Continuing Education Activity

Syphilis is a systemic, bacterial infection caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. Due to its many protean clinical manifestations, it has been named the “great imitator and mimicker.” The origin of syphilis has been controversial and under great debate, and many theories have been postulated regarding this. Syphilis remains a contemporary plague that continues to afflict millions of people worldwide. The infection progresses through four stages and can affect many organ systems. Luckily, the causative organism is still sensitive to penicillin. This activity reviews the cause, pathophysiology, and presentation of syphilis and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

- Review the stages of syphilis.

- Describe the process of diagnosing syphilis.

- Summarize the treatment of syphilis.

- Outline the importance of improving care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by syphilis.

Introduction

Syphilis is a systemic bacterial infection caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. Due to its many protean clinical manifestations, it has been named the “great imitator and mimicker.” The origin of syphilis has been controversial and under great debate, and many theories have been postulated regarding this.

The pre-Columbian theory looked at findings on skeletal markers of syphilis before 1490. However, there is insufficient proof, as evidenced by the DNA and paleopathology findings, to support the existence of syphilis before 1492.

The Columbian and most accepted theory postulates that syphilis came from Europe in the 1490s when Columbus arrived in the New World (America). Syphilis spread when Christopher Columbus arrived in Naples (Italy). After Naples lost the battle to the French troops, this new disease spread across Europe.[1]

Syphilis remains a contemporary plague that continues to afflict millions of people worldwide.

The infection progresses through four stages and can affect many organ systems. Luckily, the causative organism is still sensitive to penicillin.

Etiology

Treponema pallidum was identified as the agent that causes syphilis in 1905 by German scientists, and one year later, the first test to diagnose this infection, the Wasserman test, was developed. Its genome was sequenced in 1998. The Treponema genus is a spiral-shaped bacteria with a rich outer phospholipid membrane that belongs to the spirochetal order. It has a slow metabolizing rate, as it takes an average of 30 hours to multiply.

T. pallidum is the only treponemal agent that causes venereal disease. The other Treponema subspecies cause non-venereal disease that is transmitted via nonsexual contact: Treponema pertenue causes yaws, Treponema pallidum endemicum causes endemic syphilis or bejel, and Treponema carateum causes pinta. All the treponematoses have similar DNA but differ in their geographical distribution and pathogenesis.[2] The only host for the organisms is humans, and there is no animal reservoir.

Syphilis is considered a sexually transmitted disease, as most cases are transmitted through vaginal, anogenital, and orogenital contact. The infection can rarely be acquired via nonsexual contacts, such as skin-to-skin, or via blood transfer (blood transfusion or needle sharing). Vertical transmission occurs transplacentally, resulting in congenital syphilis.

Epidemiology

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) statistics, there were 88,042 reported new diagnoses of syphilis in 2016. Out of all syphilis cases, 27,814 were primary and secondary syphilis. In 2016, most syphilis cases occurred among gays, bisexuals, and other men who have sex with men. Men aged 20 to 29 years have the highest rates of primary and secondary syphilis.

Among sex workers, the worldwide incidence of active syphilis in 2019 was 10.8%.

From 2008 to 2012, rates of congenital syphilis declined, but the incidence in adults increased by 38%. In 2016, 628 cases of congenital syphilis were reported, with rates 8.0-times and 3.9-times higher among infants born to Black and Hispanic mothers, respectively, compared to White-race mothers.

Syphilis is endemic in the developing world and is especially common among those who are poor and have limited access to health care.[3] Promiscuity plays an important role in disease transmission, as syphilis is more common among people with multiple partners.

Syphilis is an important synergistic infection for HIV acquisition and has been closely linked with HIV infections.

The incidence of congenital syphilis has nearly quadrupled between 2015 and 2019.

Pathophysiology

Treponema is a very tiny organism that is invisible on light microscopy. Thus, it is identified by its distinct spiral movements on darkfield microscopy. Outside the body, it does not survive for long.

