Continuing Education Activity

Cervical disc herniation is a common cause of neck pain in adults. The severity of the disease can range from mild to severe, and even life-threatening. This activity outlines the etiology, evaluation, treatment, and complications from cervical disc herniations, as well as highlighting the role of interprofessional teams in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology and epidemiology of cervical disc herniations.

- Review the evaluation of cervical disc herniations.

- Outline the treatment and management options available for cervical disc herniations.

- Summarize interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance and improve the outcomes of patients with cervical disc herniations.

Introduction

Vertebrae, along with intervertebral discs, form the vertebral column, or spine. It extends from the base of the skull to the coccyx and includes the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral regions. The spine has several significant roles in the body that include: protection of the spinal cord and branching spinal nerves, structural support, and allows for flexibility and mobility of the body. The intervertebral discs are cartilaginous structures between adjacent vertebrae that support the spine by acting as shock-absorbing cushions to the axial loading of the body.[1][2]

The cervical spine has seven vertebral bodies, numbered C1 to C7, counting from the base of the skull to the thoracic spine. The structure of C1, C2, and C7 have distinctive properties that make them unique in comparison to the typical cervical vertebrae, C3 to C6. The anatomy of C3 to C6 consists of a vertebral body, a vertebral arch, as well as seven processes. The vertebral arch is comprised of the pedicles, bony processes that project posteriorly from the vertebral body, and the lamina; these are the bone segments that form most of the arch. Together, the pedicles and the lamina form a ring around the spinal canal, which harbors the spinal cord. Completing the typical vertebra are seven processes, and they include two superior articular facets, two inferior articular facets, one spinous process, and two transverse processes that allow the passage of the vertebral vasculature.

There are three atypical vertebrae in the cervical region. C1 (atlas) articulates with the base of the skull and is unique in that it does not contain a body due to fusion with the C2 (axis) vertebrae, acting as a pivot point for the atlas to rotate. The most distinctive feature of the C2 vertebra is the presence of an odontoid process (dens) that rises from the superior aspect of its body and articulates with the posterior surface of the anterior arch of C1. C7 has two distinct features that make it unique to a typical cervical vertebra: first, the vertebral vasculature does not traverse through its transverse foramina, and second, it contains along the spinous process, making C7 to be commonly known as "vertebra prominens."[3]

