Continuing Education Activity

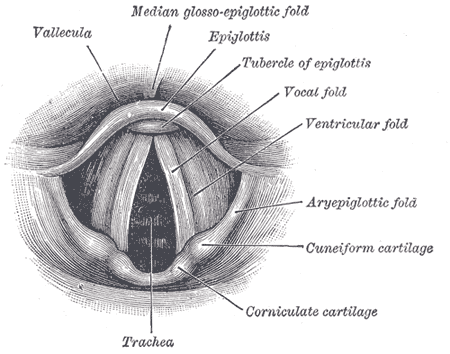

Laryngeal cancers represent one-third of head and neck cancers and may be a significant source of morbidity and mortality. They are most often diagnosed in patients with a significant smoking history. They can involve different sites of the larynx, and the site involved influences the presentation, patterns of spread, and treatment options. Early-stage disease is usually highly curable with either surgical or radiation monotherapy, often larynx-preserving. The late-stage disease is associated with worse outcomes, warrants multimodal therapy, and is less likely to allow for the preservation of the larynx. This activity will review the risk factors for developing laryngeal cancers, treatment approaches, and the role of the interprofessional team in recognizing and treating affected patients (see Image. Anatomy of the Larynx).

Objectives:

Determine the factors associated with increased risk of developing laryngeal cancer.

Identify the typical presenting features of laryngeal cancers.

Identify considerations that influence the management of laryngeal cancers.

Communicate a structured interprofessional team approach to provide effective care and appropriate surveillance of patients with laryngeal cancers.

Introduction

Laryngeal cancers represent one-third of all head and neck cancers and may be a significant source of morbidity and mortality. They are most often diagnosed in patients with significant smoking history, who are also at risk for cancers in the remainder of the aerodigestive tract. They can involve different subsites of the larynx, with different implications in symptomatic presentation, patterns of spread, and treatment paradigms. Early-stage disease is highly curable with either surgical or radiation monotherapy, often larynx-preserving. In contrast, late-stage disease has a worse outcome, warrants multimodal therapy, and is less often larynx-preserving. Speech rehabilitation methods have improved in the modern era for patients requiring laryngectomy.[1]

Each year, about 13,000 laryngeal cancers are diagnosed in the USA, the majority of which are squamous cell cancers. While in the past, the treatment of laryngeal cancer was purely surgical, today, the treatment approach is more towards organ preservation with chemoradiation. Many studies show that this approach produces similar results to total laryngectomy. In addition, today, there are also endoscopic methods of managing laryngeal cancer.

Etiology

Smoking is the most significant risk factor for cancers of the larynx, associated with an estimated 70% to 95% of all cases. Any history of smoking portends higher risk, with current smokers exhibiting increased relative risk versus ex-smokers overall and increased relative risk for supraglottic versus glottic cancers. An association with heavy alcohol consumption has also been characterized, though the independent effect of alcohol is not clear given that combined use with tobacco is noted in most cases. Marijuana smoking may play a role in younger patients. In contrast to other cancers of the head and neck, the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) as a causative agent has not been established.[2]

Other risk factors for laryngeal cancer include the following:

- Advanced age

- A diet low in green leafy vegetables

- Infection with HPV

- A diet rich in fats and salt-preserved meat

- Exposure to paint, asbestos, gasoline fumes, and radiation

Epidemiology

Laryngeal cancer comprised 13,150 new cases in 2017, representing roughly one-third of all head and neck cancers, with 3,710 associated deaths. The mean age of patients is 65 years, with a higher proportion of males versus females and blacks versus whites. In recent years, age-adjusted incidence rates have decreased by about 2% annually, attributed to decreased rates of tobacco smoking. Approximately 98% of laryngeal cancers arise in either the supraglottic or glottic regions, with glottic cancers being 3 times more common than supraglottic cancers and subglottic cancers, representing approximately 2% of all cases. Early-stage cancers are highly curable, with local control rates ranging from 90% to 95% for T1 glottic cancers and 80% to 90% for early-stage supraglottic cancers. Furthermore, such early-stage cancers are generally amenable to vocal cord-sparing surgical therapy. In contrast, locally advanced cancers demonstrate control rates ranging from 40% to 70%, with bulky and/or T4 disease often requiring laryngectomy. However, advances over the years have allowed increased laryngeal preservation and improved speech rehabilitation in patients receiving laryngectomy (see Image. Laryngeal Cancer).

