Continuing Education Activity

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL) is a rare primary cutaneous lymphoma that mimics panniculitis and is composed of cytotoxic alpha-beta T-cells. Distinction from the more aggressive primary cutaneous gamma delta T-cell lymphoma was made in the 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Autoimmune diseases occur in approximately 20 percent of cases, and lupus erythematosus panniculitis (LEP) is usually on the differential diagnosis due to its similar clinical and histologic features. This activity reviews how to properly evaluate for subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma and further steps that should be taken when this disease is present. This activity highlights the role of the interprofessional team in caring for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Review the presenting features of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma.

Describe the evaluation of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma.

Explain how to manage subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma.

Summarize the critical role of the interprofessional team in the detection, evaluation, and management of patients with subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma.

Introduction

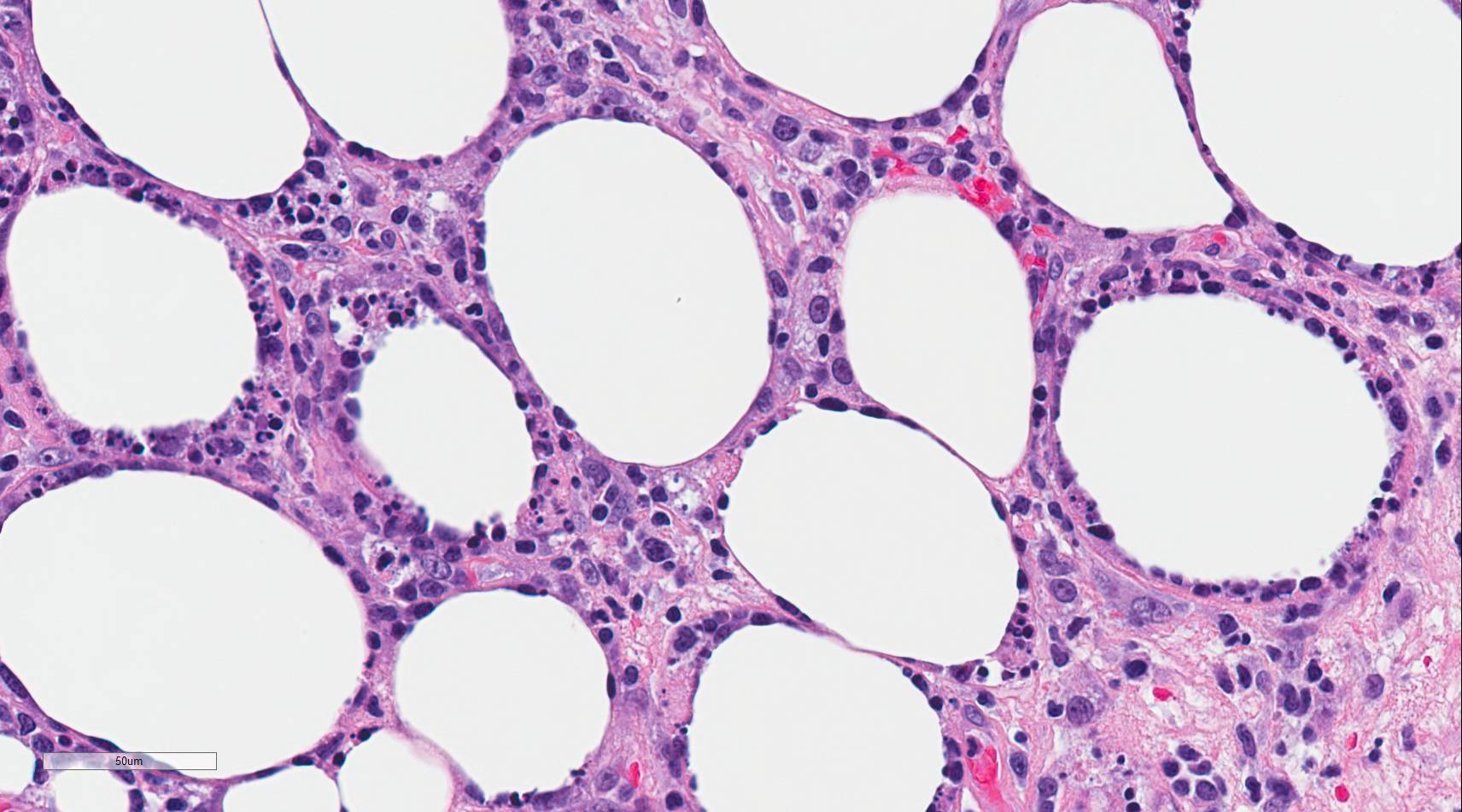

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL) is a rare primary cutaneous lymphoma composed of cytotoxic alpha-beta T-cells that mimics panniculitis.[1] Distinction from the more aggressive primary cutaneous gamma delta T-cell lymphoma was made in the 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues[1]. Autoimmune diseases occur in approximately 20% of cases, and lupus erythematosus panniculitis (LEP) is usually part of the differential diagnosis due to similar clinical and histologic features[2]. Histologically, the neoplastic CD8+, beta F1 expressing cytotoxic T-cells characteristically surround and disrupt individual adipocyte membranes (see Image. Subcutaneous Panniculitis). Most cases have a good prognosis and follow an indolent clinical course; however, 15% to 20% of cases are complicated by hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS)[2][1][3][4].

Etiology

SPTCL is connected with an autoimmune condition in approximately 20% of cases[5]. The incidence of SPTCL in patients with lupus erythematosus and of lupus erythematosus in patients with SPTCL is higher than that of the general population[4]. Considering this association, some investigators have proposed the two entities exist on the same disease spectrum, and cases with overlapping features should be called atypical lymphocytic lobular panniculitis[6][4]. Other explanations include a propensity for patients with one disease to develop the other or misdiagnosis[7]. Further studies need to be done to make any definitive conclusions.

Epidemiology

SPTCL accounts for less than 1% of non-Hodgkin lymphomas and has a slight bias for females. It occurs in both children and adults with an average age of onset of 36 years. [1][2]

Pathophysiology

Migration of the neoplastic T-cells to the adipocyte membrane is postulated to be facilitated by the expression of CCR5 on the neoplastic T-cells. The ligands for CCR5 (CCL3, CCL4, and CCL5) are located on the adipocyte membrane[3].

