Continuing Education Activity

A craniotomy is a neurosurgical technique that entails opening a part of the skull to gain access to intracranial pathology. Headaches are frequently encountered after a craniotomy, presenting in over two-thirds of patients who have undergone the procedure. The pain's severity and duration can vary from person to person. Postcraniotomy headache (PCH) falls under the category of secondary headaches and can present unique challenges in diagnosis and management.

This activity for healthcare professionals is designed to enhance learners' skills in evaluating and managing PCH. Valuable insights will be gained to enable learners to work proficiently with an interprofessional team caring for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Identify the signs and symptoms indicative of a postcraniotomy headache.

Develop a diagnostic plan for evaluating a patient with a postcraniotomy headache, including relevant laboratory and imaging studies.

Create a personalized management plan for a patient with a postcraniotomy headache, including pharmacologic treatments, rehabilitative strategies, and referrals to other specialists if warranted.

Coordinate efforts with an interprofessional team caring for patients who have recently undergone craniotomy, determining short- and long-term rehabilitation and follow-up plans to improve outcomes.

Introduction

The calvaria is the upper part of the cranium that forms a protective box around the brain. The rest of the skull consists of the facial skeleton. The frontal bone forms the forehead. The right and left parietal bones form the calvaria's superolateral aspect. The occipital bone occupies the calvaria's posterior region. The sutures where these bones articulate are the coronal (frontal-parietal), sagittal (right and left parietal), and lambdoid (parietal-occipital). Removing the calvaria exposes the anterior, middle, and posterior cranial fossae at the skull base. Various foramina containing important neurovascular structures pass through the skull base.

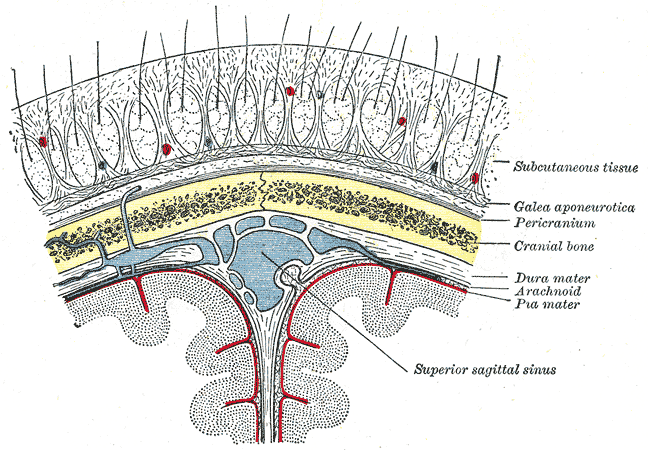

Five layers comprise the scalp, best remembered by the acronym "SCALP." From superficial to deep, these layers are the following (see Image. Relationship of the Meniges to the Skull and Brain):

- Skin: differs from the rest of the body's skin in having more hair follicles and sebaceous glands

- Connective tissue: a dense, highly vascular, and richly innervated subcutaneous layer

- Aponeurosis: also known as the epicranium and contains a tough, tendinous sheet covering the epicranius muscle; the occipitofrontalis and temporoparietalis compose the epicranial musculature

- Loose connective tissue: consists of a connective tissue matrix with many potential spaces, allowing free movement of the superficial layers; injury and infection may spread to other areas of the head through this layer

- Pericranium: the skull's periosteal covering

The endocranium is the fibrous membrane closely apposed to the skull's endosteum that also comprises the outer dura mater. The galea aponeurotica is a fibromuscular layer spanning from the occiput to the eyebrows. The meninges are the membranes protecting the brain, comprised of the dura mater (dura), arachnoid mater (arachnoid), and pia mater (pia). Of the 3 meningeal layers, the dura mater is the most superficial and loosely attached to the other layers. Neurosurgeons often make a dura mater incision to access the brain during craniotomy.

