Continuing Education Activity

Aphasia is an impairment of language function which is localized to the dominant cerebral hemisphere. Wernicke aphasia is characterized by impaired language comprehension. Despite this impaired comprehension, speech may have a normal rate, rhythm, and grammar. The most common cause of Wernicke’s aphasia is an ischemic stroke affecting the posterior temporal lobe of the dominant hemisphere. This activity outlines the evaluation and management of patients with Wernicke aphasia and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in managing patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Summarize the typical presentation of a patient with Wernicke aphasia.

- Describe the pathophysiology of Wernicke aphasia.

- Review the importance of imaging studies in making the diagnosis of Wernicke aphasia.

- Explain the importance of coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients presenting with Wernicke aphasia.

Introduction

Aphasia is an impairment of language function which is localized to the dominant cerebral hemisphere. Traditionally, aphasia is categorized as either an expressive (Broca) or a receptive (Wernicke) aphasia. Many patients have a component of both types of aphasia. This article describes Wernicke aphasia (also called receptive aphasia). This condition was first described by German physician Carl Wernicke in 1874 and is characterized by impaired language comprehension. Despite impaired comprehension, speech may have a normal rate, rhythm, and grammar. Patients with Wernicke's aphasia have impaired comprehension of their speech and thus do not recognize the errors that they are making.[1][2][3]

Etiology

The most common cause of Wernicke’s aphasia is an ischemic stroke affecting the posterior temporal lobe of the dominant hemisphere. Other causes of Wernicke’s aphasia are brain trauma, cerebral tumors, central nervous system (CNS) infections, and degenerative brain disorders. [4][5]

In most patients the cause of wernicke aphasia is an embolic stroke that afects the inferior division of the middle cerebral artery, whuch supplies the temporal cortex.

Epidemiology

Data on the incidence of Wernicke’s aphasia are limited. Annually, approximately 170,000 new cases of aphasia are related to stroke.[6]

Pathophysiology

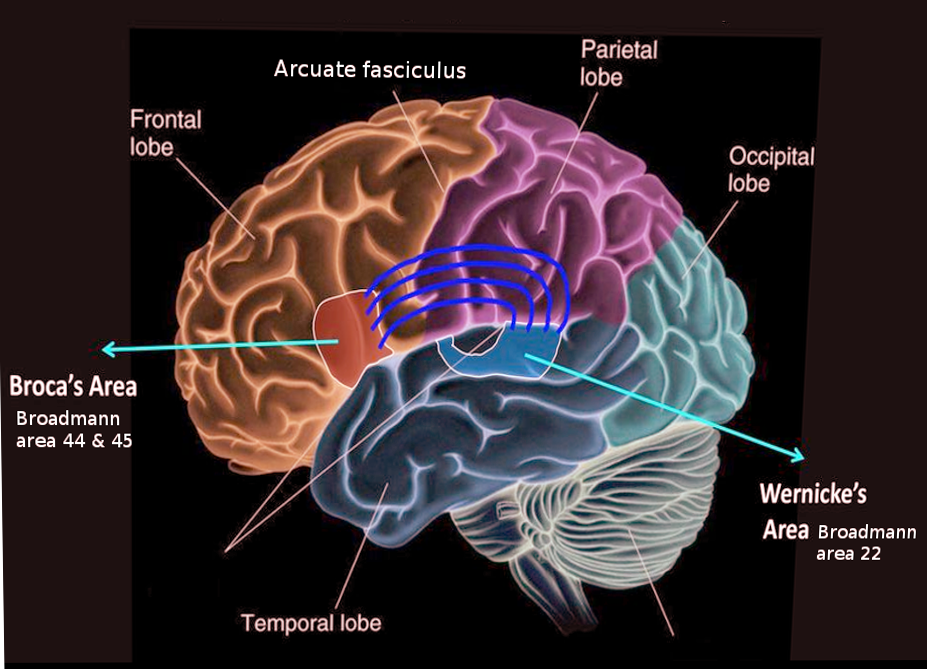

Wernicke’s area is a region in the posterior section of the superior temporal gyrus in the dominant cerebral hemisphere (Brodmann's area 22). This area closely associated with the auditory cortex. Language function localizes to the left cerebral hemisphere in almost all right-handed people and 60% of left-handed people.

History and Physical

In Wernicke's aphasia language output is fluent with a normal rate and intonation. However, the content is often difficult to understand because of paraphrastic errors. Paraphasic errors come in two forms: semantic paraphasia errors where one word is substituted for another and phenomic paraphrastic errors where one sound or syllable is substituted for another. An example of a semantic paraphasia error would be a patient saying "watch" instead of "clock." An example of a phonemic paraphasic error would be a patient saying "dock" instead of "clock." In severe cases, these errors can result in neologisms (new words) or word salad which makes communication nearly unintelligible. Because of these deficits, patients may find it easier to substitute a generic word such as "thing" or "stuff" instead of saying the word they wish to say. Reading involves the comprehension of written words, and thus reading is also often impaired in Wernicke's aphasia. As with Broca's aphasia, repetition is also impaired.

