Continuing Education Activity

Erythema multiforme (EM) is a cutaneous and mucosal hypersensitivity reaction with characteristic lesions triggered by certain antigenic stimuli. It represents an acute, sometimes recurrent condition of the skin and mucosal membranes manifested by papular, bullous, and necrotic lesions. Its causes are variable and numerous, and its evolution is generally favorable. This activity reviews the cause, pathophysiology, and presentation of erythema multiforme and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

- Review the causes of erythema multiforme.

- Describe the presentation of erythema multiforme.

- Summarize the treatment options for erythema multiforme.

- Outline the importance of improving care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by erythema multiforme.

Introduction

Erythema multiforme (EM) is a cutaneous and mucosal hypersensitivity reaction with characteristic lesions triggered by certain antigenic stimuli. It represents an acute, sometimes recurrent condition of the skin and mucosal membranes manifested by papular, bullous, and necrotic lesions. Its causes are variable and numerous, and its evolution is generally favorable.[1][2][3][4]

Most lesions appear in 48 to 72 hours and favor the extremities. The lesions remain localized to one site and heal within 7 to 21 days. Common precipitating factors include herpes simplex virus, histoplasmosis, and Epstein Barr virus. Recurrences are not uncommon if the trigger is Herpes simplex. While most cases are mild, severe cases can be life-threatening. The mucous membranes are involved in 2 to 10% of individuals. Overall, the majority of cases of EM are linked to medications.

Etiology

The etiology of EM is most commonly Herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 and 2 infections and Mycoplasma pneumoniae, but many other viral, fungal, and bacterial infections have been implicated. More rarely, and in a more questionable way, vaccines have been incriminated.[5][6][7]

Drugs associated with EM include antibiotics like penicillins, cephalosporins, macrolides, sulfonamides, anti-tuberculosis agents, antipyretics, and many others. In some patients, contact with heavy metals, herbal agents, topical therapies, and poison ivy can trigger EM.

Epidemiology

EM is reported worldwide without any ethnic predilection. It occurs at any age, more frequently in young adults. The average age is between 20 and 30 years, and 20% of cases occur in children. It is more common in men with a sex ratio of 1 in 5. Prevalence is not known but appears to be well below 1%. As the classification is not always clear, cases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) have frequently been included in studies on EM.

Patients with HIV, on corticosteroids, immunosuppressed, having undergone a bone marrow transplant, and lupus are predisposed to developing EM.

Pathophysiology

EM is often associated with viral or bacterial infections, especially HSV. Studies have demonstrated the presence of HSV-DNA by a polymerase chain reaction in acute or sequellae EM lesions. The predisposing factors are unknown. HLA-DQ3 is reported to be associated with postherpetic EM and has been suggested as an additional diagnostic marker. Other human leukocyte antigen groups have also been reported as markers of recurrent EM.

The damage to the epithelial cells is via cell-mediated immunity. During the early phase of the disease, there is an influx of macrophages and CD8 T lymphocytes, which release a wide range of cytokines that mediate the inflammation and resultant cell death.

When the process is due to drug hypersensitivity, the earliest pathological feature is necrosis of keratinocytes.

Histopathology

A punch biopsy can be used to confirm the diagnosis of EM. The classic lesion will reveal a vacuolar interface dermatitis with marked infiltration with lymphocytes along the dermo-epidermal junction. In addition, one may see dyskeratosis of basal keratinocytes and hydropic changes. With advanced lesions, there is usually epidermal necrosis, subepidermal blisters, and vesiculation. There is a predominance of CD 8 T lymphocytes and macrophages.

History and Physical

A fever and a feeling of general unease may precede and/or accompany the eruption on the first days. Sometimes there is arthralgia or even joint swelling.

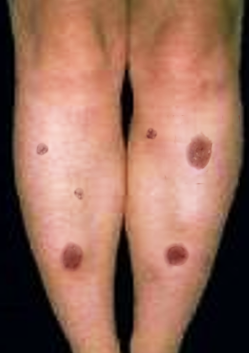

Clinically, the typical lesion of the EM is the target lesion, described as a rounded lesion that is regular with three concentric circles and a well-defined border. The peripheral ring is erythematous, sometimes microvesicular; the middle zone is often clearer, oedematous, and palpable, and the center is erythematous, covered by a blister. These different aspects evoke different stages of the evolving lesion.

