[1]

Sliwicki AL, Orringer K. Corneal Abrasions. Pediatrics in review. 2023 Jun 1:44(6):343-345. doi: 10.1542/pir.2022-005537. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 37258882]

[2]

Aalam W, Barry M, Alharbi M, Tamur S, Wazzan A, Edward DP. Diagnosis and Management of Corneal Abrasion Perception of (Primary Health Care Physicians and Emergency Physicians) and its Determinants in Saudi Arabia - A Survey. Middle East African journal of ophthalmology. 2021 Jul-Sep:28(3):151-158. doi: 10.4103/meajo.meajo_96_21. Epub 2021 Dec 31

[PubMed PMID: 35125796]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[3]

Wipperman JL, Dorsch JN. Evaluation and management of corneal abrasions. American family physician. 2013 Jan 15:87(2):114-20

[PubMed PMID: 23317075]

[4]

Ambikkumar A, Arthurs B, El-Hadad C. Corneal foreign bodies. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2022 Mar 21:194(11):E419. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.211624. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 35314442]

[5]

Lin YB, Gardiner MF. Fingernail-induced corneal abrasions: case series from an ophthalmology emergency department. Cornea. 2014 Jul:33(7):691-5. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000133. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 24831196]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[6]

Lim CHL, Stapleton F, Mehta JS. Review of Contact Lens-Related Complications. Eye & contact lens. 2018 Nov:44 Suppl 2():S1-S10. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000000481. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29373389]

[7]

Hegarty DM, Hermes SM, Morgan MM, Aicher SA. Acute hyperalgesia and delayed dry eye after corneal abrasion injury. Pain reports. 2018 Jul-Aug:3(4):e664. doi: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000664. Epub 2018 Jun 20

[PubMed PMID: 30123857]

[8]

Ahmed F, House RJ, Feldman BH. Corneal Abrasions and Corneal Foreign Bodies. Primary care. 2015 Sep:42(3):363-75. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2015.05.004. Epub 2015 Jul 31

[PubMed PMID: 26319343]

[10]

Ruffin M, Brochiero E. Repair Process Impairment by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Epithelial Tissues: Major Features and Potential Therapeutic Avenues. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2019:9():182. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00182. Epub 2019 May 31

[PubMed PMID: 31214514]

[11]

Miller DD, Hasan SA, Simmons NL, Stewart MW. Recurrent corneal erosion: a comprehensive review. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2019:13():325-335. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S157430. Epub 2019 Feb 11

[PubMed PMID: 30809089]

[12]

Bourges JL. Corneal dystrophies. Journal francais d'ophtalmologie. 2017 Jun:40(6):e177-e192. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2017.05.003. Epub 2017 Jun 3

[PubMed PMID: 28583694]

[13]

Lai SC, Wang CW, Wu YM, Dai YX, Chen TJ, Wu HL, Cherng YG, Tai YH. Rheumatoid Arthritis Associated with Dry Eye Disease and Corneal Surface Damage: A Nationwide Matched Cohort Study. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2023 Jan 15:20(2):. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20021584. Epub 2023 Jan 15

[PubMed PMID: 36674338]

[14]

