Continuing Education Activity

First-degree burns are superficial burns involving the epidermal layer of skin. The skin is the largest organ of the human body, with its weight comprising up 16% of total body weight. The layers of skin consist of the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis. This activity reviews the cause, pathophysiology, and presentation of first degree burns and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

- Review the causes of first degree burns.

- Describe the presentation of first degree burn.

- Summarize the treatment of first degree burn.

- Explain the importance of improving care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by first degree burn.

Introduction

First-degree burns are superficial burns involving the epidermal layer of skin. The skin is the largest organ of the human body, with its weight comprising up 16% of total body weight. The layers of skin consist of the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis. The functions of skin include providing a protective barrier, regulating temperature, controlling evaporation, excretion, and sensing heat, cold, pressure, and touch.

Embryological Origin

The epidermis arises from surface ectoderm with specialized cells such as antigen-processing Langerhans cells of bone marrow origin, and melanocytes and pressure-sensing Merkel cells from neural crest origin. Blood supply is from diffusion through the dermoepidermal junction. The histology of the epidermis is of a stratified, squamous epithelium that is composed of keratinocytes. The epidermis can further be stratified by layers which are: stratum germinativum, stratum spinosum, stratum granulosum, and stratum corneum.[1][2][3]

Etiology

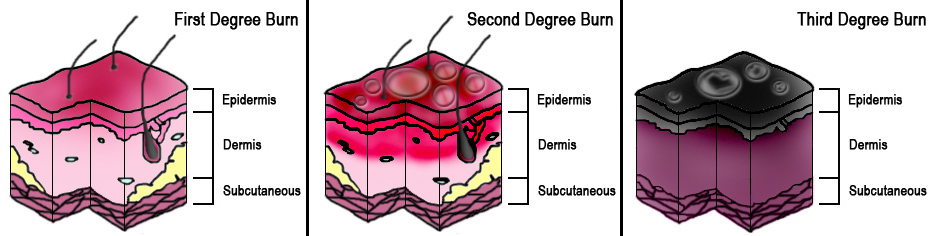

Burns can be classified by mechanism of injury, depth of burn in relation to layers of the skin, and severity of the burn. Common injuries are thermal, electrical, chemical, radiation, and nonaccidental.[4][5]

Classification Based on Mechanism

Thermal burns are most commonly due to fire, hot liquids, or contact with a hot surface. Scalding injuries are caused by exposure to hot water in baths or showers, hot drinks, oil, or steam. These types of injuries are most common in children younger than age 5 and elderly patients. These burns present as first or second-degree burns; however, third-degree burns may also result from prolonged exposure.

Electrical burns are classified as high voltage, low voltage, or as flash burns secondary to an electric arc. Electrical burns are commonly seen in children playing with electrical cords or outlets. In adults, these injuries are seen in inexperienced people working with electrical wiring and electricians working on high voltage power lines. One can see the entry and exit point where the current passes through the body. Severe injuries associated with these burns include cardiac arrhythmia and myoglobinuria. These occur due to damage to tissue between entry and exit points.

An acid or alkali can cause chemical burns. Skin contact or oral mucosa ingestion cause an irritant effect that leads to chemical burn injury. Common household products that cause chemical burns include drain cleaners, paint thinner, and lye. Alkali burns tend to be more severe, as they lead to a liquefactive necrosis process. Acids, on the other hand, cause coagulative necrosis.

Radiation injuries are due to extended exposure to ultraviolet light, for example, sunlight or tanning booth exposure, or from ionizing radiation such as radiation therapy or x-rays. First-degree burns are most commonly due to radiation from sun exposure. Increased levels of melanin can add a protective effect decreasing the chances of sunburn. Sunburn has four stages: golden or tan, red, purplish-red, and blister red. When tanning occurs, it is due to an increase in melanin pigmentation, after which it reddens and becomes more sensitive to touch. Further exposure causes edema, leading to purplish discoloration. The final stage involves blister formation and skin peeling.

Non-accidental burn injuries can be caused by assault or negligence, commonly due to thermal injury. Suspect this in children, when burns are symmetrical and involve the feet up to legs and the perineum. Multiple burns are common.

Classification of Burns by Depth or Degree

This classification is based on the American Burn Association severity classification system.

- Superficial (first degree): epidermis (example sunburn)

- Superficial partial-thickness (second degree): extends into superficial dermis

- Deep partial-thickness (second degree): extends into the superficial dermis

- Full-thickness (third degree): extends through the entire dermis

- Fourth degree: extends through the entire skin, into underlying fat, muscle, and bone.