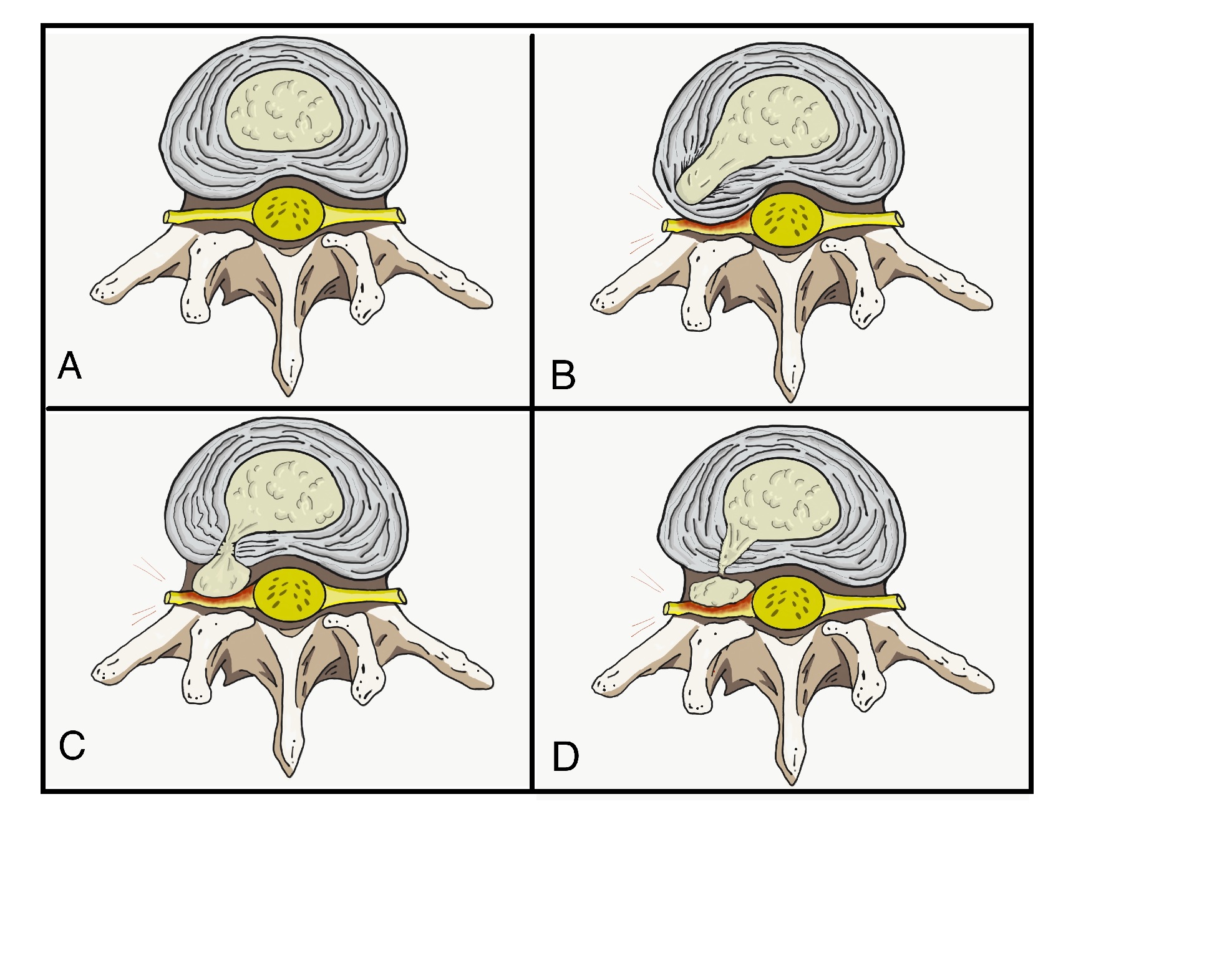

While there are seven cervical vertebrae, there are eight pairs of cervical nerves, numbered C1 to C8. Each pair of cervical nerves emerge from the spinal cord superior to their corresponding vertebra, except for C8, which exits inferiorly to the C7 vertebra.[4] Cervical disc herniation is the result of the displacement of the nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral disc, which may result in impingement of these traversing nerves as they exit the neural foramen or directly compressing the spinal cord contained within the spinal canal.

Etiology

An intervertebral disc is a cartilaginous structure composed of three components: an inner nucleus pulposus, outer annulus fibrosus, and endplates that anchor the discs to adjacent vertebrae. Disc herniations occur when part or all of the nucleus pulposus protrudes through the annulus fibrosus. This process can occur acutely or more chronically. Chronic herniations occur when the intervertebral disc becomes degenerated and desiccated as part of the natural aging process; this typically results in symptoms of insidious or gradual onset that tend to be less severe. In contrast, acute herniations generally are the result of trauma, resulting in the nucleus pulposus extruding through a defect in the annulus fibrosus. This injury will usually result in a sudden onset of more severe symptoms when compared to chronic herniations.[5]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of cervical disc herniation increases with age for both men and women and is most common in people in their third to fifth decades of life. It occurs more frequently in females, accounting for more than 60% of cases. For both sexes, the most frequently diagnosed patients were in the age group of 51 to 60.[6][7]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of herniated discs is thought to be a combination of mechanical compression of the nerve by the bulging nucleus pulposus and a local increase in inflammatory cytokines. Compressive forces can result in varying degrees of microvascular damage, which can range from mild compression producing obstruction of venous flow that causes congestion and edema, to severe compression, which can result in arterial ischemia. Herniated disc material and nerve irritation may induce the production of inflammatory cytokines, which can include: interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6, substance P, bradykinin, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and prostaglandins. There may even be an additional role that stretching on the nerve root plays in the reproduction of symptoms. The trajectory of the cervical nerve as it exits the neural foramen makes it susceptible to stretch, in addition to compression from a herniation. This arrangement could, in part, explain why certain patients experience pain relief from the abduction of the arm, which presumably decreases the amount of stretch the nerve experiences.[8][9]