The classic primary syphilis presentation is a solitary non-tender genital chancre in response to invasion by the T. pallidum. However, patients can have multiple non-genital chancres, such as digits, nipples, tonsils, and oral mucosa. These lesions can occur at any site of direct contact with the infected lesion and are accompanied by tender or non-tender lymphadenopathy. Even without treatment, these primary lesions will go away without scarring. If untreated, primary syphilis can progress to secondary syphilis, with many clinical and histopathological findings.

The clinical manifestations of secondary syphilis result from hematogenous dissemination of the infection and are protean: condyloma lata (papulosquamous eruption), hands and feet lesions, macular rash, diffuse lymphadenopathy, headache, myalgia, arthralgia, pharyngitis, hepatosplenomegaly, alopecia, and malaise. As a result, syphilis has been named the great imitator.

Both primary and secondary lesions resolve without treatment, and the patient enters either an early or latent phase in which no clinical manifestations are present. The infection can only be detected at this stage with serological testing. Some patients in this stage will progress to the tertiary stage, characterized by cardiovascular syphilis, neurosyphilis, and late benign syphilis.[3]

The incubation period is about 20 to 90 days. The organism does invade the central nervous system (CNS) early, but symptoms appear late.

Histopathology

T. pallidum is a slowly metabolizing spirochetal bacterium, requiring an average of 30 hours to multiply, and cannot be cultured on artificial media. Its outer membrane lacks lipopolysaccharides and has few surface-exposed proteins, making it difficult for the immune system to fight the infection. Because of this characteristic, T. pallidum is labeled as a stealth pathogen.

There are many histopathological features of syphilis, such as interstitial inflammation, endothelial swelling, irregular acanthosis, elongated rete ridges, and a vacuolar pattern with lymphocytic infiltration. Silver staining can detect spirochetes anywhere from 30% to 70% but comes with a high rate of false-negative interpretation. Immunohistochemistry has a sensitivity of about 70% for accurately identifying the infection.[4]

History and Physical

Primary syphilis appears 10 to 90 days after exposure to the infection and comprises a painless, indurated ulcer (chancre) at the site of inoculation with the T. pallidum. HIV patients usually develop multiple chancres. These lesions resolve without treatment in 3-6 weeks. Regional lymphadenopathy is common and consists of rubbery lymph nodes.

Secondary syphilis appears 2 to 8 weeks after the disappearance of the chancre and has multiple systemic manifestations that can involve any system and body part. The cutaneous manifestations are also varied (condyloma lata, alopecia, mucous patches, palmar or truncal rash, papulosquamous rash), and because they contain a high load of spirochetes, these lesions are highly contagious.

Untreated primary or secondary syphilis is followed by an early latent phase (one year or less later on) or late latent phase (over one year) and is characterized by positive serologic tests but negative clinical manifestations.

Tertiary syphilis is late symptomatic syphilis that can manifest months or years after the initial infection as cardiovascular syphilis (an aortic aneurysm, aortic valvulopathy), neurosyphilis (meningitis, hemiplegia, stroke, aphasia, seizures, tabes dorsalis), or gummatous syphilis (infiltration of any organ and its subsequent destruction).

Congenital syphilis results from transplacental transmission or contact with infectious lesions during birth and can be acquired at any stage, causing stillbirth or neonatal congenital infection. There are many presentations of congenital syphilis, including nasal cartilage destruction (saddle nose), frontal bossing (olympian brow), bowing of the tibia (saber shins), morbilliform rash, rhinitis (snuffles), sterile joint effusion (Clutton joints), peg-shaped upper central incisors (Hutchinson teeth). Many of the neonates born with congenital syphilis are asymptomatic at birth.[5]

Early signs can manifest up to 48 months as rash, hepatosplenomegaly, fever, bulging fontanels, seizures, or cranial nerve palsies. Those untreated neonates enter a latent period. Routine screening is recommended at the first prenatal visit and during the third trimester and delivery in high-risk women.

