Continuing Education Activity

Ulnar nerve palsy is the loss of sensory and motor function. This can occur after injury to any portion of the ulnar nerve. The ulnar nerve is the terminal branch of the medial cord (C8, T1). The ulnar nerve innervates the flexor carpi ulnaris and the flexor digitorum profundus after it passes through the cubital tunnel. When the ulnar nerve is injured, the muscles innervated by the nerve begin to weaken. This leads to an imbalance between the strong extrinsic muscles (i.e., extensor digitorum communis) and the weakened intrinsic muscles (i.e., interosseous and lumbrical). This imbalance is characterized clinically by metacarpophalangeal (MCP) hyperextension and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and distal interphalangeal (DIP) flexion. This activity describes the pathophysiology, evaluation, and management of ulnar nerve palsy and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the management of this condition.

Objectives:

- List the precipitating conditions that can bring about ulnar nerve palsy.

- Describe the examination and evaluation necessary to accurately diagnose ulnar nerve palsy.

- Review the treatment options for ulnar nerve palsy, based on the specific etiology.

- Explain interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance the recognition and management of ulnar nerve palsy and improve outcomes.

Introduction

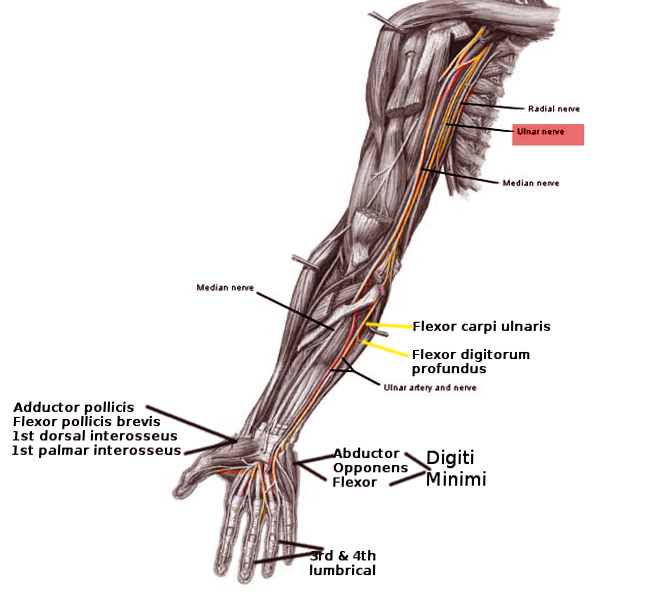

Ulnar nerve palsy can result in loss of sensory and motor function. This can occur after injury to any portion of the ulnar nerve. The ulnar nerve is the terminal branch of the medial cord (C8, T1). The ulnar nerve innervates the flexor carpi ulnaris and the flexor digitorum profundus after it passes through the cubital tunnel.[1][2][3][4]

The nerve provides sensation over the medial half of the 4th finger and the entire 5th finger, and the ulnar portion of the dorsal aspect of the hand.

Muscles innervated by the ulnar nerve include:

- Abductor digiti minimi

- Flexor digitorum profundus

- Flexor digiti minimi

- Opponens digiti minimi

- Ring finger lumbricals

- Small finger lumbricals

- Dorsal and palmar interosseous muscles

- Adductor pollicis

- Deep head of flexor pollicis brevis

When the ulnar nerve is injured, the muscles innervated by the nerve begin to weaken. This leads to an imbalance between the strong extrinsic muscles (i.e., extensor digitorum communis) and the weakened intrinsic muscles (i.e., interossei and lumbricals). This imbalance is characterized clinically by metacarpophalangeal (MCP) hyperextension and proximal interphalangeal (PIP), and distal interphalangeal (DIP) flexion. After carpal tunnel syndrome, entrapment of the ulnar nerve is the second most common neuropathy of the upper extremity.

The ulnar nerve can be entrapped at several sites. The cubital tunnel is the most common. The other sites are the medial intermuscular septum, the ulnar groove in the epicondylar region, and the deep flexor pronator aponeurosis. Entrapment in Guyon's canal results in ulnar tunnel syndrome.

Etiology

Anything that may lead to ulnar nerve palsy can cause claw hand. Ulnar nerve palsy can arise from a laceration anywhere along its course. Proximal injuries to the medial cord of the brachial plexus may also present with sensory loss distally. Ulnar nerve palsies can also be due to cubital tunnel syndrome and ulnar tunnel syndrome. These are compression neuropathies at the elbow and wrist. Another cause of ulnar nerve palsy may be a failure to splint the hand in an intrinsic-plus posture following a crush injury. There are a few systemic diseases that may also lead to ulnar nerve palsy. These include leprosy, syringomyelia, and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. However, these systemic diseases usually involve more than one nerve.[5][6]

When a claw hand results, it is usually due to paralysis of the lumbricals.

Epidemiology

Claw hand can be congenital or acquired. Men are more likely to acquire the condition than women, but the congenital form of claw hand is distributed evenly among both sexes. There are no racial or ethnic preferences for claw hand.

Pathophysiology

Pathoanatomic components relate to the imbalance between the extrinsic and intrinsic muscles. Weakened intrinsic muscles lead to a loss of MCP flexion and a loss of interphalangeal (IP) extension. Strong extrinsic muscles will lead to an unopposed extension of the MCP joints. The flexor digitorum profundus and flexor digitorum superficialis muscles not innervated by the ulnar nerve remain strong and lead to unopposed flexion of the PIP and DIP joints.

History and Physical

The initial presentation will include a decrease in normal hand function.

The MCP joints will be hyperextended, and the IP joints flexed.

