Continuing Education Activity

Hypothermia occurs when the body dissipates more heat than it absorbs or creates, resulting in failure to maintain homeostasis and proper bodily function. While hypothermia's usual causes are excessive cold stress and inadequate thermogenesis, external factors can increase the risk of developing hypothermia. The condition is potentially fatal if not promptly treated. Familiarity with its myriad presentations and management strategies is crucial to medical practice.

This activity for healthcare professionals enhances the learner's competence in evaluating and treating patients with hypothermia. This activity equips clinicians to contribute meaningfully to the multidisciplinary care of patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Identify possible hypothermia causes and describe the bodily changes associated with this condition.

Describe the common presentations of a patient with accidental hypothermia.

Determine the appropriate management approach for patients presenting with hypothermia.

Develop effective collaboration and communication strategies within the interprofessional team to enhance outcomes for patients presenting with hypothermia.

Introduction

Hypothermia is defined as a drop in body temperature below 35 °C. The condition is common in cold geographic areas and during cooler months, though it can also develop in locations with milder climates.[1] Hypothermia affects all organ systems. Presenting symptoms depend on the severity of the condition.

The hypothalamus regulates body temperature through autonomic mechanisms. This region of the brain receives input from central and peripheral thermal receptors. Muscle tone and basal metabolic rate (BMR) increase initially in response to cold stress. Heat production can double through these mechanisms. Shivering also enhances heat production, increasing metabolism 2 to 5 times the baseline BMR.[2]

Newborns lack the shivering mechanism due to incomplete development of the nervous system. However, brown fat helps generate heat in newborns' bodies. Brown fat's thermogenin increases mitochondrial membrane permeability and disrupts the electron transport chain (ETC) enzymes. ETC disruption and subsequent hydrogen ion leakage block ATP production and generate body heat.

Thyroid, catecholamine, and adrenal hormones also increase in response to cold stress. Cold-induced, sympathetically mediated peripheral vasoconstriction reduces heat loss. Behavioral changes like adding more clothing, seeking shelter, starting a fire, and exercising help retain or produce body heat.

Patients with mild hypothermia have a core body temperature ranging from 32 to 35 °C (90-95 °F). The core temperature for moderate hypothermia is 28 to 32 °C (82-90°F). The core body temperature is less than 28 °C (82 °F) for severe or profound hypothermia. Durrer et al use a hypothermia staging scheme for rescue work (see under "Staging" below) to determine which patients can benefit from resuscitation.[3] Worsening degrees of hypothermia result in great morbidity and mortality.[4][5]

Etiology

Hypothermia occurs when the body releases more heat than it absorbs or generates. Vital factors that help retain heat in the body include central and peripheral nervous system regulation and behavioral adaptation.[6][7]

Extremes of age, hypoglycemia, malnutrition, and various endocrine disorders are common reasons for inadequate heat production. Conditions resulting in heat loss include inflammatory skin disorders like psoriasis and burns and excessive peripheral vasodilation from nervous system injuries. Cerebrovascular accidents, neurodegenerative disorders, and drug abuse may disrupt the hypothalamic thermoregulation function. Hypothermia may also be iatrogenic, often from drugs like general anesthetics, beta-blockers, meperidine, clonidine, neuroleptics, and alcohol.

Besides organic causes, impaired behavioral response to cold stress may result in hypothermia, as happens in individuals with mental health conditions like dementia and drug abuse disorder. Situational circumstances from lack of shelter or clothing may occur in people experiencing homelessness.[8][9]

Epidemiology

About 700 to 1500 hypothermia-related fatalities are reported in the United States each year. The condition most frequently affects adults between the ages of 30 and 49, with occurrence 10 times greater in men than women. However, hypothermia's true incidence is unknown. Even with optimized in-hospital care, the mortality of moderate to severe hypothermia still approaches 50%.

Pathophysiology

The body's core temperature arises from the balance between heat produced by the body and heat lost to the surroundings. The normal value ranges from 36.5 to 37.5 °C. Four mechanisms are responsible for heat loss: radiation, conduction, convection, and evaporation.

Heat radiation occurs when the body emits electromagnetic energy to the surroundings. Heat conduction is when thermal energy transfers between objects in contact. Heat loss by convection entails air molecules moving past a heated object. Evaporation happens when heat transforms liquid into gas, as when the thermal energy from the skin vaporizes sweat.