Epidemiology

From 2009 through 2015, the trend of indoor tanning use among youth in the United States decreased. However, there is still a report of one or more burns among three-quarters of the study population.[6][7]

Pathophysiology

Protein cellular denaturation with the loss of collagen cross-linking starts to occur with an increased temperature above 44 C. This causes necrosis secondary to abnormal osmotic and hydrostatic pressure gradients, with the movement of fluid into interstitial spaces. There are three zones of injury: coagulation, stasis, and hyperemia.

- The Zone of Coagulation is irreversible tissue loss due to coagulation and the point of maximal damage

- The Zone of Stasis is the potentially salvageable zone around the zone of stasis due to decreased tissue perfusion.

- The Zone of Hyperemia has increased perfusion most likely to recover.

History and Physical

The clinical history for burns involves asking about demographics, including age, gender, social history, and family, birth, and development history in children. Elucidating the mechanism, onset, and associated pain symptoms is vital. First-degree burns present with increased sensitivity to touch, associated erythema, and skin-stripping depending on the timeline of the initial incident. The examination should assess the total burn surface area, which can be calculated by the rule of nines.

Evaluation

Based on severity, initial evaluation for burns follows advanced trauma life support (ATLS) protocol. One should perform primary and secondary surveys.[8][9]

- In the primary survey, assess the ABCs: (airway, breathing circulation, disability, and exposure);

- Maintain the airway with cervical spine protection: ensure a patent airway;

- Breathing and ventilation: Is the patient breathing? Evaluate for injuries that can severely impair ventilation such as tension pneumothorax;

- Circulation and hemorrhage control: Is there a palpable pulse? Assess the level of consciousness, skin color, and other signs of perfusion. Identify the source of bleeding, if present, and control the bleeding;

- Disability (neurologic evaluation): Are there associated disabilities? This assessment should also include a quick neurologic evaluation to establish a level of consciousness, pupillary size and reaction, lateralizing signs, and level of spinal cord injury (if present);

- Exposure with environmental control: Is the patient completely examined for a thorough assessment? Cover the patient to avoid hypothermia;

- Secondary evaluation of burns should assess for extent, depth, and circumferential wounds;

- In first degree burns, patients present without associated airway symptoms, and a thorough history and detailed examination should be performed; and

- Estimate and record the size and depth of the burn.

Treatment / Management

Management can be divided into categories based on burn classification of minor, moderate, or major burns. First-degree burns tend to be minor in severity and can be managed in the outpatient setting. Management goals include pain relief with oral analgesics and topical agents (e.g., Silvadene, 3% Bismuth Tribromophenate, or petroleum gauze). The area should be cleaned to remove the superficial skin layer which is stripping. Non-adhesive dressings can be used, especially in children when flexure regions are involved. These should be changed three times per week in the absence of infection. If infection occurs, daily wound examination and dressing change are required. A seven-day course of flucloxacillin is first-line therapy. Another option is erythromycin. Clarithromycin should be used if the patient is intolerant of erythromycin. Manage for moderate burns in the hospital setting. Severe burns warrant treatment in a burn center.[10][11]

Pearls and Other Issues

Avoid hypothermia in children since children have higher body surface area, therefore lose heat more rapidly

In children, non-accidental trauma should be considered especially when it involves the back of hands or feet, buttocks, perineum, or legs

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

First-degree burns may not be considered serious, but their morbidity depends on the location and extent of the burn. In children and the elderly, an extensive first-degree burn can lead to very high morbidity from the pain and hypothermia. In addition, if the burn involves the face or genital area, it may lead to loss of function. The key to first-degree burn management is patient education. Nurses in the workforce should educate workers about safety precautions when working with hazardous chemicals. Employers are mandated to provide workers with safety education and adequate protective equipment. The nurse should also educate the parents on the safe storage of chemicals in the home, away from the reach of children. Finally, the nurse should provide basic education on how to manage the pain of a first-degree burn and the importance of preventing any further trauma to the burned site.[12][13] (Level V)

Outcomes

The prognosis for the majority of people with a first-degree burn is excellent. However, children and the elderly may require admission depending on the degree and location of the burn. Besides pain, hypothermia is a potential complication. Once the pain has subsided, first degree burns rarely have any adverse sequelae.