Continuing Education Activity

Supravalvular aortic stenosis (SVAS) is a congenital heart defect that accounts for 8 to 14 percent of all cases of congenital aortic stenosis. It involves a narrowing of the portion of the aorta located just above the aortic valve. The three types of SVAS that have been recognized are hourglass, membranous, and hypoplasia of the aortic arch. This activity describes the evaluation, diagnosis, and management of supravalvular aortic stenosis and highlights the role of team-based interprofessional care for affected patients.

Objectives:

- Describe the epidemiology of supravalvular aortic stenosis.

- Outline exam findings consistent with supravalvular aortic stenosis.

- Identify treatment considerations for patients with supravalvular aortic stenosis.

- Summarize interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to enhance outcomes for patients affected by supravalvular aortic stenosis.

Introduction

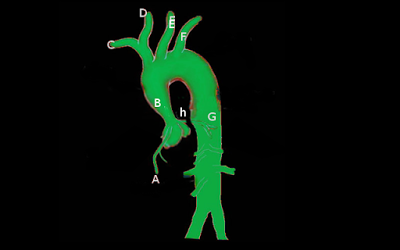

Supravalvular aortic stenosis(SVAS) is a congenital heart defect. As the name suggests, SVAS means the section of the aorta located just above the aortic valve is narrowed. SVAS accounts for 8% to 14% of all congenital aortic stenosis. Three different types of SVAS are recognized: hourglass, membranous, and hypoplasia of aortic arch. Hourglass type SVAS is the most common. Membranous type is the result of the fibrous and/or fibromuscular semicircular diaphragm with a small central opening stretched across the aortic lumen. Diffuse hypoplasia of the ascending aorta is the third.[1][2][3][4]

Etiology

SVAS is seen in syndromic as well as nonsyndromic patients. Williams syndrome, also known as Williams-Beuren syndrome, has autosomal dominant inheritance. Most cases are due to a mutation on chromosome 7q11.23. Nonfamilial forms of SVAS are caused either by mutations in or, in Williams syndrome, deletion of the elastin gene located on chromosome 7q11.23. The deletion in Williams syndrome includes genes other than the elastin gene such as the LIM-kinase gene which is thought to be responsible for the defects in visuospatial cognition that are responsible for the other manifestations of the disease. A rare autosomal dominant disorder such as homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) also has SVAS.[5][6]

Epidemiology

The incidence of congenital heart defects is approximately 8 per 1000 live births. Left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstructive lesions account for approximately 6% of congenital heart disease. SVAS accounts for less than 0.05% of all congenital heart defects. SVAS accounts for 8% to 14% of all congenital aortic stenosis. The sporadic form of SVAS is a more common than the autosomal dominant form.

Pathophysiology

The genetic defect for SVAS is located in the same chromosomal subunit as elastin on chromosome 7q11.23. Elastin is an important component of the arterial wall, but precisely how mutations in elastin genes cause the phenotypes of supravalvular aortic stenosis is not known.[7]

History and Physical

The clinical picture of SVAS differs from other forms of aortic stenosis. SVAS is commonly a congenital malformation seen with Williams syndrome, which is a multisystem disorder with cardiac features of SVAS, infantile hypercalcemia, and deranged vitamin D metabolism. Infants with Williams syndrome often exhibit failure to thrive, due to feeding difficulties, and gastrointestinal problems such as vomiting and constipation. Other clinical manifestations include mild intellectual delay, “cocktail party” personality, elf-like facies, high prominent forehead, stellate or lacy iris patterns, epicanthal folds, strabismus, low flat nasal bridge, upturned nose, smooth philtrum, overhanging upper lip, and wide-spaced teeth. They also can have cardiac manifestations such as narrowing of peripheral systemic and pulmonary arteries and strabismus.

Recognition of this appearance in infancy should alert the physician of the underlying multisystem disease. SVAS in Williams syndrome is usually progressive, with an increase in the severity of obstruction, usually related to the poor growth of the ascending aorta.