Histopathology

There is a pattern of lobular panniculitis that typically spares the interlobular septa, epidermis, and dermis. A variably dense infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes(neoplastic T-cells and few reactive B-cells), and macrophages are present. The neoplastic T-cells are atypical with hyperchromatic nuclei and irregular nuclear membranes. By immunohistochemistry, these neoplastic T-cells express CD8, beta F1 and other cytotoxic T-cell markers including granzyme B, perforin, and TIA1. These CD8+ T-cells may be sparse but tend to surround or rim the adipocytes and distort the adipocyte membrane. The neoplastic T-cells directly adjacent to the adipocytes have a higher Ki67 proliferation index compared to LEP, which has a relatively lower Ki67 proliferation index. Karyorrhexis, mitoses, and fat necrosis are commonly seen[1]. Some cases have been documented to have mucin deposition, plasma cell aggregates, vacuolar interface changes, follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy, and periadnexal lymphocytes, making the distinction between SPTCL and LEP difficult at times[8][6][4].

History and Physical

Patients present with multiple subcutaneous plaques and nodules typically on the lower extremities, upper extremities, or trunk [1]. These lesions have overlying erythema, are usually painless, and range in size from 0.5-2.0 cm. There may be lesions in different stages of healing, suggesting a waxing and waning clinical course [5]. In contrast to primary cutaneous gamma delta T-cell lymphoma, ulceration is less common [3].

Systemic symptoms are present in about 50% of cases, including fever, chills weight loss, cytopenias, myalgias, and elevated liver function tests [1]. These symptoms are seen more commonly in patients with concurrent HPS. Lymph node and bone marrow involvement are not usually encountered [3].

Evaluation

The disease is usually confined to the subcutaneous tissue, but rare cases have disseminated to involve the lymph nodes, blood, and bone marrow. Laboratory testing reveals an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein. Cytopenias, elevated liver function tests, and hepatosplenomegaly should prompt close monitoring for the development of HPS. 18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) may help assess the extent of disease upon presentation, response to treatment, and detection of relapses[9][5].

A punch biopsy of the lesion should be submitted for pathologic evaluation, which will allow for assessment of the area of interest. No specific genetic profile has been identified, and the Epstein-Barr virus is usually not present. Clonality of the neoplastic T-cells can be demonstrated by the identification of T-cell receptor rearrangements using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or high throughput sequencing[3]. However, clonality can also be observed in reactive lymphoid infiltrates and certain B-cell lymphomas, so results must be interpreted in the context of the clinical scenario[8][6]. One study found monoclonal T-cell receptor gene rearrangements in 50% of cases[10].

