Continuing Education Activity

Bacterial endocarditis refers to infection of the endocardial surface of the heart. It usually involves heart valves, but it can occur on the endocardium or intracardiac devices. Acute endocarditis is a febrile illness that rapidly damages cardiac structures and spreads hematogenously which can progress to death within weeks if not treated. Subacute endocarditis has a slower disease process and may be present for weeks to months with gradual progression unless complicated by major embolic event or ruptured structure. This activity reviews the cause, pathophysiology, and presentation of bacterial endocarditis and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of bacterial endocarditis.

- Review the presentation of a patient with bacterial endocarditis.

- Summarize the treatment and management options available for bacterial endocarditis.

- Explain the interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication regarding the management of patients with bacterial endocarditis.

Introduction

Bacterial endocarditis refers to infection of the endocardial surface of the heart. It usually involves heart valves, but it can occur on the endocardium or intracardiac devices.

There are two types:

- Acute endocarditis is a febrile illness that rapidly damages cardiac structures and spreads hematogenously which can progress to death within weeks if not treated.

- Subacute endocarditis has a slower disease process and may be present for weeks to months with gradual progression unless complicated by major embolic event or ruptured structure.[1]

Etiology

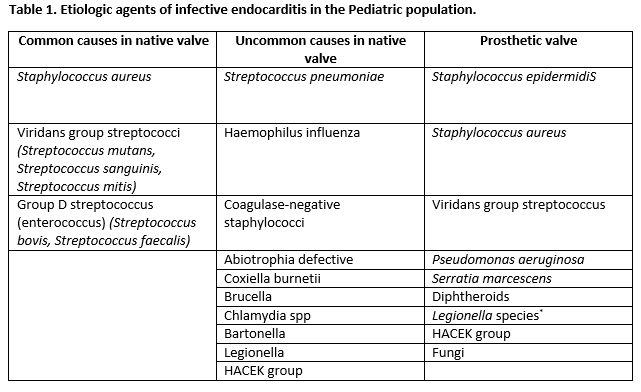

Most cases are caused by viridans streptococci, Streptococcus gallolyticus, Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci, HACEK organisms (Haemophilus, Aggregatibacter, Cardiobacterium, Eikenella, Kingella), and enterococci. Rarer organisms include pneumococci, Candida, gram-negative bacilli, and polymicrobial organisms.[1]

Epidemiology

In developed countries, the incidence of endocarditis ranges from 2.6 to 7 cases per 100,000 population per year. The median age of patients with endocarditis is 58 years.

Risk factors

Age greater than 60 years, male gender, injection drug use, history of prior infective endocarditis, poor dentition or dental procedure, presence of a prosthetic valve or intracardiac device, history of valvular disease (rheumatic heart disease, mitral valve prolapse, aortic valve disease, mitral regurgitation, etc), congenital heart disease (aortic stenosis, bicuspid aortic valve, pulmonary stenosis, ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, coarctation of the aorta, and tetralogy of Fallot), indwelling intravenous catheter, immunosuppression, hemodialysis patients.[2]

Pathophysiology

Endothelial injury allows for either direct infection by virulent organisms or the development of uninfected platelet-fibrin thrombus which becomes a nidus for transient bacteremia, except in the case of S. aureus, which can infect intact endothelium. These organisms enter the bloodstream from the skin, mucosal surfaces or previously infected sites and adhere to nonbacterial thrombus due to valvular damage or turbulent blood flow. In the absence of host defenses, this organism is allowed to proliferate forming small colonies and shed in the bloodstream. Left-sided infection is much more common than right-sided infection, except among intravenous drug users.[3]

History and Physical

Fever is the most common symptom. It can be associated with chills, night sweats, anorexia, weight loss, loss of appetite, malaise, headache, myalgias, arthralgias, abdominal pain, dyspnea, cough, and pleuritic pain.

Cardiac murmurs are observed in about 85% of patients. Congestive heart failure develops in 30% to 40% of patients usually due to valvular dysfunction. Other signs include cutaneous manifestations such as petechiae or splinter hemorrhages (non-blanching linear reddish-brown lesions under the nail bed).

Complications include conduction disease (first-degree atrioventricular block, bundle branch block, or complete heart block), ischemia (emboli to the coronary arteries), embolic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, brain abscess, septic emboli leading to infarction of the kidneys, spleen, lungs and other organs, hematogenous spread of infection leading to vertebral osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, or psoas abscess and systemic immune reaction such as glomerulonephritis.[4]

Evaluation

Definite Infective Endocarditis

Pathologic criteria: Pathologic lesions such as vegetation or intracardiac abscess demonstrating active endocarditis on histology or microorganisms demonstrated by culture or histology of vegetation or intracardiac abscess

Clinical criteria: Two major clinical criteria or one major and three minor clinical criteria or five minor clinical criteria

Possible infective Endocarditis

One major and one minor clinical criteria or the presence of three minor clinical criteria

Rejected Diagnosis of Infective Endocarditis

If an alternate diagnosis is established, if there is the resolution of clinical manifestations with less than or equal to 4 days of antibiotic therapy, if there is no pathological evidence of infective endocarditis found at surgery or autopsy after antibiotic therapy for enterococci 4 days, or if clinical criteria for possible or definite infective endocarditis is not met

Major Clinical Criteria:

Positive blood cultures (one of the following):