Evaluation

Testing strategies for syphilis consist of dark-field microscopy and serological tests. Darkfield examination by microscope allows for direct examination of spirochetes from the mucosal lesion and thus offers an immediate diagnosis if positive but can miss 20% of positive cases, especially if the patient has applied topical antibiotics. The sensitivity of darkfield microscopy tends to decrease over time and

The serological tests are classified as nontreponemal and treponemal. The nontreponemal tests (venereal disease research laboratory test (VDRL) and rapid plasma reagin test (RPR) are screening tests that detect antibodies to cardiolipin in blood and are therefore not specific for syphilis. The VDRL and RPR tests are only positive after the development of the primary chancre. These tests are inexpensive, simple to perform, and are the usual initial screening tests for syphilis. Test results can be quantified and used for tracking the progress of the infection, as a fourfold change in titer would be considered significant. Unfortunately, false-positive tests are relatively common, and nontreponemal tests are not specific for syphilis, so a confirmatory treponemal test is required for a definitive diagnosis.

Positive nontreponemal tests must be confirmed with a treponemal test (fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption assay (FTA-ABS), T. pallidum particle agglutination assay (TP-PA)) that detects specific serum antibodies to T. pallidum. While they turn positive early and are specific, treponemal tests do not match the stage, progression, or severity of the infection. They also are positive for life and, therefore, cannot be used for disease tracking.

Patients with neurologic symptoms should undergo a cerebrospinal (CSF) examination. VDRL testing of the CSF is highly sensitive but not very specific for neurosyphilis, while treponemal testing is highly specific but not very sensitive. Therefore, both tests are frequently needed to confirm the diagnosis.

All patients with syphilis should be tested for other STDs, particularly HIV. Syphilis is also routinely tested during the first trimester of pregnancy. Benzathine penicillin G is administered if the testing is positive, and follow-up testing is scheduled.

Imaging studies depend on the organ involved. A chest X-ray may be the first clue to the presence of an aortic aneurysm. A CT scan can confirm this. An echocardiogram is needed to rule out aortic regurgitation. Long-bone x-rays may be useful in neonates.

Reverse sequence screening is an increasingly used algorithm across US laboratories that use treponemal tests as the initial screening to identify those patients with treated, untreated, or incompletely treated syphilis.[6] Because of a lack of validation of the reverse algorithm, higher rates of false-positive results can be seen, leading to difficulty interpreting these tests and the need for additional confirmatory testing.

Syphilis is a reportable disease.

Summary

A definitive diagnosis of syphilis generally requires at least one positive nontreponemal assay (VDRL, RPR) and a positive treponemal test (FTA-ABS, TP-PA). Only the nontreponemal tests can be used for disease tracking as the treponemal tests are usually positive for life and do not correlate well with disease status or severity. CSF testing may be needed in some cases.

Treatment / Management

Treatment depends on the disease stage.

- Primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis is treated with a single dose of intramuscular (IM) benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units.

- Neurosyphilis is treated with IV penicillin G aqueous 18-24 million units daily for 14 days. An alternative regimen would be procaine penicillin G 2.4 million units IM once daily AND Probenecid 500 mg orally 4 times/day for 10–14 days.

- Tertiary and latent syphilis and HIV-infected patients should be treated with weekly benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units IM for three weeks.

Alternative therapies include doxycycline 100 mg orally (PO) twice daily for 14 days or ceftriaxone 1 to 2 gm IM or intravenously (IV) daily for 10 to 14 days or tetracycline 100 mg PO 4 times for 14 days. Azithromycin is no longer recommended due to reports of resistance.

