Continuing Education Activity

Cleft lip deformity is one of the most common congenital deformities, and management requires an interprofessional approach to address the physical cleft deformity along with resulting issues in speech and swallowing. Many types of cleft lip deformity can occur, often simultaneously with a cleft palate. A microform or occult cleft occurs when the patient has incomplete separation of the lip with distortion but not separation of the white roll/vermillion border. An incomplete cleft lip has lip separation through the white roll/vermillion border and often a downward displacement of the ala but an intact nasal sill with a fibrous band called a Simonart band. A complete cleft lip has complete separation of lip and nasal sill. Patients also can have either unilateral or bilateral cleft lips. This activity reviews the evaluation, treatment, and complications of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and underscores the importance of an interprofessional team approach to its management.

Objectives:

- Outline the developmental pathophysiology that leads to cleft lip.

- Describe the history, physical, and evaluation necessary in a patient presenting with cleft lip.

- Review the treatment and management options for cleft lip patients.

- Explain the importance of interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to aid in prompt diagnosis of cleft lip and improving outcomes in patients diagnosed with the condition.

Introduction

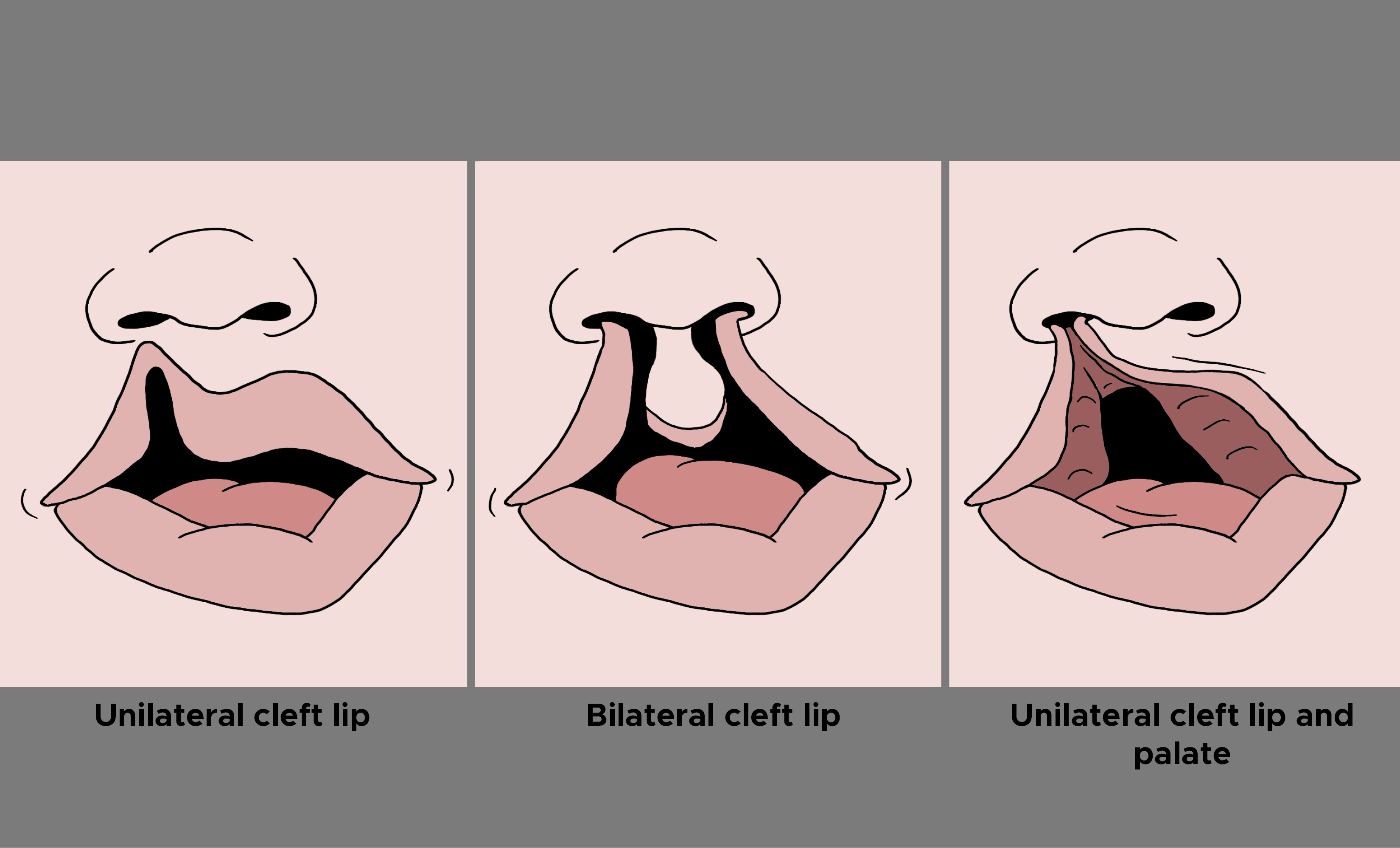

Cleft lip deformity is one of the most common congenital deformities, and management requires an interprofessional approach to address the physical cleft deformity along with resulting issues in speech and swallowing. Many types of cleft lip deformity can occur, often simultaneously with a cleft palate. A microform or occult cleft occurs when the patient has incomplete separation of the lip with distortion but not separation of the white roll/vermillion border. An incomplete cleft lip has lip separation through the white roll/vermillion border and often a downward displacement of the ala but an intact nasal sill with a fibrous band called a Simonart band. A complete cleft lip has complete separation of lip and nasal sill. Patients also can have either unilateral or bilateral cleft lips.[1][2]

Children with cleft lip often require multiple surgeries and interprofessional care. The costs of managing cleft lip is enormous; in addition, many of these children are left with lifetime psychological problems.

