Continuing Education Activity

Neuromas are benign nodular tumors that arise from a nerve. Neuromas are non-neoplastic masses of connective tissue, Schwann cells, and regenerated axons that can develop anywhere in the body. Although there are various types of neuromas, the term most commonly refers to traumatic neuromas, which develop as an injured nerve starts to heal in an uncontrolled manner, resulting in a lump of unorganized axon fibers and non-neural tissue growth. Traumatic neuromas can be caused by any type of nerve injury, including surgical trauma, blunt force trauma, nerve transection, or chronic inflammation. Other neuromas can occur secondary to syndromes (eg, neurofibromatosis) or true neoplastic processes (eg, acoustic neuroma or Morton neuroma).

Diagnosis of traumatic neuromas is initially made by clinical assessment with diagnostic imaging studies performed to evaluate the location and severity of nerve injury. The characteristic clinical presentation consists of a history or source of injury followed by the gradual development of a firm, ovoid palpable mass, typically less than 2 cm in size, with pain symptoms. Traumatic neuroma treatment consists of surgical and nonsurgical management, including physiotherapy, medications, and high-frequency electrical stimulation. This activity for healthcare professionals aims to enhance learners' competence in selecting appropriate diagnostic tests, implementing appropriate management approaches, and fostering effective interprofessional teamwork to improve patient outcomes.

Objectives:

Identify the pathophysiology of neuroma formation and propagation.

Differentiate subtypes associated with neuromas.

Determine primary treatment modalities for traumatic neuromas.

Apply effective strategies to improve care coordination among interprofessional team members to facilitate positive outcomes for patients with traumatic neuromas.

Introduction

Neuromas are benign nodular tumors that arise from a nerve. Neuromas are non-neoplastic masses of connective tissue, Schwann cells, and regenerated axons that can develop anywhere in the body. Although there are various types of neuromas, the term most commonly refers to traumatic neuromas, which develop as an injured nerve starts to heal in an uncontrolled manner, resulting in a lump of unorganized axon fibers and non-neural tissue growth. Traumatic neuromas can be caused by any type of nerve injury, including surgical trauma, blunt force trauma, nerve transection, or chronic inflammation. Traumatic neuromas also can be subtyped further based on whether the nerve segments are connected (ie, neuroma-in-continuity), remain separated (ie, end-neuroma), or are entrapped within scar tissue. Other neuromas can occur secondary to syndromes (eg, neurofibromatosis) or true neoplastic processes (eg, acoustic neuroma or Morton neuroma).[1][2]

Diagnosis of traumatic neuromas is initially made by clinical assessment with diagnostic imaging studies performed to evaluate the location and severity of nerve injury. The characteristic clinical presentation consists of a history or source of injury followed by the gradual development of a firm, ovoid palpable mass, typically less than 2 cm in size, with pain symptoms. The pain caused by neuromas is commonly described as stiffness, hypersensitivity, burning, tingling, or sharpness. Traumatic neuroma treatment consists of surgical and nonsurgical management, including physiotherapy, medications, and high-frequency electrical stimulation. A strong emphasis on prevention, meaning surgical exploration and repair of nerve injuries promptly after the initial injury occurs.[1]

Etiology

Neuromas can be classified as true neoplasms, traumatic neuromas, and neuromas secondary to a genetic syndrome.[3]

