Introduction

The tendon is a "mechanical bridge." It allows the transmission of muscle strength to the bones and joints. On the other hand, it enables the contraction of the muscle to make the final tangible movement. Different types of tendons reflect the morphology of the muscle and their specific function. Tendon tissue is not just about the terminal or initial area of each muscle but involves the entire muscular tissue. The connective layers (epimysium, perimysium, and endomysium) merge into a single organization to contact one or more fixed osseous points. The same tendon near the muscle has contractile fibers. The muscle affects the tendon, and the tendon affects the functional expression of the muscle.

Within the context of manual therapy, rehabilitation, or surgery, it is a mistake not to consider these close relationships between anatomy and function. Depending on the systemic hormonal environment and age, the tendon tissue can adapt its cellular structure under physiological (training) or pathological (traumatic) stimuli.[1][2]

Structure and Function

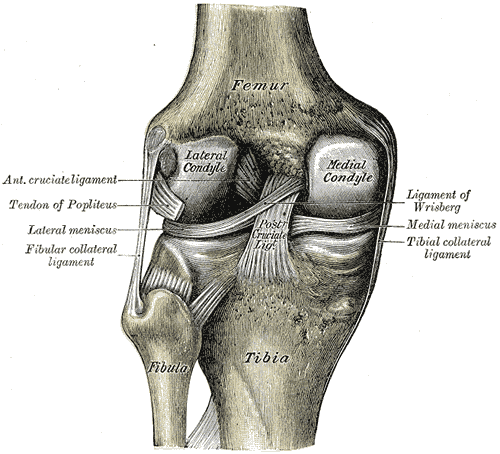

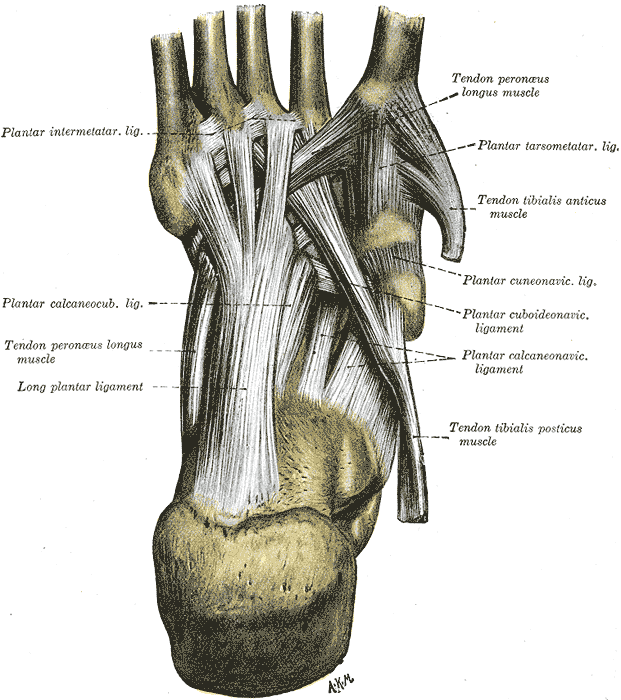

Tendons play an extraordinary role in mechanics and movement. They transmit the force produced by the muscular contraction to the skeletal levers, thus allowing for movement and the maintenance of the body posture. The tendons allow the muscle to be at an optimal distance from the joint on which it acts without requiring an excessive muscle length between the origin and the insertion points. Tendons are stiffer than muscles, have greater tensile strength, and can withstand very large loads with minimal deformations. These properties of the tendons make the muscles capable of transmitting forces to the bones without energy loss due to tendon stretch. For example, the flexor tendons of the foot can bear more than eight times the body weight and store about 40% of this weight for an elastic hysteresis during walking.[3][4][5][6]

Tendon Sheaths

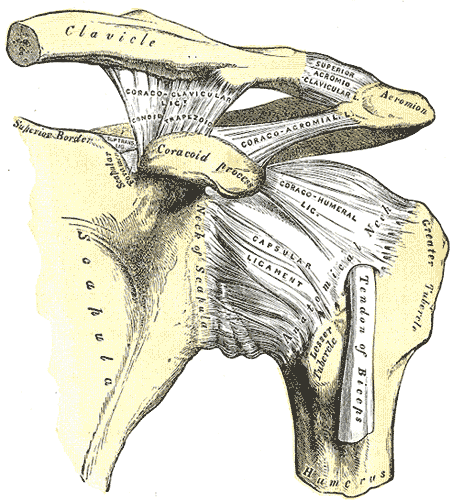

Tendon sheaths are satellite structures whose main task is to facilitate the sliding of the tendon tissue surrounding anatomical structures and prevent the tendon from losing its course of action during muscle contraction.