Pathophysiology

The vast majority of laryngeal cancers are well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. A minority of cases represent squamous cell variants, including verrucous, sarcomatoid, and neuroendocrine carcinoma. Verrucous and sarcomatoid carcinomas historically were regarded as radioresistant, though recent experience contradicts this notion. Patterns of spread depend on the location of the primary mass and the inherent lymphatic supply at that location. Laryngeal cancers are divided into supraglottic, glottic, and subglottic subsites, with pathophysiology and treatment differing according to the subsite. Supraglottic

The supraglottis is subdivided into suprahyoid epiglottis, infrahyoid epiglottis, false vocal cords, aryepiglottic folds, and arytenoids. Suprahyoid epiglottic tumors may grow exophytically and superiorly, sometimes larger, before inducing symptoms. In other cases, they may invade inferiorly into the tip of the epiglottis and destroy associated cartilage. Infrahyoid epiglottic tumors, on the other hand, tend to grow circumferentially, where they can involve the aryepiglottic folds; they can then further infiltrate inferiorly into the false vocal cords. They also invade anteriorly into the pre-epiglottic fat space and, subsequently, the vallecula and base of the tongue.

Lymphatic involvement is a pathologic hallmark of supraglottic cancers, in contrast to both glottic and subglottic cancers, with 55% of patients having clinical evidence of nodal metastasis at presentation and 16% with contralateral involvement. To decrease the risk of involvement, cancer principally spreads to levels II, II, and IV of the cervical nodal chain. Locally advanced tumors present a higher risk of nodal metastasis, either by bilateral tumor involvement that likewise increases the risk of lymphatic spread in the bilateral neck and/or by superior extension and invasion into the base of the tongue, vallecula, and pyriform sinus. Glottic

The apex of the ventricle represents the transition from supraglottic to the glottic larynx. The vocal cords range from 3 to 5 mm thick and terminate posteriorly at a commissure with the vocal process. They have a sparse lymphatic supply and thus do not present a risk of lymphatic involvement unless there is a supraglottic or glottic extension. Glottic cancers typically present confined to the anterior portion of the upper free margin of 1 vocal cord. They can induce vocal cord fixation by pure bulk, the involvement of intrinsic muscles and ligaments, or, more rarely, the involvement of the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Subglottic

The subglottis extends superiorly from a point 5 mm below the free margin of the vocal cord and inferiorly to the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage (or 10 mm below the apex of the ventricle). They also have sparse lymphatic supply, with drainage collecting into levels IV and VI of the cervical nodal chain.[3][4]

Histopathology

The vast majority of laryngeal cancers are squamous cell cancers. However, rarely other malignancies may include adenocarcinomas, sarcomas, lymphoma, and neuroendocrine tumors. The spectrum of histopathology of squamous cell carcinoma varies significantly from hyperplasia and dysplasia carcinoma in situ to an invasive cancer.

History and Physical

Patients are typically male with a history of current or past tobacco smoking. Hoarseness is often an early presenting symptom of glottic cancers due to vocal cord immobility or fixation, with pain with swallowing and referred ear pain indicating advanced disease. In contrast, pain with swallowing is the most common early symptom of supraglottic cancer, with hoarseness indicating advanced disease extending into the glottis. Nodal metastases present as fixed, firm, painless masses in the neck. Late symptoms across all subsites include weight loss, dysphagia, aspiration and its sequelae, and airway compromise. The most crucial physical examination component is an invasive assessment of the primary lesion, including indirect laryngoscopy, mirror exam, and often fiberoptic endoscopy. The objective is to assess the local extent of the tumor, noting the size and involvement of adjacent structures and assessing the vocal cord's mobility. Direct laryngoscopy offers an enhanced ability to delineate the extent of disease as well as the ability to obtain tissue specimens. A thorough neck examination is imperative, not only to assess for nodal metastasis but also for the extension of the primary lesion. Tenderness of the thyroid cartilage indicates direct tumor extension and firm fullness palpated just superior to the thyroid notch classically indicates pre-epiglottic space invasion.

Evaluation

In addition to history, physical examination, and direct visualization of the larynx with tissue sampling, as described above, other studies are necessary. Multiple methods of obtaining tissue are feasible. The most valuable are biopsy during direct laryngoscopy of the suspected primary lesion and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of any suspected nodal disease.For all laryngeal cancers, whether suspected to be early or late stage, imaging of the primary lesion and draining lymph nodes is indicated, usually with contrast-enhanced CT of the neck. This study visualizes the neck lymphatics, as well as structures that cannot be assessed adequately even with direct laryngoscopy, such as the subglottic region, as well as to detect subtle signs of disease extension, such as minor invasion into the thyroid cartilage, all of which are crucial for accurate staging.