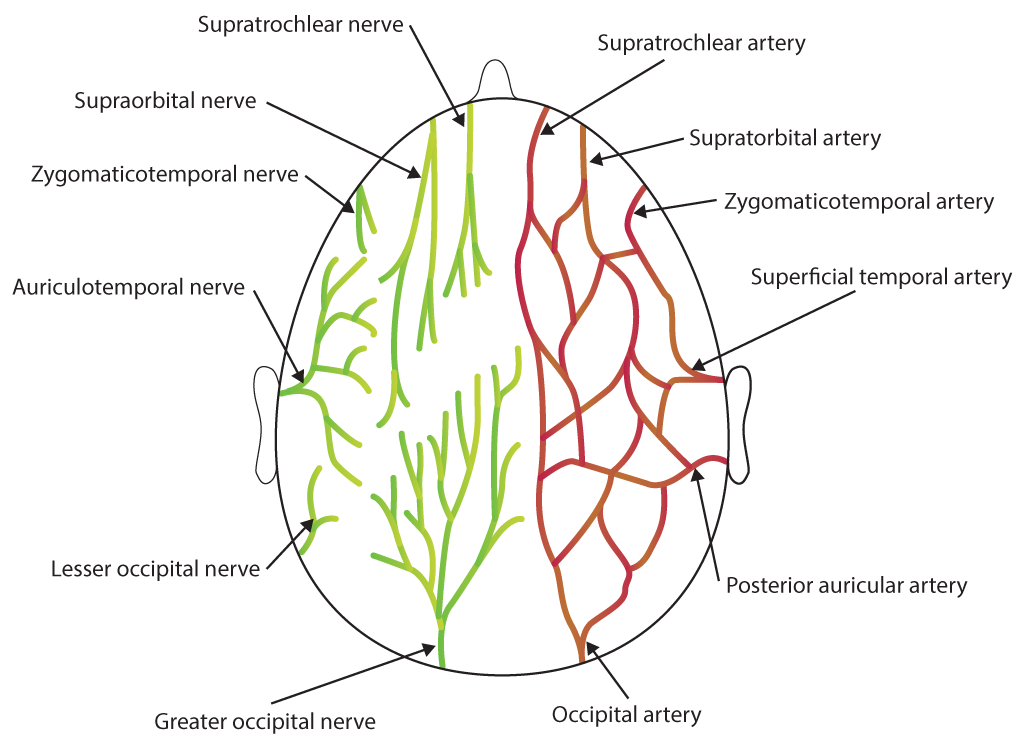

Scalp and dura mater innervation arises from the following (see Image. Scalp Nerves and Arteries):

- Trigeminal nerve

- C1 to C3 nerves

- Cervical sympathetic trunk

- Vagus nerve

- Hypoglossal nerve

- Facial nerve

- Glossopharyngeal nerve

A craniotomy is a neurosurgical technique that entails opening a part of the skull to access intracranial structures. Headaches frequently arise as an adverse effect of this procedure. Acute postcraniotomy headache (PCH) is defined as a headache developing within a few days of a surgical craniotomy lasting less than 3 months. In contrast, chronic PCH persists for more than 3 months after the craniotomy. PCH develops in over two-thirds of patients undergoing the procedure and can present unique challenges in diagnosis and management.[1][2]

Etiology

PCH is often multifactorial. The risk factors for this condition are the following:[3][4]

- Age: younger than 45 years

- Gender: women

- Approaches: skull base surgeries involving suboccipital and subtemporal approaches due to considerable dissection of major muscles

- Postsurgical cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage: orthostatic in nature and decreases with recumbency

- Neurosurgical duration: greater than 4 hours

- Type of tumor: higher incidence in individuals with astrocytomas and metastatic brain tumors

- Size of tumor: increased incidence of chronic PCH in patients with small-sized tumors

- Location of tumor: increased incidence in individuals with intraventricular and infratentorial tumors

- Direct closure of dura: increases the risk of pain compared to duraplasty

- Type of anesthesia: inhalational agents are associated with higher pain scores than total intravenous anesthesia

- Craniotomy vs craniectomy: Craniectomy is associated with a higher incidence of PCH [5]

- Comorbidities present: Preoperative headache, presence of uncontrolled anxiety or depression [6]

Factors that reduce PCH occurrence include bone dust removal and preoperative steroid administration.[7]

Epidemiology

The true incidence of PCH is unknown owing to methodological differences, case definition inconsistencies, and multiple surgical approaches used by retrospective reviews regarding this condition. However, looking broadly, most studies report that more than 30% of craniotomy patients develop acute PCH.[8] Chronic PCH, commonly seen after acoustic neuroma excision, has an incidence of 28.4% at 3 years postoperation.[9]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of chronic pain is still unclear at the molecular level. Some of the possible factors responsible include:

- Sensitization of central neurologic pain perception

- Structural changes in neurons in the central nervous system

- Hyperstimulation of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors in the raphe nuclei

- Changes in the serotonergic and hemodynamic system

- Role of catecholaminergic nerves

However, the most straightforward mechanism that can explain the evolution of this condition is direct trauma from the surgical procedure itself. Injury to the soft tissue, musculature, bone, or meninges results in peripheral nociceptor activation, leading to abnormal action potential transmission along afferent A-δ and C fibers and, subsequently, somatic pain.