Fibrous Sheaths

The fibrous sheaths or retinacula represent the sliding channels of the tendons, particularly the long ones. Without fibrous sheaths, the sliding action on the neighboring tissues could be considerably compromised by friction, especially at bone structures. In these regions, there are tunnels in which the tendons flow, surrounded by a synovial sheath. In particular, the showers and bone incisions are generally covered by a fibrocartilaginous floor on which a fibrous fabric roof passes over a bridge. This structure represents the fibrous sheath or retinaculum, a formation found at the extremities. Typical examples are the retinacula of the flexor and extensor tendons of the hand and foot at the level of the wrist and the instep.

Synovial Sheaths

The synovial sheaths facilitate the sliding of the tendon inside the fibrous sheath. Synovial sheaths consist of two thin serous sheets: the parietal sheet that covers the walls of the fibrous sheath and the visceral sheet that covers the surface of the tendon. The two sheets continue at the level of the two ends of the duct. The closed space delimited by the two sheets contains a thin veil of liquid, the peritendinous liquid, which has roughly the same composition as the synovial fluid and serves mainly as a lubricant. In addition, peduncles of loose tissue detach themselves from the walls of the osteo-fibrous canals and terminate on the tendinous belly leading to the vessels and nerves of the tendons. These structures constitute the mesotenonium, are also covered by the synovium, and may be more or less numerous depending on the length of the tendon itself. However, not all tendons possess true synovial sheaths; they are found only in areas where a sudden change in direction and increased friction require very efficient lubrication.

Peritendon Sheaths (Paratenon)

The peritendinous sheets have a function that can be superimposed on that of the synovial sheaths, although they present a different histological structure. Paratenon comprises type I and type III collagen fibrils and thin elastic fibers. The paratenon reduces friction and works as a sort of elastic sleeve that allows the free movement of the tendon with respect to the surrounding structures.

Reflection Pulleys

Reflection pulleys are circumscribed thickenings of dense fibrillar tissue located along the course of the fibrous sheaths. They contain the tendon inside the sliding bed, especially where there are curvatures along the course of the tendon.

Tendon Bursae

Tendon bursae help to minimize friction between the tendon and adjacent bony structures. These bursae are small serous vesicles located in the sites where a bony prominence can compress and then wear out the tendon; typical examples are subacromial, infrapatellar, and retrocalcaneal bursae.

Below the paratenon, the entire tendon is surrounded by a thin sheath of dense connective tissue called epitenonium. Together, the paratenon and epitenonium can be called peritenonium. Within the epitenonium, the collagen fibrils are oriented transversely, longitudinally, and obliquely. Occasionally the epitenonium fibrils appear to be fused with the superficial tendon fibrils.

On its external surface, the epitenonium is contiguous to the peritenonium. The inner surface is in continuity with the endotenonium, a thin membrane of loose connective tissue that covers the individual tendon fibers and groups them in larger units represented by bundles of fibers of various order. The function of endotenonium is to circumscribe, individualize the various orders of bundles, and allow the penetration and the capillary distribution of neurovascular structures inside the tendon.

The point where the muscle pierces in the tendon is called the musculotendinous junction. The point where the tendon inserts on the bone is called the osteotendinous junction.

Cell Population and the Extracellular Matrix

Two specialized fibroblasts co-exist in the tendinous tissue: tenocytes and tenoblasts. The tenocytes have an elongated shape, while the tenoblasts have an ovoid shape. Tenoblasts represent approximately 90% to 95% of tendon fibroblasts. When a tendon is injured, healing occurs via multiple overlapping phases. During the tendon healing phase, tenoblasts are involved in tissue repair, depositing collagen fibers. During the last phase of repair, the tenoblasts are transformed into tenocytes.

These specialized fibroblasts produce extracellular matrix containing collagen, proteoglycans, and other proteins. Collagen makes up approximately 65% to 80% of the extracellular matrix. The prevalent collagen in tendons is type I. Type III collagen is present in the epitenonium and the endotenonium. Type II is identifiable in the fibrocartilaginous areas of the osteotendinous junction. Elastin, proteoglycans, and glycoproteins constitute 4%, 4%, and 2%, respectively, of the extracellular matrix.

Within the tendon, the collagen fibers comprise a variable number of fibrils arranged in parallel and joined together in fibers, always parallel to each other and the tendon axis. The bundles of collagen fibers show a wavy pattern, with periodic changes of direction, known in the literature as crimps. Crimps differ in size and geometry within the same tendon, appearing as isosceles or scalene triangles of variable size. The single crimp, observed by scanning electron microscope, appears to consist of rectilinear fibrillary segments tightly packed together and joined by nodes or hinges, in correspondence of which all the fibrils of each fascicle change simultaneously direction. In changing their course, the fibrils do not describe a loop but are deformed as a hollow cylindrical structure would do. Collagen bends but does not break.

