Introduction

The parathyroid glands are endocrine glands located in close association with the thyroid gland in most patients. There are normally four individual parathyroids, though supernumerary parathyroids have been found in up to 13% of autopsies[1]. There are two glands located superiorly called the superior parathyroid gland and a pair that are located inferiorly- referred to as the inferior parathyroid glands. Ectopy of one or more parathyroids is relatively common, with a meta-analysis revealing up to 16% of glands may be in an ectopic location including the mediastinum, retro-esophageal area, or other aberrant locations in the lateral neck[1].

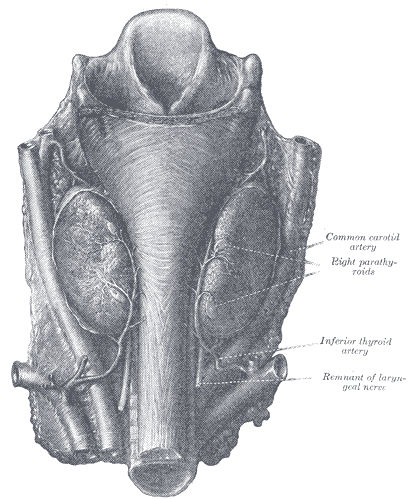

Superior parathyroid glands: These glands derive from the fourth pharyngeal pouch. They are classically located near the posterolateral aspect of the superior pole of the thyroid, 1cm superior to the junction of the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN), and the inferior thyroid artery. They classically lie deep to the plane of the recurrent laryngeal nerve.

Inferior parathyroid glands: These glands derive from the third pharyngeal pouch. These glands are classically located near the inferior poles of the thyroid glands, within 1-2 cm of the insertion of the inferior thyroid artery into the inferior pole of the thyroid. They classically lie superficial to the plane of the RLN. Their location is much more variable than the superior parathyroids, and can be intra-thyroidal or within the thymus or other mediastinal structures, and can even be found along the aortic arch.[2]

Structure and Function

The parathyroid glands have two distinct types of cells: the chief cells and the oxyphil cells.

- Chief cells: The chief cells manage the secretion of parathyroid hormone (PTH). When the cells are viewed, they contain prominent Golgi apparati and a developed endoplasmic reticulum to help with the synthesis and secretion of the hormone. While the chief cells are smaller than the oxyphil cells, they are more abundant.

- Oxyphil cells: The purpose of these cells is not entirely understood. They are larger than the chief cells and seem to increase in number with age.

Function

The parathyroid glands help regulate the calcium level in the blood. When the calcium levels in the blood decrease, the parathyroid gland releases a hormone called parathermone or parathyroid hormone (PTH). PTH is initially produced as a polypeptide hormone that is initially excreted as pre-proparathyroid hormone (115 amino acids), then becomes a proparathyoid hormone (90 amino acid) and eventually to the final form which comprises 84 amino acids, parathermone (PTH). When secreted, PTH affects select target organs including the kidneys, intestine, and the skeletal system.

- Kidney: PTH promotes calcium reabsorption and excretion of phosphate. The reabsorption is promoted at the ascending loop of Henle, distal tubule, and the collecting tubules. The prevention of phosphate reabsorption occurs at the proximal tubule. PTH also promotes 25-hydroxyvitamin D conversion to its active form (1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D-3) via activation of 1-hydroxylase in the proximal tubules.

- Intestine: Activated vitamin D promotes the absorption of calcium due to the increased formation of the calcium-binding protein in the intestinal epithelial cells.

- Bone: Rapid Phase- PTH affects both osteoblastic and osteoclastic cells. When PTH binds to the cellular receptors, it allows the pumping of calcium from the osteocytic membrane. This causes an immediate effect and allows for the rise of calcium to occur within minutes. Slow Phase: The slow phase takes several days to precipitate an increase in blood serum calcium. This process occurs via the osteoblast, as mature osteoclasts do not have receptors for PTH. This activation of the mature osteocytes by the osteoblast is via cytokines. The proliferation of osteoclasts also occurs.[3]

PTH Regulation

Increase of Blood Calcium

PTH regulation is via a negative feedback loop via the Chief cells' unique G- protein calcium receptor. An increase in blood calcium allows the calcium to bind to G protein and increase the production of phosphoinositide molecules. This molecule prevents the secretion of PTH. Vitamin D also acts directly on the gland to decrease the transcription of the PTH gene leading to decreased PTH synthesis.

Decrease of Blood Calcium

When there is a detected decrease in blood calcium, there is less calcium binding to the G-protein of the chief cells. This decreased binding subsequently leads to a decreased production of the phosphoinositide molecule allowing increased secretion of PTH. A decrease in vitamin D permits an increase in PTH synthesis due to the activation of the transcription of the PTH gene.[4]

Embryology

The parathyroid glands originate from the third and fourth pharyngeal pouches of the endoderm, with contributions from the neural crest and the ectoderm. At six weeks in which there is an elongation of the pouch. The pouch is initially hollow, but with further development, cell proliferation occurs allowing for solidification and subsequent migration. [5]

The inferior parathyroids originate from the third pharyngeal pouch, and the superior parathyroid arises from the fourth pharyngeal pouch. The fetal parathyroid hormone cells respond to calcium levels; fetal calcium levels are higher than maternal calcium levels.[2][6]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The thyroid gland and the parathyroid glands share the same blood supply. The inferior thyroid arteries supply the parathyroid glands via its branches (supplying both the inferior and superior parathyroids in most cases). Collaterals via the superior thyroid artery, thyroid ima artery, laryngeal, tracheal, and esophageal arteries. Parathyroid veins drain into the thyroid vein plexus.

