considers survivors' physical and psychological needs while addressing legal aspects as well. This multidisciplinary approach aims to minimize the risk of STIs and provide crucial support to survivors on their path to recovery.