Mechanical Properties

The biomechanical behavior of a tendon is related to the magnitude of tension stress and the shape of the tendon itself. Muscles used to perform delicate and precise movements, such as the flexors of the fingers, possess long and thin tendons. In contrast, those that perform actions of power and endurance, such as the quadriceps femoris and the triceps surae, have shorter and more robust tendons. A short tendon has a greater tensile strength than a long tendon because the load required to produce the break is much more significant in a short tendon with the same diameter.

A long tendon can undergo a greater deformation than a short tendon before undergoing rupture. The strength and resistance of a tendon are two different properties and depend on the diameter and length of the tendon itself. The biomechanical properties of the tendon are related to the diameter and arrangement of collagen fibrils; tendons subjected to high stress are fibrils of a large diameter, less flexible than those of smaller caliber.

The ability of the tendons to amortize and transmit the force of muscle contraction is also closely related to the tendon crimp. Researchers observe that greater tendon load correlates with a greater angle at the base of the crimps. When a tendon is stretched, the crimps gradually flatten. They act as a shock absorber in the tendon during the early stages of pulling, allowing the tendon to recover its form at the cessation of the applied force. The crimps do not flatten simultaneously but gradually from the periphery to the center.

Adaptation to Mechanical Stress

Tendinous adaptations appear to differ between genetic sexes. When subjected to repeated mechanical stress, genetic females develop less tendon strength than genetic males. However, tendon lengthening is more pronounced in genetic females. The reasons for this are not well understood.

Tendinous tissue adapts itself to the surrounding mechanical environment. Adaptation is specific to the imposed stress. When subjected to mechanical tension (contraction and muscle release), collagen synthesis increases, increasing tendon diameter. With continued tension, tendon stiffness will increase, as will the Young modulus. The Young modulus is the ratio of tensile stress to tensile strain, expressed in pressure units. This ratio defines how easily the tendon can stretch and deform.

Adaptation to Age

Tendon adaption capacity decreases with age. Age brings alterations to cellular structure with a diminished capacity for regeneration. Additionally, the tendon is less able to adequately pilot the force expressed by the muscle toward the bone tissue. Collagen fibers are less organized, and calcification can occur. There are fewer fibroblasts and senescent cells, a decrease in the amount of water, and a decrease in the number of proteoglycans, all of which contribute to a reduction in viscoelastic properties. These changes weaken the tendon and increase susceptibility to trauma.

Decreasing estrogen levels accompanying normal aging in the genetic female loosens the tendinous tissue, making it more prone to traumatic injury and the resulting inflammatory response.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Tendons have a complex vascular supply. Supplying vessels may come directly from the muscular belly and the periosteum surrounding the osteotendinous junction. If peritendinous leaflets or a synovial sheath are present, those vascular networks also feed the tendon.

The circulatory network of peritendinous leaflets varies both within the same tendon and between different tendons. Primary trunks may be arranged in a regular mesh structure; in other cases, they form concentric arches and are irregularly arranged. These vascular networks consist of small and medium-caliber arteries accompanied by one or two satellite venous anastomoses.

Within tendons, three different types of microvascular capillary units can be found. In one type, the capillary travels a long distance with a direction parallel to the longitudinal axis of the tendon, then becomes recurrent, looping back on itself to flow into a venule. Alternatively, a single arteriole will give rise to several capillary loops that run in different planes within the tendon. Yet another type acts as an arterio-venous shunt characterized by very short capillaries with a straight course. The presence of multiple types of microvascular units facilitates gas and metabolite diffusion within individual tendon bundles.

Tendinous lymphatic drainage exists as a network, with lymph draining toward tendon veins or to other neighboring venous structures.

When a tendon is subjected to mechanical stress, the blood flow to the tendon increases. However, lymphatic drainage does not increase proportionally to mechanical stress.

Nerves

Tendons are innervated by nerve branches from both the muscle belly and the sensitive branches distributed to the skin. Innervation is scarce. Nerves are localized to the paratenon, endotenon, and epitenon.

Nerve branches form trunks parallel to the tendon's central axis, anastomosed with branches with a transverse and oblique course. The nerve endings are of various types; some end in the musculotendinous organs of the Golgi or the corpuscles of Pacini or Ruffini, while others terminate in free arborizations. Innervation accompanies the vascular supply.

The sympathetic innervation of a tendon follows the vascular supply and stimulates vasoconstriction. Vasodilation is stimulated by either sensory fibers similar to parasympathetic fibers or by separate small-diameter sensory fibers.

