Continuing Education Activity

Sea urchin envenomation occurs when a sea urchin spine penetrates the soft tissue of the victim. Frequently spines break off and remain in the soft tissue, causing tenosynovitis, granulomas, or systemic symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, paresthesias, weakness, abdominal pain, syncope, hypotension, and respiratory distress. This activity examines how to properly evaluate and manage sea urchin envenomation and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in caring for affected patients.

Objectives:

- Identify the epidemiology of sea urchin envenomation.

- Describe the evaluation of sea urchin envenomation.

- Outline the management options for sea urchin envenomations.

- Explain interprofessional team strategies to enhance the prevention and management of sea urchin envenomation in order to improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

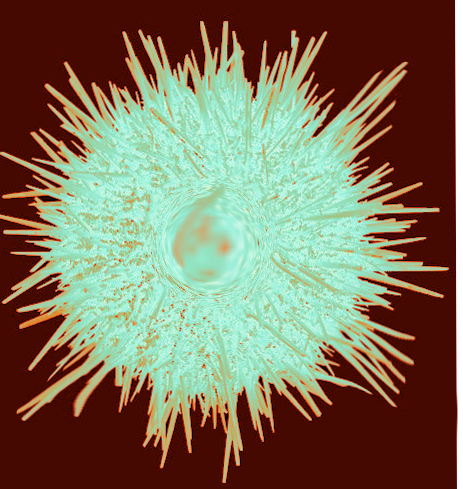

Sea urchins are part of the phylum Echinodermata which also includes starfish. Sea urchins have globular bodies covered by calcified spines. The spines are either rounded at the tip or hollow for envenomation. The also can have pedicellariae that can grasp and envenomate, typically with more venom than in the spines. Echinoderms possess a distinctive endoskeletal tissue called stereom, which is composed of calcite organized into a mesh-like structure, in addition to dermal cells and fibers. Stereom forms structural elements that can embed into human tissue as spines. When stepped on, these spines cause painful puncture wounds with immediate pain, bleeding, and edema. They can cause severe muscle ache which can last up to 24 hours.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Sea urchin envenomation occurs when a spine penetrates soft tissue. Frequently spines can break off into the victim. A retained spine can cause tenosynovitis or a granuloma.[4] It can also cause systemic symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, paresthesias, weakness, abdominal pain, syncope, hypotension, and respiratory distress.[1]

Epidemiology

Echinoderm envenomation does not represent a significant public health problem although little epidemiologic data are available.

There are many species of sea urchins in all oceans. Marine envenomation by sea urchins can happen to swimmers, fishermen, divers, surfers. Most incidents of envenomation occur in tropical and subtropical waters, and are most common among divers, especially in shallow water near rocky shores. The American Association of Poison Control Centers’ 2010 and 2011 annual reports document approximately 1800 aquatic exposures in the United States yearly, with approximately 500 treated.[5]

Pathophysiology

Urchin venoms are comprised of various toxins including glycosides, hemolysins, proteases and can be mixtures of high-molecular-weight proteins and low-molecular-weight compounds such as histamine, serotonin, and bradykinin.[1]In many cases, envenomation leads to mast cell degranulation, disruption of cell metabolism, interference with neuronal transmissions, and myocardial depression. Subsequently, envenomation can cause significant pain, dermatitis, paralysis, cardiovascular collapse, and respiratory failure.[5]

Histopathology

Contact with sea urchin spines and envenomation may trigger a vigorous inflammatory reaction and can proceed to tissue necrosis.

Toxicokinetics

Urchin venoms contain steroid glycosides, hemolysins, proteases, serotonin, and cholinergic substances.[1]

History and Physical

A typical history will involve an individual who accidentally stepped on a sea urchin spine while in shallow water within the past 24 hours. The patient will describe an immediate, incapacitating burning pain which localizes to the puncture wound. This burning may last several hours, and wound pressure exacerbates it. There may be systemic symptoms such as nausea and vomiting, paresthesias, weakness, abdominal pain, syncope, hypotension, and respiratory distress. On physical exam, there may be bleeding, edema, erythema, and warmth at and surrounding the puncture site. A spine may or may not be visible. In some instances, there may exist dark blue or black pigmentation (temporary tattooing) to surrounding tissues from dark-colored spines.

