Continuing Education Activity

Leishmaniasis is a protozoan disease transmitted by sandflies that is most commonly seen in Europe, Africa, Asia, and Latin America. As travel patterns shift it is a disease being more frequently introduced into developed areas. The disease may either be cutaneous or systemic. Identification of the organism and knowledge of endemic species will guide interprofessional team members toward accurate diagnosis and targeted therapy if indicated. This activity outlines the epidemiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of leishmaniasis. This review highlights the role of the interprofessional team in caring for affected patients and preparing for the potential for future cases of leishmaniasis in developed nations.

Objectives:

- Describe the epidemiology of leishmaniasis.

- Summarize the cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral leishmaniasis syndromes.

- Explain how to diagnose leishmaniasis.

- Identify the importance of improving care coordination, with particular emphasis on communication between interprofessional medical teams, to enhance prompt and thorough delivery of care to patients with leishmaniasis.

Introduction

Leishmaniasis is a disease caused by the protozoa Leishmania and is most commonly transmitted by infected sandflies. It has been historically widespread in tropical climates across multiple continents including Europe, Africa, Asia, and America. In humans, these parasites replicate intracellular and present classically with a visceral or cutaneous disease.

Leishmaniasis has tremendous historical relevance, with recorded disease thousands of years before common era (BCE).[1] An examination of ancient Egyptian and Christian Nubian mummies dating back to 3500 to 2800 BCE yielded successful amplification of Leishmaniasis donovani DNA. During a time period referred to as the Middle Kingdom, Egyptian trade and military excursions involving Nubia (modern Sudan) are thought to be responsible for the introduction of leishmaniasis into Egypt, as DNA-positive samples were not seen prior to this time period. Furthermore, some sources suspect Sudan as the original foci of visceral leishmaniasis (VL).[2] Additionally, medical manuscripts called Ebers Papyrus from 1500 BC described a cutaneous condition thought to be cutaneous leishmaniasis then termed “Nile Pimple.” With this ancient concept of disease in mind, an early form of vaccination was attempted in the Middle East and Central Asia. This was performed by taking exudates of active lesions and inoculating them into the buttocks of children.[1]

Over the next thousand years cutaneous sores consistent with leishmaniasis were described, and in historical northern Afghanistan, a disease termed the "Balkh sore" is now thought to have been caused by L. tropica. In Asia and the Middle East, the disease continued to be documented, and conditions termed the "Aleppo boil," "Jericho boil," and the "Baghdad boil." Many of these names remain relevant in modern times.

Early recognition of the infectious nature of leishmaniasis was first encountered by a Scottish physician who noticed the parasites in a Delhi boil, but it wasn’t until similar findings were seen by Russian physician Piotr Fokich Borovsky that these bodies in Asian sores were actually suspected to be protozoa as published in 1898. In 1900, a British pathologist noted ovoid bodies and suggested these represented degenerated trypanosomes. He then termed this illness “dum-dum fever.” Around the same time, Irish doctor Charles Donovan published a paper on similar ovoid bodies from the spleen of native Asian Indians. An investigation into the Indian disease kala-azar and splenic ovoid bodies described by the pathologist Leishman and clinician Donavan suggested that these ovoid bodies did not degenerate trypanosomes but a new protozoan species later termed Leishmania donovani. Over the next decades, subspecies would be identified including L. tropica, L. aethiopica, and many more. Classification of the disease into a new world and old world leishmaniasis would then be based on these organisms and their geographic distribution.[1]