Patients must be followed post-treatment 6, 12, and 24 months after treatment with a clinical evaluation and serial nontreponemal (VDRL and RPR) testing. In addition, re-examinations at 3 and 9 months are suggested for high-risk individuals. A 4-fold decline in nontreponemal test titers indicates successful treatment, while a fourfold increase from the initial level suggests reinfection or therapy failure.[7][8]

Pregnancy and Syphilis

All pregnant patients should be tested for syphilis at their initial prenatal visit or at their first obstetrical visit, whichever comes first. Pregnant patients who test positive for syphilis should have nontreponemal testing to track their titers. Serological testing is recommended during the third trimester: At 28 weeks, and at delivery for patients who live in geographic areas with a high incidence of syphilis or who are otherwise at high risk (no prenatal care at the time of delivery, history of drug abuse, other STIs, multiple or new sexual partners). Mothers should be tested for syphilis after 20 weeks of gestation in any fetal death. All mothers who test positive for syphilis should also be tested for HIV.

Ultrasonography of the fetus for signs of congenital syphilis is recommended when the disease has been diagnosed during the second half of the mother's pregnancy. Sonographic signs of congenital syphilis include ascites, hepatomegaly, hydrops, and a thickened placenta.[9] Such prenatal signs suggest a higher risk of treatment failure in the fetus.[9] Such pregnant patients are at higher risk of encountering fetal distress, premature labor, or the Jarisch Herxheimer reaction (see below). Fetal monitoring is recommended when starting antimicrobial therapy in pregnant women with syphilis.[10] Pregnant women who develop a Jacob Herxheimer reaction need to be observed closely as it can lead to obstetric complications such as fetal distress and early labor induction. The risk is estimated at about 40%. Despite this risk, treatment of syphilis should not be delayed.

Treating syphilis during pregnancy is the same as for non-pregnant patients based on their stage of infection. A second dose of 2.4 million units of IM benzathine penicillin G administered one week after the initial injection is beneficial in helping prevent congenital syphilis.[11] There is no evidence that treatment with corticosteroids helps minimize complications when treating syphilis during pregnancy. Pregnant women who miss a scheduled dose of therapy by two days or more will need to have their entire treatment repeated.

A fourfold decrease in nontreponemal titers is optimal but may not be achieved prior to delivery, even in properly treated patients. This does not necessarily indicate a treatment failure.[12] However, a fourfold increase in titers present for two weeks or more is likely to be either a treatment failure or reinfection. Followup titers are not recommended prior to two months following treatment.

There are no known acceptable alternatives to penicillin for the treatment of syphilis during pregnancy. Therefore, pregnant women who are penicillin allergic should be skin tested to identify their actual risk and undergo desensitization so they can be treated with penicillin.[13] Alternative medications are not considered adequate. (Doxycycline and tetracyclines should be avoided in the latter stages of pregnancy, there is insufficient data on ceftriaxone and cephalosporins, while azithromycin and erythromycin do not reliably cure the mother and will not adequately treat the fetus.)[14]

Patients with a high titer of primary or secondary syphilis can develop a Jarisch Herxheimer reaction, which is a self-limited immune-mediated response that occurs within 2 to 24 hours of antibiotic treatment and is characterized by high fever, headache, myalgias, and rash.[10] (See below)

Congenital Syphilis

Congenital syphilis can be a diagnostic challenge as maternal antibodies are transferable to the fetus. Such antibodies can persist for 15 months. Clinical signs and symptoms of congenital syphilis include fetal hydrops, hepatosplenomegaly, pseudoparalysis of an extremity, hyperbilirubinemia, jaundice, rhinitis, or a skin rash. Darkfield microscopy and/or PCR testing of any suspicious lesions should be done. Further workup for suspected cases includes x-rays of the long bones, a CBC, and an analysis of CSF fluid for cell count, protein, and a VDRL titer.