The lesions measure less than 3 centimeters, and their location is mainly acral. They are symmetrical in the palms and backs of the hands, the feet, and the extended faces of the limbs. The trunk is often spared, but the face and ears can be reached. There is no pruritus but rather sensations of burning in some patients.

Mucosal lesions are common, mostly in the mouth, but also in the genital and ocular mucous membranes. They are initially bullous, then quickly turn into painful erosions. Thick hemorrhagic crusts may cover the labial lesions, and a fibrin-whitish coating may line the mucosal erosions of the cheeks, palate, and genitalia. These mucosal lesions occur most often at the same time as the skin lesions but can be shifted a few days before or after the eruption of targets. While skin lesions are nonpainful, mucosal lesions are frequently painful.

Pulmonary signs may also be present, such as a cough and dyspnea. They testify to a respiratory attack most often related to the inducing infection of the EM (mainly due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae).

When extensive skin involvement occurs, some patients may show signs of dehydration. Others with mucosal involvement may lose weight because of difficulty eating.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of EM is clinical. In case of doubt, a skin biopsy of the lesion center can be performed for histological study with immunofluorescence. It then shows epithelial intercellular edema with keratinocyte necrosis responsible for an intra- or sub-epidermal blister covered with a necrotic epidermis. A peri-vascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate is present in the superficial dermis without necrotic vascular lesions. Direct immunofluorescence is negative. The biological assessment provides no argument for the diagnosis of EM. However, it is useful to appreciate the severity of the disease. The chest x-ray may show interstitial radiological infiltrate (mainly in EM due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae). Renal, hepatic, or hematologic lesions have also been described and are not systematically sought after in mild forms.[8]

The etiological assessment must be adapted to the symptoms. In no case is an exhaustive report justified:

- Herpes infection, mainly with HSV-1, is most frequently the cause. This is most often a minor EM. Herpes lesions precede EM for a few days (7 to 10 days). In contrast, all herpes outbreaks are not accompanied by EM, and some outbreaks of EM can be caused by asymptomatic herpes recurrences. Viral research is often negative at the moment of diagnosis. In the case of a recurrence of EM, herpes origin must be suspected. It is observed in 70% of cases of recurrent EM. In clinical practice, the diagnosis of herpes origin is mainly based on anamnesis.

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae should be systematically sought for treatment in children. EM complicates 2% to 10% of infections with Mycoplasma pneumoniae in children and most often has a mucosal involvement. It is responsible for about two-thirds of EM with mucosal involvement. It is advisable to systematically perform a chest x-ray in addition to bacteriological research, if possible by gene amplification (PCR).

- Other viral (adenovirus, influenza, Epstein Barr, hepatitis virus, Coxsackie, parvovirus B19, human immunodeficiency virus) and bacterial (tuberculosis, streptococci) infections were incriminated.

EM cases have been attributed to some pediatric vaccines. The link is frequently controversial with regard to the large number of vaccines and the rarity of this association.

Blood work may reveal mild leucocytosis, neutropenia, and mild anemia. Electrolyte values may be altered if the patient is dehydrated or has developed renal failure.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of the Acute Phase

- Topical treatment is based on antiseptics for bullous lesions, antiseptic mouthwashes, and anesthetic. Ophthalmologists manage ocular involvement. Healing is promoted by the application of vaseline on the lips and vitamin A ointment in the eyes.

- Hospitalization is needed in case of the inability to eat, pain control, or hydration. The role of systemic corticosteroids and intravenous immunoglobulins has been discussed without demonstrating their effectiveness. Daily monitoring is necessary in cases of extensive lesions.

- Etiological treatment must be instituted when a cause (or sometimes probable) is identified. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection justifies treatment with azithromycin for three days without even waiting for the results of the bacteriological examinations, especially if there is a cough or pulmonary radiological abnormalities. Some suggest treating with aciclovir or valaciclovir if herpes is suspected.

Prevention of Recurrent EM Form

- Herpes is the most common cause. Even if specimens have not established the evidence, long-term treatment with aciclovir or valaciclovir should be proposed.

- It is indicated, in theory, for patients with more than 5 EM outbreaks per year or fewer in the case of EP severe forms. Valaciclovir treatment prevents HSV-induced EM outbreaks but appears to have no impact on an EM outbreak if it starts after the beginning of the eruption.

