Continuing Education Activity

Hairy cell leukemia (HCL) is a rare, chronic B-cell malignancy that involves the spleen, bone marrow, and peripheral blood. Patients often have non-specific complaints including fatigue, weakness as well as symptoms related to cytopenias. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of hairy cell leukemia and explains the role of the interprofessional team in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Outline the epidemiology of hairy cell leukemia.

Describe the pathophysiology of hairy cell leukemia.

Review the use of a bone marrow biopsy in the evaluation of hairy cell leukemia.

Describe the importance of improving care coordination among the interprofessional team members to enhance the delivery of care for patients affected by hairy cell leukemia.

Introduction

Hairy cell leukemia (HCL) is a relatively rare chronic B-cell malignancy that involves the bone marrow, spleen, and peripheral blood. The complete blood count may reveal pancytopenia including monocytopenia. Median age at diagnosis is approximately 55. Poor prognostic features, while somewhat variable in the literature, may include age, hemoglobin less than 10 g/dL, platelets less than 100, ANC less than 1000, the presence of lymphadenopathy, and massive splenomegaly. Differential diagnosis includes other B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders, including splenic marginal zone lymphoma. A distinct entity is known as hairy cell leukemia variant (HCL-V), which is biologically unique from HCL also exists. Response to typical HCL in this disease is poor. The variant can be identified by immunophenotypic differences, lack of BRAF mutation, and lack of monocytopenia.[1][2]

HCL accounts for 2% of all leukemias with approximately 1000 new cases being reported in the United States each year.

Etiology

The etiology of hairy cell leukemia is not well elucidated. However, previous exposure to various chemicals may play a role in its development. Most cases are postulated to be derived from V600E BRAF gene mutation of late activated memory B cells.

Epidemiology

Hairy cell leukemia is a rare neoplasm representing 2% of lymphoid leukemias. Median age at diagnosis is 55 years old. Although it may occur in younger individuals, it is almost never seen in children. Males are disproportionately affected compared to females, with a ratio of 4:1.

Pathophysiology

As a lymphoproliferative neoplasm, Hairy cell leukemia is a clonal disorder. The relatively recent discovery of the presence of the V600E BRAF mutation in the vast majority of cases of classic Hairy cell leukemia has suggested that the pathogenesis of this disorder lies in the RAS-RAF-MAPK signaling pathway. Constitutive activity of this pathway leads to increased cellular proliferation and survival, and, ultimately, malignancy. A recent study by Sascha Dietrich et al. also found CDKN1B inactivation in 16% of patients with classical HCL. It is the second most commonly mutated gene in HCL.