- Typical microorganisms for infective endocarditis from two separate blood cultures (S. aureus, Viridans streptococci, Streptococcus gallolyticus, HACEK group), or community-acquired enterococci in the absence of a primary focus) OR

- Persistently positive blood culture with organisms that are typical causes of endocarditis from blood cultures drawn greater than 12 hours apart or all of three or a majority of equal to or greater than 4 separate blood cultures for organisms that are more common skin contaminants OR

- Single positive blood culture for Coxiella burnetii or phase I IgG antibody titer greater than 1:800[5][3]

Evidence of endocardial involvement (one of the following):

- Echocardiography positive for oscillating intracardiac mass on a valve or supporting structures or in the path of regurgitant jets, or on implanted material, in the absence of an alternative anatomic explanation or abscess or new partial dehiscence of prosthetic valve

- New valvular regurgitation

Minor Clinical Criteria:

- Predisposition: Intravenous drug use or presence of a predisposing heart condition

- Fever: Temperature greater than or equal to 38.0 C (100.4 F)

- Vascular phenomena: Major arterial emboli, septic pulmonary infarcts, mycotic aneurysm, intracranial hemorrhage, conjunctival hemorrhages, or Janeway lesions (non-tender erythematous macules on the palms and soles)

- Immunologic phenomena: Glomerulonephritis, Osler nodes (tender subcutaneous violaceous nodules mostly on the pads of the fingers and toes, which may also occur on the thenar and hypothenar eminences), Roth spots (exudative, edematous hemorrhagic lesions of the retina with pale centers), or rheumatoid factor

- Microbiologic evidence: Positive blood cultures not meeting major criterion or serologic evidence of active infection with organism consistent with infective endocarditis[5][3]

Blood Cultures

At least three sets of blood cultures, separated from one another by at least 1 hour, should be obtained from separate venipuncture sites before initiation of antibiotic therapy. If cultures remain negative after 48 to 72 hours, two or three additional blood cultures should be obtained.

Culture-negative endocarditis is defined as endocarditis with no definitive microbiologic etiology after at least three independently obtained blood cultures. Up to 14% of patients may have negative blood cultures due to previous antibiotics therapy or due to fastidious organisms such as Coxiella, Legionella, Bartonella, Mycoplasma, Brucella, Chlamydia, and fungi.

Diagnostic Imaging

Echocardiography should be performed in all patients with suspected bacterial endocarditis. In general, transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is the first diagnostic test; however, transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) has higher sensitivity than TTE and is better for detection of cardiac complications such as abscess, leaflet perforation, and pseudoaneurysm. TTE is inadequate for detecting small vegetations (less than 2 mm), evaluating prosthetic valves and may be technically inadequate due to lung disease or body habitus.

Patients with a negative TEE for whom the clinical suspicion for IE is high should undergo repeat TEE 7 to 10 days later. Repeat TEE is also warranted after an initial positive TEE if clinical features suggest the new development of an intracardiac complication.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory data are usually nonspecific. Positive findings may include elevated inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate and/or elevated C-reactive protein), normochromic-normocytic anemia, positive rheumatoid factor, hypergammaglobulinemia, cryoglobulinemia, circulating immune complexes, hypocomplementemia, and false-positive serologic tests for syphilis. Urinalysis may demonstrate proteinuria, microscopic hematuria, and/or pyuria.[5]

Treatment / Management

Empiric antibiotic therapy should cover Staphylococcus (methicillin-susceptible and resistant), Streptococcus, and Enterococcus. Initial treatment with vancomycin and gentamicin should cover a number of organisms prior to the results of blood cultures.

The duration of therapy depends on the pathogen and site of valvular infection. The duration of therapy should be counted from the first day of negative blood cultures. Most patients are treated parenterally with regimens for up to 6 weeks.

Patients with relapse of native valve endocarditis following completion of appropriate antimicrobial therapy should receive a repeat course of antibiotics.[6][7][8]

Treatment of specific organisms:

- Methicillin-sensitive S. aureus: nafcillin or oxacillin

If nonsevere penicillin allergy: cefazolin

If severe penicillin allergy: vancomycin and daptomycin

If penicillin-resistant: penicillin G for four weeks plus gentamicin for the first two weeks.

Penicillin allergy: vancomycin

Penicillin allergy: vancomycin

Penicillin allergy: vancomycin plus gentamicin for 6 weeks.

Differential Diagnosis

- Antiphospholipid syndrome

- Connective tissue disease

- Intraabdominal infections

- Physical medicine and rehabilitation for systemic lupus erythematosus

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of bacterial endocarditis is with an interprofessional team that includes an infectious disease expert, cardiologist, cardiac surgeon, internist, nurse practitioner, and the primary care provider. Once the diagnosis is made the treatment depends on the status of the valve.

Empiric antibiotic therapy should cover Staphylococcus (methicillin-susceptible and resistant), Streptococcus, and Enterococcus. Initial treatment with vancomycin and gentamicin should cover a number of organisms prior to the results of blood cultures.

The duration of therapy depends on the pathogen and site of valvular infection. The duration of therapy should be counted from the first day of negative blood cultures. Most patients are treated parenterally with regimens for up to 6 weeks.

Patients with relapse of native valve endocarditis following completion of appropriate antimicrobial therapy should be considered for surgery.[6][7][8] The prognosis for patients with bacterial endocarditis depends on the age, number of valves infected, comorbidity, number of other organs affected and any neurological deficit.[9][10]