Continuing Education Activity

Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) is the sudden blockage of the central retinal artery, resulting in retinal hypoperfusion, rapidly progressive cellular damage, and vision loss. Retina survival depends on the degree of collateralization and the duration of retinal ischemia. Prompt diagnosis and early treatment to dislodge or lyse the offending embolus or thrombus is crucial to avoid irreversible retinal damage and blindness. This activity reviews the cause and presentation of central retinal artery occlusion and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

Review the etiology of central retinal artery occlusion.

Describe the workup of a patient with central retinal artery occlusion.

Summarize the treatment of central retinal artery occlusion.

Explain the importance of improving care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by central retinal artery occlusion.

Introduction

Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) is the sudden blockage of the central retinal artery, resulting in retinal hypoperfusion, rapidly progressive cellular damage, and vision loss. Retina survival depends on the degree of collateralization and the duration of retinal ischemia. Prompt diagnosis and early treatment to dislodge or lyse the offending embolus or thrombus is crucial to avoid irreversible retinal damage and blindness.[1]

Etiology

An embolism is the most common cause of CRAO. The three main types of emboli are cholesterol, calcium, and platelet-fibrin. Both cholesterol and platelet-fibrin emboli typically arise from atheromas in the carotid arteries. Calcium emboli typically arise from cardiac valves. On fundoscopy, calcium emboli appear white, cholesterol emboli (Hollenhorst plaques) appear orange, and platelet-fibrin emboli appear dull white.

In-situ thrombosis also may cause retinal artery occlusion. Thrombi may be due to atherosclerotic disease, collagen-vascular disease, inflammatory states, and/or hypercoagulable states. Predisposing conditions include but are not limited to polycythemia vera, sickle cell anemia, multiple myeloma, systemic lupus erythematosus, factor V Leiden, prothrombin III mutation, hyperhomocysteinemia, polyarteritis nodosa, giant cell (temporal) arteritis, antiphospholipid syndrome, activated protein C resistance, Behcet disease, and syphilis. Rapid differentiation between thromboembolic versus arteritic processes is important as optimal therapy differs and the rapid administration of steroids for vasculitic causes of CRAO is associated with improved outcomes.

Epidemiology

The incidence of CRAO is approximately 1 per 100,000 people with less than 2% presenting with bilateral involvement. Mean age at presentation is the early 60s. Men have a slightly higher incidence than women. Patients diagnosed with CRAO have a life expectancy of 5.5 years compared to 15.4 years for age-matched non-CRAO patients. Risk factors are similar to other thromboembolic diseases and include hypertension, smoking, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, hypercoagulable states, and male gender. Approximately one-third of patients with CRAO have clinically significant ipsilateral carotid artery stenosis.

Pathophysiology

The central retinal artery is the first intraorbital branch of the ophthalmic artery. It enters the optic nerve 1 cm posterior to the globe and supplies blood to the retina. Occlusion of the central retinal artery results in retinal ischemia, vision loss, and eventual necrosis. Acutely, CRAO results in retinal edema and pyknosis of the ganglion cell nuclei. As ischemia progresses the retinal becomes opacified and yellow-white in appearance. In experimental models of complete CRAO, permanent retinal damage occurs in just over 90 minutes.

In the clinical setting where occlusion may be incomplete, the return of vision may be achieved after delays of 8 to 24 hours. Approximately 15% of the population receives significant macular collateral circulation from the cilioretinal artery. Patients with this anatomical variant typically have less severe presentations and better long-term prognoses.

History and Physical

CRAO typically presents with sudden, painless, monocular vision loss that occurs over seconds. Patients may report an antecedent transient visual loss (amaurosis fugax) and often have a history of atherosclerotic disease.

