Continuing Education Activity

Ulnar collateral ligament injury of the thumb, also known as skier's thumb or gamekeeper's thumb, is an injury of the ulnar collateral ligament of the first metacarpophalangeal joint. Injuries are often sustained by activities or traumatic events that force the thumb into extreme abduction or hyperextension. Men account for 60% of known injuries, often due to falls and injuries during sports activities such as skiing, baseball, and football. Proper management, including imaging with ultrasound or MRI, conservative treatment, or surgery, has a high success rate. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the thumb. The role of interprofessional team members when collaborating to provide well-coordinated care and enhance outcomes for affected patients is highlighted.

Objectives:

Differentiate the mechanisms of injury that commonly lead to ulnar collateral ligament injuries.

Identify the differential diagnoses of ulnar collateral ligament injuries.

Implement the strategies for the management of ulnar collateral ligament injuries.

Collaborate with other healthcare professionals to manage care for patients affected by ulnar collateral ligament injury.

Introduction

Clarification: This article refers to ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the first metacarpophalangeal joint of the hand (Gamekeeper's thumb) and not injuries to the ulnar collateral ligament of the elbow that often lead to Tommy John surgery.

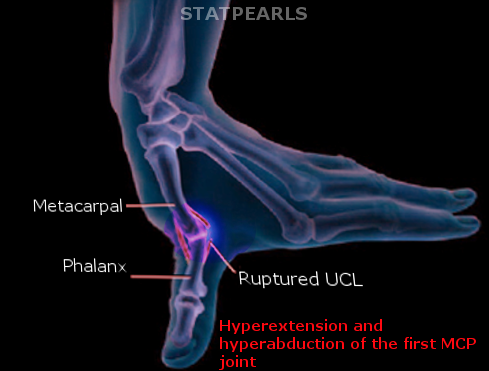

Ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the thumb were first described in gamekeepers who sustained the injury from the repetitive nature of breaking the neck of small game such as birds and rabbits. Hence, this was originally referred to as the gamekeeper's thumb.[1] The recurrent thumb hyperextension sustained by gamekeepers would mechanically lead to degeneration and tears of the ulnar collateral ligament at the base of the first metacarpophalangeal joint. More recently, this condition has also been referred to as skier's thumb since it is more commonly observed in individuals who fall while holding ski poles, which mechanistically causes the same type of hyperextension thumb injury.[2]

Etiology

The ulnar collateral ligament is located at the base of the thumb at the first metacarpophalangeal joint. The role of the ulnar collateral ligament is to assist in the stability of the thumb near its base as it meets the first metacarpal. Any mechanism, such as a fall or strike injury that forces the thumb to become forcefully abducted, can threaten the integrity of the ulnar collateral ligament. When a valgus force is placed on the thumb while in abduction or extension, there is a risk of hyperabduction or hyperextension injury to the ulnar collateral ligament.[3] This injury is more frequently observed in skiers since individuals can fall and strike their thumb on a fixed ski pole.[2] Repetitive abduction at the thumb, as was required in gamekeepers' tasks, may cause a chronic ulnar collateral injury pattern.[4][5]

Epidemiology

Ulnar collateral ligament injuries are observed more frequently in the male population, with a 60% predominance in this gender.[6] Specific patient populations that may be at risk include certain sporting activities, including, but not limited to, skiing, baseball, and javelin. Furthermore, simple mechanisms such as falls in disabled or older adults may result in this injury pattern.

Pathophysiology

The anatomic function of the thumb is complex and beyond the scope of this article; however, it is essential to recognize that the ulnar collateral ligament assists in stabilizing the thumb at the metacarpophalangeal joint. To adequately grasp and hold onto objects, the thumb coordinates with hand muscles, finger muscles, and ligamentous structures, including the ulnar collateral ligament. By understanding this mechanism of thumb function, one can see how forceful hyperextension (or extreme abduction) may tear the ulnar collateral ligament. Tears can be classified as partial, complete, or chronic. As observed in other acute joint injuries, the patient may have swelling and tenderness at the first metacarpophalangeal joint. There may also be instability or laxity noted at that joint.[7]

History and Physical

Typically, the patient with ulnar collateral ligament injury complains of discomfort localized to the first metacarpophalangeal joint area. There may be accompanying swelling near or at the thumb base. There is usually a history of falls or trauma, causing extreme thumb abduction or hyperextension. The patient may present acutely in the immediate post-injury timeframe or may not present for quite some time if the injury is more chronic. In both situations, pain and occasionally weakness may be present, especially when attempting to hold onto objects, in particular with a pincer grasp.

The physical examination can be especially helpful in discerning this diagnosis. A valgus stress test by abducting the thumb at its base can help to determine any laxity or complete disruption of the ulnar collateral ligament. Comparison with the unaffected thumb can help to establish a baseline to delineate the degree of tear or injury. In situations where partial tears exist, there will be increased laxity or mobility on valgus stress testing. A lack of endpoint during such testing would indicate a complete tear with total instability at the thumb base. One method to help isolate the ulnar collateral ligament during testing is asking the patient to flex the first metacarpophalangeal to 45 degrees. This helps to test the ulnar collateral ligament more precisely than other ligaments at the thumb base.

Based on orthopedic studies, the typical degree of laxity, which should raise suspicion for ulnar collateral ligament injury, is any amount greater than 15 to 20 degrees on abduction or valgus stress testing. This should be compared to the unaffected thumb. Furthermore, if the degree of laxity is more than 30 degrees, this is very suggestive of ulnar collateral ligament tear. While this is described in the orthopedic literature, the provider may have difficulty accurately measuring the degree of ulnar collateral ligament laxity in the actual clinical environment.[8]

Evaluation

Imaging in the setting of an acute ulnar collateral ligament injury is typically not helpful. However, plain films of the thumb may help rule out fracture or bony abnormalities, particularly of the thumb base (proximal phalanx). The ulnar collateral ligament inserts along the medial (ulnar) aspect of the proximal phalanx of the thumb. Hence, an avulsion fracture may be present in the ulnar collateral ligament injury setting. In most cases, however, plain x-ray imaging is unrevealing, even normal, in these patients.