Factors that may aggravate PCH include nerve injury, meningeal and internal tissue irritation from bone dust, muscle adherence to the dura, surgical scar neuroma formation, central sensitization, and aberrant nerve regeneration.[10]

History and Physical

On history, patients may report a continuous, pulsatile, or pounding pain of variable intensity, similar to a tension headache, that appears within 7 days of the surgery. The pain is typically ipsilateral to the surgical site, though generalized headaches have also been reported. The pain increases in frequency in the first few days but becomes less frequent over time. New sensory or motor deficits usually do not accompany PCH, and pathology must be suspected if new focal neurologic signs are observed. Patients may also report nausea, photophobia, anxiety, temporomandibular disorders, and depression in association with PCH. Response to analgesics and migraine medications varies.

Some individuals may have residual neurologic deficits even after a successful craniotomy. These patients' most recent neurologic examination results can serve as a baseline before performing a new one. Pathology must be ruled out in the presence of new focal neurologic signs.

Head and neck examination may reveal the presence of scar neuromas. Palpating this scar can reproduce the pain in patients with chronic PCH.[11]

Evaluation

PCH is a clinical diagnosis. However, when the diagnosis is doubtful, a non-contrast head computed tomography (CT) scan is recommended as the initial imaging modality to rule out a suspected intracranial pathology.

The current criteria for diagnosing PCH according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3 (ICHD-3) are summarized in the following table:

Table. Criteria for Diagnosing Postcraniotomy Headache

| Criteria for Acute Headache Attributed to Craniotomy |

|

Description. Headache is of less than 3 months duration caused by surgical craniotomy.

A. Any headache fulfilling criteria C and D

B. Surgical craniotomy has been performed

C. A headache is reported to have developed within 7 days after 1 of the following:

- The craniotomy

- Regaining consciousness following the craniotomy

- Discontinuation of medication(s) that impair the ability to sense or report a headache following the craniotomy

D. Either of the following:

- A headache has resolved within 3 months after the craniotomy

- A headache has not yet resolved, but 3 months have not yet passed since the craniotomy

E. Not properly accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis

|

| Criteria for Persistent Headache Attributed to Craniotomy |

|

Description. Headache is of greater than 3 months duration caused by surgical craniotomy.

A. Any headache fulfilling criteria C and D

B. Surgical craniotomy has been performed

C. A headache is reported to have developed within 7 days after 1 of the following:

- The craniotomy

- Regaining consciousness following the craniotomy

- Discontinuation of medication(s) that impair the ability to sense or report a headache following the craniotomy

D. Headache persisting for more than 3 months after the craniotomy

E. Not properly accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis

|

About a quarter of patients who experience acute PCH later develop persistent or chronic PCH. When a headache following craniotomy becomes persistent, the possibility of a medication-overuse headache should be considered.[12]

Chronic postcraniotomy pain can be divided into 4 grades based on severity[13]:

Grade-1: Patients have a minor annoyance

Grade-2: Headaches are present nearly every day

Grade-3: Patients require medicines every day

Grade-4: Patients feel incapacitated.

Patients can grade chronic headaches using the McGill Pain Questionnaire and Brief Pain Inventory scoring system.

Treatment / Management

Investigations about the best PCH management strategies are ongoing. Meanwhile, medications for headaches with similar phenotypes are widely used in current practice. However, care must be taken when prescribing drugs that may obscure the ability to monitor neurologic responses. Opioids are an example, which have additional risks like addiction and respiratory depression.[14]

For acute PCH, multimodal analgesia is recommended. Pharmacologic options include the following:

- Opioids: Codein, tramadol, morphine, fentanyl, and remifentanil

- Nonopioids: Paracetamol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), dexmedetomidine, gabapentinoids, dexamethasone, transdermal patches

Combining opioids and nonopioids reduces the risk of developing adverse events.[21] Some combinations successfully used in past studies are fentanyl-ketorolac and tramadol-diclofenac.

Chronic PCH may be managed depending on the cause. The usual management modalities include the following:

- Analgesics: Paracetamol, codeine, NSAIDS, tricyclic antidepressants, amitriptyline

- Anticonvulsants: Carbamezepine, sodium valproate, gabapentin, lamotrigine

- Sodium channel blockers: Lignocaine

- Sumatriptan

- Trigger-point injections

- Topical Capsaicin

- Botulinum toxin type A

- Surgical techniques: C2 gangliotomy, C2 ganglionectomy, C2 to C3 rhizotomy, C2 to C3 root decompression, distal neurectomy

- Neurolysis

- Occipital nerve stimulation

- Botulinum toxin-A

- Radiofrequency nerve ablation

- Cryoablation

- Manual neck traction

Alternative modalities may also be considered for patients with chronic PCH. Some options are physical therapy, stress management, neck collars, acupuncture, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, hot and cold packs, massage, and biobehavioral interventions. However, more research is required to support the use of alternative treatments for PCH.