While normal body heat loss is most often due to radiation, hypothermia is more likely to arise from cold air exposure (convection), cold water contact (conduction), and excessive sweating (evaporation).[10]

The body initially increases metabolism, ventilation, and cardiac output to maintain function when the ambient temperature drops. Heat loss can overwhelm the body and disrupt the shivering mechanism without external warming. Multiple organ systems, including neurologic, metabolic, and cardiac, will cease to function, ultimately leading to death.[11] Sinoatrial disturbances may result in atrial or ventricular fibrillation.

History and Physical

Hypothermia may result in cardiorespiratory arrest. A quick primary survey—assessing the airway, breathing, circulation, disability, and exposure (ABCDE)—should reveal the need for immediate resuscitation. Patients presenting with unconsciousness, pulselessness, and apnea must be given resuscitative care immediately, regardless of the cause. Once stabilized or if emergency conditions have been ruled out, a more detailed investigation may be started.

People who have suffered hypothermia typically have a history of recent significant cold exposure. The presenting symptoms depend on the core body temperature, which must be obtained accurately to diagnose and manage the condition effectively. When used correctly, epitympanic thermometers reflect the carotid artery temperature and can be reasonably reliable.

Rectal and bladder temperature measurements are reasonable in conscious individuals with mild to moderate hypothermia. However, these approaches may not be appropriate for critical patients during rewarming, as they lag behind true core temperature. In the prehospital setting, rectal and bladder temperature monitoring may further expose the patient and worsen hypothermia. Esophageal temperature measurement is most accurate when the probe is in the esophageal lower third but should only be performed in patients with an advanced airway in place.

Oral temperature is only useful in ruling out hypothermia, as most commercially available thermometers cannot read under 35 °C. Tympanic thermometers are also unreliable.

The core body temperature must be obtained immediately, as it is critical in determining the appropriate management. This parameter correlates significantly with the symptoms of each stage of hypothermia, though it can be challenging to obtain in the prehospital setting.[12]

In mild hypothermia, the core body temperature ranges from 32 to 35 °C (90-95 °F). The symptoms are often subtle and nonspecific, including hunger, nausea, fatigue, shivering, and pale-dry skin. Patients may also have increased muscle tone, blood pressure, heart rate, and respiration as the body attempts to promote thermogenesis. Shivering is usually present unless the patient's energy stores have been depleted, as in cases of malnutrition or underlying endocrinopathy. Potential neurologic symptoms include cognitive decline, memory and judgment impairment, ataxia, and dysarthria. "Cold diuresis" may occur due to peripheral vasoconstriction, leading to increased diuresis and subsequent volume depletion.

Patients with moderate hypothermia have a core body temperature of 28 to 32 °C (82-90 °F). Cognitive decline and lethargy are common. CNS depression may lead to hyporeflexia, with the pupils being less responsive and dilated. Hypotension, bradycardia, and bradypnea may ensue. Shivering typically ceases when the core temperature reaches 30 to 32 °C, at which point, paradoxical undressing may be observed. Susceptibility to dysrhythmias increases, with atrial fibrillation being the most common.

Individuals with severe hypothermia have a core body temperature of less than 28 °C (82 °F). Cerebral blood flow continues to decline until patients become unresponsive. Blood pressure, heart rate, and cardiac output also continue to decrease. Atrial and junctional dysrhythmias may be present. Pulmonary congestion, oliguria, and areflexia may occur. The condition may result in cardiorespiratory failure.[13]

All patients with suspected hypothermia should have a complete history and physical examination to exclude local cold-induced injuries. A history of trauma or an underlying condition must be ruled out. Vital signs and symptoms inconsistent with the degree of hypothermia may be clues to an alternate diagnosis, such as hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, sepsis, hypoglycemia, carbon monoxide poisoning, alcohol abuse, malnutrition, and unintentional or intentional overdose.

Hypothermia may arise from overdosing on some medications, such as beta-blockers, clonidine, neuroleptics, meperidine, and general anesthetic agents. Beta-blockers may blunt the effects of the catecholamine surge. Ethanol, sedative-hypnotics, and phenothiazines also reduce the body's ability to respond to low ambient temperatures.

Evaluation

Again, for all potentially unstable patients, the trauma ABCs should be the clinician's initial focus of evaluation. Remove all clothing after finishing the primary survey and place dry, warm blankets on the patients' fully exposed chest. Standard laboratory evaluation should include finger-stick glucose, complete blood count, and a basic metabolic panel.

A rise in hemoglobin and hematocrit may be due to cold diuresis from impaired antidiuretic hormone secretion. Glucose levels do not follow a specific pattern unless hypo- or hyperglycemia is triggered in patients with diabetes mellitus. Electrolyte reassessment every 4 hours is recommended when resuscitating patients with hypothermia.