Etiology

At three to six weeks gestation, the nose and lip develop from embryonic structures, which are contributions of the 1st and 2nd pharyngeal arches and referred to as the two lateral nasal processes, the two medial nasal processes of the frontonasal prominence, and the two maxillary processes. The nasal alae are a result of the lateral nasal processes. The medial nasal processes give rise to the nasal tip, columella, philtrum, and premaxilla. Cleft lips, which usually involve clefts of the primary palate anterior to the incisive foramen, occur due to lack of fusion of the medial nasal process of the frontal nasal prominence with the maxillary process. Of note, the medial nasal processes coalesce in the midline to form an intermaxillary segment, and then connect to each of the lateral nasal processes. Failure of either of these occurrences can result in clefts involving the nose. [3][4]

Epidemiology

In males, cleft lips most commonly occur on the left side. There is a 0.1% overall risk of cleft lip with or without cleft palate in the general population. In the Asian population, cleft lip is more common, with 2 out of 1000 babies born with cleft lip versus 1 out of 1000 in Caucasians and 0.5 out of 1000 in African Americans. Twenty-nine percent of children with cleft lip have associated congenital malformations. Cleft lip formation is most likely influenced by a patient’s genetic make-up but is multi-factorial. An expectant mother's malnourishment as well as exposure to phenytoin, steroids, tobacco, alcohol, and Accutane is known to increase the likelihood of cleft lip deformity. Folate, however, has been found to be preventative for cleft lip formation.[5][6]

Pathophysiology

Patients with cleft lips have altered anatomy, including a short philtrum with one or both of the philtral columns affected as well as an abnormal orbicularis oris which is inserted into the cleft margin and alar wing. In addition, the children will have a predictable pattern of nasal deformities including a caudally dislocated nasal septum separated from a displaced anterior nasal spine of the maxilla, a shortened columella, attenuated flattened lower lateral nasal cartilage on the cleft side with the flared alar base, and an inferiorly rotated upper later nasal cartilage. Also, patients with cleft lips inherently will have some degree of the alveolar cleft with potential for collapse of the maxillary arch and class III malocclusion (the maxillary teeth sit posterior to the mandibular teeth). These hard and soft tissue anatomic changes translate to the various changes in appearance, speech, and swallowing/feeding seen in cleft lip patients. [7]

Cleft lip usually develops at the junction between the lateral and central segments of the upper lip. The cleft usually affects the upper lip and may extend into the maxilla and palate.

History and Physical

The first evaluations of patients with cleft lip occur at an early age as the physical appearance is readily noted on examination after birth. In early cleft evaluation, one must note concomitant cleft palate as this will have several implications on feeding, swallowing, and speech. One should note the width of the cleft, whether the cleft is unilateral or bilateral, and whether it is incomplete or complete. Alveolar clefts should also be noted carefully. In bilateral clefts, the premaxilla may be anteriorly displaced, which may require intervention before surgery with naso-alveolar molding (NAM).

Evaluation

It is vital for cleft care to involve an interprofessional team early on and to evaluate the patient from head to toe for other medical comorbidities and associated syndromes. Pediatric/neonatal intensive care teams are vital to the early care of these children for required medical needs. Genetics consults for patients in whom an associated syndrome is suspected are important. Any abnormalities noted should receive indicated work-up. Speech-language therapists and nutrition consults are usually required to teach parents techniques to meet the special feeding needs of these children. When patients do not meet feeding requirements for adequate nutrition, which is most common when there is a concomitant cleft palate, feeding access is sometimes required with the assistance of the pediatric surgery team. Establishment of care with orthodontists and plastic surgeons or otolaryngologists who specialize in patients with cleft lip deformity is important to assess the need for interventions and follow these patients long term. [8][9] Today, antenatal ultrasound can easily diagnose cleft deformity during the second trimester.

Treatment / Management

In neonates with a cleft lip the three major concerns are:

- Difficulties with feeding

- Risk of aspiration

- Airway obstruction

Treatment of patients with cleft lip deformity is a long-term commitment. Medical treatment will largely focus on requirements from any concomitant congenital abnormalities and based on nutritional needs. Within the first few weeks to months of life, NAM can be employed with assistance from an orthodontist. This involves the creation of an orthodontic appliance that molds a protruding premaxillary segment and alveolar process into a more favorable position. This allows for repositioning of the alveolar segments, medialization of the alar base, and columellar lengthening, which allows for easier surgical repair of cleft lip and nasal cleft deformity down the line. These require frequent adjustments by the orthodontist. Other treatment adjuncts that assist with decreasing the severity/width of the cleft early on are lip taping (often performed in patients with less severe clefts) and lip adhesion (an approximation of the cleft lip edges without changing lip landmarks or disturbing tissue required for definitive closure, often used in patients with wide clefts who are poor NAM candidates for social or geographic reasons).

