Continuing Education Activity

Piriformis syndrome occurs due to sciatic nerve entrapment at the level of the ischial tuberosity. While there are multiple factors that may contribute to piriformis syndrome, the clinical presentation is fairly consistent. Patients often report pain in the gluteal region that is characterized as shooting, burning, or aching down the back of the leg. In addition, numbness in the buttocks and tingling sensations along the distribution of the sciatic nerve is not uncommon.

Objectives:

- Outline the differential diagnosis of gluteal pain that radiates down the back of the leg.

- Review the evaluation of piriformis syndrome.

- Describe how to manage a patient with piriformis syndrome.

- Summarize how an optimally functioning interprofessional team would coordinate care to enhance outcomes for patients with piriformis syndrome.

Introduction

Piriformis syndrome is a clinical condition of sciatic nerve entrapment at the level of the ischial tuberosity. While there are multiple factors potentially contributing to piriformis syndrome, the clinical presentation is fairly consistent, with patients often reporting pain in the gluteal/buttock region that may "shoot," burn or ache down the back of the leg (i.e. "sciatic"-like pain). In addition, numbness in the buttocks and tingling sensations along the distribution of the sciatic nerve is not uncommon.

The sciatic nerve runs just adjacent to the piriformis muscle, which functions as an external rotator of the hip. Hence, whenever the piriformis muscle is irritated or inflamed, it also affects the sciatic nerve, which then results in sciatica-like pain. The diagnosis of piriformis syndrome is not easy and is based on clinical history and presentation. Other conditions that can also mimic the symptoms of piriformis syndrome include lumbar canal stenosis, disc inflammation, or pelvic causes.[1][2]

Etiology

Sciatic nerve entrapment occurs anterior to the piriformis muscle or posterior to the gemelli-obturator internus complex at the level of the ischial tuberosity. The piriformis can be stressed due to poor body mechanics in a chronic condition or an acute injury with the forceful internal rotation of the hip. There are also anatomic anomalies that may contribute to compression, including a bipartite piriformis, direct invasion by a tumor, anatomical variations of the course of the sciatic nerve course, direct tumor invasion, or an inferior gluteal artery aneurysm that may compress the nerve.

Causes of piriformis syndrome include the following:[2]

- Trauma to the hip or buttock area

- Piriformis muscle hypertrophy (often seen in athletes during periods of increased weightlifting requirements or pre-season conditioning)

- Sitting for prolonged periods (taxi drivers, office workers, bicycle riders)

- Anatomic anomalies:

- Bipartite piriformis muscle

- Sciatic nerve course/branching variations with respect to the piriformis muscle

- In >80% of the population, the sciatic nerve courses deep to and exits inferiorly to the piriformis muscle belly/tendon[3]

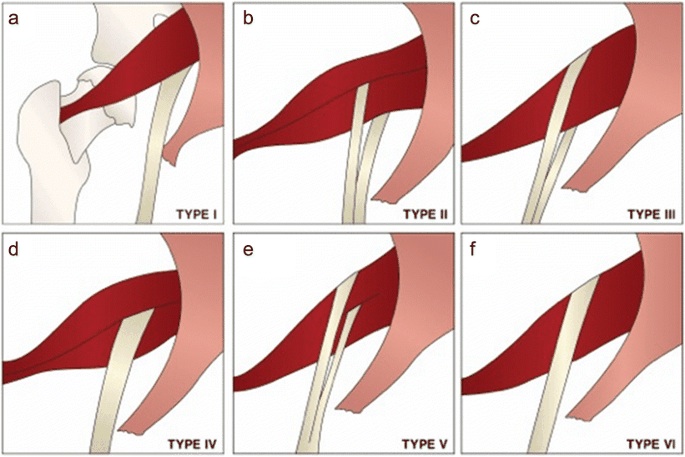

- Early (proximal) divisions of the sciatic nerve into its tibial and common peroneal components can predispose patients to piriformis syndrome, with these branches passing through and below the piriformis muscle or above and below the muscle[4]