Preventive strategies also comprise an important part of PCH management. Reducing the risk of this condition also minimizes exposure to potentially addictive treatments. The various PCH-preventive modalities include the following:

- Modification of surgical techniques, such as:

- Choosing craniotomy over craniectomy

- Closing the wound by applying methyl methacrylate between the dura and cervical muscles

- Using extradural abdominal fat graft for closure during retrosigmoid craniotomy instead of standard wound closure techniques

- Performing a duraplasty instead of direct dural closure

- Preemptive analgesia by scalp infiltration, scalp block, and preemptive NSAIDs

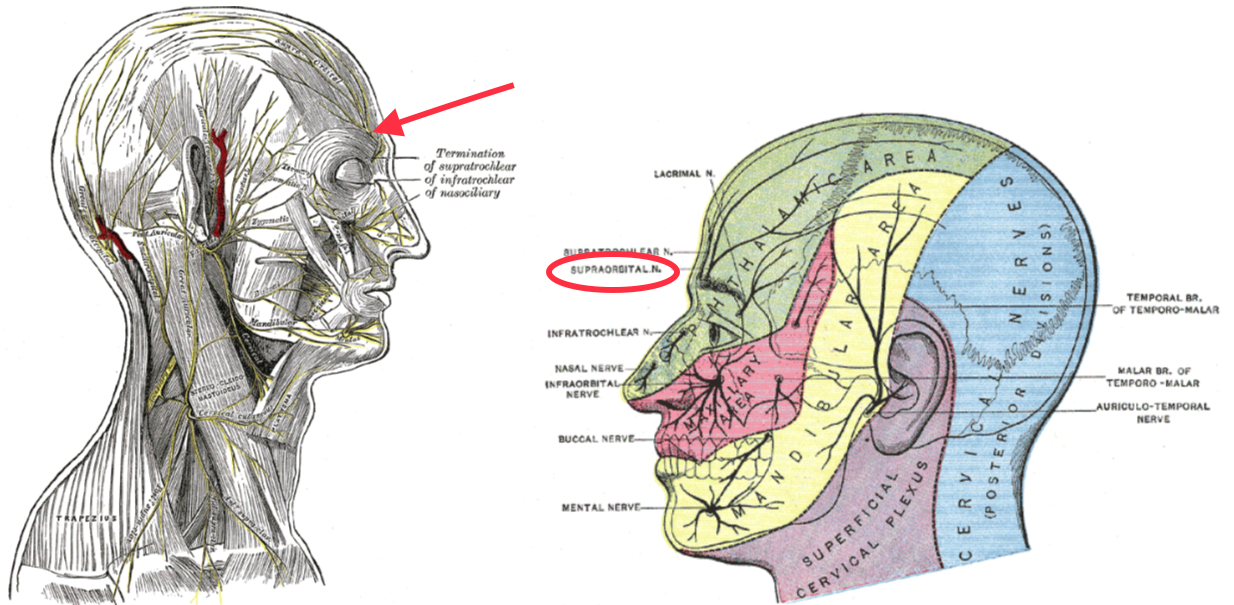

The dural and scalp nerves mentioned previously may be anesthetized with a ring block from the nasion to the external occipital protuberance or blocking the individual nerves. Meanwhile, nerves commonly targeted during a scalp block for PCH prevention include the following (see Image. Sensory Areas of the Head):

- Supraorbital nerve

- Supratrochlear nerve

- Zygomaticotemporal nerve

- Auriculotemporal nerve

- Lesser occipital nerve

- Greater occipital nerve

- Greater auricular nerve

Single-time wound instillation of ropivacaine (12 ml of 0.25%) through a surgical (subgaleal) drain during wound closure has proven beneficial to neurosurgical patients undergoing supratentorial craniotomy in a recent clinical trial. This treatment reduces postoperative pain, analgesic consumption, and early emergence in these individuals.[15]

Other treatments that have shown potential in preventing PCH in early studies are the following:

- Intravenous acetaminophen [16][17]

- Levetiracetam [18]

- Preoperative diclofenac

The following modalities are currently being studied:

- Preincisional infiltration with dexamethasone palmitate emulsion

- Local infiltration of flurbiprofen axetil [19][20]

Evidence is lacking regarding effective PCH preventive treatments 48 hours after surgery.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of PCH includes the following:

- Postsurgical cerebrospinal fluid leak

- Hydrocephalus

- Intracranial hemorrhage

- Other headache types, such as cervicogenic, tension, cluster, and migraine

- Medication-overuse headache

- Meningitis or intracranial other infection

- Temporomandibular joint disorder

A thorough clinical evaluation and appropriate imaging studies can differentiate these conditions from PCH.