Etiology

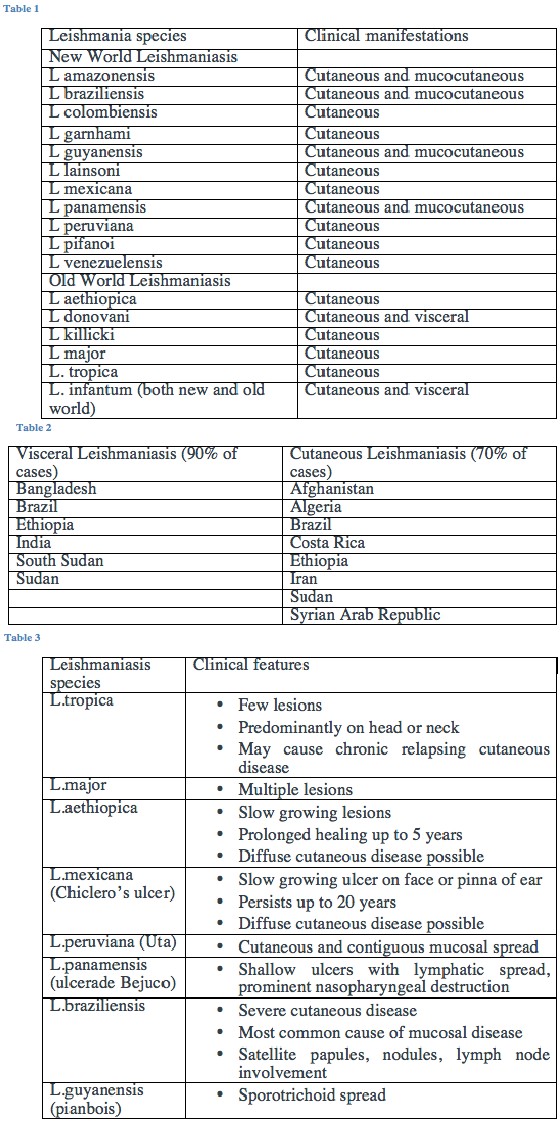

Leishmaniasis is a disease caused by a protozoa in the family Trypanosomatidae, order Kinetoplastida, genus Leishmania. The two stages of development are the amastigote and the promastigote, with the former infecting lysosomal vacuoles in phagocytic cells. The promastigote is an extracellular form that attaches to the insect microvilli. The insect vector, the sandfly, has multiple species but distinct subsets. Those that most commonly transmit Old World disease are Phlebotomus and Sergentomyia. The sandfly species notorious for spreading New World disease is Lutzomyia. A summative list of common leishmaniasis sub-species involved in New and Old World disease can be seen in table 1.[3]

Adult sandflies are very small, about one-third the size of a small mosquito or < 3.5 mm in length. They are susceptible to dehydration and therefore thrive in moist climates, hence the distribution of disease. These flies are nocturnal, and during the day are found in burrows and under rocks or other shelters. They have a characteristic “V” shape over their backs when at rest and a distinct thoracic hump that pushes the head down. While males and females both obtain carbohydrates from plant juices, females require a blood meal. It is during this meal that the vector fly transmits the protozoa to the human host.[3]

Epidemiology

Leishmaniasis is endemic to Asia, the Middle East, Northern Africa, the Mediterranean, and South and Central America. It is found in 89 countries, and worldwide 1.5 to 2 million new cases occur annually. Leishmaniasis may cause mucocutaneous or visceral disease and is attributed to 70,000 deaths per year. The World Health Organization (WHO) in 2012 reported the majority of visceral and cutaneous diseases were found in select countries.[Table 2] [1][2][4]

Pathophysiology

Leishmania parasites are transmitted by the bite of sandflies, with the genus Phlebotomus and Lutzomyia the most common vectors of Old World and New World disease, respectively.[1] As mentioned, only female sandflies require blood meals, and during these meals Leishmanis spp. are both acquired by the fly and transmitted to the host. When a disease-naive sand fly attacks an infected host, they use saw-like mouthparts inserted into the skin to create a small wound from which blood pools from injured capillaries. The infectious promastigote enters the sandfly foregut and replicates.[5][6][7] When the fly feeds on canines, rodents, marsupials, or humans it then leads to transmission of disease to the new host.[1]

Once protozoa gain access to the host, the protozoa enter the phagolysosomes. Based on which subtype of phagocytic cells are infected, Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) or visceral leishmaniasis (VL) occurs. In CL the parasites infect resident macrophages within the skin, and once each compromised cell is full of amastigotes, it bursts to allow rapid release and infection of neighboring macrophages. VL differs in that amastigotes are spread hematogenously to mononuclear cells of the liver, spleen, bone marrow, and lymph nodes of the intestine.[1]

Histopathology

Identification of parasites by histopathologic examination of fixed tissue or parasite in vitro culture is the gold standard of diagnosis. Sampling tissue from the cutaneous ulcer margin provides the highest yield fromGiemsa-stained samples from biopsies or impression smears.[8] Comparing scraping smears and fine needle aspiration cytology showed that needle aspiration improved both the detection of amastigotes and patient comfort.[9] A simplified collection method called "press-imprint-smear" has also been used, and when compared to histopathology for cutaneous disease, it had significantly higher sensitivity than histopathologic studies. This technique is performed by utilizing a 3 mm punch biopsy similar to that obtained for formalin fixed histopathology. With the press-imprint-smear, however, the tissue fragment is placed between two glass slides longitudinally (the epidermis perpendicular to the slides) and squeezed. Pressure is focused on the center of the slide and allows “juice” and tissue to spread across both slides. Next, the slides are separated, the tissue is removed, and the slides are allowed to air dry. The slides are then fixed with menthol, stained with Giemsa, and examined microscopically with an oil immersion lens.[10]

