Continuing Education Activity

Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) has revolutionized the approach to and management of many pulmonary and cardiac diseases over the past two decades. This activity reviews the indications, contraindications, and techniques involved in performing video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS) and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in managing patients undergoing this procedure.

Objectives:

- Describe how video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS) is performed.

- Summarize the indications for video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS).

- Review the complications of video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS).

- Outline interprofessional team strategies for enhancing care coordination and communication to optimize the use of video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS) and improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) has revolutionized the approach and management of many pulmonary and cardiac diseases over the past 2 decades. Thoracoscopic inspection of the pleura, while the patient was under local anesthesia, was first performed by Swedish physician Jacobeaus.[1] This procedure was usually performed to evaluate and treat pleural effusions in patients suffering from pulmonary tuberculosis. Before this technique, the standard approach to a thoracic pathology was a thoracotomy. A breakthrough in technology, which ultimately resulted in the advancement of all forms of minimal access surgery, was the development of fiber-optic light. The number of VATS applications have grown over the decades as technological advancements made such procedures safer for the elderly and frail patients. VATS has multiple advantages over traditional thoracotomy including less postoperative pain, shorter hospital lengths of stay, earlier recovery of respiratory function especially in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and the elderly and overall reduced cost.[2][3][4]

Anatomy and Physiology

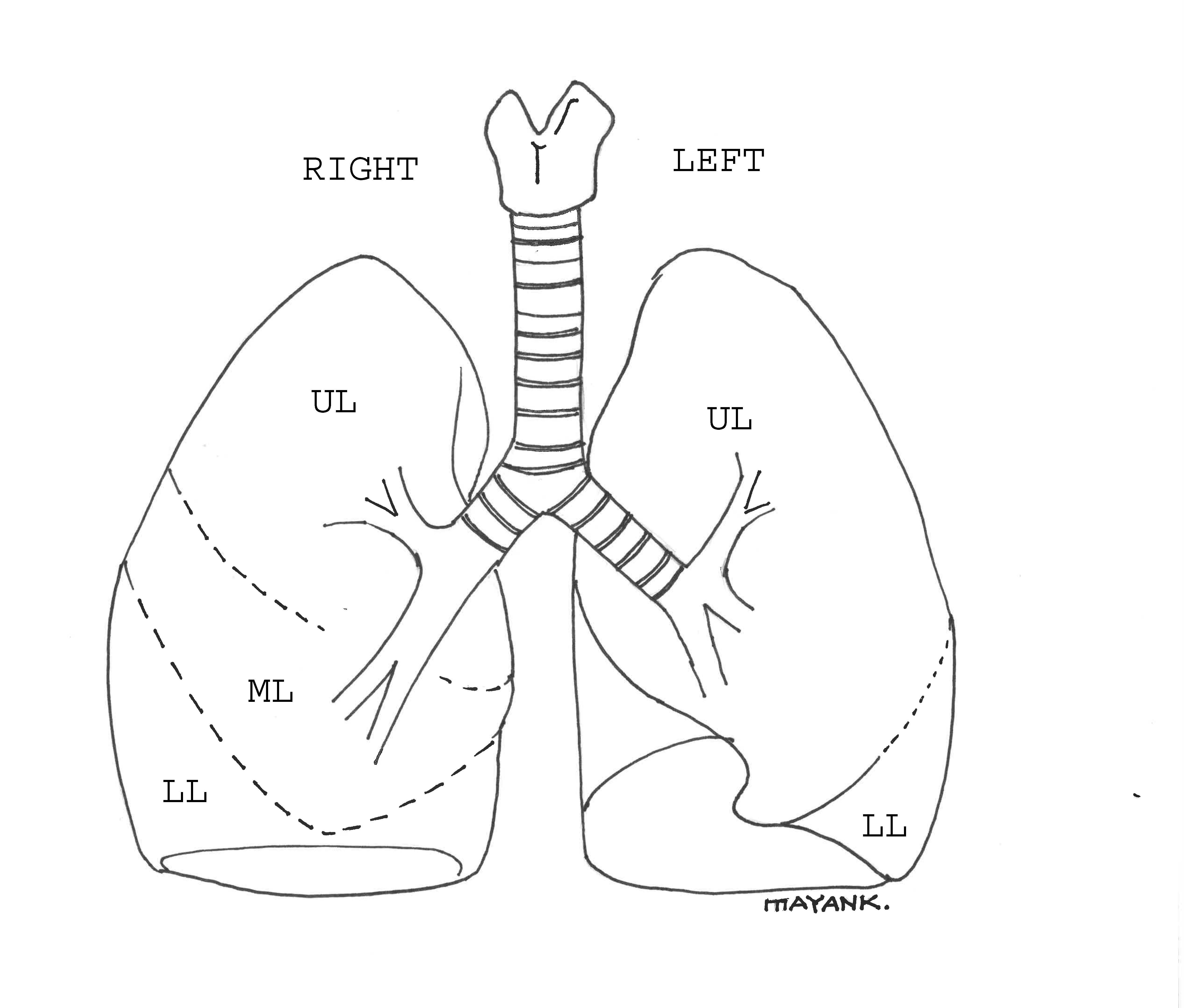

The adult trachea is about 15 cm long. It extends from the lower end of the cricoid cartilage (C6 level) and divides into the right and left main bronchus at the level of T5. The right bronchus is broader and more in line with the trachea. It divides into the upper, middle, and lower lobe branches. The left bronchus is more horizontal and divides into upper and lower branches. The lung lobes are subdivided into bronchopulmonary segments, each supplied by a segmental artery and a segmental bronchus. The veins lie between these segments. It is important for the surgeon to be aware of these surgical units of the lung.

The surgery is usually performed by making incisions in the intercostal space. The incisions are parallel to the long axis of the intercostal space. The surgeon must take care that these incisions are in the center of the space to avoid injury to the intercostal nerves that run in a groove at the lower border of the ribs.

Indications

Diagnostic

- Mediastinal lymph node biopsy

- Pleuroscopy/pleural biopsy

- Tissue/lymph node biopsy for lung cancer