Herniations are more likely to occur posterolaterally, where the annulus fibrosus is thinner and lacks the structural support from the posterior longitudinal ligament. Due to the proximity of the herniation to the traversing cervical nerve root, a herniation that compresses the cervical root as it exits can result in radiculopathy in the associated dermatome.[10]

History and Physical

History

Cervical disc herniations most commonly occur between C5-C6 and C6-C7 vertebral bodies. This, in turn, will cause symptoms at C6 and C7, respectively. History in these patients should include the chief complaint, onset of symptoms, alleviating and aggravating factors, radicular symptoms, and any past treatments. The most common subjective complaints are axial neck pain and ipsilateral arm pain or paresthesias in the associated dermatomal distribution.

As part of the evaluation of neck pain, it is important to identify certain red flags that could be features of underlying inflammatory conditions, malignancy, or infection.[11] These include:

- Fever, chills

- Night sweats

- Unexplained weight loss

- History of inflammatory arthritis, malignancy, systemic infection, tuberculosis, HIV, immunosuppression, or drug use

- Unrelenting pain

- Point tenderness over a vertebral body

- Cervical lymphadenopathy

Physical Examination

The clinician should assess the patient’s range of motion (ROM), as this can indicate the severity of pain and degeneration. A thorough neurological examination is necessary to evaluate sensory disturbances, motor weakness, and deep tendon reflex abnormalities. Careful attention should also focus on any sign of spinal cord dysfunction.