- If no etiology is identified, other therapeutics may be proposed in the long term, such as hydroxychloroquine, dapsone, or early treatment of sprouts by systemic corticosteroids.[9][10][11]

Admission

Severe cases of EM will require admission to manage the complications, dehydration, and any infection. These patients are best managed in an ICU and treated like a burn-patient. However, debridement should be avoided while the lesions are progressing. The eroded lesions should be bathed in Burrow's solution or saline with non-adherent dressings. All offending drugs must be immediately discontinued. While one may apply silver nitrate, silver sulfadiazine should be avoided because it may worsen the injury. Re-epithelialization can take 7 to 21 days. Nutrition support is vital, and if the patient has diarrhea, TPN is an option. Central lines should be avoided to lower the risk of infection, and strict asepsis should be practiced. Hypothermic patients may require a warming blanket, warmed IV solutions, or a heating lamp. Deep venous thrombosis and stress ulcer prophylaxis is highly recommended.

Differential Diagnosis

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS): It affects up to 10% of the body surface area, a larger area than in EM. The mucosal involvement is similar. The cutaneous involvement differs from EM by the absence of typical targets and the predominantly axial disposition. The target-like lesions are asymmetrical and made of two concentric zones and purpuric evolution. A drug origin is most often involved, and the outcome is more severe since it can progress into Lyell syndrome, unlike EM. Behçet disease can cause erythema multiforme-like lesions.

Staging

Erythema multiforme minor (EMm) essentially touches the skin with typical lesions and symmetrical acral disposition. The mucosal involvement is rare, and when it is present, it is light and affects a single mucosa, often the mouth.

In Erythema multiforme major (EMM), the skin lesions are more extensive but do not exceed 10% of the body surface area. Typical target lesions are present. The mucosal involvement is severe and affects at least two different mucosal sites; the oral mucosa is typically affected.

Prognosis

The prognosis is mainly related to the body surface area detached. The healing is obtained spontaneously in 2 to 3 weeks for the EMm and 4 to 6 weeks for the EMM. The mucosal lesions always take longer to heal. The healing of the mucocutaneous lesions is without scarring but with frequent dyschromia. Recurrences are seen in less than 5% of cases, mainly in forms due to herpes infection.

The main long-term risk is the development of synechias in case of mucosal involvement. Ocular sequelae can be serious, leading to blindness. At the genital level, synechiae can produce functional sequelae.

Particular vigilance during the acute episode must be implemented to prevent these sequels. The vital prognosis is only exceptionally brought into play when the care is adapted. Two situations that deserve particular vigilance are (1) severe mucosal involvement and (2) bacterial superinfections.

Poor prognostic factors include renal dysfunction, prior bone marrow transplant, visceral involvement, and advanced age.

Unfortunately, some patients may develop continuous EM, which is recalcitrant to treatment. This may occur in patients with HSV infection, reactivation of EBV, inflammatory bowel disease, and occult renal cell cancer.

Complications

While mucosal lesions heal completely, the skin lesions may result in scars. In addition, strictures of the urethra, esophagus, vagina, and anus are not uncommon. Urinary retention, phimosis, and hematocolpos have all been reported as a result of strictures. Eye complications occur in up to 20% of patients and can result in uveitis, conjunctivitis, scarring, panophthalmitis, and permanent blindness. Epiphora can result if the nasolacrimal duct is narrowed. Many patients develop dry eye syndrome and corneal scarring.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of EM is best done with an interprofessional team. While the dermatologist often makes the diagnosis, the follow-up of these patients is with the primary care provider and nurse practitioner. The following specialties should be involved in the care of the patient:

The pharmacist should ensure that the patient is on no medication that can worsen EM and that all offending medications have been discontinued.

The dermatologist should be consulted if the diagnosis is in doubt.

An ophthalmologist should be consulted if the eyes are involved.

A burn surgeon should help manage critically ill patients.

The infectious disease specialist should provide a guide to the treatment of any viral, fungal, or bacterial infection.

If the lungs are involved, a respiratory therapist should be involved.

The physical therapist should be involved in exercising the patient and restoring joint function.

Since the patient can develop severe scars and poor aesthetics, a mental health nurse should provide counseling.

In general, supportive care will suffice for most patients. Patients need to be educated about general skin care. Once the primary condition is managed, EM resolves. However, time healing may take weeks or even months. Particular vigilance during the acute episode must be implemented to prevent these sequels. The vital prognosis is only exceptionally brought into play when the care is adapted. Two situations that deserve particular vigilance are (1) severe mucosal involvement and (2) bacterial superinfections. [12] [Level 5]