- Chest wall biopsy

- Cancer staging

Therapeutic

- Pulmonary resection (most commonly for lung cancer)

- Pulmonary bleb/bullae resection

- Pleural drainage (pneumothorax, hemothorax, empyema)

- Pericardial effusion drainage

- Mechanical/chemical pleurodesis

- Excision/biopsy of mediastinal masses and nodules

- Excision of esophageal diverticulum/esophagectomy

- Thoracic duct ligation

- Sympathectomy

- Chest wall tumor resection

- Thoracoscopic laminectomy

- Spinal abscess drainage

Contraindications

- Patient unable to tolerate lung isolation/dependence on bilateral ventilation

- Intraluminal airway mass (making double lumen tube (DLT) placement difficult)

- Severe adhesions in the pleural cavity/pleural symphysis

- Coagulopathy

- Hemodynamic instability

- Severe hypoxia

- Severe COPD

- Severe pulmonary hypertension

Equipment

- Fiber-optic thoracoscope, high-resolution video camera

- A light source (preferably high light output) and cable

- Camera

- Image processor

- Monitors

- Scissors

- Hook

- Trocar

Operating Room Setup

The VATS approach requires an operating room setup that allows the thoracic surgeon the potential to convert to an open thoracotomy if necessary. Standard operating room setup for a VATS includes 1 monitor set up on each side of the operating table. There may be an additional screen present in the room for academic purposes and for viewing by other staff in the room.

Usually, the surgeon and the assisting surgeon stand on the anterior aspect of the patient. The anesthesiologist is positioned at the head end of the table. The scrub nurse stands opposite the assistant surgeon across the table. Monitors positioned on both sides of the table allow visualization of the surgery to all people present in the operating room.

Personnel

- Surgeon

- Assisting surgeon

- Anesthesiologist

- Scrub nurse

- Surgical technologist

Preparation

Pre-operative Evaluation

Patient selection plays a key role in successful surgical outcomes. A detailed preoperative examination with a focus on the cardiac and respiratory function is essential to ensure that the selected candidates will tolerate one-lung ventilation (OLV). Preoperative ASA physical status assessment, spirometry, plethysmography, diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) measurement, computed tomography (CT), and cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) should be reviewed.

Preoperative assessment is aimed at assessing lung mechanics (FEV1, MVV, FVC, RV/TLC ratio), parenchymal function (DLCO, PaO2, PaCO2), and cardiopulmonary reserve (VO2 max, exercise tolerance).

The predicted postoperative FEV1 (ppo FEV1%) is a commonly used predictor of postoperative pulmonary reserve. An FEV1 greater than 60% generally suggests that a patient will tolerate an anatomic lobe resection. In case FEV1 is less than 60%, a ventilation-perfusion (VQ scan) scan may be used to calculate the ppo FEV1. A ppo-FEV1 greater than 35%-40% is a good predictor of adequate post-operative pulmonary reserve and surgery may proceed. An FEV1 less than 30% suggests postoperative ventilator or supplemental oxygen dependence[5].