Physical findings are very similar such as aortic valve stenosis with exceptions such as accentuation of aortic valve closure, an absent ejection click, and absence of transmission of a thrill and murmur into the jugular notch and along the carotid vessels. Another classical finding of SVAS is that systolic pressure in the right arm is usually higher than that in the left arm. This pulse disparity may be related to the tendency of a jet stream to adhere to a vessel wall and selective streaming of blood into the innominate artery.

Furthermore, SVAS is associated with other cardiac and vascular anomalies which also could complicate the clinical presentation. Some of these anomalies are coarctation of the aorta and ostial stenosis of the carotid, renal, iliac, and other peripheral arteries; dysplasia, thickening and restricted mobility of the aortic valve leaflets; coronary artery stenosis due to focal or diffuse coronary narrowing; and pulmonary artery stenosis.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of SVAS is confirmed by echocardiography. MRI with angiography also provides excellent anatomic detail of SVAS.[4][8]

- Electrocardiography: Left ventricular hypertrophy with strain pattern is usually seen. Biventricular or right ventricular hypertrophy is seen if the pulmonary arteries are also stenosed.

- CXR: Typically, normal with mild to moderate cardiomegaly in some cases depending on the severity of stenosis.

- Echocardiography: Shows the supravalvular stenosis and its type. The sinuses of Valsalva are dilated. The aortic annulus diameter is greater than that of the Sino tubular junction. The ascending aortic arch and the aorta appear to be small or normal in size.

- Doppler examination: Typically overestimates the gradient when compared with that obtained at cardiac catheterization.

- Cardiac angiography: Necessary for accurate measurement of the gradient across the left ventricular outflow tract (and across the stenosis), and to determine the status of the coronary arteries.

Treatment / Management

Surgery usually is performed at gradient levels lower than in valvular aortic stenosis to avoid the progressive obstruction. The indications for surgery is based on expert opinion currently due to limited studies. The likelihood of progression varies with the initial gradient. The risk of progression in adult patients is considerably lower than in childhood.

Surgery is usually curative and is recommended for symptomatic disease with a measured gradient with cardiac angiography of more than 30 mmHg.

Surgical intervention has been successful in most patients with good long-term results. Ross procedure is usually performed, where the diseased aortic valve is replaced with the patient's own pulmonary valve. Sometimes the application of a Y patch and resection with end to end anastomosis have also been successful. Operative risk is higher in patients if there is associated diffuse arteriopathy and biventricular outflow obstruction. Trans-catheter stent placement is another effective alternative, or adjunctive therapy can be used in some patients, especially in those with the involvement of smaller aortic branch vessels.

Differential Diagnosis

Most common differential diagnosis to be considered which have a similar presentation

- Subvalvular aortic stenosis

- Valvular aortic stenosis

- Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy

Prognosis

Outcomes after surgical correction depend on the nature of the stenosis and the presence of associated cardiac lesions. Predictors of worse outcomes and frequent surgical intervention are the presence of diffuse lesions compared to discrete stenosis or presence of associated aortic valve disease.

Pearls and Other Issues

Antibiotic prophylaxis for bacterial endocarditis is not necessary unless the patient has a history of endocarditis. Antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for the first 6 months after the procedure or if there is a residual defect after the 6 months.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of SVAS is with an interprofessional team consisting of a neonatologist, pediatrician, cardiologist, and a cardiac surgeon. Once the diagnosis is made, surgery is necessary. Surgery is usually curative and is recommended for symptomatic disease with a measured gradient with cardiac angiography of more than 30 mmHg.

Surgical intervention has been successful in most patients with good long-term results. Ross procedure is usually performed, where the diseased aortic valve is replaced with the patient's own pulmonary valve. Sometimes the application of a Y patch and resection with end to end anastomosis have also been successful. Operative risk is higher in patients if there is associated diffuse arteriopathy and biventricular outflow obstruction. Trans-catheter stent placement is another effective alternative, or adjunctive therapy can be used in some patients, especially in those with the involvement of smaller aortic branch vessels.

Outcomes after surgical correction depend on the nature of the stenosis and the presence of associated cardiac lesions. Predictors of worse outcomes and frequent surgical intervention are the presence of diffuse lesions compared to discrete stenosis or the presence of associated aortic valve disease.[2][9]