Histopathology

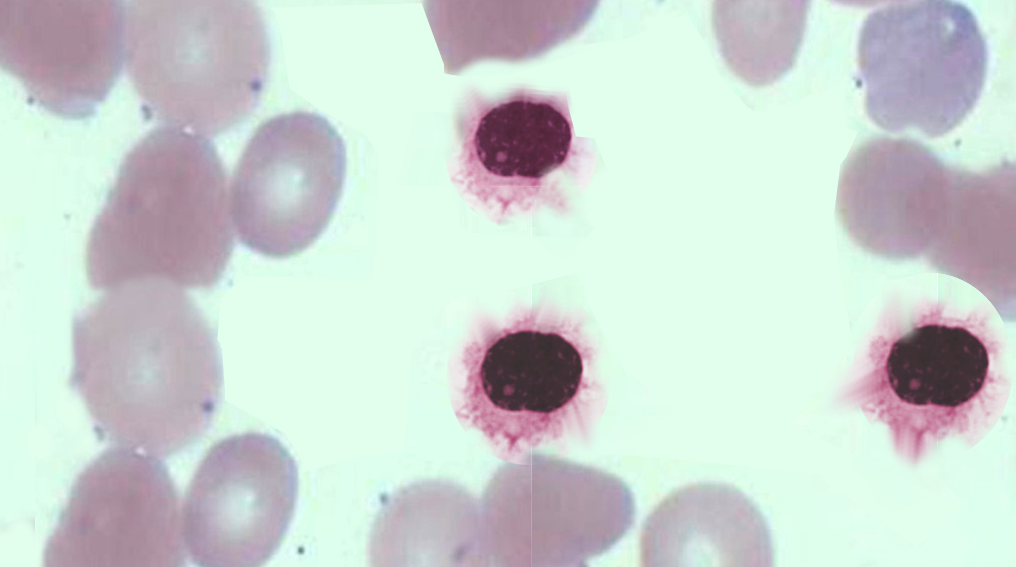

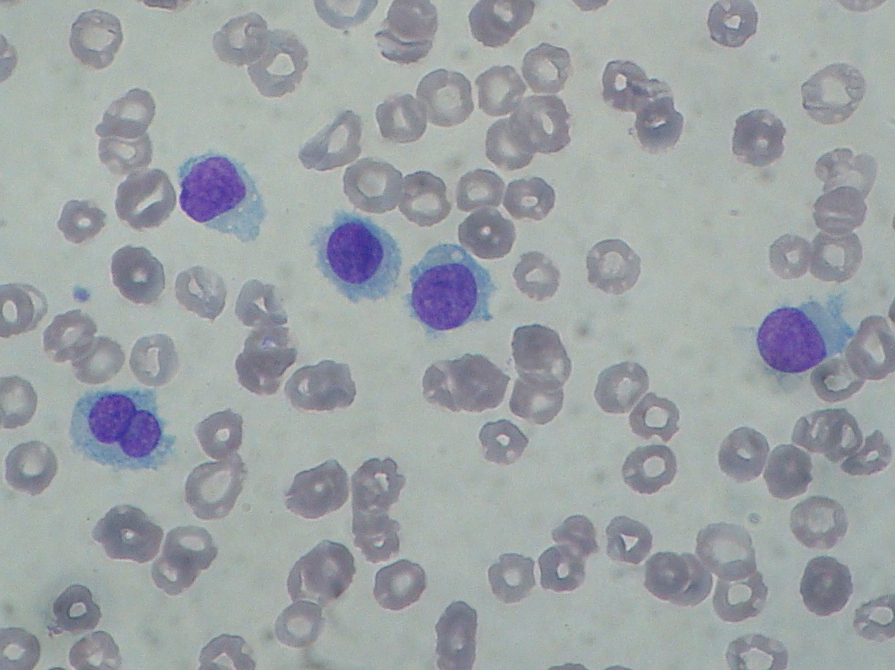

Diagnosis of HCL is based on morphological evidence of hairy cells under microscopic examination. The HCL cell is a mononuclear cell that is usually 1 to 2 times the size of a mature lymphocyte. HCL cells can be identified in Romanowsky-stained peripheral blood films from approximately 90% of patients as mononuclear cells that are usually 1 to 2 times the size of a mature lymphocyte. The nuclei are most commonly ovoid but may be round, oval, or horseshoe-shaped. The cytoplasm is variable in amount but usually abundant, pale blue to blue-gray, and occasionally described as "fluffy" or "hairy." The hairy projections are more easily visualized under the electron microscope.

History and Physical

Affected patients often have non-specific symptoms including fatigue and weakness, as well as symptoms related to cytopenias and splenomegaly. Eighty percent of patients will have significant cytopenias on presentation, with severe pancytopenia in less than 10%. While splenomegaly is a predominant feature, massive, symptomatic splenomegaly is less frequent, perhaps due to earlier detection on routine complete blood count (CBC). Autoimmune thrombocytopenia and hemolytic anemia can occur along with hairy cell leukemia, rarely. Infectious complications are common, due to both the underlying immunosuppression from cytopenias and myelosuppressive therapy.

Evaluation

Diagnosis is achieved by studies on peripheral blood, including flow cytometry and review of peripheral smear, along with bone marrow biopsy. A “dry tap,” or, inability to perform bone marrow aspiration is frequently encountered with hairy cell leukemia although not with HCL-V. The hairy cell has characteristic-appearing mononuclear cells which are typically large with circumferential hair-like cytoplasmic projections and a round, well-defined nucleus. The flow cytometry markers positive in hairy cell leukemia include CD11c, CD25, CD103, and CD123, along with typical B-cell markers such as CD19, CD20, or CD22. The cyclin-d1 expression is usually present, but it is weak or focal (in contrast to mantle cell lymphoma). HCL-V is negative for CD25 and CD123. BRAF-mutation V600E is seen in nearly all cases of classic hairy cell leukemia (although it is not present in HCL-V). CT should be considered to assess the degree of lymphadenopathy.[3][4][5]

Treatment / Management

Given its incurable nature, hairy cell leukemia treatment is reserved for symptomatic patients, including significant fatigue, symptomatic splenomegaly, and significant cytopenias (hemoglobin less than 12 g/dL, platelets, 100000/mcL, ANC less than 1000/mcL). Asymptomatic individuals should be monitored closely for disease progression with history and physical and CBC approximately every 3 to 6 months.

