Continuing Education Activity

Colloid cysts are benign growths usually located either in the third ventricle or at or near the foramen of Monro, which is found at the anterior aspect of the brain's third ventricle. The cysts comprise epithelial lining filled with gelatinous material that commonly contains mucin, old blood, cholesterol, and ions. Colloid cysts can cause a variety of symptoms, including headaches, diplopia, memory problems, and vertigo. Rarely, colloid cysts have been reported to cause sudden death. This activity reviews the pathophysiology, evaluation, and management of colloid cysts and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the care of patients with these lesions.

Objectives:

Identify the etiology of colloid cysts.

Describe the presentation of colloid cysts.

Outline the treatment and management options available for colloid cysts.

Describe interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance the diagnosis and management of colloid cysts and improve outcomes.

Introduction

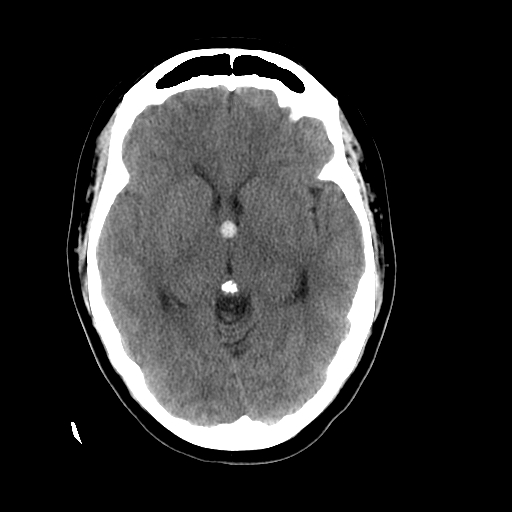

The colloid cyst is a benign growth usually located in the third ventricle and at or near the foramen of Monro, which is at the anterior aspect of the brain's third ventricle.[1] The colloid cyst is an epithelial-lined cyst filled with gelatinous material. The gelatinous material commonly contains mucin, old blood, cholesterol, and ions (See Image. Head CT, Colloid Cyst at the Foramen of Monro).[1]

Colloid cysts can cause various symptoms, including headaches, diplopia, memory issues, and vertigo. Rarely colloid cysts have been cited as a cause of sudden death. When colloid cysts are symptomatic, they most commonly cause headaches, nausea, and vomiting secondary to obstructive hydrocephalus. The obstructive hydrocephalus is precipitated by blocking the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) egress from the lateral ventricles at the foramen of Monro, which connects the lateral and third ventricles.[2]

Etiology

The precise etiology of colloid cysts is unclear and still debatable. In the early 20th century, the suggested etiology was that the cyst was a remnant of the paraphysis element. The paraphysis element is an embryonic structure located at the diencephalon's anterior portion between the telencephalon's 2 hemispheres.

As colloid cysts have also been found in the cerebellum, frontal lobe, and pontomesencephalon, there have been other theorized origins of the colloid cysts. Other etiologies include remnants of respiratory epithelium, an ependymal cyst from the diencephalon, and invagination of the neuroepithelium of the lateral ventricle, causing a cyst to form.[2]

Epidemiology

Colloid cyst accounts for less than 2% of all primary brain tumors. More than 99% of all colloid cysts are reported to occur at the rostral end of the third ventricle, at or near the foramen of Monro. Colloid cysts account for approximately 1 in 5 intraventricular primary brain tumors. Most patients diagnosed with a colloid cyst are in their third through the seventh decade of life, but cases have rarely been reported as early as the first year of life.

Pathophysiology

Most colloid cysts identified are currently asymptomatic and identified incidentally on imaging. When a colloid cyst does cause issues, it most commonly causes obstructive hydrocephalus.

The colloid cyst is most commonly found in the rostral third ventricle at or near the foramen of Monro. The foramen of Monro is the conduit of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) outflow from the lateral ventricles to the third ventricle. A colloid cyst can act as a ball valve, stopping CSF flow from the lateral ventricles. If this occurs, CSF backs up into the lateral ventricles and causes ventriculomegaly and hydrocephalus. Some have posited that colloid cysts can cause intermittent obstructive hydrocephalus, thus causing intermittent symptoms.

