Continuing Education Activity

The nasal choanae are paired openings that connect the nasal cavity with the nasopharynx. Choanal atresia is a congenital condition in which these openings are occluded by membranous soft tissue, bone, or a combination of both due to failed recanalization of the nasal fossae during fetal development. If unilateral, it presents with unilateral mucopurulent discharge. If bilateral, the neonate is unable to breathe. Since newborns are obligate nasal breathers, establishing an airway is an acute otolaryngologic emergency. The interprofessional team should promptly recognize this condition to avoid severe morbidity and mortality.

Objectives:

- Outline the presenting features of unilateral versus bilateral choanal atresia.

- Describe how choanal atresia is diagnosed.

- Explain how and when to implement acute and definitive management of choanal atresia.

- Explain how the interprofessional team can work collaboratively to prevent the potentially profound complications of choanal atresia by applying knowledge about the presentation, evaluation, and management of this disease.

Introduction

Choanal atresia is a congenital disorder in which the nasal choanae, (i.e., paired openings that connect the nasal cavity with the nasopharynx), are occluded by soft tissue (membranous), bone, or a combination of both, due to failed recanalization of the nasal fossae during fetal development. If unilateral, it presents with unilateral mucopurulent discharge. If bilateral, the neonate is unable to breathe. Since newborns are obligate nasal breathers, establishing an airway is an acute otolaryngologic emergency.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Nasal choanae develop between the third and seventh embryonic weeks, following the rupture of the vertical epithelial fold between the olfactory groove and the roof of the primary oral cavity (stomodeum). The following theories have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of choanal atresia: the persistence of the buccopharyngeal membrane, the persistence of the nasobuccal membrane of Hochstetter, the incomplete resorption of the nasopharyngeal mesoderm, and the local misdirection of neural crest cell migration. These theories are associated with molecular and genetic studies to give further insights into the pathogenesis of choanal atresia.[4][5]

Epidemiology

The incidence of this malformation is between 1:5000 and 1:8000 live births. It is more often unilateral than bilateral (60% vs. 40%) and occurs more frequently in females than in males (ratio 2:1).

Pathophysiology

Current knowledge of the pathophysiology of the respiration of the neonate led to the conclusion that the infant, except when crying, is an obligate nasal breather. This is due to the elevated laryngeal position in the newborn as compared to the adult. When neonate swallows, the larynx touches the nasopharynx and locks between the soft palate and side of the nasopharynx. During inspiration, the neonate sucks the tongue, and a vacuum is created in the oropharynx, which helps to move soft tissue of the floor of the mouth up and back towards the soft palate. During expiration, the pressure in the airway causes the soft palate to push forward against the soft tissue and the tongue in the mouth, also obstructing the oral airway. As a result, the infant with bilateral choanal atresia experiences episodes of asphyxia and severe distress in quiet respiration when its mouth is closed, especially during periods of sleep or during feeding. The infant will become cyanotic, which is relieved by crying or gasping when the child opens the mouth widely, releasing the air obstruction.

Histopathology

Past reports mention that the malformation was made up of 90% bony and 10% membranous tissue. CT workup and histologic specimens show approximately 30% pure bone atresia and 70% mixed membranous and bone atresia with no purely membranous anomalies present.

History and Physical

Clinical presentation of choanal atresia varies from acute life-threatening airway obstruction to chronic recurrent nasal discharge on the affected side, depending on a unilateral or bilateral nature of the abnormality. In the case of bilateral choanal atresia, affected infants have episodes of acute respiratory distress with cyanosis that is relieved with crying and with the return of cyanosis with rest (paradoxical cyanosis). Feeding difficulty can be the initial alerting event in which the infants can present with progressive airway obstruction and choke episodes during feeding because of their inability to breathe and feed at the same time. Unilateral choanal atresia rarely present with infant respiratory distress. The most common presentation is a purulent nasal discharge and obstruction on the affected side and/or a history of chronic sinusitis. In some cases, the correct diagnosis is not reached until adulthood due to the non-specific symptoms of unilateral nasal obstruction. Choanal atresia may be associated with various other anomalies, CHARGE syndrome is the most common of these and consists of coloboma, heart disease, atresia choanae, growth, and mental retardation, genital hypoplasia, and ear anomalies.[6][7][8]