Treatment of congenital syphilis is aqueous crystalline penicillin G at 100,000–150,000 units/kg body weight/day. This is given as 50,000 units/kg body weight/dose IV every 12 hours during the first seven days after birth, then every 8 hours for ten days. An alternative regimen is procaine penicillin G 50,000 units/kg body weight/dose IM in a single daily dose for ten days. Ten-day treatment protocols are recommended for neonates with proven syphilis or with moderate to high risk. Lower-risk newborns may be treated with a single dose of benzathine penicillin G 50,000 units/kg body weight/dose IM is an alternative therapy for congenital syphilis if their recommended testing is negative.

Neonates with a positive nontreponemal test (VDRL or RPR) should be retested at least every three months until they become non-reactive. If a baby was not treated as his risk was considered low, his nontreponemal test titers should drop by three months and become non-reactive by six months. If so, no further treatment or evaluation is needed. If the testing still shows positive titers, the infant should be treated as a congenital syphilis neonate and given a 10-day course of penicillin as above.

If CSF titers remain positive after 18 months, retreatment for neurosyphilis is indicated.

Pediatric Syphilis

Older children who test positive serologically for syphilis should have a CBC with differential and a CSF examination for cell count, protein, and a VDRL titer. Other optional tests would include x-rays of the long bones, chest x-ray, liver function studies, abdominal ultrasound, neurological imaging, auditory brain-stem response, and an ophthalmologic evaluation as clinically indicated.

The standard treatment for pediatric syphilis in children is aqueous crystalline penicillin G at 200,000 to 300,000 units/kg body weight/day IV. The medication is administered as 50,000 units/kg body weight every 4–6 hours for ten days. This is followed by a single dose of benzathine penicillin G at 50,000 units/kg body weight (up to a maximum of 2.4 million units).

If there are no clinical manifestations of syphilis and the evaluation is otherwise normal (VDRL of the CSF, CBC, etc.), consideration can be given to treating the child with three weekly doses of IM benzathine penicillin G 50,000 units/kg body weight (up to a maximum of 2.4 million units/IM injection).

Patients with a Penicillin Allergy May Still be Treatable with Penicillin [15]

When specifically tested, most patients (<9%) who report a penicillin allergy actually have it confirmed.[16][17] The vast majority of patients who believe they have a penicillin allergy can safely receive penicillin. This is only significant in a disease like syphilis, where no reasonable alternative exists. Even among those with a well-documented IgE-mediated allergy, about 80% will lose their sensitivity to penicillin after ten years.[18]

Ceftriaxone may be a reasonable alternative to penicillin in selected syphilis cases. Neurosyphilis and at least one case of syphilis in pregnancy have been treated successfully with ceftriaxone.[15][19][20] It crosses the blood-brain barrier as well as the placenta.[21][22] It is safe for the fetus and effective in killing T. pallidum at low serum concentrations.[21][22] Even with the reduced drug levels in the amniotic fluid and fetal serum, the concentration of ceftriaxone is still well above the MIC for T. pallidum.[21][22][23]

- Many patients with a presumed penicillin allergy may not be allergic.

- Skin testing to confirm the penicillin allergy should be considered, as penicillin is still the preferred antimicrobial for syphilis, especially neurosyphilis and pregnancy.

- Skin testing should NOT be performed in patients with a history of severe allergic reactions to penicillin, such as anaphylaxis, toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, interstitial nephritis, or hemolytic anemia.

- If the skin testing is negative, this is usually followed by an oral penicillin challenge with amoxicillin.

- For those who test positive, desensitization by an allergist can be considered, especially during pregnancy and in patients with neurosyphilis, where alternative medications are not recommended.