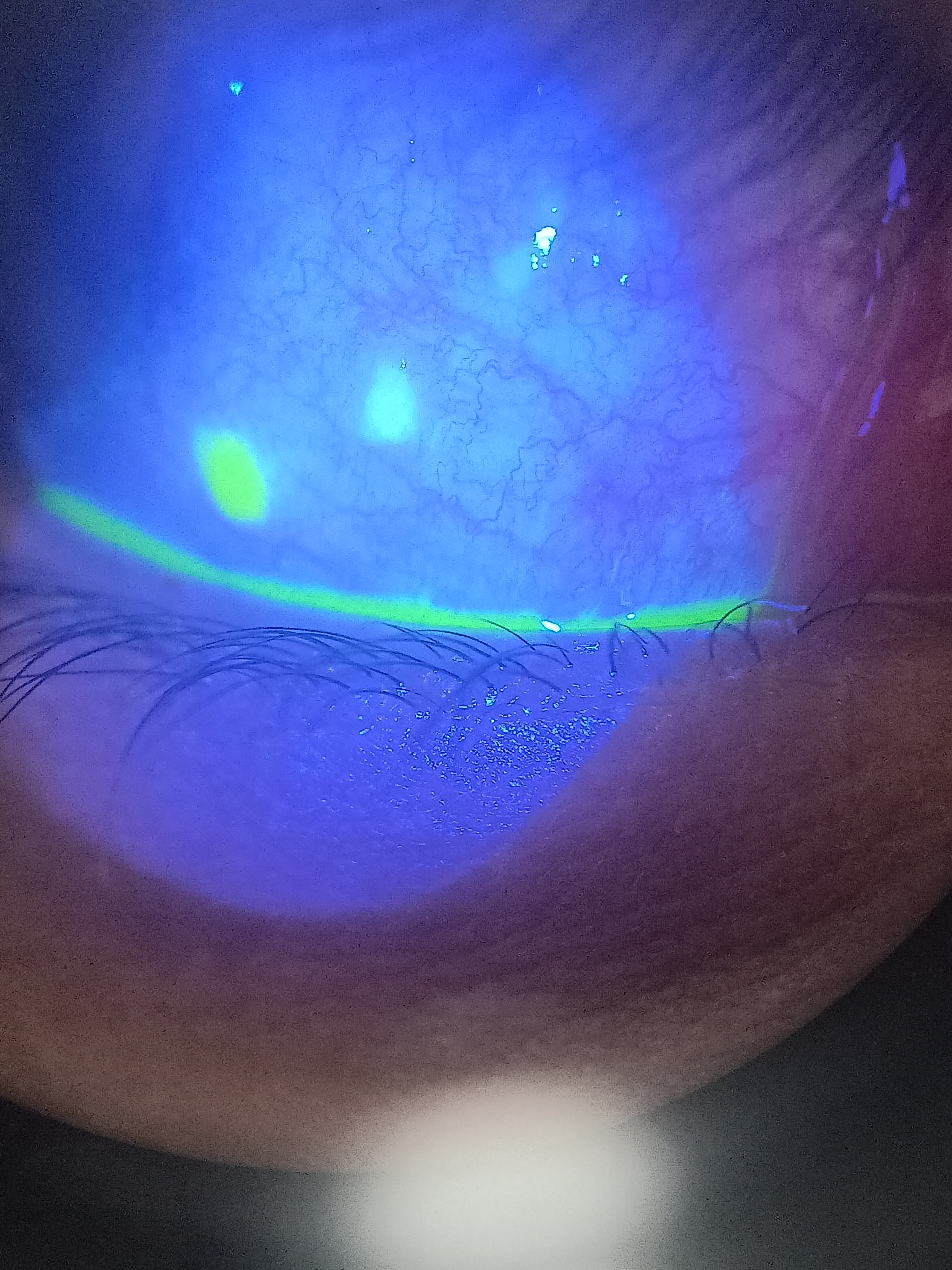

Watson SL, Leung V. Interventions for recurrent corneal erosions. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018 Jul 9:7(7):CD001861. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001861.pub4. Epub 2018 Jul 9

[PubMed PMID: 29985545]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[15]

Lin SR, Aldave AJ, Chodosh J. Recurrent corneal erosion syndrome. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2019 Sep:103(9):1204-1208. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2019-313835. Epub 2019 Feb 13

[PubMed PMID: 30760455]

[16]

Shields T, Sloane PD. A comparison of eye problems in primary care and ophthalmology practices. Family medicine. 1991 Sep-Oct:23(7):544-6

[PubMed PMID: 1936738]

[17]

McGwin G Jr, Xie A, Owsley C. Rate of eye injury in the United States. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2005 Jul:123(7):970-6

[PubMed PMID: 16009840]

[19]

McGwin G Jr, Owsley C. Incidence of emergency department-treated eye injury in the United States. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2005 May:123(5):662-6

[PubMed PMID: 15883286]

[20]