Another common indicator of pulmonary reserve is the diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO). DLCO is a measure of the rate of diffusion of carbon monoxide particles across the alveolar membrane. A DLCO greater than 40% is a good marker for adequate post-operative pulmonary reserve.

For cases in which FEV1 and DLCO are borderline, cardiopulmonary exercise testing is used to predict the reserve of the entire cardiopulmonary axis. Maximal oxygen consumption (VO2) is calculated. A VO2 greater than 10ml/min/kg is required to proceed with surgery[6].

A complete blood count may reveal polycythemia due to pulmonary diseases or an elevated white cell count suggestive of infection or inflammation. Chest x-ray and CT scan provide relevant anatomical details required for the relevant procedure. Arterial blood gases may help identify patients at increased risk of postoperative complications. Patients with PaCO2 greater than 50 mmHg or PaO2 less than 60 mmHg are vulnerable.

Preoperative optimization of patients undergoing VATS may also include smoking cessation, treatment of underlying infections and pulmonary rehabilitation.

Technique or Treatment

Patient Positioning

VATS requires most patients to be in a lateral decubitus position. This is accompanied by arching the table which helps to separate the ribs for better surgical access. This also helps by to relieve any pressure on the intercostal nerves. The lateral decubitus position provides adequate access to most thoracic structures which include the lungs, pleura, esophagus, pericardium amongst other mediastinal structures. Care must be taken at all times to avoid nerve injury by adequately padding pressure points.

The lateral decubitus position, general anesthesia, mechanical ventilation, neuromuscular blockade, and surgical retraction alter the physiology of the lungs under anesthesia as compared to the awake position. Oxygenation will mostly depend on the blood flow directed to the non-ventilated lung (intrapulmonary shunt). Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction which reduces perfusion to the non-ventilated lung reduces the shunt fraction. Any hypoxemia that may develop during the surgery may be managed by increasing FiO2 to 100%. The anesthesiologist may revert to 2 lung ventilation if a rise in FiO2 is unable to correct hypoxemia. Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 5-10 cmH2O may be used on the side of the ventilated lung to increase oxygenation. Small increases in PEEP is recommended to select the minimum effective PEEP as high airway pressures may decrease perfusion to ventilated areas increasing shunted blood to non-ventilated ones. Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) must be avoided as far as possible as this makes surgery difficult on the operative side.

One-Lung Ventilation

VATS is performed under general anesthesia, usually with OLV. Neuromuscular blockade and controlled ventilation are mandatory during OLV with the goal of maintaining adequate oxygenation and a CO2 partial pressure similar to double lung ventilation. Minute ventilation is ideally maintained with lower tidal volumes (5-7 ml/kg) and higher respiratory rates [7] [8]with a peak inflation pressure of less than 35 cm H2O. OLV facilitates surgical procedures on the hemithorax by intentionally collapsing the nondependent lung. This results in the creation of an intrapulmonary Right-to-Left shunt leading to the widening of the Alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient which may manifest as hypoxemia. The techniques used to achieve OLV may involve the use of DLTs, single lumen tubes (SLTs) with built-in bronchial blockers and with separate bronchial blockers.

The use of DLTs provides the ability to ventilate either lung independently or simultaneously. DLT placement requires a special technique, and its position is best confirmed with a fiberoptic bronchoscope. Tube position must be reconfirmed after final positioning of the patient for the procedure as they are prone to malpositioning and displacement.

SLTs with bronchial blockers may be used in place of DLTs. Bronchial blockers have a high-volume/low-pressure cuff. The major advantage of the use of an SLT with a bronchial blocker is that it does not need to be replaced post-procedure in case the patient needs to remain intubated. Bronchial blocker placement is done under fiberoptic visualization. As stated previously with DLTs, bronchial blockers also require reconfirmation of positioning after placing the patient in the lateral decubitus position.

Alternatively, apneic oxygenation or high-frequency positive pressure ventilation may be used for thoracic surgeries. These techniques are limited in their usage due to progressive respiratory acidosis and interference with surgery due to mediastinal bounce.

The most common reason for hypoxemia in OLV is shunting. Its incidence has been reported to be up to 5%.[9] A thorough examination of the anesthetic circuit and machinery is the first recommended step. Any hypoxemia that may develop during the surgery should be managed by increasing FiO2 to 100%. The dependent lung must be suctioned. The anesthesiologist may revert to 2-lung ventilation if a rise in FiO2 is unable to correct the hypoxemia. A recruitment maneuver followed by the application of PEEP may be used on the side of the ventilated lung to increase oxygenation. CPAP must be avoided as far as possible as this makes surgery difficult on the operative side.

