Continuing Education Activity

Pulmonary emphysema is a form of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease that is defined as a pathological, permanent dilatation of distal airways (respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and alveolar sacs) due to the destruction of airway walls without fibrotic change. Emphysema interrupts gas exchange, causing an obstructive ventilation defect. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of acute emphysema and highlights the role of interprofessional teams in caring for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify risk factors for emphysema.

- Summarize how a patient with emphysema would likely present.

- Describe how to evaluate a patient with suspected emphysema.

- Explain the role of interprofessional teams in caring for patients with emphysema.

Introduction

Pulmonary emphysema is defined as a pathological, permanent dilatation of distal airways (respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and alveolar sacs) due to the destruction of the walls of the airways without fibrotic changes. Emphysema destroys the essential ventilatory units and interrupts the gas exchange. Functionally, emphysema causes obstructive ventilatory defect evidenced in the spirometry and is included in the collective diseases of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, commonly termed as COPD. Advanced emphysema is a common and serious cause of chronic respiratory failure and acute decompensation that could be life-threatening. Due to its high morbidity and mortality,[1] recognizing and treating this condition in its early stages is vital. Emphysema is differentiated from interstitial pneumonia by the absence of fibrosis of the pulmonary interstitium. Notwithstanding, combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE) has been documented as a separate clinical entity, in many patients with proven emphysema.[2] Repeated exacerbations of emphysema and subsequent decompensation cause a rapid decline in lung function greater than expected from age.

Etiology

Though different authors around the world have speculated various causes, cigarette smoking is the most significant undisputed cause of emphysema. About 10 to 15% of cigarette smokers develop emphysema in their lifetime, and it depends on the intensity and duration of smoking. Genetic factors, including alpha-1 anti-trypsin (AAT) deficiency, an autosomal recessive disease, is a cause of emphysema, especially at a younger age, and that involves the lower lobes of the lungs predominantly. In contrast, emphysema from cigarette smoking is more common in the fifth decade and above, affecting mainly the upper lobes of the lung. Emphysema usually occurs after at least 20 pack-years of smoking.[3] Environmental exposure to certain chemicals, passive smoking, occupational exposure to substances,[4] recurrent pulmonary infections have all been reported to lead to emphysema. Exposure to smoke by traditional usage of the wood stove for cooking has been one of the most prevalent causes of emphysema, in the past, in developing countries. There have been reports of emphysema at young ages with smoking marijuana.[5]

Epidemiology

Emphysema, or the broader term COPD, which also includes chronic bronchitis, is a widely prevalent condition and has affected close to 250 million people around the world.[6] In the United States of America (USA) alone, about 14 million people suffer from this disease. The incidence of COPD is slowly increasing with a cultural increase in the use of cigarettes in the USA. The prevalence is also more in areas with higher environmental pollution. Coal workers' pneumoconiosis is another cause of emphysema, even in nonsmokers. The prevalence is slightly higher in males than females and is related to the degree of smoking.[7]