Examination of either method reveals the classic organisms as 2 to 4 mcm, round, oval bodies with characteristic nuclei and kinetoplasts.[8][10]

History and Physical

Clinical manifestations are traditionally broken up into three main syndromes: cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral.[11][4] Organisms responsible for each clinical subset are listed in Table 1. Cutaneous disease is the most common manifestation of leishmaniasis and is further subdivided into localized cutaneous and diffuse cutaneous disease. The localized cutaneous lesions often have an incubation period from 2 to 4 weeks at which time an asymptomatic papule, multiple papules, or nodules occur at the site of inoculation. These enlarge and transform into well-circumscribed ulcers with a raised violaceous border and epidermal breakdown. These lesions often heal spontaneously within 2 to 5 years (depending on the species) with a secondary depressed scar.[5][4] The characteristics of limited cutaneous lesions associated with individual subspecies are listed in Table 3.[4]

Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis also begins as a painless nodule but may progress to involve the entire cutaneous surface. It does have a predilection for face, ears, and extensor surfaces such as the knees and elbows. Invasion of the nasopharyngeal and oral mucosa may be seen in up to a third of patients. Progressive disease may result in leonine facies. Organisms most associated with diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis are L. aethiopica in Old World and L. mexicana in New World disease. Skin lesions may further progress to diffuse hypopigmented plaques and patches.

Mucosal disease is due to either hematogenous or lymphatic spread and often occurs after resolution of cutaneous lesions. The onset of mucosal manifestations usually occurs within two years but may have be delayed decades. L. braziliensis accounts for the majority of mucocutaneous disease although other organisms can be implicated (table 1). The oral and nasal mucosa is preferentially affected although ulcerative involvement may extend to vocal cords and tracheal cartilage, but bony structures are uninvolved. Mucosal disease may be severe and life-threatening.[4]

Visceral leishmaniasis is also known by the term kala-azar as initially described in India in the 1800’s.[1][11][4] With visceral involvement, there is often associated fever, splenomegaly, hypergammaglobulinemia, and pancytopenia. Often these clinical sequelae are secondary to organs directly infected including the liver, spleen, bone marrow, or other viscera. The organisms most commonly causative are L. donovani, L. infantum, and L. chagasi.[11][4] Visceral involvement, similar to the cutaneous disease, has seasonal peaks in the spring that are likely due to temperature, humidity, and vector habits.[11]

Occasionally cutaneous involvement may manifest after treatment of the visceral disease as a papular rash on the face and upper extremities. A term "post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis" has been coined to describe this, and these skin lesions are nondisfiguring and self-limited.[4]

Evaluation

As mentioned, the gold standard for diagnosis is a histopathologic examination of tissue samples. Notably, the sensitivity of examined tissue is low, and sensitivity can be increased by utilizing the press-imprint-smear method. Parasite culture tubes with Novy-MacNeal-Nicolle medium can be used but is technically difficult with low sensitivity. Micro-culture technologies have increased sensitivity up to 98.4% and are 100% specific. Serologic studies including enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, western blot, or direct agglutination are rarely used due to a poor humoral response by leishmaniasis and therefore low sensitivity. Purified antigen preparations or recombinant antigens increase the performance of these studies. Serum levels of anti-alpha-Gal IgG have been noted to be elevated in individuals infected with L. tropica and L. major. This test may be valuable as a marker of a cure for Old World CL. Intradermal skin tests have been used with good sensitivity and specificity with delayed-type hypersensitivity skin reactions equal to 5 mm is considered positive. A large disadvantage is the inability of skin testing to distinguish between prior or current infection. Polymerase chain reaction and nucleic acid amplification tests are being increasingly utilized and are both sensitive and specific.[8] Diagnosis of disease in the clinical setting often is determined by resources available.

