Introduction

The larynx is a cartilaginous segment of the respiratory tract located in the anterior aspect of the neck. The primary function of the larynx in humans and other vertebrates is to protect the lower respiratory tract from aspirating food into the trachea while breathing. It also contains the vocal cords and functions as a voice box for producing sounds, i.e., phonation. From a phylogenetic view, the larynx in humans has achieved its highest evolutionary development with the capacity to articulate speech, which is absent in invertebrates and fishes. The larynx is about 4 to 5 cm in length and width, with a slightly shorter anterior-posterior diameter. It is smaller in women than men and larger in adults than children, owing to its growth in puberty. A large larynx correlates with a deeper voice.

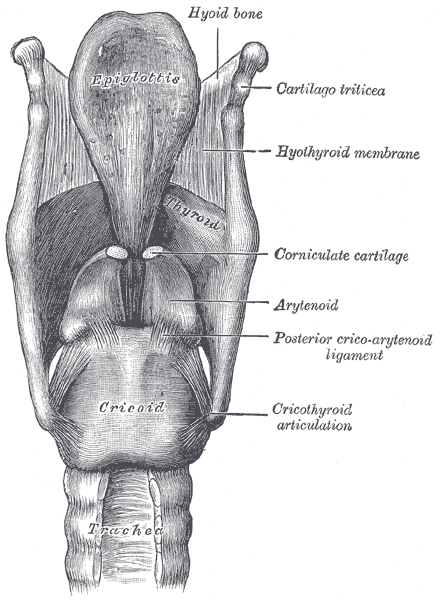

The location of the larynx is at the level of the C3 to C7 vertebrae and is held into position by muscles and ligaments. The superior-most region of the larynx is the epiglottis, which is attached to the hyoid bone connected to the inferior part of the pharynx. The inferior aspect of the larynx connects to the superior region of the trachea.

Structure and Function

The larynx is a cartilaginous skeleton, some ligaments and muscles that move and stabilize it, and a mucous membrane.

The laryngeal skeleton has nine cartilages: the thyroid cartilage, cricoid cartilage, epiglottis, arytenoid cartilage, corniculate cartilage, and cuneiform cartilage. The first three are unpaired cartilages, and the latter three are paired cartilages.

The thyroid cartilage functions as a protective shield surrounding the anterior part of the larynx and spans vertically from the superior to the inferior regions. It is the largest of all six cartilages and has the form of a half-opened book with the back facing the front, with the two halves meeting in the middle, forming a protrusion called the laryngeal prominence, popularly known as Adam’s apple.

The cricoid cartilage is also known as the cricoid ring or signet ring, as it is the only cartilage to encircle the trachea completely. It sits in the inferior part of the larynx, at the level of the C6 vertebra, and has two parts: the anterior part, also called the arch, and the posterior portion, much wider than the anterior, referred to as the lamina.

The epiglottis is an elastic cartilaginous leaf-shaped flap covering the opening of the larynx. It is attached to the internal surface of the thyroid cartilage and projects over the pharynx, allowing the passage of air into the larynx, trachea, and lungs. As the hyoid bone rises, it draws the larynx upwards during swallowing to allow food or drink into the esophagus and to prevent food from entering the trachea.

As for the second set of cartilages, there are three paired cartilages.

Arytenoid cartilages are a pair of small, hard, but flexible pyramid-shaped cartilages that sit over the posterior portion of the cricoid cartilage. The base of each cartilage has two processes: the anterior angle is the vocal process, and the lateral angle is known as the muscular process.

The corniculate cartilages or cartilages of Santorini are small elastic cone-shaped cartilages that articulate with the apices of the arytenoid cartilages.

The cuneiform cartilages, also known as the Wrisberg cartilages, are two elongated fibrous pieces of yellow cartilage placed on either side in the aryepiglottic fold. They have no direct attachment to other cartilages but serve to support the vocal folds and the lateral aspects of the epiglottis.

The laryngeal cartilages move thanks to several joints between them. The cricothyroid joint connects the thyroid cartilage to the cricoid arch. The cricoarytenoid joints connect each arytenoid cartilage to the cricoid cartilage, and the arycorniculate joint connects the arytenoid cartilage to the Santorini cartilage.

Larynx Ligaments

There are two types of ligaments: extrinsic ligaments that attach the larynx to other structures, such as the hyoid or the trachea, and intrinsic ligaments that connect the larynx cartilages between them.