Traumatic Neuromas

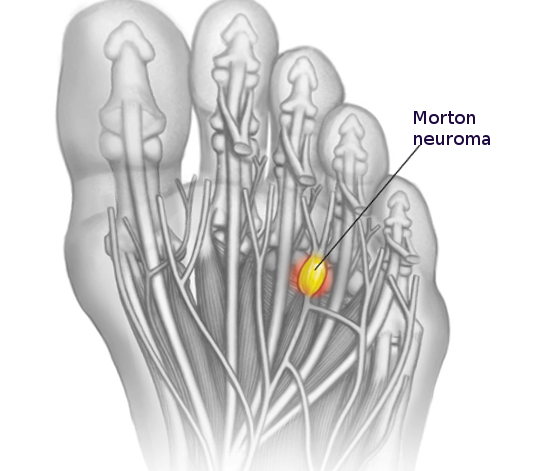

These neuromas arise after blunt or sharp trauma or traction injury. Common traumatic neuromas include localized interdigital neuromas (ie, Morton neuromas), which occur in the third metatarsal interspace, and Pacinian neuromas, which consist entirely or partially of dermal tactile receptors (ie, Pacinian corpuscles). See Image. Morton Neuroma. Elective surgery is also a significant cause of traumatic neuromas. Neuroma formation following elective hand surgery is common, with the superficial radial nerve and the saphenous nerve being especially susceptible. Furthermore, neuromas called stump neuromas can develop after amputation (see Image. Neuroma After Amputation). The symptoms they produce should not be confused with phantom limb pain.[4][1]

True Neoplasms

These types of neuromas are inherited benign nerve-sheath tumors, which include neural fibrolipomas, acoustic neuromas, ganglioneuromas, neurothekeomas, and nerve-sheath myxomas. Neural fibrolipoma is a sausage-shaped localized expansion of epineural adipose and fibrous tissue of a segment of a major nerve. Acoustic neuroma or vestibular schwannoma is an intracranial tumor presenting with tinnitus, hearing loss, and vertigo. Ganglionneuroma is a sympathetic autonomic nervous tumor commonly arising in the abdomen, which can produce hormones. Neurothekeoma and nerve sheath myxoma are both perineural tumors.[3]

Genetic Syndrome Neuromas

These neuromas occur secondary to an underlying genetic syndrome (eg, neurofibromatosis or multiple endocrine neoplasia 2B). Neurofibroma, or neurofibromatosis, is a genetic condition in which numerous neuromas form in various places of the central and peripheral nervous system. They can present as skin lesions, resulting in hearing and balance issues or pain. No cure is known; surgery has a role in symptom control. Multiple endocrine neoplasia 2B is a genetic syndrome consisting of medullary thyroid carcinoma, pheochromocytoma, and mucosal neuromas.

Epidemiology

While the incidence of traumatic neuromas varies in the literature, clinicians should recognize that most neuromas are asymptomatic and, therefore, frequently go undetected. One study on hand injuries found a 1% incidence after nerve repair and 7.8% following finger amputation. Another hand injury study reported an incidence of 6.6% after finger amputation.[5][6]

Pathophysiology

The primary pathophysiology in traumatic neuroma formation is widely accepted to be the injury of the perineurium, which protects the axonal fibers. When the perineurium is damaged, nerve fiber damage and disorganization may occur. Another critical aspect of traumatic neuroma is thought to be neuroinflammation.[7] As the axons reach the extra perineurial space where tissue damage is present, inflammation may also result. The compounds released secondary to inflammation can lead to neuroma formation. The injured nerve endings begin to regenerate unregulated, disrupting the fibers' mostly linear organization, resulting in an unorganized growth. This growth will create and transmit signals the central nervous system interprets as pain.