- Anecdotally, ceftriaxone has been used successfully without incident for the treatment of syphilis and the prevention of congenital syphilis in a pregnant patient with a severe allergic reaction to penicillin.[19]

For further details on treatment, see our companion reference StatPearls articles on "Sexually Transmitted Infections," "Neurosyphilis," and "Congenital Syphilis."[24][25][26]

The Jarisch Herxheimer Reaction

Following initiation of treatment for syphilis with penicillin, especially in the early stages, the dying organisms release toxins that can lead to the Jarisch Herxheimer reaction through cytokine induction. The symptoms include headache, muscle pain, fever, tachycardia, rash, and malaise. The most common symptom is fever, followed by an exacerbation of cutaneous lesions. The reaction usually appears within a few hours of starting treatment and spontaneously resolves within 24 hours without treatment. Patients should be warned about this possible reaction prior to starting therapy and that it is not an allergic response to penicillin.[10]

Patients at highest risk are those with the highest bacterial loads, typically those with primary and secondary syphilis, where over 50% of patients will develop the reaction. Patients with latent syphilis are the least likely to develop a reaction.[10]

Treatment of the Jarisch Herxheimer reaction is mainly supportive. NSAIDs and acetaminophen can help mitigate symptoms but will not prevent the reaction. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha antibodies and steroids may be of some additional help in minimizing symptoms, but their use has not been adequately studied.[10] (See our companion reference StatPearls article on "Jarisch Herxheimer Reaction.")[10]

Preventing Syphilis

Benzathine penicillin should be administered if a person has sex with a known infected individual.

WHO Guidelines

- Benzathine penicillin administered intramuscularly is the treatment of choice.

- Procaine penicillin is the 2nd choice and is administered intramuscularly for 10 to 14 days.

- If penicillin cannot be used, doxycycline, azithromycin, or ceftriaxone are other options.

- Doxycycline is preferred as it is cheap and easy to administer. But it is not recommended for children or pregnant women.

- Azithromycin does not cross the placenta, so the infant must be treated after delivery.

Differential Diagnosis

- Genital herpes

- Behcet syndrome

- Mononucleosis

- Contact or atopic dermatitis

- Lymphoma

- Viral exanthema

- Pityriasis rosea

- Erythema multiforme

- Rocky Mountain spotted fever[3]

Prognosis

The prognosis of syphilis depends on the stage and extent of organ involvement. If left untreated, the organism has significant morbidity and mortality. Patients usually develop cardiovascular and CNS syphilis, which are fatal if untreated. Congenital syphilis is associated with spontaneous abortions, stillbirth, and fulminant pulmonary hemorrhage in neonates. Without treatment during pregnancy, syphilis is almost always passed on to the fetus.

Complications

Untreated syphilis infection can lead to irreversible neurological and cardiovascular complications. Depending on the stage, neurosyphilis can manifest as meningitis, stroke, cranial nerve palsies during early neurosyphilis or tabes dorsalis, dementia, and general paresis during late neurosyphilis. Cardiovascular syphilis is also a result of tertiary syphilis and can manifest as aortitis, aortic regurgitation, carotid ostial stenosis, or granulomatosis lesions (gummas) in various body organs.

Untreated syphilis affects the course of HIV infection with higher virus replication rates and lower CD4 counts. There is also a faster rate of progression to late syphilis.[8] Primary and secondary syphilis during pregnancy leads to neonatal infections with congenital syphilis and adverse pregnancy outcomes if not identified promptly and treated properly.

Consultations

It is recommended for the primary physician to consult with an infectious disease specialist regarding confirmation of the disease, treatment, and follow-up. Pediatric infectious disease specialists are best suited to manage congenital syphilis.

Pearls and Other Issues

Patients with neurosyphilis and syphilis during pregnancy who are penicillin allergic should consider skin testing with a follow-up oral amoxicillin challenge unless contraindicated. Penicillin desensitization can be considered in selected individuals.

Always test for HIV and other STDs as appropriate in syphilis patients.

Remember that a positive result from both a nontreponemal and a treponemal test is required to make a definitive diagnosis of syphilis.

Nontreponemal tests (VDRL, RPR) can be quantified and used for disease tracking, while treponemal tests are typically positive for life and do not correlate well with disease status.