Colloid cysts tend to grow very slowly over time. Some may never reach a size that will cause an issue and can be followed, whereas others grow more quickly and become symptomatic with time.

Histopathology

Grossly, a colloid cyst is a unilocular round structure filled with a viscous material. Microscopically, the cell wall is unicellular and typically composed of columnar epithelium, which may or may not be ciliated. The cyst contents are typically void of living cells and composed of desquamated ghost cells and filamentous material. The mucin stains are positive for periodic acid-Schiff (PAS). The epithelial cyst wall-stains are positive for keratin and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA).

History and Physical

Most colloid cysts are found incidentally on brain imaging for other reasons. When a colloid cyst is symptomatic, it most commonly causes noncommunicating hydrocephalus. Symptoms of hydrocephalus can include headaches, nausea, vomiting, lethargy, coma, and death. If the hydrocephalus is slowly progressive, the patient can have more subtle findings, including urinary incontinence, trouble with walking, falls, altered mentation, and memory deficits.

The physical exam should be normal for asymptomatic colloid cysts. However, if the patient has hydrocephalus from the colloid cyst, physical exam findings may include lethargy, failure of upward gaze, unsteady gait, ataxia, increased reflexes, and papilledema or frontal release signs if the hydrocephalus is chronic.

Evaluation

Immediate evaluation of suspected colloid cysts includes the airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs) of emergency medical management if the patient may be at risk for acute hydrocephalus and neurologic deterioration. A thorough neurologic exam is important to identify any neurologic deficits, but imaging remains the cornerstone of evaluation for patients with a colloid cyst. Plain radiographs of the head typically do not visualize a colloid cyst, so computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head are more important imaging studies.

CT Head

CT of the head can be quickly obtained to identify acute hydrocephalus. On CT imaging, the colloid cyst is typically a circular, hyperdense mass at or near the foramen of Monro. Rarely are colloid cysts isodense, hypodense, or calcified.

MRI Brain

MRI is the preferred method for imaging colloid cysts. On T1 sequencing, a colloid cyst can have variable characteristics and be either hyperintense, isointense, or hypointense. With gadolinium administration, the colloid cysts should not be enhanced. Rarely a peripheral enhancement will be noted around the colloid cyst, which most likely represents a vessel stretched over the colloid cyst.

On T2 sequence imaging, most colloid cysts are hypointense. They may also have a heterogeneous T2 signal. Low signal intensity on T2 imaging may suggest the contents of the colloid cyst are more viscous and, thus, harder to aspirate. On fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequencing, most colloid cysts have a similar intensity to the surrounding CSF. Most colloid cysts have decreased signal intensity on diffusion-weighted imaging.

Treatment / Management

Treatment and management depend if the colloid cyst is found incidentally or is symptomatic.[3][4][5][6] It should be treated if the colloid cyst is symptomatic and causes hydrocephalus. For acute, life-threatening hydrocephalus, treatment should be the next priority after ensuring adequate airway, breathing, and circulation. An external ventricular drain (EVD) can be placed to relieve acute hydrocephalus and may be a life-saving procedure.

After acute, life-threatening hydrocephalus has either been treated or ruled out, the clinician can deal with the colloid cyst. Current treatment options include craniotomy with excision via a transcallosal or transcortical route, endoscopic removal, and stereotactic aspiration.

Craniotomy for Colloid Cyst Removal

A colloid cyst can be removed with a craniotomy. A craniotomy is a surgery where an incision is made in the scalp, and part of the skull is removed for the duration of the surgery; then, the skull is put back in place. Two separate routes exist to remove the colloid cysts: transcallosal and transcortical. In the transcallosal approach, the 2 frontal hemispheres are split apart, and a surgical corridor is created through the rostral end of the genu of the corpus callosum to access the colloid cyst. For the transcortical route, a surgical corridor is developed directly through the brain cortex, most commonly through the right frontal and middle gyrus, to access the lateral ventricle. The colloid cyst can then be removed through the lateral ventricle.

