Continuing Education Activity

Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin is caused by the cumulative exposure of the skin to UV light. This neoplasm has a precursor lesion, actinic keratosis, which exhibits tumor progression and metastatic potential. Surgical excision is the preferred therapeutic intervention for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Mohs micrographic surgery is the preferred surgical modality for lesions on the head and neck and in other high-risk areas or for lesions with high-risk characteristics. Radiation therapy is employed to treat cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in older patients, those who are poor surgical candidates, or when it has been impossible to obtain clear surgical margins. Patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma should be examined regularly and employ measures to protect their skin from UV damage.

This activity for healthcare professionals reviews the etiology, epidemiology, pathophysiology, histopathological findings, clinical evaluation, and management of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in improving outcomes for patients with this form of skin cancer.

Objectives:

Identify patients at risk for squamous cell carcinoma of the skin based on their clinical history.

Implement effective screening protocols for patients with cutaneous UV damage.

Apply best practices when treating patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.

Develop effective interprofessional team strategies to improve patient education about effective methods to reduce the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin.

Introduction

Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, also known as cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, is the second most common form of skin cancer in the United States; basal cell carcinoma is the most common. Squamous cell carcinoma has a precursor lesion, actinic keratosis, which exhibits tumor progression. Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin has the potential to metastasize but does so rarely. The primary risk factor for the development of actinic keratoses and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin is UV solar radiation; lifetime cumulative exposure to UV radiation plays a significant role in the development of this neoplasm.

Surgical excision is the primary treatment modality for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma; Mohs micrographic surgery is the preferred therapeutic technique for lesions of the head, neck, and those with high-risk characteristics in other anatomical regions. Radiation therapy is reserved for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in older patients, those who are poor surgical candidates, or when it has been impossible to obtain clear surgical margins.

Immunosuppression significantly increases the lifetime risk of developing cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma; the risk of metastasis is increased in immunosuppressed patients. Patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma should be examined regularly, and protective measures should be employed to avoid UV damage.[1][2][3]

Etiology

UV solar radiation is the most common cause of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. However, long-term exposure to carcinogens, such as tar in cigarettes, can also lead to the development of squamous cell carcinoma. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma may arise in scars from severe burns or long-term ulcerative skin lesions. High-risk subtypes of the human papillomavirus (HPV) are considered a risk factor for the development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, especially in the genital area.[4][5]

Epidemiology

Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin is prevalent, and more than one million cases are diagnosed in the United States annually. Historically, the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma was thought to be 3 times that of basal cell carcinoma; more recent studies suggest that the incidence is fairly even. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma occurs more frequently with increasing age, particularly in individuals older than 50. This neoplasm is slightly more common in men and individuals of both sexes with light-colored skin and eyes.

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma typically arises in anatomical regions with increased levels of UV radiation from either the sun or medical treatment. Squamous cell carcinoma is also very prevalent in immunosuppressed patients, where the incidence of aggressive subtypes is increased.[6][7][8]

Pathophysiology

UV radiation is the accepted major risk factor for the development of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Mutations in tp53 are the most common genetic abnormalities found in actinic keratoses, squamous cell carcinoma in situ, and invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Tanning lamp or bed usage, therapeutic UV exposure, and ionizing radiation are all well-known risk factors for the development of squamous cell carcinoma, likely through the p53 pathway. Mutated p53 allows cells with DNA errors to complete the replication cycle.

