Introduction

Hodgkin lymphoma characteristically presents with Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells. When the cells are mononucleated, they are called Hodgkin cells. When they are multinucleated, they are called Reed-Sternberg cells.[1] The classic Reed-Sternberg cell is a large cell that can be more than 50 micrometers in diameter.[2] It is binucleated with prominent eosinophilic nuclei that are surrounded by abundant cytoplasm.[3] Reed-Sternberg cells were first illustrated incorrectly by Greenfield in a paper published in 1878. In 1898, Carl Sternberg published a paper in German that included illustrations of the cells along with the description of their pathology. However, Sternberg believed that Hodgkin disease was a form of tuberculosis. In 1902, Dorothy Reed described RS cells in her well-known paper, "On the Pathological Changes in Hodgkin Disease, with Especial Reference to it's Relation to Tuberculosis." She included a clear description of the cells, along with illustrations that she made herself. Reed emphasized that Hodgkin disease was unrelated to tuberculosis, and she used animal inoculation to prove her point. She showed that there was no immunological response to tuberculin in Hodgkin disease.[4]

Issues of Concern

Many questions surround the origin of Reed-Sternberg cells. It is particularly difficult to study these cells as they make up 1% of the tumor tissue. Reed-Sternberg cells also depend heavily on their cellular microenvironment.[5] These cells derive from cell lineages that relate to macrophages, reticulum cells, and granulocytes. There is also a hypothesis that these cells are the result of fusions between lymphocytes, reticulum cells, and lymphocytes or cells that have had viral infections. However, the majority of the evidence supports the theory that the Reed Sternberg cell originates from a B lymphocyte. Reed-Sternberg cells express CD15 and CD30.[6]

Causes

The presumption is that Reed-Sternberg cells derive from pre-apoptotic germinal center B cells. How the Reed-Sternberg cells escape apoptosis is an interesting topic. First, Reed-Sternberg cells show activity of NF-kappa B transcription factor, and when there is inhibition of the factor, there is an induction of cell death. Other cell lines show inactivating mutations in the inhibitor of NF-kappa B, I-kappa B-alpha or c-Rel amplifications. There have also been suggestions that CD30 receptor may trigger NF-kappa B activity in Reed-Sternberg cells.[7] Second, the apoptosis of germinal center B cells is under partial control of the CD95 death receptor pathway. Reed-Sternberg cell lines still express the receptor, but many cell lines are resistant to apoptosis due to CD95 cross-linking. There is also an expression of cFLIPL, which is an inhibitor of CD95 signaling. In a smaller subset, CD95 gene mutations are also responsible for CD95 inactivity. Third, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) inhibits the activation of caspase-3, which executes apoptosis. Reed-Sternberg cell lines have been shown to express XIAP.[1]

Anatomical Pathology

Reed-Sternberg cells are classically associated with Hodgkin lymphoma. However, large, atypical cells may have morphologic and immunophenotypic features resembling these cells and may pose a diagnostic challenge. Reed Sternberg-like (RS-like) cells may form neoplastic sheets, but they can also present as scattered cells. In this section, diagnostic challenges, as well as strategies that can be used to differentiate Reed-Sternberg cells from RS-like cells, will be discussed.

Reed-Sternberg-like cells found in low-grade B cell lymphomas are visible in follicular lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma or marginal zone lymphoma. In chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL), RS-like cells present amongst neoplastic cells. They resemble the immunophenotype of B cells and may also show CD20 and CD30 expression, while typically being negative for CD15. In rare cases, the RS-like cells show CD15 and CD30 expression, which makes them almost identical to Reed-Sternberg cells seen in classical Hodgkin disease. RS-like cells in CLL/SLL also show EBV positivity, which is under study as playing a role in the pathogenesis of Reed-Sternberg cells. In non-Hodgkin lymphomas, follicular lymphomas have stomal fibrosis prominently in retroperitoneal or perinephric locations. Follicular lymphoma contains neoplastic lymphoid infiltrate with small centrocytes with long nuclei, scattered centroblasts, and nucleoli. Classical Hodgkin lymphoma is associated with fibrosis as well, but the inflammatory infiltrate is made up of eosinophils, plasma cells, histiocytes, and small lymphocytes.

In follicular lymphomas, RS-like cells can present within or between neoplastic follicles. The RS-like cells have also been found to have indistinguishable immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangements to neoplastic centroblasts and centrocytes; this suggests a common origin for the cells. Reed-Sternberg-like cells in follicular lymphoma may express CD10, and this can be used to differentiate them from Reed-Sternberg cells. Reed-Sternberg-like cells may also be counted mistakingly as centroblasts, so it is essential to have adequately sized samples and use strict morphologic guidelines to arrive at the accurate diagnosis.