Jayamanne DG. Do patients presenting to accident and emergency departments with the sensation of a foreign body in the eye (gritty eye) have significant ocular disease? Journal of accident & emergency medicine. 1995 Dec:12(4):286-7

[PubMed PMID: 8775960]

[21]

Stapleton F, Keay L, Jalbert I, Cole N. The epidemiology of contact lens related infiltrates. Optometry and vision science : official publication of the American Academy of Optometry. 2007 Apr:84(4):257-72

[PubMed PMID: 17435509]

[22]

Schornack MM, Nau CB, Harthan J, Shorter E, Nau A, Fogt J. Survey-Based Estimation of Corneal Complications Associated with Scleral Lens Wear. Eye & contact lens. 2023 Mar 1:49(3):89-91. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000000972. Epub 2023 Jan 4

[PubMed PMID: 36602410]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[23]

Lee SY, Kim YH, Johnson D, Mondino BJ, Weissman BA. Contact lens complications in an urgent-care population: the University of California, Los Angeles, contact lens study. Eye & contact lens. 2012 Jan:38(1):49-52. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0b013e31823ff20e. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 22157395]

[24]

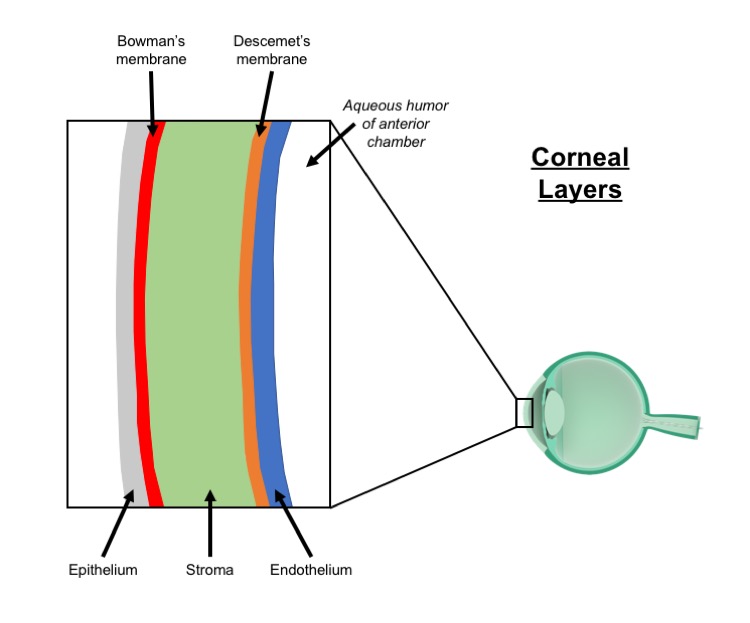