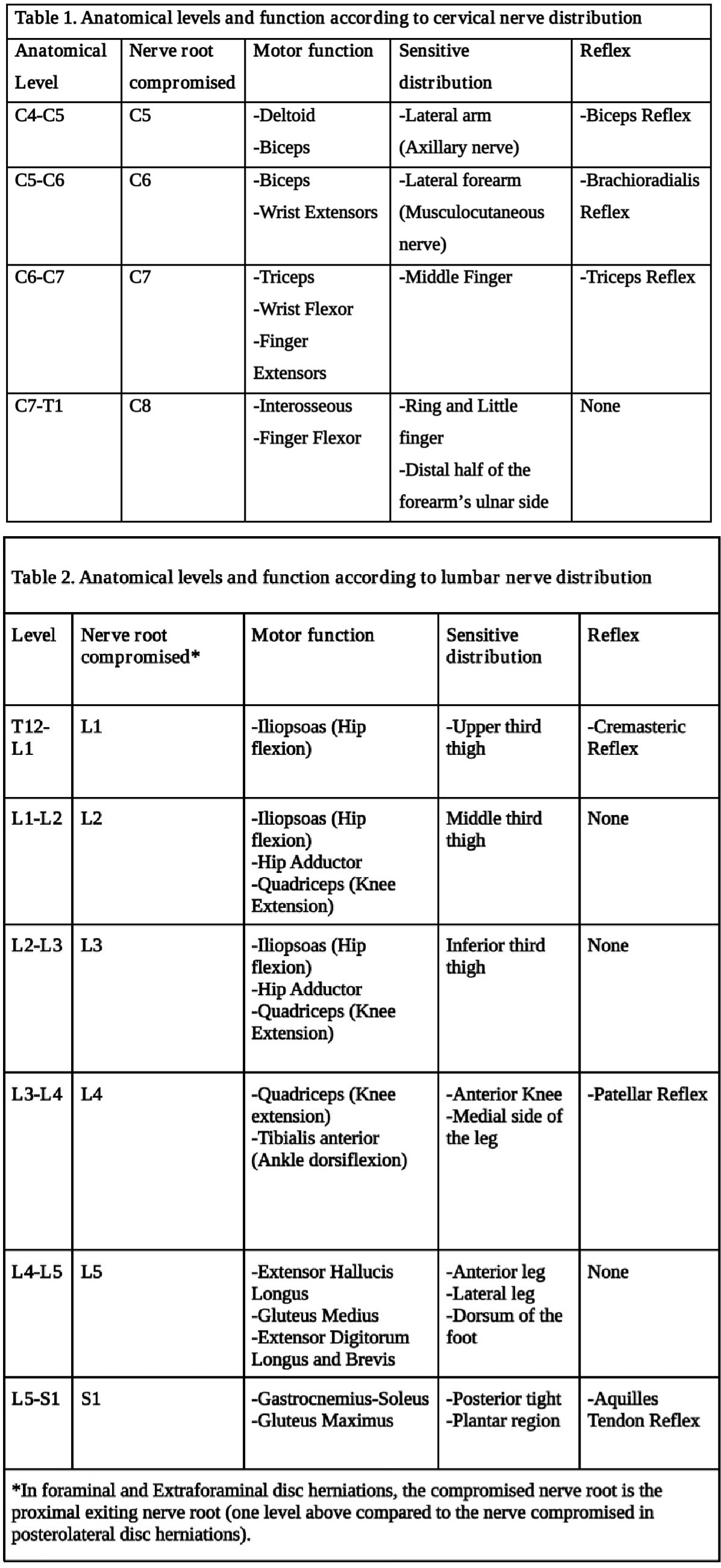

Table 1: Typical findings of solitary nerve lesions due to compression by a herniated disc in the cervical spine

- C2 Nerve – eye or ear pain, headache. History of rheumatoid arthritis or atlantoaxial instability

- C3, C4 Nerve – vague neck, and trapezial tenderness, and muscle spasms

- C5 Nerve – neck, shoulder, and scapula pain. Lateral arm paresthesia. Primary motions affected include shoulder abduction and elbow flexion. May also observe weakness with shoulder flexion, external rotation, and forearm supination. Diminished biceps reflex.

- C6 Nerve – neck, shoulder, and scapula pain. Paresthesia of the lateral forearm, lateral hand, and lateral two digits. Primary motions affected include elbow flexion and wrist extension. May also observe weakness with shoulder abduction, external rotation, and forearm supination and pronation — diminished brachioradialis reflex.

- C7 Nerve – neck and shoulder pain. Paresthesia of the posterior forearm and third digit. Primary motions affected include elbow extension and wrist flexion. Diminished triceps reflex

- C8 Nerve – neck and shoulder pain. Paresthesia of the medial forearm, medial hand, and medial two digits. Weakness during finger flexion, handgrip, and thumb extension.

- T1 Nerve – Neck and shoulder pain. Paresthesia of the medial forearm. A weakness of finger abduction and adduction.[10]

Provocative tests include the Spurling test, Hoffman test, and Lhermitte sign. Spurling test can help diagnose acute radiculopathy. This test is performed by maximally extending the neck and rotating towards the involved side while compressing the head to load the cervical spine axially. This will narrow the neuroforamen and may reproduce symptoms of radiculopathy. Hoffman test and Lhermitte sign can be used to assess for the presence of spinal cord compression and myelopathy. The Hoffman test is performed by holding the long finger and flicking the distal tip downward. A positive sign results when there are flexion and adduction of the thumb. The Lhermitte sign is performed by flexing the patient’s neck, which may result in an electrical sensation traveling down the spine and into the extremities.[8][12]

Evaluation

Most cases of acute spinal injury or herniation will resolve within the first four weeks, without any intervention. The use of imaging during this period is typically not recommended as management of these cases will usually not be altered. Imaging during this period is a recommendation when there is clinical suspicion of potentially serious pathology or in the presence of neurological compromise. Additionally, patients that fail to respond to conservative treatment after a period of 4 to 6 weeks warrant further evaluation.[13] Also, patients that exhibit red flag symptoms listed above may warrant evaluation with lab markers. These can include:

Lab values:

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP): These are inflammatory markers that should be obtained If a chronic inflammatory condition is suspected (rheumatoid arthritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, seronegative spondyloarthropathy). These can also be beneficial if an infectious etiology is suspected.