Following the severe burning pain, localized edema, erythema, warmth, and bleeding may develop. In severe cases, nausea, vomiting, paresthesias, muscular paralysis, and respiratory distress may occur. Delayed sequelae include wound tattooing as the pigment is leeched from dark-colored spines into the surrounding tissue, synovitis if the spine violates a joint space, secondary wound infection, or granuloma formation if there is retention of foreign material.

Evaluation

There are no specific laboratory tests indicated in the management of echinoderm envenomation.

Radiography, ultrasound, computed tomography, or MRI may be helpful in spine localization and removal.

Treatment / Management

Removal of all visible spines should be prompt, as they can continue to cause envenomation even when detached from the urchin body. The wounded area should be submerged in hot water (40 C - 46 C), as tolerated by the patient, for 30-90 minutes, or until there is substantial pain relief. Care should be taken not to cause thermal burns. Oral analgesia should also is a consideration. Tetanus vaccine status should be updated. Occasionally, local anesthetic infiltration or a nerve block may be a useful adjunct to pain relief. Wounds are to be irrigated, debrided, and explored for retained spines. If spines are easily visualized and reached, they should be removed. Even in the absence of a spine, a dark discoloration may indicate dye in the tissues. If this is the case, the discoloration should resolve within 48 hours. If spines have entered a joint or are close to neurovascular structures, the joint may require splinting, and an appropriate consult to surgery made. If the patient experiences reactive neuropathy, it may respond to a systemic corticosteroid. In addition to the initial pain and tissue damage, secondary infections are common. If there are some retained spines, granulomas may develop, which may require excision. Arthritis from retained spines may also develop, which may require synovectomy.[1][5]

No antivenoms are currently available for Echinoderm species. Treatment is supportive.

Prophylactic antibiotics are typically not indicated, except in persons with deep wounds, persons with significant morbidities, or those who are immunocompromised. Once the presence of an infection is established, therapy must be instituted, to include coverage for potential marine pathogens. Common organisms associated with marine trauma include Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species, Vibrio vulnificus, and Mycobacterium marinum.

If antibiotics coverage is warranted, treatment should be for 7-14 days duration. Oral Ciprofloxacin 500 mg PO BID, Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 160/800 mg PO BID, or Doxycycline, 100 mg PO BID can be used.[1]

Broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics are indicated for severe wound infections or sepsis.

Differential Diagnosis

Cellulitis - Inflammation of skin and soft tissue following an Echinoderm sting may resemble cellulitis. A history of stepping on a spine and immediate pain following the event will rule out simple cellulitis.

Contact Dermatitis - If the patient presents several days after the inciting event with a more progressive infection, it can resemble the pustular appearance of contact dermatitis. A history of stepping on a spine in the ocean should rule out this diagnosis.

Anaphylaxis - Echinoderm stings can cause systemic symptoms that can mimic anaphylaxis. On initial presentation, if an unstable patient is unable to provide a history, treatment is supportive.

Stingray and Starfish envenomation are also differentials.

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

Management is supportive, and there is no specific toxicity or side effects, other than potential antibiotic side effects.

Prognosis

Local and systemic effects are both possible following echinoderm envenomation. However, there is no clear link between echinoderm envenomation and death found in the current literature.

Complications

Systemic symptoms such as cardiovascular collapse and cellulitis are the most common complications.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

If surgical debridement is needed, the standard of care should apply.

Consultations

If the spine has entered a joint or is close to a neurovascular structure, the patient should receive a surgical referral.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Advise patients to be vigilant and alert of their surrounding, especially when they are swimming or walking in a large body of water. Most injuries caused by sea urchins result from inadvertently stepping on a spine. Wading barefoot, especially at night, should be avoided. Shoes and diving gear offer some protection but are easily penetrable by a sharp spine.

Pearls and Other Issues

Urchin toxins are heat labile and therefore hot water immersion is very effective in neutralizing these toxins and reducing the pain.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A vital step in the appropriate treatment of an echinoderm envenomation is the identification of the actual event. Upon completion of this step, initiation of proper therapy can begin. It is imperative for physicians, nurses, and all caregivers to communicate effectively and to establish roles, to provide timely management of this ailment to the patient.