The suspected locally advanced disease would prompt contrast-enhanced CT of the chest as well as PET/CT to rule out distant metastases. Suspected invasion into the hypopharynx may prompt esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and/or barium swallow, which may differentiate the correct aerodigestive tissue of cancer origin.

Before any surgery, blood work is necessary, including complete blood count, platelet count, liver and renal function, blood type, thyroid function, electrolytes, and albumin levels.

During the workup of laryngeal cancer, the following factors are considered:

- Vocal cord mobility

- Number of regions involved

- Presence of cervical or distant metastatic lesions

- Involvement of the base of the tongue

- Involvement of the paraglottic and pre-epiglottic space

- Involvement of the thyroid cartilage

- Involvement of the carotid artery and sheath

- Invasion of the esophagus

- Invasion of soft tissue and adjacent laryngeal muscles

- Involvement of neck lymph nodes

Treatment / Management

Early-Stage Laryngeal Cancer

Early-stage laryngeal cancers, inclusive of T1-2N0 disease, are treated successfully with a single, locally-directed treatment modality, whether local radiation therapy or surgery.

T1-2N0 Glottic Cancer

Local radiation therapy or surgery is recommended, with a choice of modality highly dependent on provider experience and patient preference. Given the sparse lymphatic drainage of the true glottis, these modalities all share a common fundamental principle: they only address the primary tumor. Level I data comparing the 2 approaches do not exist, but local control rates from retrospective experience are comparable between surgical approaches and respiratory therapy (RT). Voice-sparing surgery is an option in many, but not all, of these cancers. In 1 experience, total laryngectomy was the required surgical approach in 10% of T1 and 55% of T2 tumors. Other approaches include transoral laser excision, laryngofissure, and partial laryngectomy. Despite no evidence comparing surgery and RT, randomized data demonstrate superior voice preservation with definitive RT versus transoral laser excision.

T1-2N0, Selected T1-2N1/T3N0-1 Supraglottic Cancer

Similar to early-stage glottic cancers, supraglottic cancers can be managed with either larynx-sparing surgical or RT monotherapy, with demonstrated overall comparable efficacy. The major difference between glottic cancers is the management of the neck, given the risk of nodal metastases. Surgical approaches include endoscopic resection or partial supraglottic laryngectomy for T1-2 and low-volume T3 disease, with neck dissection often indicating T2 or T3 lesions. Adjuvant RT is given to many patients, with common indications including positive nodal disease, extracapsular extension, and positive margins. Definitive RT often includes at-risk cervical nodal stations, generally levels II to IV.

Locally Advanced Laryngeal Cancers

Locally advanced cancers, inclusive of T3-4N1-3 disease, are more difficult to treat and typically involve combination therapy. These cancers, if surgically resectable, are not amenable to laryngeal preservation surgery, while definitive radiation concurrent with cisplatin chemotherapy remains an option for laryngeal preservation. In contrast to early-stage disease, the therapeutic approach to locally advanced disease is based on level I evidence, with combined chemotherapy and radiation demonstrating improved locoregional control and larynx preservation. In T4 disease, laryngectomy and adjuvant RT have demonstrated similar locoregional control rates compared to chemoradiation and salvage surgery. Larynx-preserving chemoradiation is not recommended for T4 disease and is associated with inferior survival.[5][6][7][8]

Post-operative RT is indicated in the case of emergent tracheostomy due to morbid tumor invasion (to reduce risk of tumor spread into the tracheostomy), advanced tumor and nodal stage on surgical pathology (pT3-4, pN2-3), as well as other high-risk pathologic features, including close margins (less than 5 mm), perineural invasion, lymphovascular space invasion, and extracapsular extension. Moreover, close or involved margins, multiple positive nodes, and extracapsular extension necessitate the addition of chemotherapy concurrent with RT.[9][10][11][12][13]

The reader needs to appreciate that the novel methods of treating laryngeal cancer have not significantly improved the survival rates but instead decreased the morbidity of surgery. Recently transoral laser microsurgery has been popularized for early glottic and supraglottic cancers. However, surgeon experience is critical. The surgery involves piecemeal removal of the cancer and evaluation of the margins.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis to consider and rule out regarding laryngeal cancer include the following:

- Bacterial lymphadenopathy

- Polyps on the vocal cord(s)