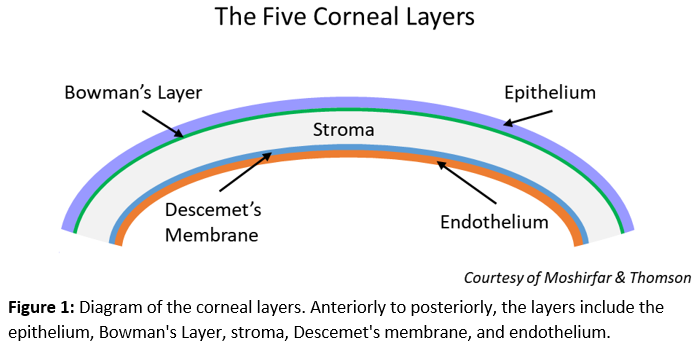

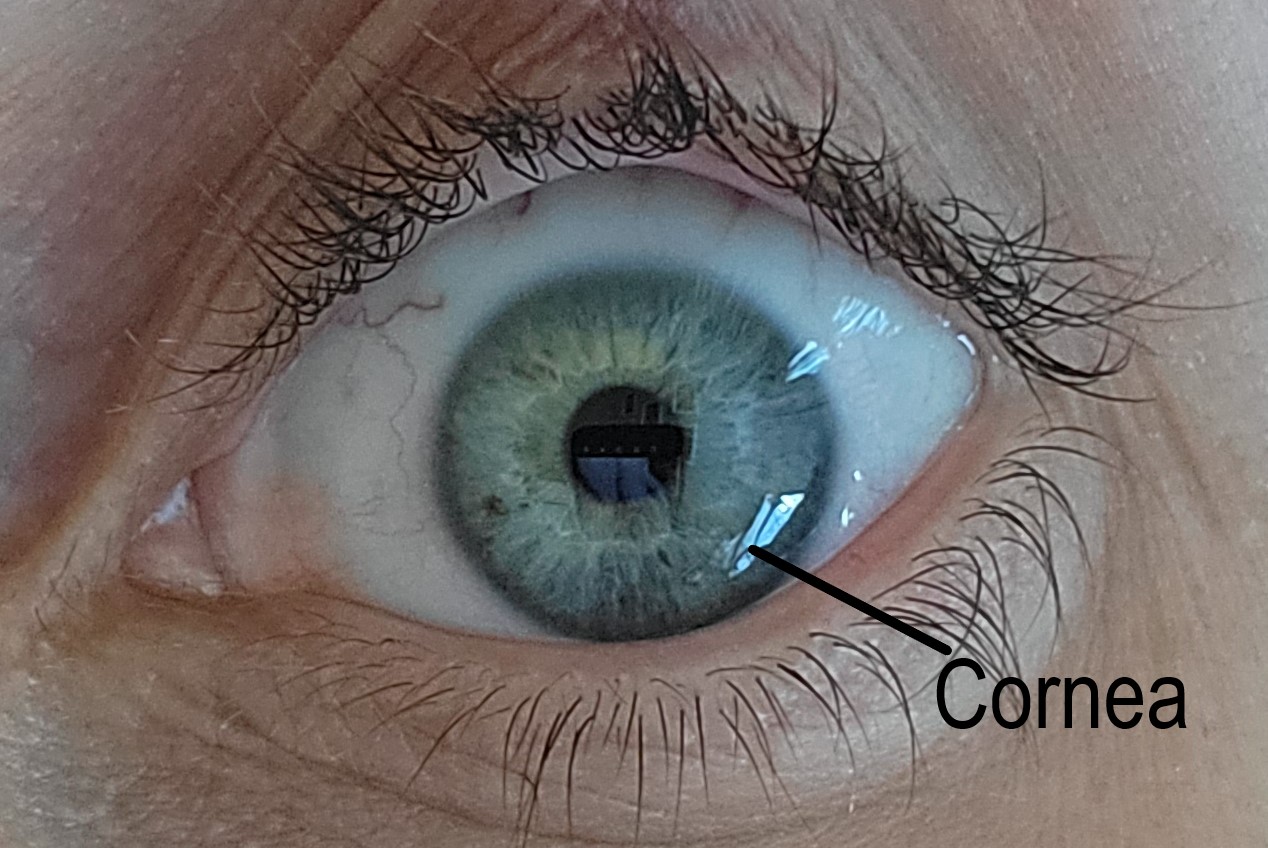

Sridhar MS. Anatomy of cornea and ocular surface. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Feb:66(2):190-194. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_646_17. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29380756]

[25]

Feizi S, Jafarinasab MR, Karimian F, Hasanpour H, Masudi A. Central and peripheral corneal thickness measurement in normal and keratoconic eyes using three corneal pachymeters. Journal of ophthalmic & vision research. 2014 Jul-Sep:9(3):296-304. doi: 10.4103/2008-322X.143356. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25667728]

[26]

Ruan Y, Jiang S, Musayeva A, Pfeiffer N, Gericke A. Corneal Epithelial Stem Cells-Physiology, Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Options. Cells. 2021 Sep 3:10(9):. doi: 10.3390/cells10092302. Epub 2021 Sep 3

[PubMed PMID: 34571952]

[27]

Rocha-de-Lossada C, Torras-Sanvicens J, Peraza-Nieves J. Corneal epithelial cells division assessed by scanning electron microscopy. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2020 Oct:68(10):2252. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1214_20. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 32971670]