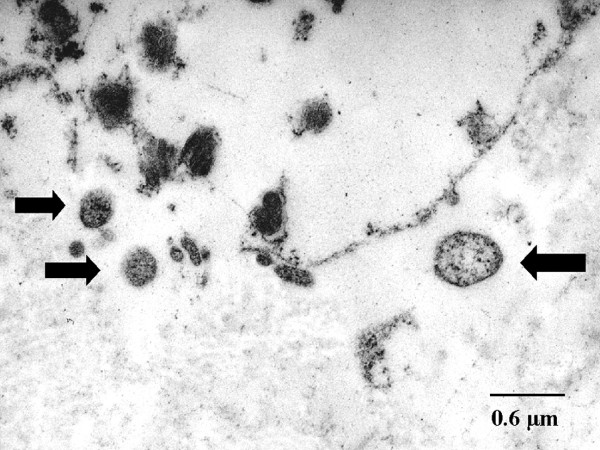

Pathophysiology

Emphysema is the destruction of the ventilatory functional respiratory unit comprising of the alveolar walls and respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, alveolar sacs. This causes permanent dilatation decreasing the surface area of the ventilatory units. Ventilation exchange necissitaes an intact alveolar wall, interstitium, and capillaries with adequate blood flow. Emphysema interrupts with gas exchange leading to extreme hypoxia and hypercapnia, thus resulting in respiratory failure. Emphysema classifies into three subtypes, namely- centriacinar, panacinar, and paraseptal. Paraseptal emphysema can occur in smokers as well as with alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency. Centriacinar is common in smokers, and panacinar is prevalent in AAT deficiency. With the exposure to smoke and other chemicals, inflammatory mediators such as macrophages, T lymphocytes, and neutrophils are activated, releasing cytokines. Also, proteinases are released, destroying the lung parenchymal connective tissue and ventilatory units causing, in advanced cases, severe hypoxia and hypercarbia. Another consequence is excessive mucus production. It is worth noting that AAT is an anti-proteinase that prevents lung destruction by counteracting the proteinase, and due to their genetic deficiency, emphysema occurs due to the loss of this protection.

History and Physical

A typical patient with emphysema would be in their fifth decade or over, with extensive smoking history presenting with a chronic, productive cough and worsening shortness of breath. In advanced COPD, the symptoms progressively worsen interfering with the activities of daily living. They may also experience unintentional weight loss and would appear cachexic. In acute exacerbations, patients decompensate and usually have a cough with a copious amount of phlegm, extensive wheezing, and progress to hypercarbia with associated hypoxic respiratory failure. Patients typically demonstrate 'purse lip breathing' and can be visibly tachypneic and use their accessory muscles of respiration. Auscultation usually reveals reduced air entry. Cor pulmonale is a complication of long-standing emphysema and could cause symptoms and signs suggestive of right heart failure. The term 'pink puffers' is used to describe these patients as they are plethoric and have hyperexpanded (barrel-shaped) chest. They are not cyanotic in milder stages. On the contrary, patients with decompensated chronic bronchitis are referred to as 'blue bloaters' as they are cyanotic. Hemoptysis is very rare in COPD, and if present, more serious conditions including malignancy should be a consideration in an appropriate clinical setting.

It is noteworthy that there is a condition called asthma COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) where both these conditions co-exist.[8] Obtaining history is very important to differentiate these two, as asthma typically has triggers for exacerbation and could have seasonal variations. Upper airway diseases like chronic rhinosinusitis can be simultaneously present and pertinent history should be obtained.

Family history is crucial as AAT deficiency is a genetically transmitted condition.[9] Often, culturally, the habit of cigarette smoking runs in the family. Likewise, information about sick contacts would be beneficial as viral infections are the most common causes of exacerbation of COPD. Vaccination history including annual influenza vaccine administration is also necessary.

Evaluation

After a good history and physical examination, the next investigation necessary for a diagnosis of COPD is a complete pulmonary function test (PFT). The PFT includes spirometry, bronchodilator reversibility testing, lung volumes, measuring carbon monoxide diffusion capacity (DLCO), and flow volume loop (FVL). In many cases, the addition of arterial blood gas (ABG) to the PFT is beneficial. The spirometry typically shows a reduction in both forced vital capacity (FVC) as well as the forced expiratory volume at first second (FEV1). The FEV1 generally declines more in proportion than the decline in FVC and the FEV1/FVC ratio is less than 0.7. However this 'obstructive' ventilatory defect is not pathognomonic to COPD and depending on other coexisting conditions, the spirometry could rarely show 'restrictive' defect as well. Significant improvement in FEV1 or FVC (defined as more than 200 ml or 12%, respectively) would indicate bronchial hyperreactivity. Obstruction is graded from mild to very severe based on the FEV1. The lung volumes could show air trapping, hyperinflation or both. The DLCO is generally reduced in COPD indicating interference with gas exchange. It is worth noting that DLCO could be reduced in other diseases including cardiac failure, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary vascular diseases, etc. The FVL has a characteristic low amplitude and prolonged expiratory phase. ABG would indicate chronic respiratory acidosis with hypoxia and assists in the management of both acute and chronic respiratory failure.