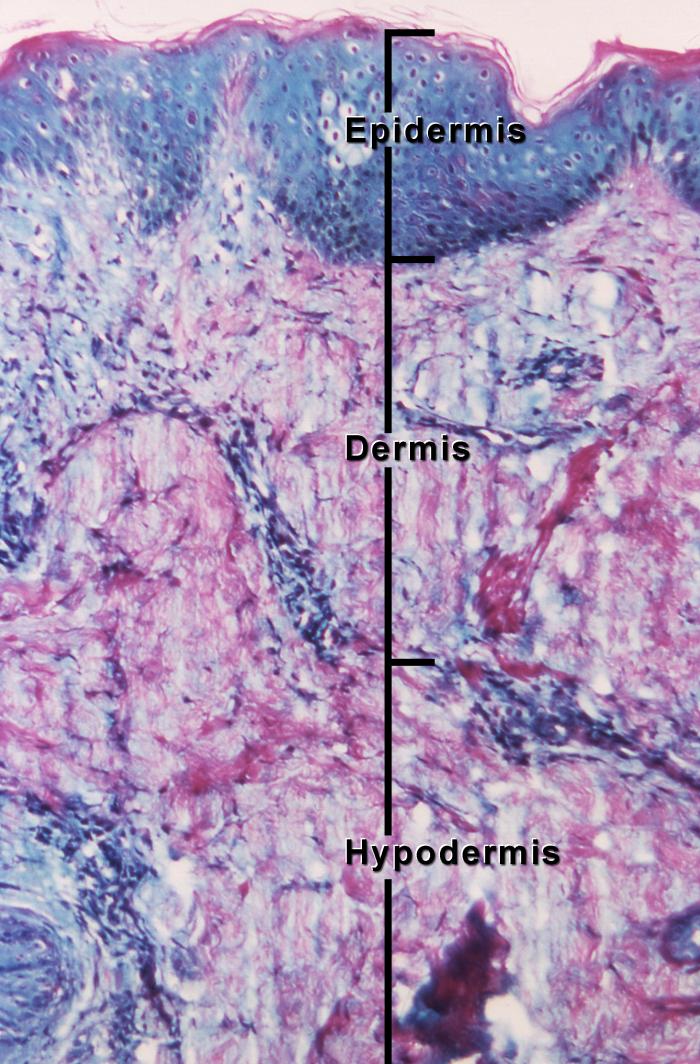

Histopathology

The histological subtypes of squamous cell carcinoma include squamous cell carcinoma in situ, Bowen disease, acantholytic/adenoid/pseudoglandular, clear cell, sarcomatoid/spindle cell, keratoacanthoma, and verrucous carcinoma. Squamous cell carcinomas classically consist of atypical keratinocytes with abundant eosinophilic or glassy-pink cytoplasm. Parakeratosis, intercellular bridging, and keratin pearls are other common findings.[9] Histopathologically, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is characterized by irregular nests, cords, and sheets of neoplastic keratinocytes invading the dermis. Lesion thickness is of particular importance when predicting risk for metastasis, with a thickness of more than 4 mm associated with a higher risk. Immunoperoxidase staining for cytokeratins 5/6/AE1/AE3 is useful in situations where the diagnosis is in question, especially with poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma.[10][11]