The intrinsic ligaments are the cricothyroid, cricocorniculate, thyroepiglottic, thyroarytenoid, and the arytenoidepiglottic ligaments. The cricothyroid ligament or cricothyroid membrane is pyramid-shaped, with its apex in the middle of the thyroid cartilage and its base in the superior border of the cricoid cartilage. The cricocorniculate ligaments are two fibrous bands linking the cricoid cartilage to the Santorini cartilage. The thyroepiglottic ligament connects the thyroid ligament to the epiglottis. The thyroarytenoid ligaments extend from the external part of the arytenoid cartilages to the middle part of the thyroid cartilage and subdivide into the superior ligament that sits next to superior vocal cords and the inferior ligament that sits on the inferior vocal cords. The arytenoidepiglottic ligaments connect the arytenoid cartilages to the epiglottis.

The extrinsic ligaments are the thyrohyoid, hyoepiglottic, and cricotracheal ligaments. The thyrohyoid ligament or membrane attaches the posterior surface of the body of the hyoid bone and the upper border of the thyroid cartilage. The hyoepiglottic ligament connects the surface of the epiglottis with the upper border of the hyoid bone. The cricotracheal ligament connects the cricoid ligament with the first ring of the trachea.

Laryngeal Cavity

The internal space of the larynx extends along the laryngeal inlet to the lower border of the cricoid cartilage. It is pyramid-shaped, with its superior base pointing to the tongue and its apex to the trachea. It has a base, an apex, and three parts: one posterior and two laterals.

The posterior part of the internal space of the larynx is part of the anterior wall of the pharynx and has two vertical recesses referred to as the piriform sinus. The form of the lateral aspects is determined by the larynx cartilage and consists of three parts: a superior one that matches the thyroid cartilage, an inferior one that matches the cricoid cartilage, and a middle one called the cricothyroid space. The Larynx apex forms a hole that joins to the trachea. The base of the larynx is oval-shaped and communicates with the pharynx.

The internal space of the larynx is wide in the superior and inferior parts but narrows in the middle, forming a section named glottis and dividing all the spaces into three sections: supraglottic, glottis, and infraglottic.

The vocal cords, the glottis, and the larynx ventricles comprise the glottic space.

The vocal cords are four folds of fibro-elastic tissue, two superior and two inferior ones, anteriorly inserted into the thyroid cartilage and posteriorly in the arytenoid cartilage. The superior vocal cords are thin, ribbon-shaped, and have no muscle elements, while inferior vocal cords are wider and have a muscular fascicle covering their entire length. The space between the superior vocal cords is larger than the space between the inferior vocal cords, and viewed from above, four vocal cords are present in the larynx space. The inferior vocal cords are the only ones capable of approaching each other; thus, they are considered to be true vocal folds, while the superior ones are referred to as false vocal cords or folds.

The glottis is the portion of the laryngeal cavity formed by the four vocal folds and the opening between the folds.

The laryngeal ventricles or Morgagni sinus are a fusiform fossa between the inferior (true vocal folds) and the superior vocal cords (vestibular folds).

The subglottic section is the space below the glottis and has an inverted bottleneck shape limited by the vocal cords and the trachea.

The supraglottic section forms an oval cavity, extending along the free edge of the epiglottis and the aryepiglottic folds down to the arytenoid cartilages, the hyoepiglottic ligament is usually considered the roof of this cavity.

Embryology

The first human larynx can be traced to the primitive pharyngeal floor in the first four weeks of intrauterine life as a longitudinal notch, known as the laryngotracheal groove. This groove will eventually form the esophagotracheal septum around the fifth week of embryonic life, with the respiratory system anteriorly and the esophagus lying on the dorsal side.

The connective tissue, smooth muscles, and cartilage that will form the larynx arise from splanchnic mesenchyme located ventral to the foregut. The larynx cartilages develop from the third, fourth, and sixth pharyngeal arches. In this period, primitive glottis has a T-shaped form as a result of some paired arytenoid swellings produced by the proliferation of the mesenchyme, which will reduce the laryngeal lumen to a small opening. The laryngeal epithelium quickly develops, temporarily obliterates the laryngeal lumen, and becomes re-canalized in the tenth week when the epithelium breaks up. The future vocal cords form from a pair of lateral depressions joined to the anterioposterior folds of the mucous membrane.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The blood supply to the larynx comes from the superior and inferior laryngeal arteries. The superior laryngeal artery is a superior thyroid artery branch supplying the epiglottis, supraglottic region, and superior vocal cords. The inferior laryngeal artery is also a branch of the superior thyroid artery and supplies the subglottic region and the inferior vocal cords. The inferior laryngeal artery sometimes has a small branch of the superior thyroid artery supplying the posterior cricoarytenoid and arytenoid muscles.