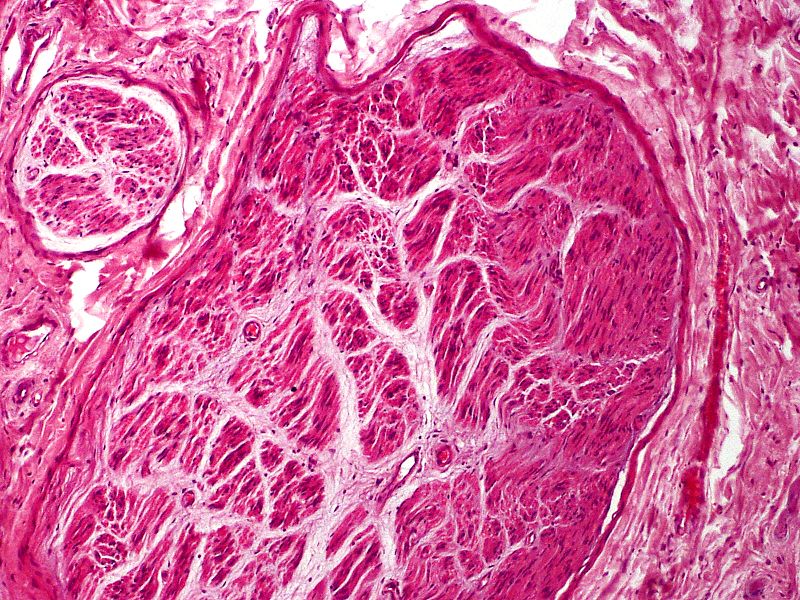

Histopathology

Myofibroblasts are frequently part of the scar, either scattered throughout or in aggregates, mainly present in the 2 to 6 months postinjury. As more collagen is laid down, the number of myofibroblasts diminishes.[8] With standard HE stains, one can observe the irregular axon fascicles surrounded by prominent perineurium in various stages of maturation. Depending on when the sample gets taken, perineurium can also still be damaged. Especially close to the cut nerve endings, Schwann cells, and myofibroblasts can be present within the scar tissue. There is also a relatively high content of glycosaminoglycans (see Image. Traumatic Neuroma).[1][2]

Pacinian corpuscle neuromas are a very rare subtype of neuroma. Pacinian corpuscles are mechanoreceptors in various organs, including the skin, which can develop a neuroma, most frequently in fingers after skin injuries. Pacinian corpuscle neuromas can be easily identified histologically as the corpuscles are larger in size and number than usual.

History and Physical

Diagnosis of traumatic neuromas is initially made by clinical assessment with diagnostic imaging studies performed to evaluate the location and severity of nerve injury. Localization of traumatic neuromas and the extent of structural damage is needed to determine optimal management. Therefore, obtaining a comprehensive history and performing a clinical exam is essential for this initial assessment.[1]

The characteristic clinical presentation consists of a history or source of injury followed by the gradual development of a firm, ovoid palpable mass, typically less than 2 cm in size, with pain symptoms.[1] The history of the trauma should also include where and how the injury was treated and if any attempt was made to repair the nerve. In patients without a history of trauma, the differential should shift toward genetic neuroma causes and true neoplasms. Physical examination typically reveals a well-defined firm palpable nodule, which can adhere to nearby structures. With palpation, patients can experience a sensation similar to electric shock. The pain caused by neuromas is also commonly described as stiffness, hypersensitivity, burning, tingling, or sharpness.[1]

Evaluation

Diagnostic studies are typically performed to localize the traumatic neuroma and evaluate the injury severity. Following clinical assessment, electromyography (EMG) studies are performed to test nerve impairment. Ultrasound (US) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can subsequently be utilized to examine peripheral nerves to determine the location and nature of nerve damage.[1]