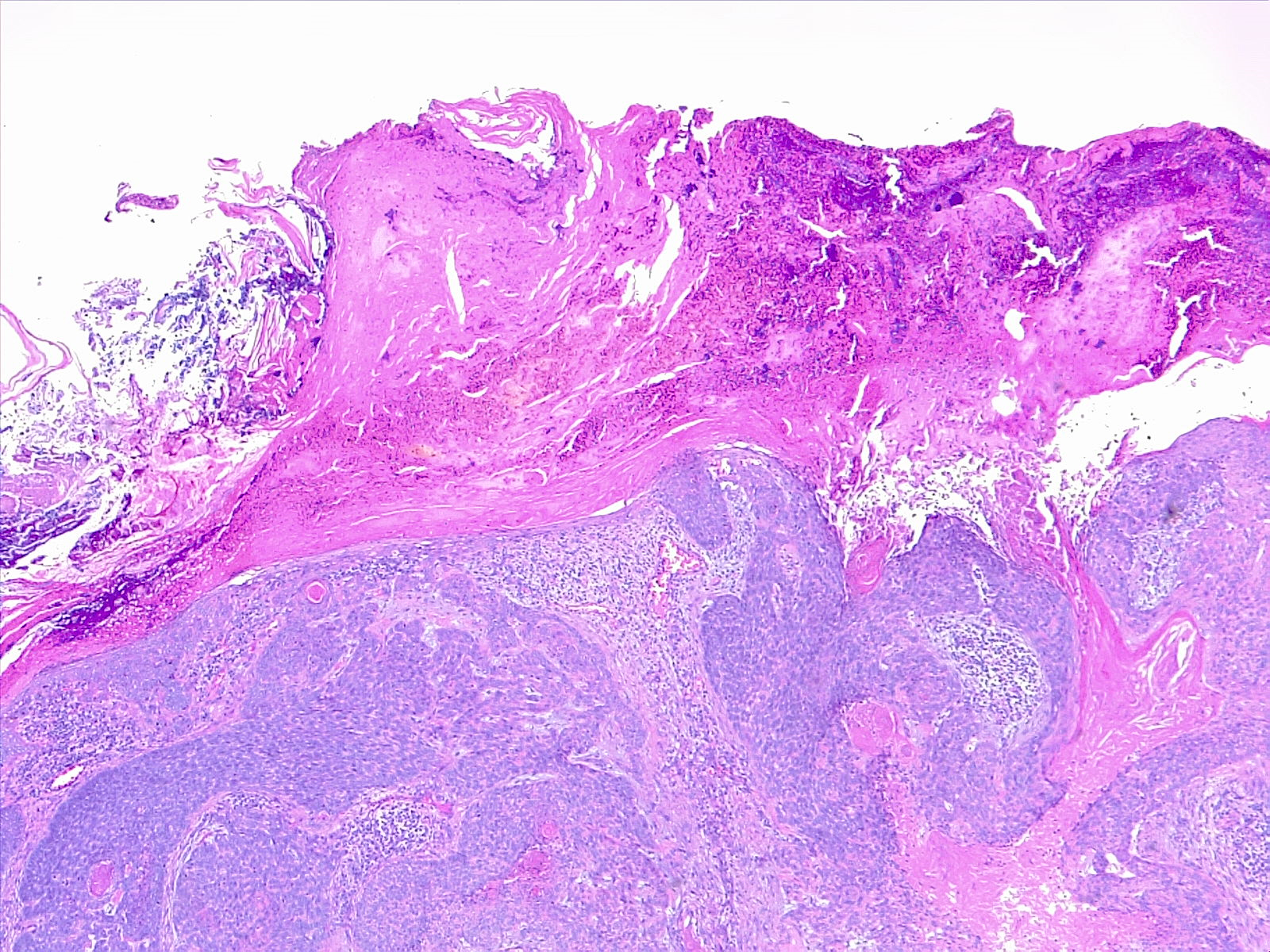

The acantholytic/adenoid/pseudoglandular subtype of squamous cell carcinoma is characterized by clefting around nests or cords of plump, polygonal tumor cells, often creating a glandular appearance (See Image. Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Acantholytic). Clefting is due to desmosomal disruption. In contrast to tumors of true glandular origin, such as adenosquamous carcinoma, CEA staining of acantholytic lesions staining is negative.[9]