Cladribine and pentostatin, 2 purine analogs, are the first-line treatment for hairy cell leukemia. They are equally effective in inducing and maintaining remission. Nonetheless, cladribine is regarded as first-line chemotherapy among most hematologists due to its favorable toxicity profile. A single course of cladribine induces complete response in approximately 90% of individuals after one cycle (5 to 7 days). It is important to note that these patients will be immunosuppressed for many months following therapy, and attention to possible infectious complications is critical. A recent meta-analysis conducted by Andrasiak et al. showed that the most effective therapy in patients who are treatment-naive and in the first relapse was cladribine with rituximab maintenance. Vemurafenib was also shown to be similarly efficacious; however, it is usually used for refractory or progressive cases.

Interferon-alpha is the treatment of choice during pregnancy when treatment is warranted. It may be preferred for the initial treatment in patients with severe pancytopenia and/or active infection to improve blood counts and allow for subsequent therapy with purine analogs. However, patients with HCL who express the CD5 antigen appear to respond poorly to IFN-a.

Splenectomy may be considered in patients with symptomatic massive splenomegaly, severe pancytopenia due to splenic sequestrations and as a temporizing measure in symptomatic pregnant women.

Repeat bone marrow biopsy should be performed after treatment to confirm complete remission. Complete remission is defined as the absence of hairy cells in blood and bone marrow, resolution of splenomegaly, and recovery of peripheral blood counts (Hgb greater than 12, platelet greater than 100, ANC greater than 1500). Partial response is defined as normalization of peripheral blood counts along with a 50% decrease in splenomegaly, and less than 5% of circulating hairy cells remain. Currently, the clinical implications for minimal residual disease (MRD) are poorly defined. Many patients MRD will still have prolonged, complete hematologic remissions.

Relapsed disease can be treated with either another course of purine analog (if relapse is more than 1 year from initial treatment); however, response rates are often lower, and remissions shorter after relapse. Many other options for relapsed or refractory disease exist, including a combination of cladribine or pentostatin with rituximab, fludarabine alone or in combination with rituximab, bendamustine, and interferon-alpha. The BRAF mutation in hairy cell leukemia can be targeted by the oral BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib, which has been shown to be efficacious in both the relapsed and refractory settings.

Supportive care measures such as antimicrobial prophylaxis for viral and pneumocystis pneumonia should be considered for those with significant cytopenias. Transfused blood products, if necessary, should be irradiated to prevent transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses include:

- HCL variant: Typically has prominent nucleoli and less marrow infiltration. It is often associated with extreme leukocytosis, often without the neutropenia, monocytopenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia seen in HCL.

- Splenic diffuse red pulp small B cell lymphoma: Typically does not express annexin A1, CD25, CD103, CD123, and CD11c.

- Splenic marginal zone lymphoma: Typically does not express CD103, CD11c, and CD25.

- Other unclassifiable splenic lymphomas

- Mantle cell lymphoma: Expresses CD5 and has strong expression of cyclin D1; it does not express CD25, CD103, or annexin A1. It also does not demonstrate hairy cytoplasm in lymphocytes.

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Expresses CD5 and lacks expression of CD103. It involves both red pulp and white pulp of the spleen while HCV predominantly involves red pulp.

- Prolymphocytic leukemia: Marked the elevation of the white blood cell count, with the characteristic morphology of prolymphocytes and lack of hairy cytoplasmic projections.

Medical Oncology

Many investigational therapeutic agents are underway for the treatment of hairy cell leukemia. At least 3 monoclonal antibodies, directed against CD22, CD20, or CD25, have been evaluated in the treatment of resistant or relapsed HCL. However, except for rituximab, the anti-CD20 antibody, the other monoclonal antibodies are still considered experimental at this point.

Prognosis

The median survival is usually 4 years without treatment. VH4-34 positive HCL cases are associated with poor prognosis.

Complications

Several studies have reported cases of secondary malignancies in patients with hairy cell leukemia. It could be explained by the immunosuppression caused by the disease itself or the use of chemotherapeutic agents.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Hairy cell leukemia is a relatively rare hematological malignancy and is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes an oncologist, hematologist, internist, and an infectious disease expert. There is no cure for hairy cell leukemia and without treatment life expectancy is about 4 years. [6] (Level V)Only symptomatic patients are treated with chemotherapy. Once treated, these patients need to be followed by the oncology nurse and primary care physician with regular monitoring of blood work.

The interprofessional team can optimize the treatment of these patients through communication and coordination of care. Oncologists provide diagnoses and care plans. Nurse practitioners implement care and monitor treatment. Specialty care oncologic nurses should work with the team for coordination of care and are involved in patient education. Oncologic pharmacists should evaluate medications prescribed, recognize drug-drug interactions, provide patient education, and monitor compliance. The interprofessional team can thus improve outcomes for patients with HCL. [Level V]

Supportive care measures such as antimicrobial prophylaxis for viral and pneumocystis pneumonia should be considered for those with significant cytopenias. Patients should be educated about personal hygiene and the importance of handwashing.