Epidemiology

Piriformis syndrome may be responsible for 0.3% to 6% of all cases of low back pain and/or sciatica. With an estimated amount of new cases of low back pain and sciatica at 40 million annually, the incidence of piriformis syndrome would be roughly 2.4 million per year. In the majority of cases, piriformis syndrome occurs in middle-aged patients with a reported ratio of male to female patients being affected 1:6.[2]

Pathophysiology

The piriformis muscle is flat, oblique, and pyramidal-shaped. It originates anterior to the vertebrae (S2 to S4), the superior margin of the greater sciatic foramen, and the sacrotuberous ligament. The muscle then crosses through the greater sciatic notch and then hooks on the greater trochanter of the hip bone. When there is an extension of the hip, the muscle acts primarily as an external rotator, but when the hip is in flexion, the piriformis muscle acts like a hip adductor. The piriformis muscle receives innervation from nerve branches coming off L5, S1, and S2. When the piriformis muscle is overused, irritated, or inflamed, it leads to irritation of the adjacent sciatic nerve, which runs very close to the center of the muscle.

Sciatic nerve entrapment occurs anterior to the piriformis muscle or posterior to the gemelli-obturator internus complex, which is in line with the anatomical location of the ischial tuberosity. Piriformis can be stressed due to poor body posture chronically or some acute injury that results in a sudden and strong internal rotation of the hip.[5]

History and Physical

Patients with piriformis syndrome may present with the following:

- Chronic pain in the buttock and hip area

- Pain when getting out of bed

- Inability to sit for a prolonged time

- Pain in the buttocks that is worsened by hip movements

Patients will often present with symptoms of sciatica, and it can often be difficult to differentiate the origin of the radicular pain secondary to spinal stenosis versus the piriformis syndrome. The pain may radiate into the back of the thigh, but at times it may also occur in the lower leg at dermatomes L5 or S1.[6]

The patient may also complain of buttock pain, and typically the palpation may reveal mild to moderate tenderness around the sciatic notch. By performing FAIR (flexion, adduction, and internal rotation), the health care provider may be able to reproduce the patient's symptoms.

The FAIR test is done by examining the patient in the supine position. Then one should ask the patient to flex the hip and move it along the midline. At the same time, the investigator should rotate the lower leg- this maneuver will apply tension to the piriformis muscle. At the same time, palpation will reveal tenderness over the muscle belly that stretches from the sacrum to the greater trochanter of the femur.

Evaluation

The diagnosis is primarily clinical and is one of exclusion. On physical examination, the practitioner should try to perform stretching maneuvers to irritate the piriformis muscle. Furthermore, manual pressure around the sciatic nerve may help reproduce the symptoms.

These stretches include:

- Freiberg (forceful internal rotation of the extended thigh)

- Pace (resisted abduction and external rotation of the thigh)

- Beatty (deep buttock pain produced by the side-lying patient holding a flexed knee several inches off the table)

- FAIR (flexion, adduction, internal rotation) maneuvers

Some of the disorders that also need to be ruled out include facet arthropathy, herniated nucleus pulposus, lumbar muscle strain, and spinal stenosis.

Diagnostic modalities such as ultrasound, MRI, CT, and EMG are mostly useful in excluding other conditions, as above. The electrophysiologic approach has been used to diagnose piriformis syndrome by noting the presence of H waves. However, magnetic resonance neurography may show the presence of irritation of the sciatic nerve just adjacent to the sciatic notch. At this location, the sciatic nerve crosses just inferior to the piriformis muscle. Magnetic resonance neurography is not readily available in all clinics and is considered an experimental study. Private insurance may not reimburse the costs of the study.[7]

Treatment / Management

Treatment includes short-term rest (not more than 48 hours), use of muscle relaxants, NSAIDs, and physical therapy (which entails stretching the piriformis muscle, range of motion exercises, and deep-tissue massages). In some patients, injection of steroids around the piriformis muscle may help decrease the inflammation and pain.[8]