Staging

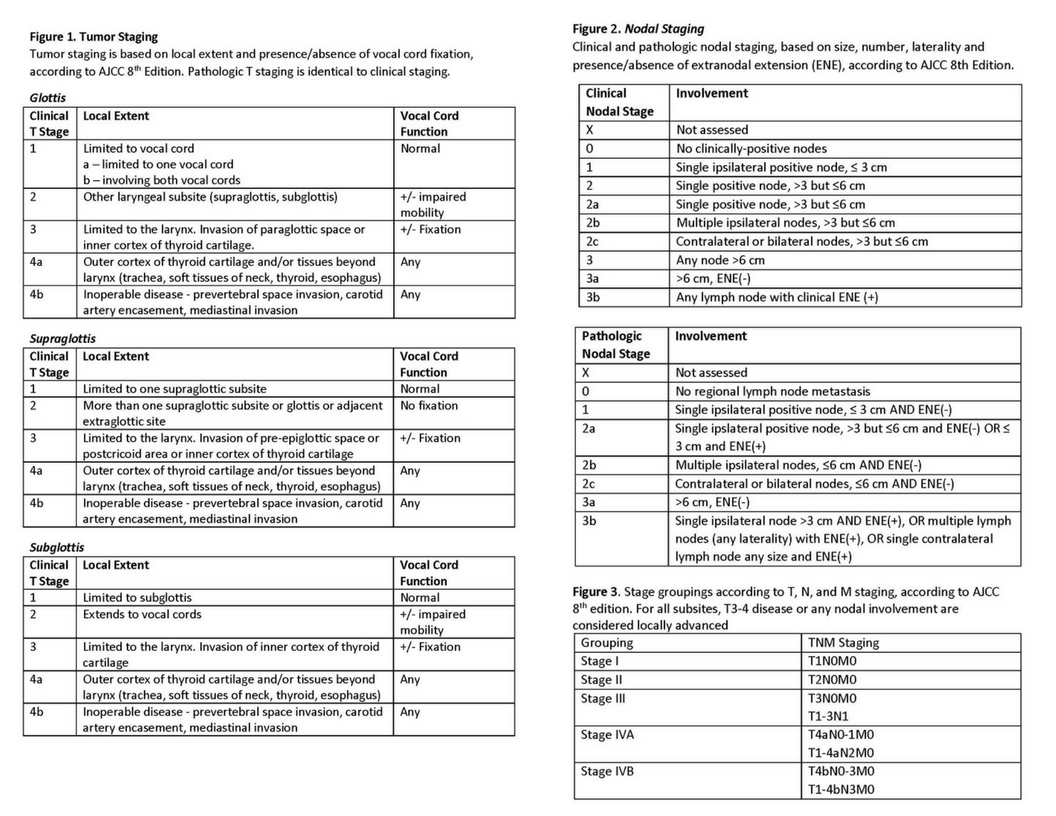

The American Joint Committee on Cancer, 8th Edition Cancer Staging Manual (AJCC) bases primary tumor staging for glottic and supraglottic cancers on the local extent and the presence or absence of vocal cord fixation (see Image. Tumor and Nodal Staging of Laryngeal Cancer).

Table 1: Tumor staging, based on local extent and presence/absence of vocal cord fixation. Pathologic T staging is identical to clinical staging.

Table 2: Clinical and pathologic nodal staging, based on size, number, laterality, and presence/absence of extranodal extension (ENE).

Table 3: Stage groupings according to T, N, and M staging. T3-4 disease or any nodal involvement is considered locally advanced for all subsites.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of laryngeal cancer is with an interprofessional team that includes an ENT surgeon, oncologist, dietitian, pulmonologist, speech therapist, intensivist and radiation therapist. The majority of patients first present with hoarseness, otalgia, dysphagia, and weight loss to the primary care provider. Patients are typically male with a history of current or past tobacco smoking. A referral to an ENT surgeon should be made if the hoarseness is prolonged and associated with other features indicating a malignancy.

Due to the complexity of treatment, an interprofessional approach involving an ENT or oncologic surgeon, oncologist, speech therapist, respiratory therapist, and other clinicians is warranted for evaluation and follow-up therapy. The patient and family require coordinated education regarding procedures and follow-up care to obtain the best outcomes.The most crucial physical examination component is an invasive assessment of the primary lesion, including indirect laryngoscopy, mirror exam, and often fiberoptic endoscopy. The treatment of laryngeal cancer is surgery which is technically demanding and complex. Postoperative complications are common, and patients need close monitoring for airway patency. The outcomes for early-stage laryngeal cancer are good, but those with advanced cancer have a grim prognosis.[14][15]