[28]

Leong YY, Tong L. Barrier function in the ocular surface: from conventional paradigms to new opportunities. The ocular surface. 2015 Apr:13(2):103-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2014.10.003. Epub 2015 Jan 13

[PubMed PMID: 25881994]

[29]

Altshuler A, Amitai-Lange A, Tarazi N, Dey S, Strinkovsky L, Hadad-Porat S, Bhattacharya S, Nasser W, Imeri J, Ben-David G, Abboud-Jarrous G, Tiosano B, Berkowitz E, Karin N, Savir Y, Shalom-Feuerstein R. Discrete limbal epithelial stem cell populations mediate corneal homeostasis and wound healing. Cell stem cell. 2021 Jul 1:28(7):1248-1261.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2021.04.003. Epub 2021 May 12

[PubMed PMID: 33984282]

[30]

Tavakkoli F, Eleiwa TK, Elhusseiny AM, Damala M, Rai AK, Cheraqpour K, Ansari MH, Doroudian M, H Keshel S, Soleimani M, Djalilian AR, Sangwan VS, Singh V. Corneal stem cells niche and homeostasis impacts in regenerative medicine; concise review. European journal of ophthalmology. 2023 Jul:33(4):1536-1552. doi: 10.1177/11206721221150065. Epub 2023 Jan 5

[PubMed PMID: 36604831]

[31]

Liu CY, Kao WW. Corneal Epithelial Wound Healing. Progress in molecular biology and translational science. 2015:134():61-71. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2015.05.002. Epub 2015 Jun 12

[PubMed PMID: 26310149]

[32]

Wilson SE. Corneal wound healing. Experimental eye research. 2020 Aug:197():108089. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2020.108089. Epub 2020 Jun 15

[PubMed PMID: 32553485]

[33]

Liu J, Li Z. Resident Innate Immune Cells in the Cornea. Frontiers in immunology. 2021:12():620284. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.620284. Epub 2021 Feb 26

[PubMed PMID: 33717118]

[34]

Ljubimov AV, Saghizadeh M. Progress in corneal wound healing. Progress in retinal and eye research. 2015 Nov:49():17-45. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2015.07.002. Epub 2015 Jul 18

[PubMed PMID: 26197361]

[35]

Thoft RA, Friend J. The X, Y, Z hypothesis of corneal epithelial maintenance. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 1983 Oct:24(10):1442-3

[PubMed PMID: 6618809]

[36]

Liu J, Xiao C, Wang H, Xue Y, Dong D, Lin C, Song F, Fu T, Wang Z, Chen J, Pan H, Li Y, Cai D, Li Z. Local Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells Promote Corneal Regeneration after Epithelial Abrasion. The American journal of pathology. 2017 Jun:187(6):1313-1326. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.02.010. Epub 2017 Apr 15

[PubMed PMID: 28419818]

[37]

Yang L, Di G, Qi X, Qu M, Wang Y, Duan H, Danielson P, Xie L, Zhou Q. Substance P promotes diabetic corneal epithelial wound healing through molecular mechanisms mediated via the neurokinin-1 receptor. Diabetes. 2014 Dec:63(12):4262-74. doi: 10.2337/db14-0163. Epub 2014 Jul 9

[PubMed PMID: 25008176]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[38]

Loureiro RR, Gomes JÁP. Biological modulation of corneal epithelial wound healing. Arquivos brasileiros de oftalmologia. 2019 Jan-Feb:82(1):78-84. doi: 10.5935/0004-2749.20190016. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30652772]

[39]