A coagulation panel must be obtained when invasive procedures are deemed necessary. However, this test generally requires the patient's in vivo temperature to be 37 °C to be reliable. Fibrinogen should also be checked to rule out disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Serum lactate, creatinine kinase, troponin, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), cortisol, toxicology screen, fibrinogen, lipase, and magnesium may be obtained to find non-environmental causes of hypothermia.

Imaging should be dictated by clinical need, as some patients may have had an inciting incident like trauma or cerebrovascular accident that led to a significant body temperature drop. Chest x-ray may be normal in the absence of trauma or an underlying thoracic condition. Bedside ultrasound may be used to confirm cardiac activity and volume status. Head computed tomography (CT) may benefit individuals with altered mental status not proportional to the severity of hypothermia, especially if trauma or stroke is suspected.[13]

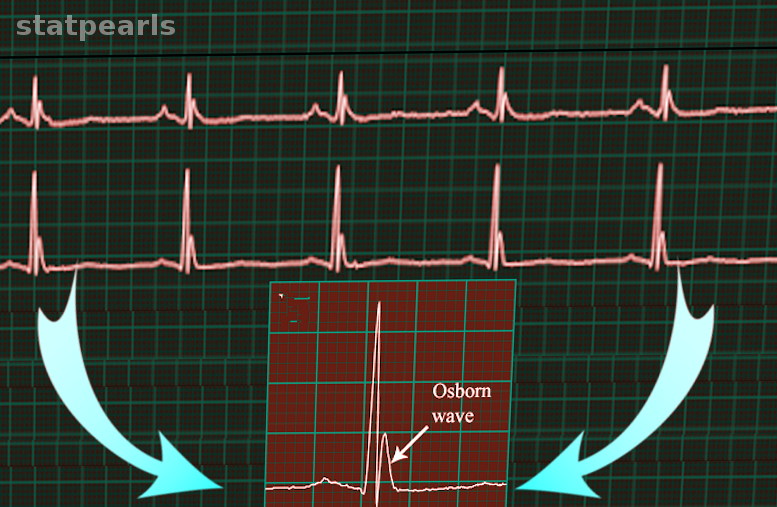

Electrocardiography (ECG) must be obtained due to the frequency of dysrhythmias in patients with hypothermia. Cold temperatures can slow down impulse conduction through potassium channels, prolonging QT intervals. An elevated J point that can produce an Osborn or J wave may also be observed (see Image. Osborn wave). This wave most commonly appears in the precordial leads, and its height is proportional to the degree of hypothermia.

Any dysrhythmic pattern is possible, but atrial fibrillation is the most common. Bradycardia is more common in patients with moderate to severe hypothermia and increases the risk of ventricular arrhythmia.

Treatment / Management

Hypothermia management focuses on quick rewarming and preventing further heat loss, ensuring that the airway, breathing, and circulation are adequately and promptly addressed. Wet clothing should be immediately removed and replaced with dry clothing or insulation.[14][15] Once emergencies have been ruled out, a more detailed examination must be made, noting the complete history, mental status, physical exam, and core temperature.

Patients presenting with symptoms of moderate or severe hypothermia must be moved gently, as movements may increase cardiac irritability and precipitate fatal arrhythmia.[16] Comorbid medical conditions and trauma must also be investigated and addressed.[17] Individuals who have documented hypoglycemia may be supplied oral glucose.

Rewarming of hypothermic patients involves passive external rewarming, active external rewarming, active internal rewarming, or a combination of these techniques. The treatment of choice for mild hypothermia is passive external rewarming at a rate of 0.5 to 2 °C per hour. After removing wet clothing, additional insulating layers are placed on the patient's body to prevent heat loss and promote heat retention.

Shivering allows the body to produce up to a 5-fold heat increase from baseline spontaneously. However, this method requires adequate glucose stores. Additionally, vigorous shivering can be problematic in people with limited cardiopulmonary reserves as it increases oxygen consumption.

Active external rewarming is necessary for moderate to severe hypothermia and mild hypothermia refractory to standard measures. A heated air unit can decrease heat loss and transfer heat through convection. Placing a heated pack on the patient's body can also help facilitate rewarming. Heat must be applied to the axillae, chest, and back for efficiency.[18]

Water immersion is an alternative but more cumbersome and challenging to monitor. Immersing the extremities in warm water (44-45 °C) requires great care and attention. Rapid rewarming can cause peripheral vasodilation, forcing cold venous blood to return to circulation and increase cardiac load abruptly.