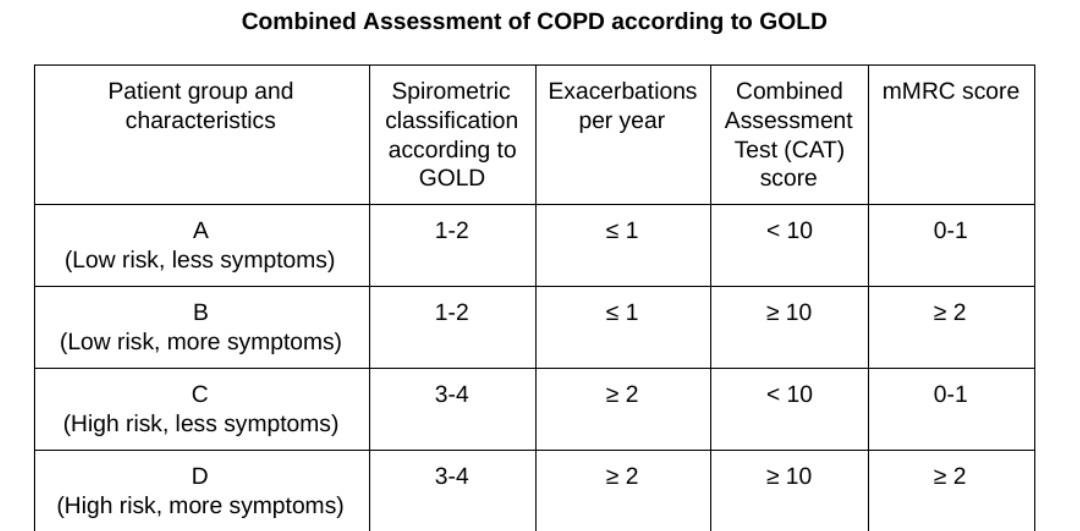

According to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Diseases (GOLD), the severity of obstruction in patients with FEV1/FVC ratio less than 0.7 grading is as follows