Syphilis can cause a gamut of systemic manifestations, and for this reason, it has been called the "great mimicker." Despite its discovery centuries ago, it continues to be a significant public health problem, especially in poorer populations in undeveloped countries with poor healthcare systems. Because of its varied manifestations, the diagnosis can be challenging. Physicians need to maintain an increased level of suspicion for screening high-risk populations, such as men who have sex with men, pregnant women with syphilis, sex trade workers, and HIV-infected patients. Penicillin remains the primary treatment based on the stage of infection and whether CNS involvement occurs.

Treated patients need to be followed up with non-treponemal antibody titers (VDRL, RPR) to evaluate the response to therapy.

For more details on specific syphilis complications, please consult our companion reference StatPearls articles on:

- "Congenital Syphilis"[26]

- "Jarisch Herxheimer Reaction"[10]

- "Neurosyphilis" [25]

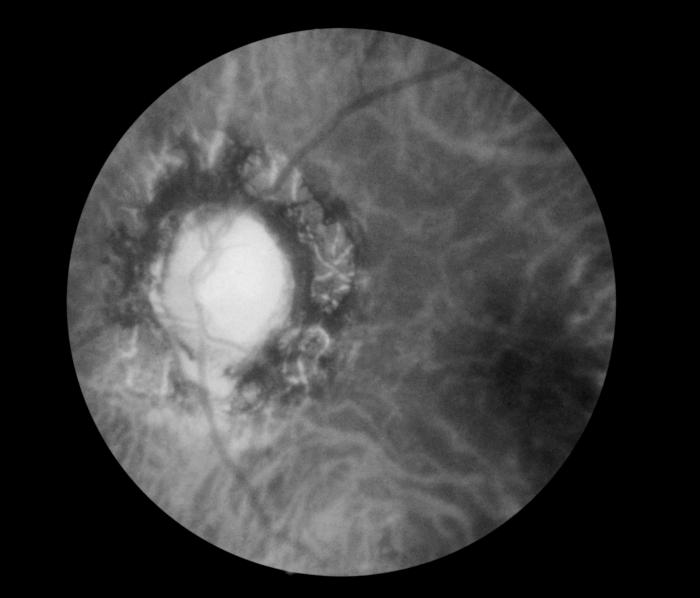

- "Syphilis Ocular Manifestations"[27]

- "Tabes Dorsalis"[28]

- "TORCH Complex"[29]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Once the diagnosis of syphilis has been made, the management is with an interprofessional team since the infection can affect almost every organ in the body. These patients need close follow-up by the cardiologist, neurologist, dermatologist, internist, primary care, ophthalmologist, obstetrician, gynecologist, urologist, and infectious disease expert. The patient must be followed by an infectious disease specialist, gynecologist, urologist, or primary care to ensure that the treatment works and the patient is compliant with therapy. The patient's partner should be examined and treated if necessary. If a patient with syphilis is or becomes pregnant, close follow-up with an obstetrician is highly recommended.[30][31]

Patient education is vital, and the public health team, including clinicians, nurses, and pharmacists, should counsel patients about safe sexual practices and the potential harm of IV drug use which can be mitigated by using clean needles. Today, there are needle exchange programs in many cities.

Nurses must also educate the public on the importance of regular screening for sexually transmitted diseases. The use of barrier protection (condoms) is highly recommended. Pharmacists should educate patients that there are effective treatments for STDs, and the earlier the condition is treated, the better the outcomes, as well as reiterating appropriate prevention strategies.

Every interprofessional team member must keep meticulous records of every intervention and interaction with the patient so that everyone involved in care has access to the same updated patient information. They must also be prepared to communicate to any other team member if they note any concerns, including status changes, non-compliance with therapy, adverse events, or anything else that may warrant further attention. Only through close collaboration with an interprofessional team can the incidence and morbidity of infections like syphilis be lowered.

The outlook for most patients who are compliant with treatment is good, but those who delay or fail to comply with therapy can develop life-threatening complications.[32][33]