For patients with suspected visceral disease, tissue samples may not easily be obtained, and testing with direct agglutination and rK39 dipstick testing may have more of a utility. Direct agglutination among patients with visceral/systemic involvement has a sensitivity of 97-100% and specificity of 86% to 92%. Bone marrow biopsy may be needed and is commonly positive among patients with suspected marrow involvement.[11]

Treatment / Management

For infectious disease, initial measures are often aimed at prevention. Knowledge of endemic areas, awareness of nocturnal sandfly activity, and exposure to animals in areas known to harbor disease is important. As sandflies are very small, even smaller than mosquitos, a bed net with maze patterns three times smaller than standard is required. Further impregnation with permethrin may also decrease risk. Attempts at vaccinating dogs and utilizing insecticide dog collars has also been shown to decrease disease burden.[8]

For limited CL, disease often resolves spontaneously. However dermatologic disease can be destructive, increase secondary infections, or leave permanent disabling scars. First line treatment options for the limited cutaneous disease include intralesional forms of pentavalent antimonals, including sodium stibolgluconate and meglumine antimoniate. Alternative regimens include systemic miltefosine, amphotericin B, pentamidine isethionate, paromomycine, or granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Many of these systemic agents are limited by severe adverse effects. Heat or cryotherapy are treatment options reserved for cases of < 5 cutaneous lesions.[8]

For patients with mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, systemic treatment is often required. Meglumine or stibogluconate have been first-line therapy and the WHO recommends antimonial pentavalent for a mucocutaneous disease. Treatment success rates have been as high 95% if high dosing strategies are utilized, although low dosing strategies are often used to minimize adverse effects. Azole therapies (i.e., fluconazole, ketoconazole, itraconazole) have been used in isolation and in combination with amphotericin B. Their use is limited by regional variants of the disease and resistance as well as having a minimal additive benefit to the already effective amphotericin. Agents established with good cure rates (= 90%) include amphotericin B (liposomal or colloidal dispersion), amphotericin B deoxicholate, and pentamidine. Other, less effective therapies include antimonial pentavalent and itraconazole.[12]

Visceral leishmaniasis requires treatment, and agents commonly used include antimony sodium stibogluconate, amphotericin, paromomycin, and oral miltefosine. The agent of choice is often determined by native species as resistances vary tremendously. Summatively, sodium stibogluconate is used in East Africa but has high failure rates in India. Liposomal amphotericin B is available primarily in resource-rich countries, and other formulations of amphotericin B are used in India. Paromomycin has good cure rates in India but is not as efficacious in Africa. It is used as a combination therapy in Africa with sodium stibogluconate. Pentamidine is used in South America for primary treatment and as secondary prevention of disease in patients with AIDS in Europe.[13]

Differential Diagnosis

Cutaneous ulcers in tropical regions include[4]:

- Furuncular myiasis

- Staphylococcal infection

- Lepromatous leprosy (leonine facies)

- Tuberculoid leprosy (hypopigmented patches and plaques)

- Yaws (primary stage of ulcerative or nodular lesions on lower extremities)

Prognosis

Limited cutaneous disease often is spontaneously cleared, depending on the host's innate immune system.

Mortality seen among patients with visceral disease varies when examining hospital-based populations as opposed to community-based mortality records. Overall, the WHO tentatively established a case-fatality of 10%.[14]

If treated, a cure is frequently achieved and rates are discussed above in their respective sections. Among patients with HIV, however, mortality is significantly increased as exemplified by a mortality rate of 33.6% in Ethiopian HIV-positive individuals compared with 3.6% in Ethiopian HIV-negative individuals. Despite good treatment, adverse effects of medications are common and often severe.[12][14][13]

Pearls and Other Issues

CL is the most common manifestation of leishmaniasis, and often laboratory testing is not available due to the setting in which disease occurs. CL can be suspected by the epidemiologic setting of an endemic tropical rural area. Signs and symptoms include crusted ulcerative lesions with or without satellite lesions, lymphangitic spread, or mucosal involvement.

Visceral involvement is usually manifested as fever, pallor, and weakness, or anorexia. Objective findings include splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and less commonly, leukopenia.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Leishmaniasis is a global disease, and efforts to provide education, diagnostic tools, and treatment to endemic areas is needed. Coordination through the WHO and literature from countries all over the world has provided insight into treatment, drug resistance, and transmission.

Evaluation of individual treatments has occurred worldwide. The efficacy of amphotericin in the treatment of VL is well established.[15](Level II) Miltefosine is the only oral agent approved for VL, and similar efficacy has been demonstrated in comparison with amphotericin in Asian Indian populations.[16] (Level III) Another agent frequently employed with good results is the pentavalent antimonial compound sodium stibogluconate.[17] (Level III)

Additional global epidemics including the HIV/AIDS population has been relevantly studied with one retrospective cohort showing anti-retroviral treatment significantly decreased relapse among patients with VL.[18] (Level III)