- Complete blood count (CBC) with differential: Useful to obtain in instances when infection or malignancy is suspected.

X-rays: The first test typically performed and one that is very accessible at most clinics and outpatient offices. Three views (AP, lateral, and oblique) views help assess the overall alignment of the spine as well as for the presence of any degenerative or spondylotic changes. These can be further supplemented with lateral flexion and extension views to assess for the presence of instability. If imaging demonstrates an acute fracture, this requires additional investigation using a computed tomogram (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). If there is a concern for atlantoaxial instability, the open mouth (odontoid) view may assist in diagnosis.

CT Scan: This imaging is the most sensitive test to examine the bony structures of the spine. It can also show calcified herniated discs or any insidious process that may result in bony loss or destruction. In patients that are unable to or are otherwise ineligible to undergo an MRI, CT myelography can be used as an alternative to visualize a herniated disc.

MRI: The preferred imaging modality and the most sensitive study to visualize a herniated disc, as it has the most significant ability to demonstrate soft-tissue structures and the nerve as it exits the foramen.

Electrodiagnostic testing (Electromyography and nerve conduction studies) can be an option in patients that demonstrate equivocal symptoms or imaging findings as well as to rule out the presence of a peripheral mononeuropathy. The sensitivity of detecting cervical radiculopathy with electrodiagnostic testing ranges from 50% to 71%.[14]

Treatment / Management

Conservative Treatments: Acute cervical radiculopathies secondary to a herniated disc are typically managed with non-surgical treatments as the majority of patients (75 to 90%) will improve. Modalities that can be used include[5][8][15]:

- Collar Immobilization: In patients with acute neck pain, a short course (approximately one week) of collar immobilization may be beneficial during the acute inflammatory period.

- Traction: May be beneficial in reducing the radicular symptoms associated with disc herniations. Theoretically, traction would widen the neuroforamen and relieve the stress placed on the affected nerve, which, in turn, would result in the improvement of symptoms. This therapy involves placing approximately 8 to 12 lbs of traction at an angle of approximately 24 degrees of neck flexion over a period of 15 to 20 minutes.

- Pharmacotherapy: There is no evidence to demonstrate the efficacy of non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) in the treatment of cervical radiculopathy. However, they are commonly used and can be beneficial for some patients. The use of COX-1 versus COX-2 inhibitors does not alter the analgesic effect, but there may be decreased gastrointestinal toxicity with the use of COX-2 inhibitors. Clinicians can consider steroidal anti-inflammatories (typically in the form of prednisone) in severe acute pain for a short period. A typical regimen is prednisone 60 to 80 mg/day for five days, which can then be slowly tapered off over the following 5 m to 14 days. Another regimen involves a prepackaged tapered dose of Methylprednisolone that tapers from 24 mg to 0 mg over 7 days. Opioid medications are typically avoided as there is no evidence to support their use, and they carry a higher side effect profile. If muscle spasms are prominent, the addition of a muscle relaxant may merit consideration for a short period. For example, cyclobenzaprine is an option at a dose of 5 mg taken orally three times daily. Antidepressants (amitriptyline) and anticonvulsants (gabapentin and pregabalin) have been used to treat neuropathic pain, and they can provide a moderate analgesic effect.

- Physical Therapy: Commonly prescribed after a short period of rest and immobilization. Modalities include range of motion exercises, strengthening exercises, ice, heat, ultrasound, and electrical stimulation therapy. Despite their frequent use, no evidence demonstrates their efficacy over placebo. However, there is no proven harm, and with a possible benefit, their use is recommended in the absence of myelopathy.

- Cervical Manipulation: There is limited evidence suggesting that cervical manipulation may provide short-term benefits for neck pain and cervicogenic headaches. Complications from manipulation are rare and can include worsening radiculopathy, myelopathy, spinal cord injury, and vertebral artery injury. These complications occur ranging from 5 to 10 per 10 million manipulations.