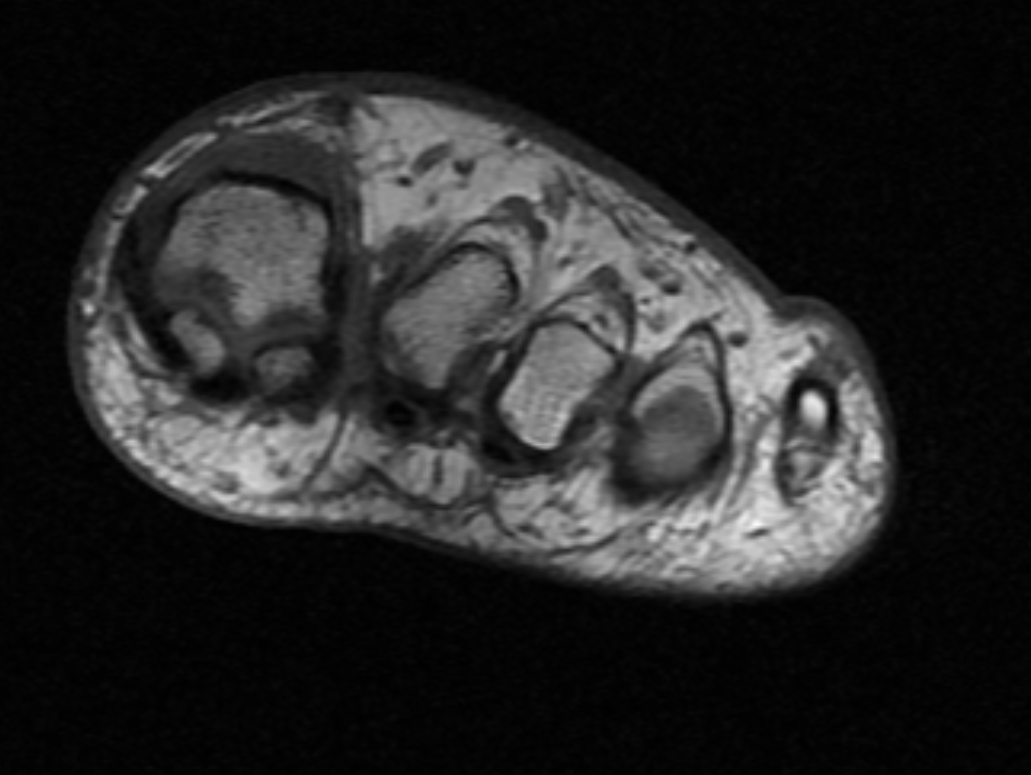

US may be utilized to evaluate nerve continuity and follow-up examinations after treatment. MRI allows greater visualization of peripheral nerves (see Image. MRI Morton Neuroma). Some experts prefer MRI to assess injury as it provides high-resolution images. However, some authorities recommend that both modalities be utilized by performing the initial evaluation with the US followed by an MRI when US visualization is limited or results are discordant with clinical and EMG assessment. Laboratory studies typically do not aid in diagnosis. However, postsurgical histopathology examination of the excised lesion is recommended to exclude malignancy.[1]

Treatment / Management

Traumatic Neuroma Prevention Strategies

Due to the lack of consensus on the optimal management approach for traumatic neuromas, prevention is the primary strategy.[9] Prevention is essential as this condition affects the quality of life. Following injuries or surgeries in which a nerve is transected, the surgeon should reconnect the 2 nerve endings as soon as possible. Following injuries where nerve damage is suspected, patients should be evaluated in centers where specialists, can diagnose, explore, and repair the nerve damage. Many different surgical strategies exist to prevent neuroma formation after trauma which are comparably effective. Neurorrhaphy significantly reduces neuroma formation to 1% from 7.8%.[6] Generally accepted principal surgical aims are that the repair should not be under tension and the nerve should be aligned to reconnect the same axon segments under microscope magnification. Some careful and minimal debridement is acceptable. In damaged axons where a gap is present, a less crucial sensory nerve should be sacrificed to provide a nerve graft for the repair, which can be multi-stranded. For cases such as amputation, where 2 nerve segments cannot be rejoined, burial or suturing of the nerve onto the muscle to help prevent neuroma formation, called targeted muscle reinnervation, is common.[1]

Furthmore, in patients who undergo a neurectomy procedure, some surgical techniques have been found to have a higher risk of neuroma formation. Electrocoagulation or cryoneurolysis are preferred as they have a lower incidence of traumatic neuroma than tight ligation, scissors cut, and CO2 laser transection techniques. The direction in which a nerve is cut has also been shown to affect neuroma formation, with oblique nerve cutting forming neuromas less frequently than perpendicular or transverse cutting.[1]

Nonoperative Treatment

Conservative treatments may be used for symptomatic treatment of traumatic neuromas. Ice packs, elevation, and rest can aid in short-term relief of symptoms if swelling is present. Pharmacological therapies include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), local anesthetic creams or injections, intralesional steroid injections, intralesional phenol, or dehydrated alcohol sclerosing injections. [10] Unfortunately, pain symptoms are often resistant to most pharmacological analgetic methods, with 60% to 70% of patients being unresponsive to symptomatic pain management techniques.[11]

Surgical Treatment

Surgical options are considered when conservative management has been exhausted (see Image. Morton Neuroma Classic Appearance). The most common surgical treatment is a dorsal approach neurectomy, where the affected nerve is excised under tension.[12] This procedure has a high success rate of 70% to 85%. Recurrence rates are reportedly high, though considerable variation is present in the literature, ranging from 15% to 50%.[13][14] The recurrence of neuroma is thought to be due to a nerve regeneration process in an attempt to repair an injury. This rationale has instigated alternative procedures that aim to inhibit recurrence and the formation of a painful stump neuroma, such as target muscle reinnervation (TMR), burying the nerve end into muscle or bone, capping the nerve stump, or using an allograft to reconstruct a nerve defect.[15][16][17][18][11][19][20][12]