The laryngeal veins accompany the arteries and take the same names, i.e., the superior and inferior laryngeal veins. These veins drain into superior thyroid and inferior thyroids veins, which drain into internal jugular and subclavian veins, respectively.

Larynx lymph drainage is subdivided into supraglottic and infraglottic lymphatics. The supraglottic lymphatic nodes are very dense and drain into deep cervical lymphatics. The subglottic lymphatics are less dense and drain into the lower deep cervical nodes through pre and paratracheal nodes and prelaryngeal nodes. The vocal folds (glottic region) have no lymphatics.

Nerves

The larynx receives innervation from the inferior laryngeal nerve, the recurrent laryngeal nerve, and the superior laryngeal nerve.

The superior laryngeal nerve is a branch of the vagus nerve (X cranial nerve) arising from the inferior ganglion of the vagus nerve. It also receives branches from the superior cervical ganglion of the sympathetic nervous system and descends between the carotid vessels and pharynx, reaching the larynx just below the hyoid bone, where it divides into two branches, the internal and the external. The external laryngeal nerve supplies the cricothyroid muscle. The internal laryngeal nerve descends to the thyrohyoid membrane along with the superior laryngeal artery, spreading out across the epiglottis and supplying the mucous membrane surrounding the entrance of the larynx.

The inferior laryngeal nerve or recurrent nerve is the principal nerve responsible for the innervation of all intrinsic muscles of the larynx, except for the cricothyroid muscle. The right and left recurrent nerves are not symmetrical.

The left recurrent nerve arises from the vagus nerve bellow into the thorax, looping around the aortic arch (whereas the right recurrent nerve loops around the subclavian artery) and passes upwards to the trachea and esophagus before entering the larynx just posterior to the cricothyroid joint underneath the inferior constrictor muscle.

The right recurrent nerves branch off the vagus in the base of the neck, looping the subclavian artery, go upward lateral to the trachea, and enter the larynx between the cricoid and thyroid cartilages.

Normally, the internal and inferior laryngeal nerves connect in the Galen anastomosis.

Muscles

The laryngeal muscles divide into intrinsic muscles, the primary function of voice production, and extrinsic muscles that move the larynx. We shall proceed to examine the former before the latter.

Intrinsic Muscles

The cricothyroid muscle has two concave surfaces, the superior and inferior; it attaches to the cricoid arch and the lower lamina of the thyroid to the superior belly and the inferior cornu to the inferior belly. These muscles produce elongation of the vocal folds, resulting in higher-pitch phonation.

The posterior cricoarytenoid muscle attaches to the posterior cricoid cartilage to the arytenoid cartilage. These muscles abduct (open) the vocal cords, the opposite action to the lateral cricoarytenoid muscles.

The lateral or anterior cricoarytenoid muscles extend from the lateral cricoid cartilage to the muscular process of the arytenoid cartilage. These muscles adduct the vocal folds, the opposite action to the posterior cricoarytenoid muscles.

The thyroarytenoid muscles arise from the thyroid cartilage and the middle cricothyroid ligaments and insert into the arytenoid cartilage. These muscles relax and approximate the vocal folds.

The aryepiglottic muscles attach to the arytenoid cartilages and extend to the epiglottis. These muscles adduct the aryepiglottic folds.

The arytenoid muscles extend to the transverse and oblique portions between the arytenoid cartilages. The transverse arytenoid muscle is the only impaired intrinsic muscle of the larynx. These muscles adduct the vocal folds.

Extrinsic Muscles

The extrinsic larynx muscles are paired and allow the movement of the larynx.

The thyrohyoid muscle inserts on the thyroid cartilage and the body of the hyoid bone. The receives innervation from the first cervical nerve, along with the hypoglossal nerve. Its primary function is to depress the hyoid bone, thus elevating the larynx.

The sternothyroid muscles are situated beneath the sternohyoideus muscle; they arise from the sternum and first rib, go to the lamina of the thyroid cartilage, and are innervated by the ansa cervicalis. These muscles depress the larynx.

The inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscles extend from the cricoid and thyroid cartilages to the pharyngeal raphe. These muscles are innervated by the vagus nerve via branches of the pharyngeal plexus and recurrent laryngeal nerve and narrow the pharynx diameter to contribute to swallowing.