- Mild when FEV1 greater than or equal to 80 of predicted

- Moderate when FEV1 greater than or equal to 50 and less than 80% of predicted

- Severe when FEV1 greater than or equal to 30 and less than 50% of predicted

- Very severe when FEV1 less than 30% of predicted

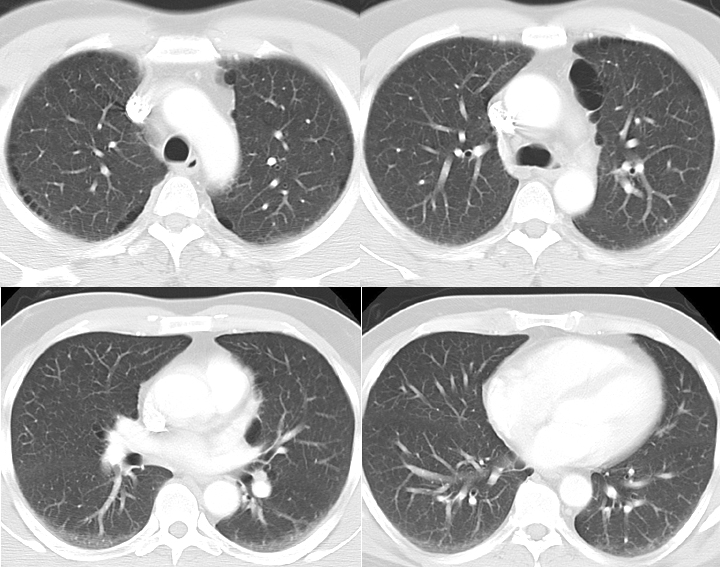

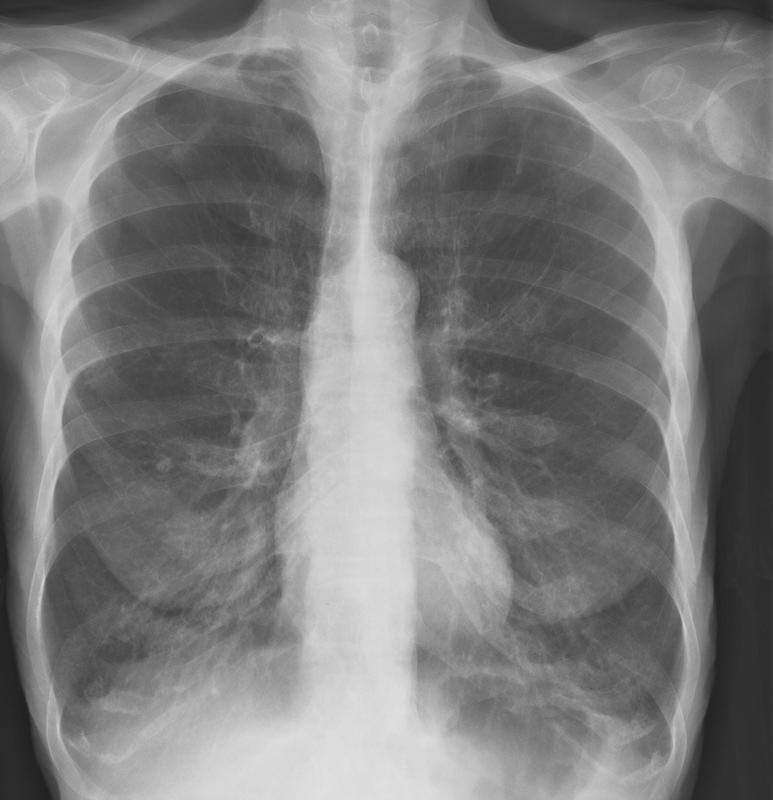

Radiology plays a significant role in diagnosing emphysema. A chest X-ray would show hyperinflation and a flattened diaphragm. Computerized tomogram (CT) of the chest is more specific and confirmatory for emphysema. Pulmonary hypertension is visible in radiological images with prominent or dilated pulmonary artery. MRI of the chest has no proven advantage over conventional CT scan of the chest in the diagnosis of emphysema.

In young patients with emphysema, genetic testing for AAT deficiency is mandatory. Coexisting asthma or pulmonary fibrosis would warrant further investigations including blood eosinophil count, immunoglobulin E levels, autoimmune, and vasculitis screen, allergy testing, etc. An echocardiogram would diagnose secondary pulmonary hypertension.

Exercise oximetry (commonly termed as the 6-minute walking test) is a simple tool to determine chronic hypoxic respiratory failure and necessary before starting long term oxygen therapy (LTOT).

The most popular staging is the one adopted by the GOLD system.[10] The GOLD system uses two tools namely the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) to determine the number of past exacerbations and the Modified Medical Research Council scale (mMRC) to determine the severity of dyspnea. There are four groups (Group A, B, C, D) determined based on the symptoms and frequency of exacerbations.

Treatment / Management

Treatment consists of both pharmacological and nonpharmacological measures. Smoking cessation is the key to preventing further lung destruction and so is the avoidance of environmental pollution. Annual influenza and appropriate pneumococcal vaccinations are a must unless contraindicated in these patients. Avoidance of sick contacts helps in the prevention of exacerbations. Adequate nutrition and, preferably, the assistance of a nutritionist can be helpful in these patients.

Long term oxygen therapy is necessary for patients who have an oxygen saturation of less than 88% or a PaO2 of less than 55 mmHg, at rest or with exertion.[11] Pulmonary rehabilitation has proven benefits in improving lung functions and exercise capacity. Monitoring the lung functions at regular intervals is beneficial to assess accelerated decline.

Pharmacological therapy is the mainstay in the management of COPD. Inhaled bronchodilators such as albuterol, levalbuterol, anticholinergics like ipratropium, inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), long-acting beta agonists (LABA) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA). Though traditionally a combination of ICS and LABA were used more, with recent evidence of increasing pneumonia in these patients, a more 'nonsteroidal' approach with the combination of LABA and LAMA have been successfully tried, of late, by many clinicians. LABA alone, without ICS or LAMA, have been approved for COPD though there has been evidence of increased deaths if used in asthma.[12] In advanced cases, triple therapy with a combination of ICS, LABA, and LAMA is necessary. Most of these medications are available in a nebulized form for people with difficulty in using the inhalers. In refractory patients, roflumilast, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, has been proven to reduce exacerbations. Many other drugs like theophylline, longterm antibiotics like azithromycin, could be tried. Though routinely not recommended, long term oral corticosteroids might be the only option in a few patients.