Unlike Broca's aphasia, patients with Wernicke's aphasia speak with normal fluency and prosody and follow grammatical rules with normal sentence structure. Associated neurological symptoms depend on the size and location of the lesion and include visual field deficits, trouble with the calculation (acalculia), and writing (agraphia). As opposed to Broca's aphasia, patients with Wernicke's aphasia often do not have hemiparesis accompanying the language deficit. They also do not display the same degree of emotional outbursts and depression seen with Broca's aphasia.

Repetition and naming items isusually abnormal. In some cases, there is impairment in reading. even when they are able to write fluently, the choice of words and spelling is abnormal. An early clue to Wernicke aphasia is the abnormal spelling.

In general, patients with wernicke aphasia are not aware of their deficits; in the long run they do become frustrated that others are not able to understand what they are saying. Sometimes, the patient may become aware of the errors in language if it is presented to them in an audio format.

Wernicke aphasia usually involves the posterior one third of the superior temporal gyrus. If there is involvement of the middle/inferior temporal gyri or the inferior parietal lobule, recovery is unlikely. Recovery also depends on area and size of damage, patient age and status of the contralateral cortex.

Evaluation

On the bedside examination, each component of language should be tested including assessments of verbal fluency, ability to name objects, repeating simple phrases, comprehension of simple and complex commands, reading, and writing. When testing comprehension, it is advisable to start with simple commands such as "close your eyes" or "open your mouth." Then, administer more complex commands, "show me two fingers on your left hand" and commands that require crossing the midline such as "touch your right ear with your left hand." The Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination is a widely used test to evaluate patients with language deficits. Formal neuropsychiatric testing may be necessary to determine the type and degree of the language deficit. Neuroimaging (CT, MRI, fMRI, PET, or SPECT) may be required to localized and diagnose the etiology of the aphasia.[6][7]

Wernicke's aphasia must be distinguished from Alzheimer Dementia. In both cases, patients may have trouble answering basic orientation questions. In Wernicke's aphasia, the key deficit is comprehension, whereas, with dementia, the problem is with memory. Alzheimer disease tends to be subacute in onset and progressive in nature as opposed to Wernicke's aphasia which is sudden in onset due to ischemic stroke. Neuroimaging of the brain can be helpful in distinguishing between the two conditions.

Treatment / Management

Currently, there is no standard treatment for Wernicke’s aphasia. Speech and language therapy is the mainstay of care for patients with aphasia. Because comprehension is impaired, patients may lack insight into their deficit. This makes remediation efforts very challenging. A care plan developed with a speech therapist, neuropsychologist, and neurologist would be the best way to try to optimize patient outcome. The treatment plan aims to allow the patient to better use remaining language function, improve language skill, and communicate in alternative ways so that their wants and needs can be addressed. Group therapy can give patients a chance to practice their communication skills and may lead to decreased feels of social isolation. Many commercial software vendors claim that their products will improve language function. However, these products, for the most part, have not been thoroughly vetted with rigorous clinical trials.[8][9]

Researchers are currently studying medical treatment of aphasia in randomized clinical trials. They are also developing pharmacological treatments that include drugs that affect the catecholaminergic system (bromocriptine, levodopa, amantadine, dexamphetamine), nootropic drugs such as piracetam, and medications used to treat Alzheimer Disease such as donepezil and memantine. Non-pharmacological approaches include transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct stimulation. Trials to date have been small with mixed results. Further studies are needed to determine the effectiveness of these approaches.

When the cause of Wernicke’s aphasia is a stroke, recovery of language function peaks within two to six months, after which time further progress is limited. However, efforts should be made to try to improve communication, since an improvement in aphasia has been documented long after a stroke. Family support and social support are essential to a good outcome. Treatment of post-stroke depression and post-stroke cognitive issues, as well as remediation of other neurological disorders such as neglect, agnosia, and hemiparesis, should be addressed during rehabilitation to optimize patient outcome.

Differential Diagnosis

- Cancer

- Cardioembolic stroke

- Alzheimer disease

- Frontal lobe syndromes

- Head trauma

- Seizure

Pearls and Other Issues

When communicating with patients with Wernicke's aphasia, it is important to eliminate background noise and distractions, maintain eye contact, and keep voice at a normal volume and rate. Ideally, sentences should be short, and one should avoid asking questions that require a lengthy explanation. Yes or no questions are often preferable. Patients may prefer to write their answers, so it is advisable to keep a notepad and pen available.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with Wernicke's aphasia are often difficult to diagnose. Often they generate many words in grammatically correct sentences with a normal rate, but what they say does not make sense. They use way too many irrelevant words and fail to realize that they have a speech problem. These patients may first come to attention during admission for another problem and it is important for healthcare workers to be aware of this speech problem. While there is no specific therapy, recent studies suggest that a focus on communication and functional therapy may help some people. The prognosis is strongly dependent on the primary condition causing Wernicke's aphasia. In addition, the patient's age, level of education, motivation, and gender also play a role in recovery. The length of therapy can be for months or years but not everyone has a positive outcome. [10][11]