Clinical Significance

Tendinopathy results in vascular changes and adaptations to the macroscopic and microscopic environment of the muscle and tendon. Increased vascularization is due to hypertrophy and hyperplasia, which occurs in the presence of an angiogenic cytokine such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Inflammation due to injury increases the local concentrations of VEGF. The increase in blood flow decreases the strength of the tendon with a reduction in the sliding capacity of the different connective layers. The same increase in nerve fibers occurs superficially in the tendon and toward the inside; nociceptive fibers also increase, causing pain.[7][8][9][10]

There is an increase in sympathetic nerve fibers near the blood vessels. It is hypothesized that altered tenocytes can synthesize nociceptive neurotransmitters, which will then be recorded by the sympathetic system with the onset of pain.

Enlers-Danlos Syndrome

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) is a group of genetically-based connective tissue disorders that affects the skin and the mobility of joints due to abnormal collagen synthesis. Collagen gives strength and elasticity to connective tissues, including tendons and joint components, skin, and blood vessels. The incidence of EDS has been estimated at 1 in 5000 cases, or 1% to 3% of patients.[11][12] The condition develops in childhood but is often not diagnosed until later in life.

The clinical manifestations of EDS vary widely, and the disease varies in severity. Diagnosis of EDS is based on physical examination and observation of the patient’s movements, as well as the patient’s medical history.[13] Symptoms may include abnormal scar formation, stretchy skin, and loose joints.

Joint hypermobility or laxity is one of the most characteristic signs of EDS. Small joints are typically more affected than large joints. The condition is often painful, and joint dislocations and sprains are common. Other complications of EDS include scoliosis, osteoarthritis, chronic pain, and aortic dissection.

As aforementioned, EDS is a group of disorders. There are currently 13 identified subtypes, with 19 known causal genes, each involved in developing the extracellular matrix and collagen. Inheritance is often manifested in an autosomal dominant manner. Collagen abnormalities are present in most known variants of EDS.

Classical EDS (types I and II) is characterized by abnormal type V collagen production. Vascular EDS (type IV) exhibits abnormal type III collagen. EDS type VII exhibits deficiencies in type I collagen. The genetic and biochemical basis of the most common variant[11] of EDS III (also known as hypermobility EDS) is unknown.[14]

Diagnosis of EDS is difficult because joint hypermobility is multi-factorial; gender, age, training, and body weight are all contributing factors.[11] Hypermobility EDS patients exhibit joint hypermobility, dislocation, and cutaneous manifestations. Additional symptoms include chronic pain, fatigue, anxiety, and dysautonomia.[11] The musculoskeletal pain of hypermobility EDS is often diagnosed as fibromyalgia.

Pain is a common symptom of EDS.[15] In childhood, it may present as variable arthralgia. Concurrent pain patterns may involve paresthesias, burning sensations, allodynia, cramps, and myalgias and may indicate that the condition has a neurological basis in addition to joint and skin pathologies. Neuropathy of the small fibers is common.[15] Pain can be classified as nociceptive (caused by stimulation of pain receptors) or neuropathic (caused by a malfunction within the nervous system). Although musculoskeletal nociceptive pain indeed occurs in EDS, neuropathic pain seems more common.[16] It is even possible that the pain may begin as nociceptive, but as the levels of pain increase, neuropathic pain may be a more substantial contributor. In any event, the pain can be chronic and severe. EDS must be differentiated from other genetic connective tissue syndromes such as Marfan syndrome, cutis laxa, and skeletal dysplasias.[12]

Marfan Syndrome

Marfan syndrome is an autosomal dominant connective tissue disorder with variable penetrance, resulting in many symptoms, the most dangerous of which involve the cardiovascular system.[17] The primary genetic abnormality is a mutation in the fibrillin-1 gene, the product of which coats elastins.[17]

Abnormalities of the musculoskeletal system are often the presenting physical signs of Marfan syndrome. Increased joint laxity, excessive long bone growth, scoliosis, and sternal deformities such as pectus excavatum are common.

During the physical examination, the Steinberg or “thumb sign” may indicate Marfan syndrome. The sign is positive if the entire distal phalanx of the thumb protrudes beyond the ulnar border of the hand while the thumb is abducted with the fingers curled over it. The Walker-Murdoch or “wrist” sign is evaluated by having the patient encircle the wrist proximal to the styloid process with the thumb and finger of the other hand. The sign is positive if the thumb overlaps so that it completely covers the nail of the encircling digit.[18]

Other Issues

The tendon tissue is an integral part of the concept of fascial continuity; that is, the tendon actively and passively participates in muscle performance and passive and active movements of the joints.[19][20]

In a healthy tendon, the tendon-bone portion is usually aneural. Despite this assumption, a loss of innervation of the rest of the tendon tissue could cause the presence of chronic tendinopathies, particularly in the tendon-bone area.[21]