Systemic corticosteroids are primarily useful in COPD exacerbations along with inhaled medications. Methylprednisolone, hydrocortisone, dexamethasone are frequently used all over the world. Oral prednisone is equally effective as intravenous steroids.[13] In acute exacerbations, antibiotics and some instances, antivirals are used.

Patients with alpha-1 anti-trypsin deficiency would be candidates for "augmentation therapy" with the enzyme.

Lung volume reduction surgery is possible for selected patients with bullous emphysema. In the "end stage" disease, a lung transplant might be another option in suitable patients.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for COPD is very broad as the symptoms are nonspecific. The obstructive ventilatory defect is also present in bronchial asthma. Fixed obstruction also presents in long-standing asthma without coexisting COPD. Many chronic respiratory diseases like pulmonary fibrosis, bronchiectasis, cardiac failure, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary vascular diseases, share many common symptoms. Infectious diseases like pneumonia, tuberculosis, fungal infections; inflammatory disorders like interstitial pneumonia can all produce chronic cough. In elderly patients and those with neurological diseases, chronic aspiration should be a therapeutic option. Nonpulmonary diseases like severe acid reflux disease, upper airways diseases like chronic rhinosinusitis can be in the differential diagnosis in appropriate clinical situations.

Prognosis

Emphysema, by definition, involves permanent destruction of the alveolar walls. However, the accelerated decline of lung functions can be prevented by early diagnosis and proper treatment. Smoking cessation is the foremost factor in preventing further lung damage. Poor nutrition, the presence of bronchial hyperreactivity, male gender, bacterial colonization, coexisting immunocompromised state, cardiac or other respiratory illnesses, all carry a poor prognosis. Many clinicians use BODE index (Body mass index, Level of Obstruction, Dyspnea, Exercise capacity) as a tool to determine the possible mortality from COPD.[14] Chronic hypercarbia is an ominous sign indicating long-standing disease and is associated with poor prognosis. With every exacerbation, pulmonary function declines, more than expected for age. Presence of emphysema on CT chest is an indicator of poor prognosis. However, smoking cessation and long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) are proven to reduce mortality in COPD.

Complications

Life-threatening decompensated acute respiratory failure can occur in patients with COPD. Even in compensated patients with chronic respiratory failure, home oxygen would be needed. Continued smoking in these patients would risk the development of malignancy. Reduced exercise capacity, cachexia, cor pulmonale, recurrent chest infections are all complications of COPD. Depression, anxiety, irritability are more often features in these patients, and the treating clinician should address them accordingly.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Emphysema is an abnormal dilatation, due to destruction, of the walls of alveoli and respiratory bronchioles. It is often due to cigarette smoking.

- AAT deficiency is a genetic cause for emphysema.

- The spirometry in patients with emphysema would show the obstruction.

- Apart from smoking cessation, inhaler therapy is effective in most patients.

- LAMA can be used as a single preventive therapy along with rescue inhalers. Combination of LABA/LAMA is not inferior to LABA/ICS. In advanced cases, a combination of LABA/LAMA/ICS would be indicated. ICS alone without LABA is not recommended for the treatment of COPD.

- Lung volume reduction surgery and lung transplantation would be necessary for select patients.

- Complications include decompensated respiratory failure which can be life-threatening.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Emphysema is a chronic disorder with no cure. In addition to the coordination of care between the primary care physician and pulmonologist, often an interprofessional approach is necessary, comprising of a nutritionist, nurses, pharmacist, social worker, physical therapist and, in specific cases, a thoracic surgeon, in the management of these patients. Patient education is vital to discontinue smoking. For those who stop smoking, further lung damage is preventable, but for those who continue to smoke, the condition is debilitating and leads to poor quality of life.[15]