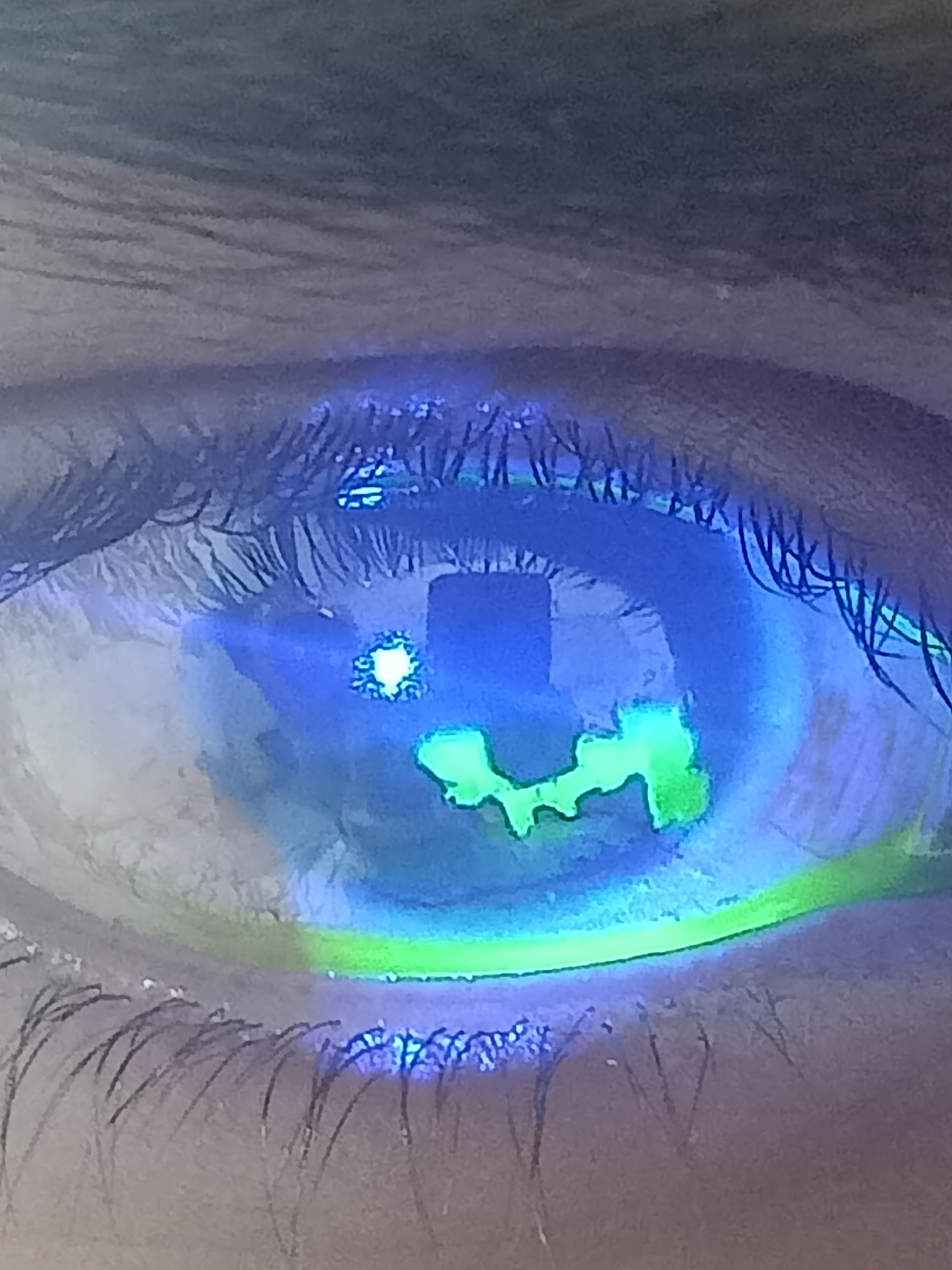

Hakimi AA, Carter S, Garg S. Detecting corneal injury with a selfie. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2022 Nov:29(11):1403-1404. doi: 10.1111/acem.14577. Epub 2022 Aug 17

[PubMed PMID: 35921203]

[40]

Tripathy K. Documentation of corneal epithelial defects with a fluorescein angiographic imaging system. Clinical case reports. 2019 Sep:7(9):1815-1816. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.2350. Epub 2019 Jul 30

[PubMed PMID: 31534763]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[41]

Wilson G, Ren H, Laurent J. Corneal epithelial fluorescein staining. Journal of the American Optometric Association. 1995 Jul:66(7):435-41