Anecdotal reports suggest that botulinum toxin may help relieve symptoms. However, the duration of pain relief is short-lived, and repeat injections are required.[9]

Surgery is the last consideration in patients with piriformis syndrome. It should only be considered in patients who have failed conservative therapy, including physical exercise. The surgery may help decompress the nerve if there is any impingement, or the surgeon may lyse any adhesions or remove scars from the nerve. However, the results after surgery are not always predictable, and some patients continue to have pain.[10]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes:[11]

- Hamstring injury

- Lumbosacral disc injuries

- Lumbosacral discogenic pain syndrome

- Lumbosacral facet syndrome

- Lumbosacral radiculopathy

- Lumbosacral spine sprain

- Lumbosacral spondylolisthesis

- Lumbosacral spondylolysis

- Sacroiliac joint injury/dysfunction

- Inferior gluteal artery aneurysm or pseudoaneurysm

- Malignancy/tumors

- Arteriovenous malformations

Prognosis

A number of patients with piriformis syndrome will show symptomatic improvement after local trigger-point injection. If this is combined with rehabilitation exercises, then recurrences are rare.

Individuals who undergo surgery for the release of adhesions and scars may take a few months to return to full activity.

Complications

Complications related to surgery include:

- Nerve injury

- Sciatic nerve injury is the most common

- Infection

- Bleeding

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Once the diagnosis of piriformis syndrome is made, the patient should be encouraged to enter a physical therapy program. Evidence shows that both manual and stretching therapies are beneficial.

Consultations

- Orthopedic surgeon

- Physical therapist

- Neurologist

- Osteopathic clinician

Pearls and Other Issues

Athletes with piriformis syndrome may return to activities when they can demonstrate the pain-free range of motion, increased strength of the affected side, and performance without any discomfort. Patients must stretch and warm-up before the activity. The time to return to exercise or sporting events depends on the severity of symptoms and the type of treatment undertaken. In general, the longer one does not seek medical care or physical therapy, the longer is the course of rehabilitation.[12]

Patients with piriformis syndrome should adhere to the following:

- Avoid prolonged sitting

- Stretch exercises 2 to 3 times a day and before participating in sports

- The patient should be educated on a continual basis. Patients should be told about the importance of maintaining compliance if they want a positive outcome.

- In most cases, recurrent pain can be prevented by performing stretching exercises for at least 5 to 10 minutes prior to full participation and avoiding risk factors like prolonged seating.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

As society advances and work conditions become more efficient, more people today sit for prolonged hours than ever before. And prolonged sitting comes with repercussions like the piriformis syndrome. The syndrome can be disabling with moderate-to-severe buttock or low back pain. However, the good thing is that the syndrome can be prevented in the majority of people. The key thing is to educate the public on how to prevent the syndrome. It is here that the rehabilitation consultant, sports nurse, physiotherapist, and outpatient nurse can play an important role. Once the diagnosis and treatment of piriformis syndrome are completed, the patient needs to be educated on the importance of eliminating the risk factors like obesity, sedentary lifestyle, smoking, and lack of exercise. In hospitals, nurses should ensure that patients are out of bed in a chair and ambulating. Those with recent surgery may benefit from a physical therapy consult. Prior to any physical activity, 5-10 minutes should be spent on stretching the muscles, ligaments, and tendons- as this can lessen the risk of injury. If the occupation requires prolonged sitting, one should take 'sitting breaks' every hour and walk around for a few minutes. Regular taking part in exercise is the key. Even walking can help prevent piriformis syndrome. Finally, the patient should be told of the importance of exercise compliance. [13][14](Level V)

Outcomes

Piriformis syndrome, when not treated, can be disabling and leads to poor quality of life. However, when treated, the prognosis for most patients is excellent. Most people become symptom-free within 1-3 weeks after starting an exercise program, but unfortunately, relapse of symptoms is very common when compliance with exercise is low. The key is to avoid prolonged sitting. The role of surgery to manage piriformis syndrome remains debatable and is almost never the first-choice treatment.[15][16][3] (Level V)