Surgical Technique

The standard VATS procedure involves using 3 to 4 incisions made in a triangular configuration for scope and instrument insertion.[10] Alternatively, VATS with a single port has also been described.[11]

- The patient is administered anesthesia in the supine position. A DLT is the airway device of choice for most procedures.

- After DLT placement, the position of the tube is confirmed with a fiberoptic bronchoscope via the lumen of the DLT. Care is taken to ensure adequate positioning of the cuff.

- After confirming adequate tube and cuff placement, the patient is positioned in the lateral decubitus position with the arm over the head. Arching of the table is done to allow adequate surgical exposure. The position of the DLT is then rechecked after final positioning for the procedure.

- Three incisions are made for the anterior approach. Together they form a triangular configuration with the utility incision at the apex of the triangle.

- The camera is inserted through this incision for the creation of other entry ports safely.

- A port is created to accommodate the camera in the auscultatory triangle.

- A third port is created in the mid-axillary line. This is created at the level of the utility port incision.

- After the creation of the 3 ports, assessment is done using the video thoracoscope.

- Further steps of the surgery are usually guided by the specific procedure to be performed.

- Depending on the surgery performed, 1 or 2 pleural drains, connected to an underwater seal drain are usually placed at the end of surgery.

Post-Operative Care

Post-operative care in VATS is centered on the pillars of pain control, respiratory care, and chest tube management. Restrictive fluid therapy is also a crucial strategy for improving outcomes after surgery.

Pain control is at the apex of post-operative care as adequate analgesia has been shown to hasten recovery and avoid respiratory complications. Thoracotomy has been described as one of the most painful of all operative procedures. Pain control begins intraoperatively and continues into the postoperative period. Pain control is chiefly achieved by a combination of intravenous and regional techniques. Intravenous analgesia in the form of systemic opioids and patient controlled analgesia (PCA) is the mainstay of post-thoracotomy analgesic techniques. NSAIDs have opioid sparing benefits and have an added advantage of not producing respiratory depression. Epidural analgesia and intercostal nerve blocks can also supplement the analgesic regimen. Improved analgesia correlates into better respiratory function in the post-operative period as well.

Complications

- Postoperative air leak

- Post-operative pain

- Hypoxemia

- Atelectasis

- Bleeding

- Wound infection

Clinical Significance

VATS has progressively replaced open thoracotomies in most thoracic surgery centers around the world because of its safety profile in elderly patients, better pain control, faster recovery times, and easier control of bleeding. It has been shown to decrease the length of hospital stay compared to open thoracotomy. Most of this could be attributed to the shorter chest tube duration as reported by some in studies with removal rates of 54% in the VATS group on day 1 as compared to 21% in open thoracotomies.[12] This pattern of fewer complications and lower in-hospital mortality been echoed by other studies on lung cancer patients as well.[13]

Authors have reported significantly lower rates of blood transfusions in the VATS groups when compared to the open thoracotomy groups. They also demonstrate lesser postoperative pain and a better quality of life when compared with traditional thoracotomies.[14]

Long-term survival comparisons in studies have shown no statistical difference in overall 3-year survival in patients undergoing thoracoscopic lobectomy compared with patients undergoing open lobectomy.[15] VATS remains the recommended standard of care by a consensus of experts on management of lobectomies.[16]

The advantages offered by VATS over conventional thoracotomy are:

- Decreased surgery time

- Easier control of bleeding

- Decreased postoperative pain including opioid usage

- Decreased chest tube duration

- Decreased length of hospital stay

- Decreased inflammatory response

- Cosmesis

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Bleeding due to vascular injury is the most dangerous complication during VATS for major pulmonary resection and is the main reason for emergent conversion to open thoracotomy. The surgeon, anesthesiologist and operating room team should be prepared to convert to an open thoracotomy if necessary. Adequate intravenous access should be established before all VATS procedures. VATS with conversion and open thoracotomy were associated with similar early postoperative morbidity and mortality rates. VATS should be preferred to thoracotomy; even in the event of converting to an open procedure since it potentially provides the patient with benefits of a fully VATS-based resection but is not disadvantageous when intraoperative conversion is required.[17]

Because of the surgically induced pneumothorax, patients who have undergone a VATS should be transported to the Post Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU), intensive care unit or a step-down unit with supplemental oxygen. Patients are at a high risk of sudden pulmonary decompensation and postoperative bleeding, therefore the anesthesiologist and the PACU or ICU nurses should have a high index of suspicion and patients should be monitored closely.