Ultrasound can be used at the bedside in real-time to assess laxity at the first metacarpophalangeal joint. The use of the hockey stick probe by an experienced technician allows for a detailed examination of small structures such as the ulnar collateral ligament.[9] As with the physical exam, ultrasound imaging can be done on both thumbs to compare one side to another and to establish a baseline on the unaffected side.

Magnetic resonance imaging may be challenging to obtain acutely. Still, this technique has the highest sensitivity and specificity (nearly 100%) for diagnosing ulnar collateral ligament injury, including tears or ruptures.[10]

Treatment / Management

As with most musculoskeletal injuries, ulnar collateral ligament injuries can be treated acutely with R-I-C-E therapy: rest, ice, compression, and elevation. Immobilization is also helpful through the application of a thumb spica splint.[11]

If the patient has a bony injury, such as an avulsion fracture in the setting of ulnar collateral ligament injury, they should be referred urgently to an orthopedic or hand specialist. Similarly, if the physical examination shows significant laxity (greater than 15 to 20 degrees compared to the unaffected thumb or greater than 30 degrees outright), then urgent referral to a hand surgeon is indicated.

Splinting immobilization may suffice for treating partial tears, but evaluation by a hand surgeon is still prudent. The typical immobilization timeframe recommended is three weeks. Subsequently, these nonsurgically treated injuries can undergo physical therapy and rehabilitation. Therapy includes both passive and active measures, along with strengthening exercises. Immobilization is recommended for an additional three weeks when the patient is not actively undergoing physical therapy, yielding approximately six weeks of immobilization therapy. Following this timeframe, surgical referral should be pursued for patients with persistent weakness or pain.

In most reported studies, those patients who sustain complete ulnar collateral ligament tears and undergo surgery do well without significant complications. One study of sports-related injuries suggested an aggregate 98.1% successful return to play after surgery with no significant decreased performance and a 10.3% postoperative complication rate.[12] Generally, early surgical intervention is required for complete tears to prevent the development of the complication known as the Stener lesion. This complication occurs when the disrupted end of the ulnar collateral ligament migrates superficially and lies on top of the adductor pollicis aponeurosis and muscle. Given this altered anatomy, the ligament cannot heal appropriately, and surgery is recommended as the definitive treatment.[13]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for ulnar collateral ligament injuries includes other musculoskeletal injuries that may be sustained to the hand and thumb. This includes tendinous injury such as adductor pollicis disruption. This may also include any dislocation of the thumb at the metacarpophalangeal joint. Bony injuries such as Rolando or Bennett fractures should also be considered. Arthritis of the thumb joint may also be considered in the differential.

Prognosis

Partial tears of the ulnar collateral ligament are usually treated with splinting alone and, despite the long duration of immobilization, tend to heal well. In a minority of patients, there may be persistent stiffness and pain. As discussed in the treatment and management above, surgery typically can be performed without significant complications in the setting of complete ulnar collateral ligament tears. In those individuals who develop Stener lesions or go without treatment, chronic changes can be observed in the metacarpophalangeal joint space. Generally, the patient should wait at least 6 weeks before returning to work or sports.[14]

Complications

Conservative treatment using rest, ice, elevation, pain management with over-the-counter anti-inflammatory and analgesic drugs, and splinting are generally sufficient for treating partial tears and strains. Returning to activity too soon and without appropriate rehabilitation may result in loss of function. Surgery has inherent risks related to anesthesia, post-surgical infection risk, and potential nerve injury. Failure to surgically repair more severe injuries may also result in loss of function.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education should focus on pain management, conservative treatment with ice, and continued stabilization with a splint until released by the physician to rehabilitate the injured hand(s). If surgery is part of the treatment plan, postoperative home management plans should be delineated for the patient. There is no formal need for deterrence other than educating about future falls and injury risks.

Pearls and Other Issues

When the thumb is placed in extreme abduction or hyperextension, there is a risk of injury to the ulnar collateral ligament, stabilizing the base of the thumb at the first metacarpophalangeal joint. This injury is more frequently observed in one specific group, skiers since individuals can fall and strike their thumb on a fixed ski pole. Hence, it is the synonymous term of skiers' thumb.

Laxity at the first metacarpophalangeal joint (thumb base) on abduction stress testing suggests ulnar collateral ligament injury. Providers should compare to the contralateral unaffected thumb for a baseline reference point.

As with most other musculoskeletal injuries, fractures should be ruled out with standard plain films, but imaging modalities are typically of limited utility in this injury.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Although most cases of ulnar collateral ligament injury do not require surgery, referral to an orthopedic or hand surgery specialist is prudent for long-term planning and therapy referral. In the acute setting, such as the emergency department, the provider's goals for therapy should include acute pain relief and immobilization with a thumb spica splint. Providers, nurses, or techs can perform splint placement. The (orthopedic) nursing staff can provide splint care and patient education. Further therapy that the patient can perform at home includes ice therapy, rest, and elevation. Complete ulnar collateral ligament tears usually mandate surgical intervention.

Complications of an untreated complete tear include the Stener lesion and the development of chronic arthritis. Judicious use of pain medication can be considered. Collaborating with specialists and working in the acute setting with an interprofessional team approach will help ensure the best outcome for these patients.