The stylopharyngeus muscles stretch from the styloid process in the temporal bone to the thyroid cartilage. These muscles receive their nerve supply from the glossopharyngeal nerve, and their function is to elevate the larynx and the pharynx.

The palatopharyngeus muscles stem from the palatine aponeurosis and pterygoid processes and inserts into the thyroid cartilage. They are part of the soft palate and are innervated by the pharyngeal branch, and their action is to elevate the larynx and pharynx.

Other muscles that are not strictly considered laryngeal, as they do not insert in the larynx or any of its parts, may also contribute to the movement of the larynx, such as the geniohyoid, mylohyoid, digastric, or stylohyoid muscles that elevate the larynx, while the omohyoid and sternohyoid muscles cause laryngeal depression.

Physiologic Variants

The larynx is a structure that may exhibit several differences according to gender, which is the primary cause of the voice differences between males and females. Usually, the male larynx is more prominent than in females. Similar gender differences exist in the thyroid, which is thicker in males and has a different angle, 95 degrees in males and about 115 degrees in females.

Laryngeal innervation may also vary from one person to the next. Thus, the recurrent laryngeal nerve has been widely studied, and several variations have been identified. For example, the recurrent laryngeal nerve may divide into two or more branches, and the anterior branch has been documented to enter the larynx anteriorly or posteriorly to the cricothyroid joint. Given that the left recurrent nerve loops around the aortic arch, its course may also vary due to an aortic aneurysm or even aortic variations between individuals. Cases of “non-recurrent” inferior laryngeal nerve have also been studied, with the recurrent laryngeal passing directly to the larynx from the vagus in the neck without looping around the subclavian artery[1].

The relationship that exists between the recurrent laryngeal nerve and the inferior thyroid artery has also generated much scrutiny; usually, the nerve ascends posterior to the artery (about 60%), but occasionally, it may ascend anterior (around 32.5%) or even between the branches of the artery (approximately 6.5%).

The position of the recurrent nerve is very important due to the risk of surgical injury.[2][3][4]

Surgical Considerations

Cricothyrotomy is probably the most extensively used medical technique involving a small incision in the cricothyroid membrane to establish an airway in life-threatening situations. Nevertheless, the most critical surgical consideration of laryngeal surgery is the iatrogenic injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve in thyroid surgery; usually, before and following thyroid surgery, recurrent laryngeal nerve integrity is confirmed by an indirect laryngoscopy. Hence, surgeons rely heavily on intraoperative landmarks to identify and evade the recurrent laryngeal nerve. These landmarks include, but are not restricted to, the ligament of Berry, inferior thyroid artery, and tubercle of Zuckerkandl, among others.[5]

Clinical Significance

Laryngitis

Laryngitis is the inflammation of the larynx. Chronic (over 3 weeks) laryngitis is more common than acute (less than 3 weeks) laryngitis. Symptoms usually are hoarse voice, pain, and coughing; sometimes, depending on the cause, often accompanied by fever.[6]

Most acute cases of laryngitis occur as part of a viral upper respiratory tract infection, although in some cases, it may be due to bacterial infection. Fungal laryngitis is usually underdiagnosed and may account for up to 10% of cases. Excessive use of the vocal folds (eg, singers, teachers, and other professionals) can cause laryngitis/laryngeal trauma.

The most common causes of chronic laryngitis are smoking, allergies, and reflux.

Vocal Fold Paralysis

Vocal fold paralysis (VFP) is a consequence of recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis; this nerve, as told before, innervates all the intrinsic larynx muscles but the cricothyroid muscle. The etiology of recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis includes a wide variety of diseases or disorders/causes.[7]

Congenital VFP may result from an array of diseases such as hydrocephalus, Goldenhar syndrome, and anatomical abnormalities such as tracheoesophageal fistula producing VFP. Though infection is a rare cause of VFP, it is usually owing to viral infection. Trauma, including iatrogenic damage to the nerve, is a common cause of VFP. Thyroid, lung, or esophagus tumors can also produce VFP. Additionally, several systemic neurologic diseases, such as multiple sclerosis or myasthenia gravis, can produce VFP.

Laryngeal Cancer

Usually, laryngeal cancer is a squamous cell carcinoma and originates in the glottis. Signs and symptoms include hoarseness or any voice change (including VFP), lump in the neck, cough, stridor, or difficulty swallowing.[8]