In 2022, Thomajan described using a porcine extracellular matrix nerve cap following neuroma excisions with good clinical success. The author suggests utilizing an epineurial anchor suture to secure the matrix in the nerve stump and further burying the nerve stump with the nerve cap into the surrounding muscle.[12] Conversely, if both proximal and distal nerve ends are available, reconstruction of the nerve defect can potentially recover somatic and autonomic function while also restoring sensory signaling. A recent study described the use of processed nerve allograft for intercalary reconstruction with sensory recovery in 88% of patients.[11]

Differential Diagnosis

Other nonneoplastic peripheral nerve tumors include:

- Ganglion cyst

- Intraneural heterotopic ossification

- Sarcoid granuloma

- Inflammatory pseudotumor of nerve

- Leprous neuropathy

- Hypertrophic neuropathy

- Lipofibromatous hamartoma

- Neuromuscular choristoma [21]

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

The current focus is on prevention, and various studies are looking at how to reduce posttraumatic neuroma formation during surgical repair. The CoNNECT randomized trial still in progress is looking at end-to-end, end-to-end plus conduit, and no direct suture, only conduit-secured repairs to determine if tubes are beneficial and if sutureless solutions merit consideration. A study examining a substance that actively decreases neuroma formation when continuously released to the repair site is also underway.[22] A group of Chinese scientists is looking into using autologous vein grafts instead of nerve grafts to bridge short gaps after nerve injury.[23] Work is also being done using stem cells to help nerves regenerate after an injury. Although the main aim is to improve function rather than to reduce neuroma formation.[24]

Prognosis

Early diagnosis and treatment of a nerve injury are crucial for improved outcomes due to the small interval during which successful reinnervation or nerve surgery can be performed. Patients with traumatic neuromas frequently have reduced quality of life due to functional impairment, chronic pain syndrome lasting weeks to years, and mental health issues.[1]

After digital amputation, 6% of people will develop a neuroma.[5] When operated at the time of injury, this can decrease to 1%. Neuromas are a benign condition; however, these tumors can increase in size and pain severity and become tethered to adjacent tissue. No studies are currently looking at traumatic neuroma regression. However, several studies are looking at acoustic neuroma regression rates, which are around 4%, resulting in some patients having active observation rather than surgery.[25]

Complications

A neuroma is a painful condition that is often so severe that patients have to undergo surgery. Complications of surgery are infection, bleeding, scarring, and anesthetic risks. Unfortunately, recurrence rates for traumatic neuromas are high also. Other neuroma complications include functional impairment, chronic pain syndrome lasting weeks to years, and mental health issues.[1]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Dressings are necessary for the wound healing period. Nerve repair occurs without tension; there is usually no need to protect the repair with a rigid brace or plaster, only a bulky dressing.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Due to the lack of consensus on the optimal management approach for traumatic neuromas and the effect these tumors can have on a patient's quality of life, prevention is the primary strategy. (Refer to the Treatment section for more information on Traumatic Neuroma prevention strategies.)

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Neuroma prevention and treatment are primarily dependent on the surgeon. Still, many healthcare professionals must know how to manage, refer patients appropriately, and function as an interprofessional team during the patient journey. Surgical teams must be vigilant about intraoperative nerve damage and adequate repair, as nonrepaired injuries have a high risk of neuroma formation.

If a patient sustains an injury in the community and attends a minor injuries unit or an emergency department, triaging and treating staff should not overlook checking for sensation and motor function. Referring to an appropriate specialist team is essential if nerve damage is suspected. While surgery is the primary form of treatment, patients can try various conservative pain-relieving pharmacological and nonpharmacological options. If they work, the patient does not have to have surgery. For pharmacological options, a pharmacist should participate in optimizing pain control and helping prevent opioid dependence. Nursing staff will prove invaluable in all management phases, whether surgical or conservative and can serve as gatekeepers to the clinician for patient concerns and their monitoring duties. Using this interprofessional approach will drive optimal patient outcomes.