Parathyroid lymphatic vessels drain in the deep cervical and paratracheal lymph nodes.

Nerves

The nerve supply of the parathyroid derives from the branches of the cervical ganglia of the thyroid gland. The nerve supply to the parathyroid glands is vasomotor.

Surgical Considerations

Parathyroid glands can have inconsistent locations between individuals and these locations can vary widely. Due to these variants, damage to the glands can occur during neck surgery, especially thyroidectomy. An essential component of a safe thyroidectomy is the identification and preservation of as many parathyroid glands as possible. While, in theory, a portion of a single parathyroid gland should be sufficient to maintain serum calcium homeostasis, it is prudent to identify and preserve all glands. If this is not possible, such as in thyroid cancer surgery for very advanced disease, where oncologic safety requires a comprehensive, en bloc, resection, patients must be counseled preoperatively that lifelong calcium and vitamin D supplementation may be required. Thankfully this is very rare, and experienced surgeons can routinely identify and preserve the glands. Removal of both pairs of the parathyroid gland is extremely uncommon and would cause a decrease in the serum calcium levels, leading to the development of tetany, cardiac arrhythmias, and a host of other untoward effects if left untreated.[7][1]

Removal of Parathyroid Gland Due to Pathologies

A hyperfunctioning parathyroid gland often requires surgical intervention. When the parathyroid over-secretes PTH, there are risks associated with elevated serum calcium. However, many patients present with incidentally discovered hypercalcemia. These patients may only require monitoring, and even mild symptoms can be medically manageable. These "biochemically" hyperparathyroid patients (who are otherwise asymptomatic) present an ongoing conundrum: some nephrologists recommend parathyroidectomy, while others recommend medical management. However, when there are symptoms present due to hypercalcemia, surgical intervention is definitely indicated.[8]

Bilateral Neck Exploration

When surgery is considered the most traditional technique is bilateral neck exploration. During this procedure, the surgeon will locate all four of the glands and based on appearance will determine if partial or complete glandular removal is necessary. This is especially important in cases of secondary hyperparathyroidism in patients with renal failure. Intra-operative rapid PTH monitoring is a useful tool if it is available.

Focused Parathyroidectomy

Another less invasive approach can potentially allow a more limited operation of the diseased gland. This allows the surgeon to target the gland that has been identified after pre-operative localizing tests. Radiographic parathyroidectomy can be considered as a type of focused parathyroidectomy. The patient receives a small injection of Tc-99m sestamibi the morning of the surgery. A handheld gamma probe is employed in the operating theater by the surgeon to detect the hyperactive gland. After excision of the diseased tissue, the probe can be used again to detect if any overactive tissue remains. The rate of non-localizing scans is hugely variable and is dependent on the underlying pathophysiology. Thus, the prudent surgeon will always discuss with the patient the potential need for formal, four-gland exploration. Additionally, while a solitary parathyroid adenoma is the most common cause of localizable hyperparathyroidism, undetected double adenomas are reported in as many as 10% of individuals[9]. Intraoperative rapid PTH assay is similarly useful in these patients.

Clinical Significance

Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperparathyroidism is defined as the elevation of PTH due to overactivity of the parathyroid gland and leads to hypercalcemia in many cases. Hyperparathyroidism can be broken down into subsequent subgroups. [10] [11]

Primary: Primary hyperparathyroidism is due to direct gland alterations. This is most commonly due to a parathyroid gland adenoma, but can also be due to diffuse four-gland hyperplasia, malignancy, or multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) types 1 or 2. Excess secretion of PTH will present with hyperparathyroidism and may also present as hypercalcemia, hypoglycemia, osteoporosis, osteitis fibrosa cystica, and hypertension (particularly diastolic hypertension).

Secondary: This is a physiological increase of PTH due to reduced calcium levels in the blood. The most common cause is chronic kidney disease, but can also be due to vitamin D deficiency or malnutrition.

Tertiary: This occurs after prolonged secondary hyperparathyroidism. Due to the continuous chronic increase secretion of PTH, there are structural changes in the parathyroid glands causing them to lose the negative-feedback regulatory mechanisms and hyper-secrete PTH even if the underlying cause of secondary hyperparathyroidism has been corrected.

Malignant: Various tumors (bronchial squamous cell carcinomas) can produce a parathyroid-like protein that can mimic PTH function. Though the protein mimics PTH, reduction of actual PTH levels occurs due to the negative feedback to the parathyroid gland. This can be determined by measuring serum levels of both intact PTH and parathyroid-related hormone (which is produced by the tumor).

Hypercalcemia

Hypercalcemia can be the result of an overactive parathyroid gland. Symptoms can range from being non-existent to severe.

General

Kidneys

- kidney stones- leading to back and flank pain

- excessive urination

- excessive thirst

Abdomen

- vomiting

- constipation

- nausea

- decreased appetite

- abdominal pain

Heart

abnormal electrical rhythms

Muscle

Skeletal system

- fractures

- bone pain

- osteoporosis

Neurological symptoms

- memory loss

- irritability

- depression

- confusion

- coma

Hypoparathyroidism

Hypoparathyroidism is due to reduced activity of the gland. This condition has primary and secondary classifications.

Primary: There is a gland failure which results in a decrease in PTH secretion. Patients who suffer from this disorder will often need calcium supplementation

Secondary: This occurs when there is surgical removal/injury of the parathyroids. This can often be accidental during neck surgery or expected after more extensive neck surgery, such as a total laryngectomy with total thyroidectomy. Radiation therapy for various neck malignancies can also lead to the destruction of the parathyroids and subsequent hypoparathyroidism.[12]