The second and third digits will not be as involved as the fourth and fifth digits with a true ulnar nerve palsy. This is because the median nerve innervates the lumbricals involving the second and third digits, and the ulnar nerve innervates the lumbricals involving the fourth and fifth digits.

The patient may also exhibit functional weakness while attempting a grasp, grip, or pinch.

A provocative test for claw hand is bringing the MCP joints into flexion. This will correct the DIP and PIP joint deformities.

Several other specific tests for ulnar nerve palsy include:

- Froment sign: Hyperflexion of the thumb IP joint while attempting to pinch. This indicates a substitution of flexor pollicis longus (innervated by median nerve) for adductor pollicis (innervated by ulnar nerve).

- Jeanne sign: Reciprocal hyperextension of the thumb MCP joint indicating substitution of flexor pollicis longus (FPL) for adductor pollicis.

- Wartenberg sign: Abduction of the small finger at MCP joint indicating deficient palmar intrinsic muscle (innervated by ulnar nerve) with abduction from extensor digiti minimi (innervated by the radial nerve).

- Duchenne sign: Clawing of the ring and small fingers, hyperextension of MCP joints, and flexion of PIP joints indicating deficient interosseous and lumbrical muscles of the ring and small fingers.

Evaluation

Electromyographic and nerve conduction velocity studies are used to evaluate the ulnar nerve pathology and to rule out other diagnoses.[7][8]

Treatment / Management

Nonoperative management is applied if a fixed flexion contracture of more than 45 degrees occurs at the PIP joint. A strenuous hand therapy program is utilized involving serial casting.[9][10]

Exercises that strengthen the interosseous muscles and lumbricals are recommended. The individual should be taught to exercise each finger and thumb in abduction and adduction motion while the hand is pronated. In addition, the MCP and ICP joints should be exercised, and over time the interosseous and lumbricals will gain strength.

The majority of cases will need operative management in the form of contracture release and passive tenodesis versus active tendon transfer. This treatment is reserved for those patients with a progressive deformity that is affecting their quality of life. The goal is to prevent lasting MCP joint hyperextension.

- Surgery is usually in the form of tendon transfers. This addresses issues including the lack of thumb adduction and lateral pinch, the claw deformity of the fingers that impairs object acquisition, and the loss of ring and small finger flexion.

- The extensor carpi radialis brevis or the flexor digitorum superficialis is the most commonly used transfers to restore thumb adduction. The brachioradialis can be used if the extensor carpi radialis brevis is required for an intrinsic reconstruction of the fingers.

- To correct the claw deformity of the fingers, include static procedures or dynamic transfers. A dynamic transfer uses the flexor digitorum superficialis, extensor carpi radialis longus, extensor carpi radialis brevis, or flexor carpi radialis as a donor muscle.

- To restore the ring and small finger extrinsic muscle function, a transfer of flexor digitorum profundus ring and small to flexor digitorum profundus middle is performed.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of a claw hand should include:

- Cervical radiculopathy

- Dupuytren contracture

- Klumpke paralysis

- Lower brachial plexopathy.

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on the type and extent of nerve injury. For mild nerve injury, recovery is possible, but if the nerve was transected, recovery is rare. Even those who recover may require prolonged hand rehabilitation and may never regain full strength of the hand muscles. Poor prognostic factors include:

- Advanced age

- Coexisting diabetes

- Absent sensory response

- Muscle atrophy

Some studies do not show much improvement even after transposition of the ulnar nerve.

Complications

- More complications occur after intrinsic tendon transfers than adductor-plasty because of the unique balance of the extensor hood mechanism.

- The transfer may not be suitable if the chosen muscle has insufficient strength or excursion. Elongation is also a problem with sewing the transfer into the lateral bands of the extensor hood.

- Tendon transfers that are not strong enough can be treated with a therapy program to strengthen the muscle but often require surgical revision.

- The transfer may also not be suitable if the chosen muscle has too much strength or too short of the excursion. When the transfer is sewn too tightly into the lateral band, it can produce a swan-neck deformity of the digit.

- Tendon transfers that are too tight or too strong can be treated with a passive range of motion therapy to allow stretching to occur.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

A very experienced hand therapist plays a vital role in the postoperative care of tendon transfers for ulnar nerve palsy. Protecting the transfers with custom splints while mobilizing uninvolved joints requires strict adherence to postoperative protocols. Following most procedures, the hand is immobilized for 3 to 4 weeks, followed by a blocking splint to allow movement within the restraints of the splint for the next 3 to 4 weeks. Passive exercises are started at 6 weeks and strengthening at 8 weeks for the adductor-plasty and 10 to 12 weeks for the intrinsic tendon transfers.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The patient should be made aware of the prognosis and the need for regular physiotherapy, where indicated.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

When patients present with a claw hand, an interprofessional team that includes a hand surgeon, neurologist, neurosurgeon, physical therapist, emergency department physician, and nurse practitioner should be involved in the diagnosis and management. Because there are several causes of a claw hand, the initial referral should be to the neurologist. The treatment depends on the cause and extent of nerve injury.

The treatment depends on the acuteness of the condition and the severity of the injury. Physical and occupational therapy is necessary for all individuals.

Extensive rehabilitation is required, and patients should be urged to be compliant with treatment. Other comorbidities like diabetes should be treated, and the pharmacist should urge the patient to discontinue smoking and abstain from alcohol. Since many patients do develop anxiety and depression, a consult with a mental health nurse is recommended. The occupational and physical therapists should continue with exercises that strengthen the hand muscles. Close communication with the team is highly recommended to ensure good outcomes.

The prognosis for most patients is guarded.[11]