[1]

Millar AJ, Rode H, Cywes S. Malrotation and volvulus in infancy and childhood. Seminars in pediatric surgery. 2003 Nov:12(4):229-36

[PubMed PMID: 14655161]

[2]

Birajdar S, Rao SC, Bettenay F. Role of upper gastrointestinal contrast studies for suspected malrotation in neonatal population. Journal of paediatrics and child health. 2017 Jul:53(7):644-649. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13515. Epub 2017 Apr 20

[PubMed PMID: 28425590]

[3]

Pelayo JC, Lo A. Intestinal Rotation Anomalies. Pediatric annals. 2016 Jul 1:45(7):e247-50. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20160602-01. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 27403672]

[4]

Sivakumar A, Mahadevan A, Lauer ME, Narvaez RJ, Ramesh S, Demler CM, Souchet NR, Hascall VC, Midura RJ, Garantziotis S, Frank DB, Kimata K, Kurpios NA. Midgut Laterality Is Driven by Hyaluronan on the Right. Developmental cell. 2018 Sep 10:46(5):533-551.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.08.002. Epub 2018 Aug 30

[PubMed PMID: 30174180]

[5]

Strouse PJ. Disorders of intestinal rotation and fixation ("malrotation"). Pediatric radiology. 2004 Nov:34(11):837-51

[PubMed PMID: 15378215]

[6]

Nagdeve NG, Qureshi AM, Bhingare PD, Shinde SK. Malrotation beyond infancy. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2012 Nov:47(11):2026-32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.06.013. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 23163993]

[7]

Adams SD, Stanton MP. Malrotation and intestinal atresias. Early human development. 2014 Dec:90(12):921-5. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2014.09.017. Epub 2014 Oct 13

[PubMed PMID: 25448782]

[8]

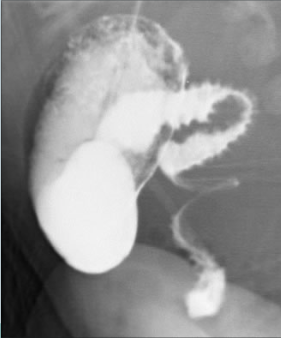

Applegate KE, Anderson JM, Klatte EC. Intestinal malrotation in children: a problem-solving approach to the upper gastrointestinal series. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2006 Sep-Oct:26(5):1485-500

[PubMed PMID: 16973777]

[9]

Shah MR, Levin TL, Blumer SL, Berdon WE, Jan DM, Yousefzadeh DK. Volvulus of the entire small bowel with normal bowel fixation simulating malrotation and midgut volvulus. Pediatric radiology. 2015 Dec:45(13):1953-6. doi: 10.1007/s00247-015-3430-9. Epub 2015 Jul 26

[PubMed PMID: 26209961]

[10]

Reddy AS, Shah RS, Kulkarni DR. Laparoscopic Ladd'S Procedure in Children: Challenges, Results, and Problems. Journal of Indian Association of Pediatric Surgeons. 2018 Apr-Jun:23(2):61-65. doi: 10.4103/jiaps.JIAPS_126_17. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29681694]

[11]

Tsumura H, Ichikawa T, Kagawa T, Nishihara M. Successful laparoscopic Ladd's procedure and appendectomy for intestinal malrotation with appendicitis. Surgical endoscopy. 2003 Apr:17(4):657-8

[PubMed PMID: 12574927]

[12]

Isani MA, Schlieve C, Jackson J, Elizee M, Asuelime G, Rosenberg D, Kim ES. Is less more? Laparoscopic versus open Ladd's procedure in children with malrotation. The Journal of surgical research. 2018 Sep:229():351-356. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.04.016. Epub 2018 May 11

[PubMed PMID: 29937013]

[13]

Bass KD, Rothenberg SS, Chang JH. Laparoscopic Ladd's procedure in infants with malrotation. Journal of pediatric surgery. 1998 Feb:33(2):279-81

[PubMed PMID: 9498402]

[14]

Arnaud AP, Suply E, Eaton S, Blackburn SC, Giuliani S, Curry JI, Cross KM, De Coppi P. Laparoscopic Ladd's procedure for malrotation in infants and children is still a controversial approach. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2019 Sep:54(9):1843-1847. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.09.023. Epub 2018 Oct 28

[PubMed PMID: 30442460]

[15]

Catania VD, Lauriti G, Pierro A, Zani A. Open versus laparoscopic approach for intestinal malrotation in infants and children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatric surgery international. 2016 Dec:32(12):1157-1164

[PubMed PMID: 27709290]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[16]

Huntington JT, Lopez JJ, Mahida JB, Ambeba EJ, Asti L, Deans KJ, Minneci PC. Comparing laparoscopic versus open Ladd's procedure in pediatric patients. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2017 Jul:52(7):1128-1131. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.10.046. Epub 2016 Oct 30

[PubMed PMID: 27856011]

[17]

Kulaylat AN, Hollenbeak CS, Engbrecht BW, Dillon PW, Safford SD. The impact of children's hospital designation on outcomes in children with malrotation. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2015 Mar:50(3):417-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.08.011. Epub 2014 Sep 8

[PubMed PMID: 25746700]

[18]

Seashore JH, Touloukian RJ. Midgut volvulus. An ever-present threat. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 1994 Jan:148(1):43-6

[PubMed PMID: 8143008]

[19]

Marseglia L, Manti S, D'Angelo G, Gitto E, Salpietro C, Centorrino A, Scalfari G, Santoro G, Impellizzeri P, Romeo C. Gastroesophageal reflux and congenital gastrointestinal malformations. World journal of gastroenterology. 2015 Jul 28:21(28):8508-15. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i28.8508. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26229394]