Prognosis

PCH improves over time as the patient recovers from the surgical procedure. However, the prognosis may be influenced by the following factors:

-

Underlying cause: headaches associated with severe inflammation can take longer to resolve.

-

Management: patients respond variably to PCH treatment modalities.

-

Patient-specific factors: individual patient characteristics, such as pain tolerance, overall health, and the presence of preexisting medical conditions, can influence the course of postcraniotomy headaches.

-

Complications: postoperative complications like infections and CSF leaks can impact the prognosis.

-

Treatment compliance: patient adherence to postoperative care instructions impacts recovery from the procedure and, thus, PCH resolution.

-

Psychosocial factors: stress, anxiety, and other psychosocial factors can influence the perception and persistence of postcraniotomy headaches.

Patients experiencing postcraniotomy headaches should communicate any changes in symptoms or concerns to their healthcare team. Regular follow-up appointments allow for ongoing assessment and adjustments to the treatment plan as needed, ultimately contributing to a more favorable prognosis.

Complications

Acute PCH can evolve into the chronic type. Both acute and chronic PCH can cause stress and anxiety and reduce patients' functional levels and quality of life. Patients may also experience rebound headaches and adverse medication effects while treating the condition. Serious disorders like life-threatening intracranial pressure changes and meningitis must be ruled out if patients report changes in pain quality.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Preventive measures for PCH involve a comprehensive approach to minimizing the risk of headache development and hastening overall recovery. The following strategies may help reduce the frequency and severity of PCH:

-

Optimal pain management

-

Gradual tapering of pain medications

-

Hydration

-

Early mobilization to reduce muscle tension

-

Prophylactic medications, as discussed previously

-

Cautious use of caffeine to prevent caffeine withdrawal

-

Regular follow-up

-

Stress management

-

Addressing sleep disturbances

-

Identifying and avoiding triggers

Healthcare providers should work collaboratively with patients to develop a personalized plan that addresses their unique needs and optimizes their recovery after a craniotomy.

Pearls and Other Issues

The key points to remember when evaluating and managing PCH are the following:

- The diagnosis of PCH is made primarily using the ICHD-3 criteria.

- Anxiety and depression may exacerbate symptom intensity.

- Pharmacological management with opioid and nonopioid analgesics is widely used in practice.

- Nonpharmacological strategies help reduce opioid requirements and include scalp blocks and radiofrequency nerve ablation.

- PCH prevention is a valuable part of treatment because it minimizes exposure to potentially harmful treatments.

- Alternative modalities like acupuncture and massage may be considered in chronic cases, but these treatments have not been widely proven in clinical studies.

- PCH preventive treatments have not proven effective 48 hours after surgery.

- Acute and chronic PCH can reduce function and quality of life.

Patients with PCH require a comprehensive and individualized treatment approach, taking into account both the medical and psychosocial aspects of this condition.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing PCH requires the collaboration of an interprofessional healthcare team. This team may include the following providers:

- Neurosurgeon: the key member of the team who performs the craniotomy and makes decisions related to the surgical plan.

- Neurologist: plays a crucial role in evaluating and managing neurological symptoms, including headaches.

- Anesthesiologist: involved in perioperative care and postoperative pain management.

- Pain management specialist: can assist in developing a comprehensive pain management plan, considering both pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches to manage postcraniotomy headaches.

- Rehabilitation team: physical and occupational therapists and rehabilitation specialists can help reduce tension-related headaches, promote overall physical well-being, and regain functional independence in daily activities.

- Mental health professional: can address the psychological aspects of recovery, providing support for patients dealing with stress, anxiety, or mood disorders that may impact postcraniotomy headaches.

- Pharmacist: collaborates with the healthcare team to ensure appropriate medication management.

- Radiologist: interprets imaging studies to assess the surgical site and identify any complications that may contribute to postcraniotomy headaches.

- Primary care physician or pediatrician: essential for coordinating overall care, managing comorbid conditions, and ensuring continuity of care between hospital and outpatient settings.

Effective communication and collaboration among these team members are crucial for providing holistic, patient-centered care.