B-cell lineage RS-like cells are seen in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphomas and rarely in peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Reed-Sternberg-like cells express CD20, CD30, and at times, CD15. The RS-like cells are also associated with EBV infection. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphomas are diagnosable by increased vasculature. Peripheral T cell lymphomas that contain RS-like cells are very difficult to differentiate from classical Hodgkin lymphoma because of the presence of mixed inflammatory infiltrate. However, it is crucial to assess for expression of CD20, PAX-5, CD10, and BCL-6. Absence of PAX-5 presents a strong argument against the diagnosis of classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Also, if there is a morphologically and immunophenotypically abnormal lymphocytic infiltrate, this is not characteristic of classical Hodgkin lymphoma.[8]

Clinical Pathology

Neoplastic Reed-Sternberg cells comprise only 1% of the tumor mass. The majority of the infiltrate is made up of non-neoplastic T cells, B cells, eosinophils, neutrophils, macrophages, and plasma cells. The inflammatory background is vital to the clinical behavior of Reed-Sternberg cells as there is bidirectional signaling between the cells and their environment.[9]

Biochemical and Genetic Pathology

Advancements in five areas of cell biology have contributed to the understanding of Reed-Sternberg cells.

- Fixed tissue and cell line immunophenotyping have helped in the understanding of the Reed-Sternberg cell surface.

- Genotyping has given this information genetic context.

- Cell lines from Hodgkin Disease specimens have permitted the development of specific monoclonal antibodies.

- A relationship between Hodgkin and Epstein-Barr virus has hinted at a relationship between the two.

- Cytokines produced in Hodgkin Disease provide insight into the cells involved and the pathophysiology of the disease.[6]

Morphology

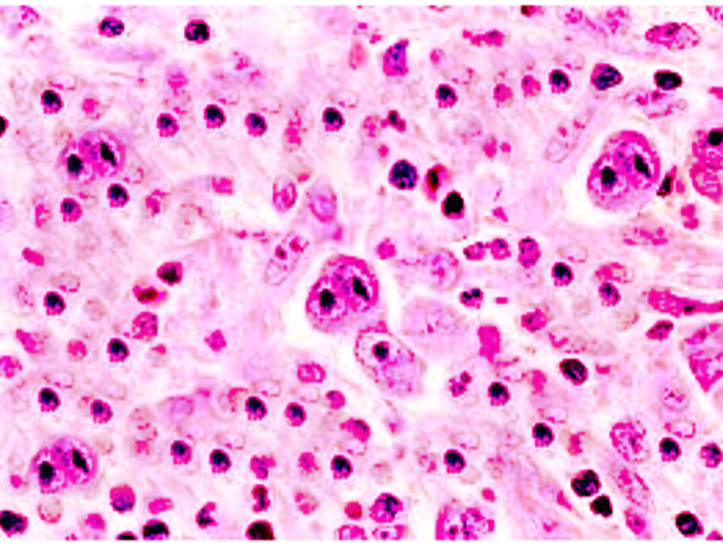

Classical diagnostic Reed-Sternberg cells are large (15 to 45 micrometers), have abundant slightly basophilic or amphophilic cytoplasm and have at least two nuclear lobes or nuclei. Diagnostic Reed-Sternberg cells must have at least two nucleoli in two separate nuclear lobes. The nuclei are large and often rounded in contour with a prominent, often irregular nuclear membrane, pale chromatin and usually one prominent eosinophilic nucleolus, with perinuclear clearing (halo), resembling a viral inclusion.[1] Please see the attached image.

Mononuclear variants of Reed-Sternberg cells are Hodgkin cells. They are characterized by a single round or oblong nucleus with large inclusion-like nucleoli.

Some Reed-Sternberg cells may have condensed cytoplasm and pyknotic reddish nuclei. These variants are known as mummified cells.

Reed-Sternberg cells surrounded by formalin retraction artifact are termed ''lacunar cells''. The latter are characteristic for nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma subtype.

Mechanisms

The first method used to isolate Reed-Sternberg cells was via suspension of fresh tissue samples. Reed-Sternberg cells were selected based on their size and negative expression of CD3, CD14, and CD20. This method did not yield consistent results and was improved upon by suspending cells onto glass slides and immunolabeling for CD30. A second technique for cell isolation used thick paraffin sections instead of fresh tissue. Enzymatic digestion and mechanical force were used to suspend cells. The suspended cells were labeled for CD30 and isolated using a hand pipette. Another technique involved usage of hydraulically driven pipettes.[10]

Clinicopathologic Correlations

Epstein Barr Virus establishes itself as a latent infection in B cells. EBV infects naive B cells that will then undergo germinal center reactions, so the virus ultimately resides in memory B cells. Once the B cells get infected, proliferation occurs. Lymphomas associated with EBV are of germinal center B cell origin. They include Hodgkin lymphoma, and about 40% of the RS cells are infected. There is an increased risk of Hodgkin lymphoma after infection with EBV. However, this association is not new. What is new is the restriction of increased risk of Hodgkin disease to EBV positive patients without increased risk demonstrated in EBV negative patients.[9]

Clinical Significance

Reed-Sternberg cells are the hallmark tumor cells of Hodgkin lymphoma. They represent less than 1% of the tumor tissue, while the majority of cells in the tissue include T cells, B cells, eosinophils, macrophages, and plasma cells [11]. It is crucial to consider RS-like cells, and their presence in tissue samples as this may present a diagnostic conundrum.

The most well known infectious disease with the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells is infectious mononucleosis due to infection with EBV. EBV infected B cells acquire the morphologic and immunophenotypic characteristics of Reed-Sternberg cells, although the mechanism of this process is still an enigma.[1]