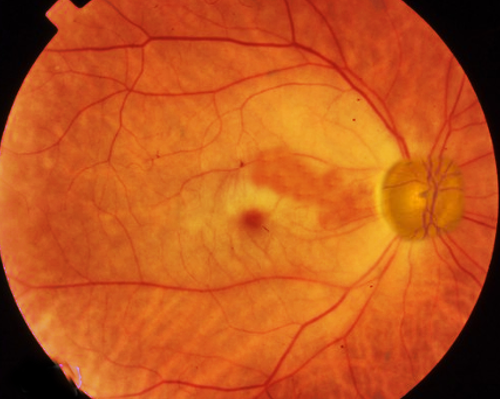

Patients with CRAO often present with monocular loss of light perception and an afferent pupillary defect. However, visual acuity can vary from loss of light perception to finger counting. Typically, intraocular pressures, anterior chamber exam, and extraocular eye movements are within normal limits. A thorough fundoscopic exam is crucial for accurate diagnosis of CRAO, and a dilated exam should be performed on any patient without contradictions to mydriatic medications who presents with symptoms concerning for CRAO. On fundoscopy, the retina will appear diffusely pale with a cherry red central spot. This spot results from the preserved choroidal circulation visible beneath the thin fovea. Narrowing, "boxcarring" or segmentation of the arterioles also may be appreciated. Rarely, arteriolar emboli may be visualized. Other conditions may present with a cherry red spot on fundoscopic exams (commotio retinae, Tay-Sachs, Niemann-Pick disease) but should be easy to differentiate based on clinical presentation.

Evaluation

CRAO is analogous to a cerebral vascular accident involving the retina. As such, workup for CRAO closely parallels the workup for stroke or transient ischemic attacks.

Initial blood work should include point-of-care glucose, complete blood count with differential, and coagulation assays (PT/INR, PTT).

An erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein should be obtained to rule out giant cell (temporal) arteritis. If inflammatory markers are elevated and the history and physical are consistent with giant cell arteritis, then high dose steroids should be initiated immediately.

If symptom onset is less than 6 hours, a CT head without contrast should be obtained to rule out intracranial hemorrhage and determine if the patient is a candidate for thrombolytic therapy.

Other workup should be considered based on individual risks factors and history. This may include hemoglobin A1c, lipid profile, Rh factor, antinuclear antibody, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test, hypercoagulability labs, carotid artery duplex, electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, and outpatient Holter monitoring. [2]

If available, consider intravenous fluorescein angiography and/or electroretinography to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment / Management

There is no consensus about the optimal treatment for CRAO, although early administration of intravenous thrombolytics shows promise. [3] All proposed therapies are aimed at restoring retinal perfusion/oxygenation. Improvement has been reported with the following therapies.[4][5]

- Immediate digital ocular massage to induce oscillations of intraocular pressure and dislodge the offending thrombus.

- Intraocular pressure reduction with acetazolamide, mannitol, topical timolol, or anterior chamber paracentesis (often recommended in conjunction with digital ocular massage).

- Hyperventilation into a paper bag or inhaled 10% carbon dioxide to induce respiratory acidosis and vasodilation.

- Supplemental oxygen.

A literature review by Murphy-Lavoie H et al. in 2012 recommended supplemental oxygen for any patient presenting within 24 hours of vision loss with signs and symptoms that cause concern for CRAO. They report minimal risk associated with oxygen therapy and suggest that early therapy may prevent retinal damage. Oxygen should be initiated at the highest tolerable fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2). If available, hyperbaric oxygen therapy should be considered.[6]

A meta-analysis by Schrag et al. in 2015 found that fibrinolysis was beneficial within 4.5 hours of symptom onset (with a number needed to treat of 4.0). Additionally, they found that the addition of aggressive non-fibrinolytic therapies such as ocular massage, anterior chamber paracentesis, and hemodilution worsened visual outcomes (with a number needed to harm of 10). A randomized control trial is warranted to better elucidate the role of early systemic thrombolytic therapy for CRAO.[7]

Differential Diagnosis

- Acute angle-closure glaucoma in emergency medicine

- Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION)

Pearls and Other Issues

Do not forget inflammatory markers such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. If CRAO is due to giant cell arteritis, then early diagnosis and rapid steroid administration are essential to halt vision loss.

Fundoscopy is the diagnostic gold standard. A dilated exam should be performed on any patient without contradictions to mydriatic medications who presents with symptoms concerning for CRAO.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Healthcare workers including nurse practitioners who see patients with vision loss or blindness should refer these patients promptly to an ophthalmologist. Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) is the sudden blockage of the central retinal artery, resulting in retinal hypoperfusion, rapidly progressive cellular damage, and vision loss. Retina survival depends on the degree of collateralization and the duration of retinal ischemia. Prompt diagnosis and early treatment to dislodge or lyse the offending embolus or thrombus is crucial to avoid irreversible retinal damage and blindness. The prognosis for these patients depends on the timing of diagnosis and initiation of treatment. Those who are treated promptly do get the sight back but in those in whom there is a delay, there is always some degree of vision loss and in some cases permanent blindness.