[PubMed PMID: 7560732]

[43]

Jamali A, Hu K, Sendra VG, Blanco T, Lopez MJ, Ortiz G, Qazi Y, Zheng L, Turhan A, Harris DL, Hamrah P. Characterization of Resident Corneal Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells and Their Pivotal Role in Herpes Simplex Keratitis. Cell reports. 2020 Sep 1:32(9):108099. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108099. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 32877681]

[44]

Bhargava M, Bhambhani V, Paul RS. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography characteristics and management of a unique spectrum of foreign bodies in the cornea and anterior chamber. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2022 Dec:70(12):4284-4292. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_878_22. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 36453330]

[45]

Kaiser PK. A comparison of pressure patching versus no patching for corneal abrasions due to trauma or foreign body removal. Corneal Abrasion Patching Study Group. Ophthalmology. 1995 Dec:102(12):1936-42

[PubMed PMID: 9098299]

[46]

Benson WH, Snyder IS, Granus V, Odom JV, Macsai MS. Tetanus prophylaxis following ocular injuries. The Journal of emergency medicine. 1993 Nov-Dec:11(6):677-83

[PubMed PMID: 8157904]

[48]

Dang DH, Riaz KM, Karamichos D. Treatment of Non-Infectious Corneal Injury: Review of Diagnostic Agents, Therapeutic Medications, and Future Targets. Drugs. 2022 Feb:82(2):145-167. doi: 10.1007/s40265-021-01660-5. Epub 2022 Jan 13

[PubMed PMID: 35025078]

[49]

Clemons CS, Cohen EJ, Arentsen JJ, Donnenfeld ED, Laibson PR. Pseudomonas ulcers following patching of corneal abrasions associated with contact lens wear. The CLAO journal : official publication of the Contact Lens Association of Ophthalmologists, Inc. 1987 May-Jun:13(3):161-4

[PubMed PMID: 3329585]

[50]

Calder LA, Balasubramanian S, Fergusson D. Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for corneal abrasions: meta-analysis of randomized trials. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2005 May:12(5):467-73

[PubMed PMID: 15860701]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[51]

Wakai A, Lawrenson JG, Lawrenson AL, Wang Y, Brown MD, Quirke M, Ghandour O, McCormick R, Walsh CD, Amayem A, Lang E, Harrison N. Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for analgesia in traumatic corneal abrasions. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017 May 18:5(5):CD009781. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009781.pub2. Epub 2017 May 18

[PubMed PMID: 28516471]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[52]

Al-Saleh GS, Alfawaz AM. Management of traumatic corneal abrasion by a sample of practicing ophthalmologists in Saudi Arabia. Saudi journal of ophthalmology : official journal of the Saudi Ophthalmological Society. 2018 Apr-Jun:32(2):105-109. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2017.10.007. Epub 2017 Oct 31

[PubMed PMID: 29942177]

[53]

Ball IM, Seabrook J, Desai N, Allen L, Anderson S. Dilute proparacaine for the management of acute corneal injuries in the emergency department. CJEM. 2010 Sep:12(5):389-96

[PubMed PMID: 20880433]

[54]

Saccomano SJ, Ferrara LR. Managing corneal abrasions in primary care. The Nurse practitioner. 2014 Sep 18:39(9):1-6. doi: 10.1097/01.NPR.0000452977.99676.cf. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25140844]

[55]

Jolly R, Arjunan M, Theodorou M, Dahlmann-Noor AH. Eye injuries in children - incidence and outcomes: An observational study at a dedicated children's eye casualty. European journal of ophthalmology. 2019 Sep:29(5):499-503. doi: 10.1177/1120672118803512. Epub 2018 Oct 1

[PubMed PMID: 30270661]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[56]

Tsai CC, Kau HC, Kao SC, Liu JH. A review of ocular emergencies in a Taiwanese medical center. Zhonghua yi xue za zhi = Chinese medical journal; Free China ed. 1998 Jul:61(7):414-20

[PubMed PMID: 9699394]