Some patients may require more invasive methods besides active external rewarming. Methods range from airway rewarming with humidified air to full cardiopulmonary bypass. Humidified air and warm intravenous fluids at 40 to 42 °C can be used safely. Warm saline lavage of various body cavities such as the stomach, bladder, colon, peritoneal, and pleura may also be considered. Pleural and peritoneal lavages are preferable due to the larger mucosal surface areas.

Pleural lavage involves placing 2 thoracostomy tubes. The first is positioned between the 2nd and 3rd anterior intercostal space in the midclavicular line. The other thoracostomy tube is placed between the 5th and 6th intercostal space at the posterior axillary line. The warm fluid infusion should begin through the anterior tube and drain through the posterior tube. Meanwhile, peritoneal lavage entails placing 2 or more catheters in the peritoneal cavity. This approach is both therapeutic and diagnostic, as it allows for the detection of occult abdominal trauma while rewarming the peritoneal cavity.

Extracorporeal rewarming techniques allow for even faster rewarming. The methods include hemodialysis, continuous arteriovenous rewarming, cardiopulmonary bypass, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) if available. Hemodialysis is the most accessible and can raise the core temperature by 2 to 3 °C per hour.

Arteriovenous (AV) rewarming entails warming femoral arterial blood and allowing it to flow to the contralateral femoral vein. This method raises the temperature by 4.5 °C per hour. Both hemodialysis and AV rewarming require the patient to have adequate blood pressure.

Cardiopulmonary bypass surgery and venoarterial ECMO are the most effective but highly invasive rewarming methods. These procedures are reserved for patients in cardiac arrest, hemodynamically unstable individuals, and people unresponsive to less invasive rewarming techniques. Cardiopulmonary bypass and ECMO can raise the core temperature by 7 to 10 °C per hour and simultaneously improve oxygenation and circulatory support. However, not all facilities can offer these procedures. Cardiopulmonary bypass and ECMO also require systemic anticoagulation, predisposing patients to spontaneous bleeding.

Differential Diagnosis

An abnormally low body temperature is associated with various medical conditions. The differential diagnosis of hypothermia may be classified into the following:[19]

- Central failure

- Cerebrovascular accident

- CNS trauma

- Hypothalamic dysfunction

- Metabolic failure

- Toxins

- Pharmacologic effects

- Peripheral failure

- Acute spinal cord transection

- Neuropathy

- Endocrinologic failure

- Alcoholic or diabetic ketoacidosis

- Hypoadrenalism

- Hypopituitarism

- Lactic acidosis

- Insufficient energy

- Hypoglycemia

- Malnutrition

- Neuromuscular compromise

- Extreme ages with inactivity

- Impaired shivering

- Dermatologic

- Burns

- Medication and toxins

- Iatrogenic cause

- Emergency childbirth

- Cold infusion

- Heat-stroke treatment

- Miscellaneous

- Carcinomatosis

- Cardiopulmonary disease

- Major infection

- Multisystem trauma

- Shock

A thorough evaluation is necessary in determining hypothermia's underlying cause and treatment planning.

Staging

The following table summarizes the staging used by Durrer et al for practical rescue work:

| Hypothermia Stage |

Symptoms |

Core Temperature in °C |

| I |

Clear consciousness with shivering |

35 - 32 |

| II |

Impaired consciousness without shivering |

32 - 28 |

| III |

Unconsciousness |

28 - 24 |

| IV |

Apparent death |

24 - 13.7 |

| V |

Death due to irreversible hypothermia |

<13.7 |

A serious underlying injury must be suspected if the core temperature drops rapidly.[3]

Prognosis

Severe hypothermia can be lethal, though many factors may improve the prognosis. For example, hemodynamically stable patients with primary hypothermia have a survival rate of approximately 100% with full neurological recovery if treated promptly with active external or minimally invasive rewarming techniques. Meanwhile, patients in cardiac arrest treated by ECMO have a survival rate approaching 50%. The absence of hypoxia, trauma, or a serious underlying disease may improve the outcomes for these patients. Full neurological recovery has been reported in accidental hypothermia reaching 14 °C.[19]

Ventricular fibrillation in patients with hypothermia has a favorable neurological outcome if resuscitative efforts quickly revive the patient. In contrast, hypothermia-related asystole is generally refractory to normal advanced cardiac life support (ACLS). Patients in asystole may need rewarming to 35 °C before cardiac rhythm is restored. Blood potassium may be determined in patients with refractory asystole. A level greater than 12 mEq/L indicates irreversible tissue death and cell lysis.

Individuals who are resuscitated quickly usually have good outcomes, though they may have residual frostbite and muscle injury. Extremes of age and severe hypothermia generally have a poorer prognosis.