Evaluation

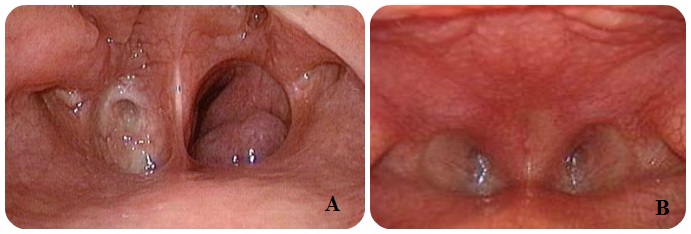

The diagnosis of this condition should be done immediately after birth. The initial clinical evaluation includes placing a laryngeal mirror under the nostril to check for fogging and introducing a suction catheter through each nostril and into the child's oral cavity. The clinical suspicion of choanal atresia can be confirmed by examination with a flexible nasal endoscope in a newborn with proper preparation, such as nasal decongestion and mucous suctioning, allowing direct visualization of the possible obstruction in the nasal passage. To confirm the diagnosis of choanal atresia, a CT scan should be done to further delineate characteristics of the malformation, such as the anatomy of the atretic area, including the thickness of the atretic plate and the presence and thickness of a bony plate. Besides delineating the nature and severity of choanal atresia, CT is also useful in differentiating other causes of nasal obstruction from choanal atresia. Differential diagnoses include pyriform aperture stenosis, nasolacrimal duct cysts, turbinate hypertrophy, septal dislocation and deviation, antrochoanal polyp, or nasal neoplasm.

Treatment / Management

The treatment of choanal atresia is essentially surgical. The objectives are to restore choanal patency, not to interfere with the patient normal craniofacial development, to minimize invasiveness, and to avoid recurrences. Unilateral choanal atresia does not require surgical treatment as urgently as the bilateral case and can be postponed until school-age when the anatomy of the region is more similar to that in adults. However, it needs to be closely monitored for any signs of a breathing problem. Using a nasal saline spray can also help to keep the nasal route clear. The acute care of infants with bilateral choanal atresia in asphyxia consists of endotracheal intubation or when available, may be utilized a McGovern nipple to maintain an adequate oral airway, consisting in an intraoral nipple with a large opening by cutting its end off, secured in the mouth with ties around the infant’s occiput, followed by perforation of the atresia plate. Five different surgical approaches have been proposed, including transpalatal, transeptal, sublabial, transantral, and transnasal. The transpalatal approach was the most frequently used until the advent, in the last decades, of the endoscopic endonasal approach. The growing experience in both instrumentation and technique in endoscopic sinus surgery have led many surgeons to make more frequent use of the endoscopic endonasal technique for the repair of choanal atresia, which has provided better results and fewer surgical complications than in traditional procedures. The use of choanal stenting and mitomycin C as an adjunct therapy to prevent restenosis are a controversial topic in the management of choanal atresia as there is no clear-cut evidence on the effectiveness of using stents or mitomycin after choanal atresia repair.[9][10]

Differential Diagnosis

- Isolated piriform aperture stenosis

Pearls and Other Issues

When presented with a child with nasal/upper airway obstruction or respiratory distress, choanal atresia must be considered in the differential diagnosis. In particular, bilateral choanal atresia should be considered in a neonate who turns cyanotic with feeding and improves with crying. The choanal atresia is, especially in its bilateral form, a medical-surgical emergency, which requires timely treatment. Given the high frequency of this malformation's association with syndromic pictures, among which the most frequently found is the CHARGE, it is important not to neglect the search for other congenital anomalies that can complicate the clinical picture. The endoscopic endonasal technique should be considered the first choice for the surgical treatment of choanal atresia as it offers a direct approach to the atretic plate, reduces intraoperative bleeding, reduces hospitalization time, and lowers morbidity.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

When healthcare workers are presented with a child with nasal/upper airway obstruction or respiratory distress, an interprofessional team approach involving nurses and clinicians is necessary for the safe management of the patient. The team must consider choanal atresia in the differential diagnosis. In particular, bilateral choanal atresia should be considered in a neonate who turns cyanotic with feeding and improves with crying. The choanal atresia is, especially in its bilateral form, a medical-surgical emergency, which requires timely treatment. Neonatal nurses should notify the team if there are any signs of this condition. Coordination with neonatologists and otolaryngologists is needed. Many of these infants have the CHARGE syndrome and hence an interprofessional approach to the workup is necessary

For stable infants with choanal atresia, the endoscopic endonasal technique should be considered the first choice for the surgical treatment of choanal atresia as it offers a direct approach to the atretic plate, reduces intraoperative bleeding, reduces hospitalization time, and lowers morbidity. [Level V]