Interventional Treatments: Spinal steroid injections are a common alternative to surgery. Perineural injections (translaminar and transforaminal epidurals, selective nerve root blocks) are an option with pathological confirmation by MRI. These procedures should take place under radiologic guidance.[15] In the past few years, neuromodulation techniques have been used to a large extent to manage radicular pain secondary to disc herniations.[16] These neuromodulatory techniques consist mainly of a spinal cord stimulation device[17] and an intrathecal pain pump.[18] For patients who are not candidates for surgical intervention, these devices offer minimally invasive efficacious treatment options.

Surgical Treatments: Indications for surgical intervention include severe or progressive neurological compromise and significant pain that is refractory to non-operative measures. There are several techniques described based on pathology. The gold standard remains the anterior cervical discectomy with fusion, as it allows the removal of the pathology and prevention of recurrent neural compression by performing a fusion. A posterior laminoforaminotomy can be a consideration in patients with anterolateral herniations. Total disc replacement is an emerging treatment modality, where indications remain controversial.[8]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses include:

- Brachial plexus injury

- Degenerative cervical spondylosis

- Muscle strain

- Parsonage-Turner syndrome

- Peripheral nerve entrapment

- Tendinopathies of the shoulder

Prognosis

Pain, restricted motion, and radiculopathy that result from a herniated disc typically subside on their own over six weeks in the majority of patients; this is due to enzymatic resorption or phagocytosis of the extruded disc material. There may also be a change in the hydration of the extruded material or a decrease in the local edema, resulting in pain reduction and restoration of function.

In approximately one-third of patients, symptoms will remain persistent despite non-operative intervention. If symptoms last longer than six weeks, it becomes less likely that symptoms will improve without the need for surgical intervention.[15][19]

Complications

Complications from steroid injections are typically mild and range between 3% to 35% of cases. Other, more serious complications can include[5]:

- Nerve injury

- Infection

- Epidural hematoma

- Epidural abscess

- Spinal cord infarction

Complications from surgical intervention include[20]:

- Infection

- Recurrent laryngeal, superior laryngeal, and hypoglossal nerve injuries

- Esophageal injury

- Vertebral and carotid injuries

- Dysphagia

- Horner syndrome

- Pseudoarthrosis

- Adjacent segment degeneration

Deterrence and Patient Education

Educational resources are essential for health care providers, patients, and the public in general to provide the best possible outcomes. These resources include:

- American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons

- American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitations

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Neck pain is a frequently encountered complaint in any primary care or subspecialty practice. The differential diagnoses are broad, and disc herniations often occur concurrently with other cervical pathology. It is imperative to obtain a thorough history, to include prior treatment modalities. A detailed physical exam, with a focus on the neurological exam, will help guide the clinician in determining the severity of the pathology and the need for immediate or delayed evaluation.

The management of patients with cervical disc herniations can be complex and involves a broad interprofessional team approach that can include nurse practitioners, primary care physicians, emergency physicians, orthopedic and neurosurgeons, radiologists, pain specialists, chiropractors, physical therapists, and pharmacists. Most cases will resolve on their own within several weeks, without any specific treatment. If symptoms remain persistent, conservative therapy (NSAIDs, physical therapy) can be initiated and can be successful in a subset of patients. The pharmacist should counsel the patient regarding medications available for pain management and their adverse effects and work with the clinician to assure that side effects are minimized and if opioids are prescribed, their use is carefully monitored by the team. If the pain is intense, referral to a pain specialist may be necessary. Nurses should encourage patients to enroll in a rehab program to strengthen the neck muscles and improve joint flexibility. Nurses should keep in touch with any physical therapy and update the interprofessional team on the progress (or lack thereof) reported by the therapist.

If conservative therapy fails or severe neurological compromise is present, a referral to a surgeon is the next step. There is moderate evidence regarding the effectiveness of some surgical interventions.[21] [Level 1]

Only through close communication between members of the interprofessional healthcare team can outcomes be improved in patients with cervical disc disease. [Level V]