Treatment / Management

Chemotherapy with one or multiple agents was the standard of care when SPTCL and primary cutaneous gamma delta T-cell lymphoma were thought to be the same disease. Disparities in prognosis prompted the distinction of these two entities in the 2008 revision of the WHO. No standard treatment approach currently exists for SPTCL. Studies have shown that most cases are successfully treated with systemic corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents such as etoposide, cyclosporine A, methotrexate, chlorambucil, and bexarotene[3].

Conventional doxorubicin-based chemotherapy may be employed when the disease is progressive[5]. Radiation therapy can lead to long term remissions and may have a role in palliation in patients with localized disease. Stem cell transplants can be performed in refractory or disseminated cases[1][3]. In patients with concurrent HPS, high dose corticosteroids with cyclosporine A or a stem cell transplant with chemotherapy are options[5].

Differential Diagnosis

Lupus erythematosus (LE):

Clinically, LE presents more commonly on the face and proximal extremities, while SPTCL usually shows on the lower extremities, upper extremities, and trunk. Findings such as fever and hepatosplenomegaly may favor SPTCL. However, they can also sometimes be observed in LE.

Histologically, LEP and SPTCL may display many of the same features, most notably involvement of the epidermis. More often, LEP shows interface change, a mixture of CD4 and CD8 T-cells, lymphoid follicles or B-cell aggregates, aggregates of CD123+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells, plasma cell aggregates and intradermal mucin. A low Ki67 proliferation index in the T-cells rimming the adipocytes is another useful feature for distinguishing SPTCL from LEP, as is the lack of cytologically atypical T-cells[8]. Inflammatory cells, such as eosinophils, neutrophils, and plasma cells, are more commonly observed in LE[3]. A synthesis of the clinical features, histology, immunophenotyping, molecular analysis, and possibly repeat biopsies may be needed to differentiate the two entities. Even so, some cases remain ambiguous[11].

Primary cutaneous gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma:

Primary cutaneous gamma delta T-cell lymphoma has a preference for middle-aged adults, and the lesions may be more superficial with surface ulceration[1]. Systemic symptoms and lymphadenopathy are common, with HPS developing in 50% of cases. Histologically, three patterns can be observed: epidermotropic, dermal, and subcutaneous. The subcutaneous pattern can appear similar to the lobular panniculitis seen in SPTCL. However, rimming of the adipocytes is less prominent. By immunohistochemistry, the neoplastic cells are positive for CD56, TCR gamma, TIA1, granzyme B, and perforin and are typically negative for CD4, CD8, and beta F1. Clonal rearrangements of the TRG and TRD genes are present. This entity has a poor prognosis with a five-year survival of 10%.

Extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type: May sometimes present with subcutaneous involvement. In contrast to SPTCL, this entity is positive for EBV[11].

Prognosis

Most cases have an excellent prognosis and follow an indolent clinical course with a 5-year overall survival rate of 85% to 91%[6][5]. HPS occurs in 15% to 20% of cases and portends a worse prognosis. More recently, upper extremity involvement is connected with a worse prognosis[10].

Complications

HPS complicates approximately 20% of cases and carries a 46% 5-year overall survival rate. These patients will require more aggressive treatment[6].

Deterrence and Patient Education

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma is a well-behaving lymphoid neoplasm of the subcutaneous tissue that can be often successfully treated with systemic corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents[3].

Pearls and Other Issues

- Atypical lymphocytes rimming individual fat cells with apoptotic debris is characteristic of SPTCL.

- Neoplastic cells usually express CD8, beta F1, granzyme B, perforin, and TIA1. CD56 and EBV are negative.

- Distinction from lupus panniculitis is difficult.

- TCR rearrangement studies may provide evidence for clonality.

- Final diagnosis often requires clinical correlation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team-best manages this disease. The primary care, nurse practioner, or emergency room physician is often the first to encounter these patients. Prompt referral to an oncologist/hematologist is recommended when lymphoma is suspected. These patients may present with subcutaneous lesions and sometimes symptoms of HPS. A comprehensive patient evaluation, laboratory tests, and punch biopsy help clarify the diagnosis. Treatment most commonly includes immunosuppressive agents or systemic corticosteroids. The oncology nurse and pharmacist should educate the patient on the adverse effects of the chemotherapeutic agents and the duration of therapy. Continued monitoring of blood work is necessary. In addition, patients must be educated on aseptic techniques, hand washing, and avoid crowds during treatment. If HPS is present, treatment will be more aggressive.

With an interprofessional team approach, the 5-year survival exceeds 80%.