Complications

Frostbite is a complication of hypothermia that may potentially lead to limb loss if not treated in a timely fashion. This lesion is a form of dry gangrene. A secondary infection can turn it into wet gangrene. Infection by the anaerobic species Clostridium perfringens produces gas, manifesting as crepitus in the skin. Frostbite infection may lead to amputation if refractory to medical treatment.

Other complications of hypothermia include the following:[11]

- Cold diuresis

- Rhabdomyolysis

- Aspiration

- Hyperkalemia

- Frostbite

- Acute kidney injury

- Pulmonary edema

- Ataxia

- Ventricular and atrial arrhythmias, frequently atrial or ventricular fibrillation and pulseless electrical activity

- Coma

- Pancreatitis

- Death

Rewarming also produces complications, which include the following:[20][21][22][23][24]

- Takotsubo cardiomyopathy

- Systemic inflammation

- Electrical abnormalities like hyperkalemia, hypophosphatemia, hypomagnesemia, and hypocalcemia

- Rhabdomyolysis

- Ventricular and atrial arrhythmias (A. fibrillation, ventricular arrhythmia, PEA)

- Infection like pneumonia

- Platelet dysfunction from thrombocytopenia to platelet aggregation and thrombosis.

- Alterations in glucose homeostasis from reduced glucose utilization to insulin resistance

Prompt recognition and appropriate treatment help reduce the likelihood of complications.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Hypothermia is avoidable, and clinicians can teach patients measures that can help prevent this condition. The first is behavioral modification. Individuals should stay indoors as much as possible in cold weather. Otherwise, proper clothing should be worn for protection outdoors.

The second is protecting vulnerable household members. Caregivers of young children, older individuals, and people with mental health issues must be reminded to ensure that their charges wear proper clothing. Medications that can cause hypothermia at large doses must be kept out of reach.

The third is ensuring that dwellings are adequately warmed, with fire safety measures installed. The fourth is avoidance of activities that increase the risk of hypothermia, such as snowboarding or mountaineering in cold places.

Pearls and Other Issues

The most important points to remember about hypothermia management are the following:

- Hypothermia arises from inadequate heat retention or massive heat loss due to various causes. Symptoms range from mild to severe. Severe hypothermia may result in death if not treated promptly.

- Patients with hypothermia may present with unconsciousness, pulselessness, and lack of respiration. Resuscitation must be initiated right away in such individuals.

- Most commercial thermometers can only read to a minimum of 34 °C, making a special low-reading thermometer necessary during patient examination.

- The esophageal thermometer is the most accurate way of determining a patient’s temperature.

- Rectal temperatures take up to 1 hour to adjust to core temperature changes.

- Patients with hyperkalemia may not show the typical ECG changes associated with elevated potassium levels.

- Coagulation tests may be inaccurate unless the patient has been warmed to 37 °C.

- ECG may show J waves in patients with hypothermia.

- Cardiopulmonary bypass and ECMO are the most invasive but effective ways to rewarm a hemodynamically unstable patient.

- If the patient fails to rewarm despite appropriate rewarming techniques, underlying causes like hypoglycemia, infection, hypothyroidism, and adrenal insufficiency must be investigated.

Importantly, hypothermia is avoidable. Patient education on preventive measures is crucial, especially when caring for vulnerable individuals.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Hypothermia is potentially lethal if not quickly recognized and treated. Managing the condition requires a multidisciplinary team. Emergency medical services (EMS) provide the patient with initial treatment in the prehospital setting. EMS personnel are often the first healthcare professionals that patients with hypothermia encounter.

Afterward, patients are taken to the emergency department, where the emergency medicine physicians and nurses further stabilize patients. A highly trained emergency unit best accomplishes resuscitation and quick rewarming. After stabilization, emergency medicine physicians also investigate associated injuries and send referrals to specialists when appropriate.

Hypothermic patients are prone to many complications, often requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission. Nurses provide continuous monitoring at the ICU, administer medications and fluids, and coordinate care. A pulmonologist and cardiologist may co-manage respiratory and cardiovascular complications, respectively. Nephrologists' services may be required if hemodialysis is warranted. Surgeons may be needed to debrid severe frostbites. Cardiothoracic specialists may perform cardiopulmonary bypass or ECMO if necessary.[13] Respiratory therapists assist in treating breathing problems if present. Pharmacists dispense prescription medications.

After discharge, the primary care doctor oversees the patients' general health needs and monitors for complications. Physical and occupational therapists help in patient rehabilitation. Seamless coordination between these healthcare providers ensures the best outcomes for patients who have had hypothermia.