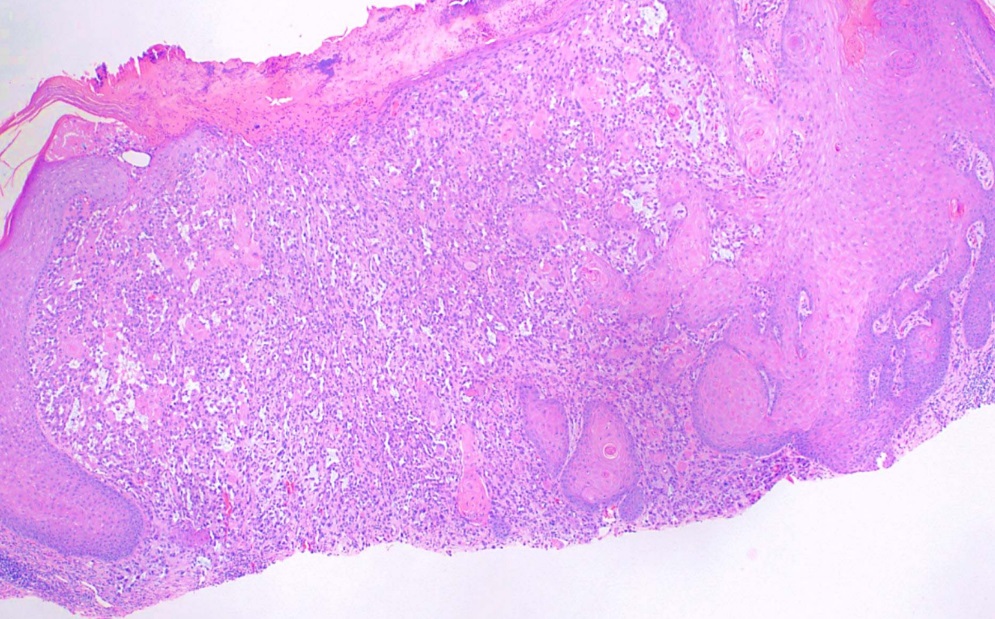

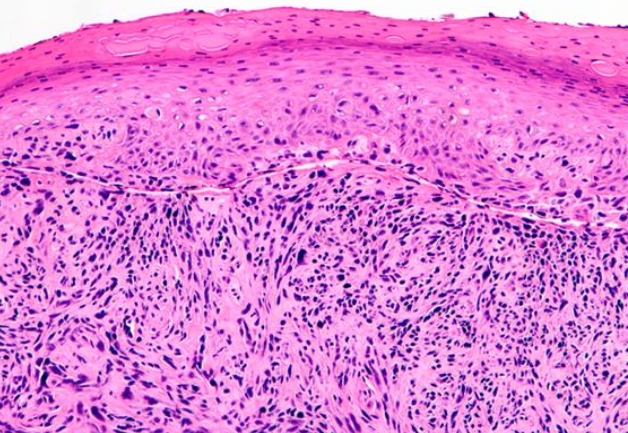

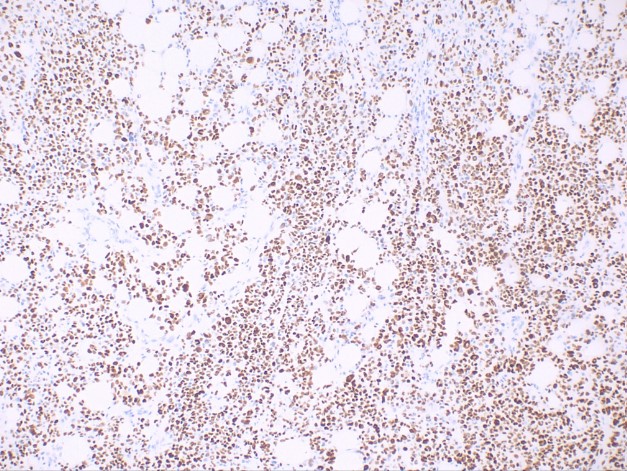

The sarcomatoid/spindle cell subtype of squamous cell carcinoma is characterized by spindle-shaped keratinocytes with pleomorphic nuclei haphazardly arranged throughout the dermis with a typically infiltrative pattern (See Image. Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Sarcomatoid). Numerous mitotic figures may be observed. Atypical fibroxanthoma is an important histological differential that typically stains negative for p63 and p40, in contrast to sarcomatoid/spindle squamous cell carcinoma (See Image. Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Positive p40 Stain).[9] Immunohistochemistry of sarcomatoid lesions with p40 is reported to be more specific than with p63.[12]

Desmoplastic squamous cell carcinoma may appear similar to the sarcomatoid variant. However, desmoplastic lesions are characterized by a desmoplastic or densely collagenous stroma in greater than 30% of the tumor. Perineural invasion has been frequently reported. Desmoplastic melanoma is also in the histological differential diagnosis, but desmoplastic squamous cell carcinoma classically stains positive for p63 while negative for S100; this is a helpful distinguishing factor.[9]

Verrucous carcinoma is characterized by verruciform acanthosis with blunt, broad projections abutting the dermis. HPV=related cytomorphology is less evident than that seen in benign warts.[9]

For a more comprehensive discussion of the histopathological findings of certain squamous cell carcinomas of the skin, please see StatPearls' companion references "Intraepidermal Carcinoma," "Clear Cell Acanthoma," and "Keratoacanthoma."