Surgical intervention for initial cleft lip usually occurs at 3 to 5 months of age. A good rule of thumb in deciding the age at which is it safe to perform primary cleft lip repair is the "Rule of 10s.” If the infant is ten weeks old, 10 pounds, and hemoglobin has reached 10mg/dL, surgical repair should be safe if no other comorbidities preclude it. There are many accepted surgical techniques for primary repair of unilateral (Millard repair rotation advancement, Fisher repair, and Mohler repair) and bilateral (Mulliken repair) cleft lips, and the surgical details are out of the scope of this article. However, common goals in all repairs are to re-establish a competent orbicularis oris muscle, lengthen the philtrum and lip, and minimize visible scarring. In primary cleft repair, some surgeons perform gingivoperiosteoplasty, which involved the elevation of the mucoperiosteal flaps along an alveolar segment with wide-undermining to promote bone growth along the periosteum, but this is not a universal practice. [10][11] Because many of these children also have otitis media, it is important to have an ENT specialist involved in the care. During the cleft lip repair, ventilation tubes are placed but children continue to have eustachian tube dysfunction for many years.

Postoperatively, these patients are followed by multiple specialties from infancy into adulthood. Concomitant cleft palate repair is ideally performed from 9 to 12 months followed by close speech evaluation and follow up at 2 to 3 years of age to rule out any concomitant issues with swallowing or speech. A concomitant cleft palate can result in speech and swallowing issues as a result of anatomic abnormalities that result from the inability of the soft palate to rise against the posterior pharyngeal wall and separate the nasopharynx from the oropharynx (referred to as velopharyngeal insufficiency). Alveolar bone grafting, generally using cancellous bone from the iliac crest to close the alveolar gap is performed at 7 to 9 years of age per the discretion of the orthodontist when the permanent maxillary canines erupt. Following this, surgeries with ear, nose, and throat specialist or plastic surgeon for correction of nasal cleft deformity and scar revisions as well as orthodontics are done at various ages depending on the patient's needs. Final evaluation at the age of skeletal maturity, generally from 16 to 18 years of age, will evaluate the need for orthognathic surgery to create different pattern osteotomies in the mandible or midface/maxilla to correct various skeletal abnormalities associated with cleft lip deformity.

Differential Diagnosis

- Acute primary hepatitis stomatitis

Complications

- Hypertrophic scarring

- Poor cosmesis

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative feeding in infants with cleft lip needs special attention. Conventional feeding strategies i.e. breastfeeding or bottle-feeding are generally avoided in the post-operative period to minimize the tension on the wound. [12] Surgeons more often advise spoon-feeding as an alternative feeding strategy. Apart from spoon-feeding, various other modes including syringes, cups, soft nipples, etc have also been tried by clinicians across the globe. Although a considerable proportion of surgeons support the idea of an alternative feeding strategy, there are some that oppose this practice. There is sufficient literature highlighting the inconsolable crying and wriggling of the infant after the introduction of alternative feeding methods in the post-operative period. [12] This results in poor feeding and in turn affect wound healing. Thus, major changes in feeding may cause weight loss in the infant making a particular alternative method counterproductive. Therefore, alternative feeding methods must be encouraged in children who have undergone cleft lip repair to avoid unnecessary tension on the operated area, but the issue of increased wound dehiscence due to the continuation of conventional feeding strategies is still not proven.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Overall, it cannot be stressed enough that proper care of each cleft lip patient takes a collaborative effort between multiple specialties. The techniques and timing of medical interventions and surgeries mentioned here are a consensus in the current practice, but there is a wide variation based on geographic location and resources. Ultimately, treatment must always be tailored to the individual. In all cases, treatment of cleft lip requires an interprofessional team from many disciplines; and often these children need to be followed for many years.

Nurses who look after these infants should be fully aware of the risk of aspiration, airway obstruction, and difficulties with feeding. There is no single method of feeding that works in all children and the mother should be educated on the different techniques to help the infant latch on the nipple. Similarly, there is no one ideal bottle or nipple that can help infants with cleft lip suck. In general, the recommendations are a soft nipple that may need to be angled.

As the child grows, he or she may require training from a speech therapist. A nurse practitioner should follow the child as an outpatient and if any issues come up, the interprofessional team should be notified. Most children need countless dental visits to assess dental growth and alignment.

Because of the cost of cleft lip repair easily runs into 6 figures, a social worker should be involved to ensure that no child is denied care and is provided with all support necessary.

Since facial aesthetics are compromised, most children need some type of emotional support; hence a mental health nurse should provide counseling.

Finally, the mother should be taught about the potential for aspiration and choking. If the infant fails to gain weight, a visit to the pediatrician is highly recommended.[13][14]

This is one condition where no one should make unilateral decisions about treatment; all issues should be discussed with the interprofessional team first.