Removing a colloid cyst via a craniotomy has the highest up-front surgical risk but may have the lowest recurrence and reoperation rate. The open craniotomy provides more degrees of freedom for access to the colloid cyst. It may be more suitable for larger colloid cysts but does have limitations based on the approach chosen.[7][8]

Endoscopic Removal of a Colloid Cyst

An endoscopic surgery consists of making a small incision in the scalp and a small hole in the bone. A small tube, typically called a sheath, is advanced through the brain to access the lateral ventricle. An endoscope can then be passed into the lateral ventricle to remove the colloid cyst. In its simplest form, an endoscopic is a tube with a light, camera, and working channel. The light provides illumination for the camera to see what is going on. The working channel allows the surgeon to get instruments and tools before the camera performs surgery.

Endoscopic removal of a colloid cyst tends to have less up-front risk than open surgery but also may have a slightly higher reoperation rate than open surgery. The endoscopic approach may not be suitable for all colloid cysts depending on the size and location of the cyst.[8][9]

Stereotactic Aspiration of a Colloid Cyst

A third option to treat a colloid cyst is a stereotactic aspiration. This is performed by making a small incision in the scalp and then a small hole in the bone. The surgeon then advances a needle through the brain and into the cyst using some variety of either frame-based or frameless neuronavigation. The contents of the colloid cyst may be able to be aspirated, decreasing its size.

Aspiration of a colloid cyst may not be achievable if the contents of the colloid cyst are particularly thick or if there is no safe corridor to the colloid cyst. Stereotactic aspiration of a colloid cyst has less relative surgical risk than an endoscopic or open resection of the colloid cyst. Still, it has the highest reoperation rate compared to the other 2 treatment modalities. With the aspiration of the colloid cyst, the cyst is left in place and decompressed. The cyst may reexpand over time and become symptomatic again.[8]

Asymptomatic Colloid Cyst

An asymptomatic colloid cyst does not necessarily warrant treatment. If there is hydrocephalus, all surgeons would agree that surgery is warranted, but if a colloid cyst is found incidentally, then surgery is not necessarily warranted. Colloid cysts that are smaller than 10 mm or more centrally located in the third ventricle are less likely to obstruct the near term. Such colloid cysts may be monitored over time with serial imaging looking for colloid cyst size and location and any evidence of hydrocephalus. There have been infrequent reported cases of colloid cysts, which were followed clinically but caused acute hydrocephalus and death.

Differential Diagnosis

There are other lesions that can appear similar to a colloid cyst on imaging, including:

- Craniopharyngioma

- Ependymoma

- Germinoma

- Giant cell astrocytoma

- Hemorrhage

- Lymphoma

- Meningioma

- Metastasis

- Pilocytic astrocytoma

- Pituitary tumor

Prognosis

Some colloid cysts can be watched for years to decades without any issue. Others can slowly grow in size or cause subacute or acute hydrocephalus. With complete surgical resection, the prognosis is good, and colloid cysts are rare to recur after complete resection. Rare cases of sudden death have been reported with colloid cysts, which are usually attributed to acute obstructive hydrocephalus.

Complications

Complications of colloid cysts include:

- Hydrocephalus

- Brain herniation

- Death

- Intralesional hemorrhage[10]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients kept on observation should be instructed to report to the nearest emergency department should they develop severe headaches or vomiting.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The CNS colloid cyst is best managed by an interprofessional team, including neurosurgeons, neurologists, radiologists, and neuroscience nurses. When a colloid cyst is diagnosed, the biggest dilemma is managing it. The minimally invasive approaches have less morbidity but a higher recurrence and reoperation rate. Removing a colloid cyst via a craniotomy has the highest up-front surgical risk but may have the lowest recurrence and reoperation rate. The open craniotomy provides more degrees of freedom for access to the colloid cyst. It may be more suitable for larger colloid cysts but does have limitations based on the approach chosen. A thorough discussion should be undertaken with the patient and let him or her decide which approach they favor. Specialty-trained nurses in perianesthesia, operating room, and critical assist in the care monitor patients and report changes in status to the team. An interprofessional team approach will result in good outcomes.