History and Physical

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma typically arises in a background of sun-damaged skin, often from precursor actinic keratoses. The most common anatomical areas where the neoplasm occurs are the face, neck, bald scalp, extensor forearms, dorsal hands, and shins. The color of the lesions varies from flesh-toned to erythematous with variable degrees of scale, crusting, ulceration, and hyperkeratosis. Occasionally, telangiectases with or without active bleeding may be present. Squamous cell carcinoma can be flat, nodular, or occasionally plaque-like, with significant induration or palpable subcutaneous spread (see Image. Squamous Cell Carcinoma). Squamous cell carcinoma may be painful and tender, which may be signs of perineural invasion.

Evaluation

A skin biopsy is mandatory in all patients with suspected cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.

Treatment / Management

The preferred therapeutic intervention for squamous cell carcinoma of the skin is surgical excision. Mohs micrographic surgery is the treatment of choice for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Mohs Surgery is also the treatment of choice for squamous cell carcinoma in immunosuppressed patients, recurrent lesions, lesions with aggressive histologic features, and lesions greater than or equal to 2 mm in depth.

The treatment of actinic keratosis with focal squamous cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in situ is dictated by the clinical circumstances and histologic findings. If pursued, treatment may include Mohs micrographic surgery, curettage, or excision. To aid decision-making, the American Academy of Dermatology has developed guidelines available as a smartphone app listed under “Mohs Appropriate Use Criteria (AUC).” These guidelines assist in selecting those cases that would most benefit from the Mohs procedure while conserving health care expenditures. Other therapies for these lesions include oral or topical retinoids to help reduce the risk of progression to squamous cell carcinoma. Photodynamic therapy and topical 5-fluorouracil or imiquimod may also be used to decrease the risk of progression. For in situ disease, electrodesiccation with curettage or topical therapies have been used successfully.[13][14][15]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma comprises myriad cutaneous lesions including but not limited to:

- Actinic keratosis

- Basal cell carcinoma

- Melanoma

- Burns

- Scar tissue

- Pyoderma gangrenosum.

Staging

High-risk features of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma include:

- Perineural invasion

- Thickness of lesion greater than 2 mm

- Lesion on the ear

- Poorly differentiated lesion.

Prognosis

Small cutaneous squamous cell lesions can be excised and are not fatal. However, even small neoplastic lesions can contribute to significant morbidity depending on their location. Most cutaneous squamous cell cancers around the head and neck region require complex surgical excision; poor cosmetic outcomes are common. Advanced cutaneous squamous cell cancers have a poor prognosis with a 5-year survival rate below 40%. Recurrence following excision of a large lesion is reported in 10% to 18% of cases.[16][17]

Complications

The complications of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin include but are not limited to:

- Metastases

- Local invasion

- Pain

- Loss of function

- Poor aesthetics

- Death.

Consultations

A dermatologist with Mohs micrographic surgical credentials typically manages cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Depending on the characteristics of the lesion and the stage of the disease, consultation with medical oncology or radiation oncology may be required.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma should be counseled to protect their skin from further UV damage through the use of sunscreen, protective clothing, and avoidance of the sun during periods of maximal intensity. Tanning beds should be avoided protective clothing should be worn, particularly on the arms and upper body. Avoiding sun exposure between 10 am and 4 pm significantly decreases UV exposure.

Also, they should be followed regularly, with the actual frequency based on their frequency of squamous cell carcinoma development. Patients with a history of a few squamous cell carcinomas and some actinic keratoses may be evaluated every 6 to 12 months. In contrast, those with many squamous cell carcinomas or aggressive tumors will need to be seen much more often.

Pearls and Other Issues

Lifetime avoidance of UV damage is of the utmost importance in preventing squamous cell carcinoma. Daily application of sunscreen above 30 SPF has been shown to decrease the risk of developing actinic keratoses and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. If a clinician suspects a skin lesion is squamous cell carcinoma, immediate tissue biopsy is recommended.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The majority of skin cancers can be prevented through education about the importance of avoiding UV damage. Using sunscreen daily and avoiding excessive sun exposure is paramount. Education can and should be provided by all healthcare professionals, including medical assistants and nurses. All patients should be taught how to perform a skin examination and see a healthcare provider for any skin lesion that suddenly changes in its growth or shape. There is no evidence that the use of herbs or other supplements can prevent skin cancer, and the patient should be told not to rely on these treatments.[18][3]