[1]

Rosenfeld RM, Piccirillo JF, Chandrasekhar SS, Brook I, Ashok Kumar K, Kramper M, Orlandi RR, Palmer JN, Patel ZM, Peters A, Walsh SA, Corrigan MD. Clinical practice guideline (update): adult sinusitis. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2015 Apr:152(2 Suppl):S1-S39. doi: 10.1177/0194599815572097. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25832968]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[2]

Meltzer EO, Hamilos DL, Hadley JA, Lanza DC, Marple BF, Nicklas RA, Bachert C, Baraniuk J, Baroody FM, Benninger MS, Brook I, Chowdhury BA, Druce HM, Durham S, Ferguson B, Gwaltney JM, Kaliner M, Kennedy DW, Lund V, Naclerio R, Pawankar R, Piccirillo JF, Rohane P, Simon R, Slavin RG, Togias A, Wald ER, Zinreich SJ, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI), American Academy of Otolaryngic Allergy (AAOA), American Academy of Otolaryngology--Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS), American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI), American Rhinologic Society (ARS). Rhinosinusitis: establishing definitions for clinical research and patient care. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2004 Dec:114(6 Suppl):155-212

[PubMed PMID: 15577865]

[3]

Meltzer EO, Hamilos DL, Hadley JA, Lanza DC, Marple BF, Nicklas RA, Bachert C, Baraniuk J, Baroody FM, Benninger MS, Brook I, Chowdhury BA, Druce HM, Durham S, Ferguson B, Gwaltney JM Jr, Kaliner M, Kennedy DW, Lund V, Naclerio R, Pawankar R, Piccirillo JF, Rohane P, Simon R, Slavin RG, Togias A, Wald ER, Zinreich SJ, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, American Academy of Otolaryngic Allergy, American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, American Rhinologic Society. Rhinosinusitis: Establishing definitions for clinical research and patient care. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2004 Dec:131(6 Suppl):S1-62

[PubMed PMID: 15577816]

[4]

Anon JB, Jacobs MR, Poole MD, Ambrose PG, Benninger MS, Hadley JA, Craig WA, Sinus And Allergy Health Partnership. Antimicrobial treatment guidelines for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2004 Jan:130(1 Suppl):1-45

[PubMed PMID: 14726904]

[5]

Papadopoulou AM, Chrysikos D, Samolis A, Tsakotos G, Troupis T. Anatomical Variations of the Nasal Cavities and Paranasal Sinuses: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2021 Jan 15:13(1):e12727. doi: 10.7759/cureus.12727. Epub 2021 Jan 15

[PubMed PMID: 33614330]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[6]

Jorissen M, Hermans R, Bertrand B, Eloy P. Anatomical variations and sinusitis. Acta oto-rhino-laryngologica Belgica. 1997:51(4):219-26

[PubMed PMID: 9444370]

[7]

Benninger MS. The impact of cigarette smoking and environmental tobacco smoke on nasal and sinus disease: a review of the literature. American journal of rhinology. 1999 Nov-Dec:13(6):435-8

[PubMed PMID: 10631398]

[8]

Frieri M, Kumar K, Boutin A. Review: Immunology of sinusitis, trauma, asthma, and sepsis. Allergy & rhinology (Providence, R.I.). 2015 Jan:6(3):205-14. doi: 10.2500/ar.2015.6.0140. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26686215]

[9]

Saltagi MZ, Comer BT, Hughes S, Ting JY, Higgins TS. Management of Recurrent Acute Rhinosinusitis: A Systematic Review. American journal of rhinology & allergy. 2021 Nov:35(6):902-909. doi: 10.1177/1945892421994999. Epub 2021 Feb 23

[PubMed PMID: 33622038]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[10]

Aring AM, Chan MM. Current Concepts in Adult Acute Rhinosinusitis. American family physician. 2016 Jul 15:94(2):97-105

[PubMed PMID: 27419326]

[11]

Bhattacharyya N, Grebner J, Martinson NG. Recurrent acute rhinosinusitis: epidemiology and health care cost burden. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2012 Feb:146(2):307-12. doi: 10.1177/0194599811426089. Epub 2011 Oct 25

[PubMed PMID: 22027867]

[13]

Beule AG. Physiology and pathophysiology of respiratory mucosa of the nose and the paranasal sinuses. GMS current topics in otorhinolaryngology, head and neck surgery. 2010:9():Doc07. doi: 10.3205/cto000071. Epub 2011 Apr 27

[PubMed PMID: 22073111]

[14]

Karunasagar A, Garag SS, Appannavar SB, Kulkarni RD, Naik AS. Bacterial Biofilms in Chronic Rhinosinusitis and Their Implications for Clinical Management. Indian journal of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery : official publication of the Association of Otolaryngologists of India. 2018 Mar:70(1):43-48. doi: 10.1007/s12070-017-1208-0. Epub 2017 Sep 25

[PubMed PMID: 29456942]

[15]

Vestby LK, Grønseth T, Simm R, Nesse LL. Bacterial Biofilm and its Role in the Pathogenesis of Disease. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland). 2020 Feb 3:9(2):. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9020059. Epub 2020 Feb 3

[PubMed PMID: 32028684]

[16]

Chang YS, Chen PL, Hung JH, Chen HY, Lai CC, Ou CY, Chang CM, Wang CK, Cheng HC, Tseng SH. Orbital complications of paranasal sinusitis in Taiwan, 1988 through 2015: Acute ophthalmological manifestations, diagnosis, and management. PloS one. 2017:12(10):e0184477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184477. Epub 2017 Oct 3

[PubMed PMID: 28972988]

[17]

Rosenfeld RM, Piccirillo JF, Chandrasekhar SS, Brook I, Kumar KA, Kramper M, Orlandi RR, Palmer JN, Patel ZM, Peters A, Walsh SA, Corrigan MD. Clinical practice guideline (update): Adult Sinusitis Executive Summary. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2015 Apr:152(4):598-609. doi: 10.1177/0194599815574247. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25833927]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[18]

Meltzer EO, Hamilos DL. Rhinosinusitis diagnosis and management for the clinician: a synopsis of recent consensus guidelines. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2011 May:86(5):427-43. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0392. Epub 2011 Apr 13

[PubMed PMID: 21490181]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[19]

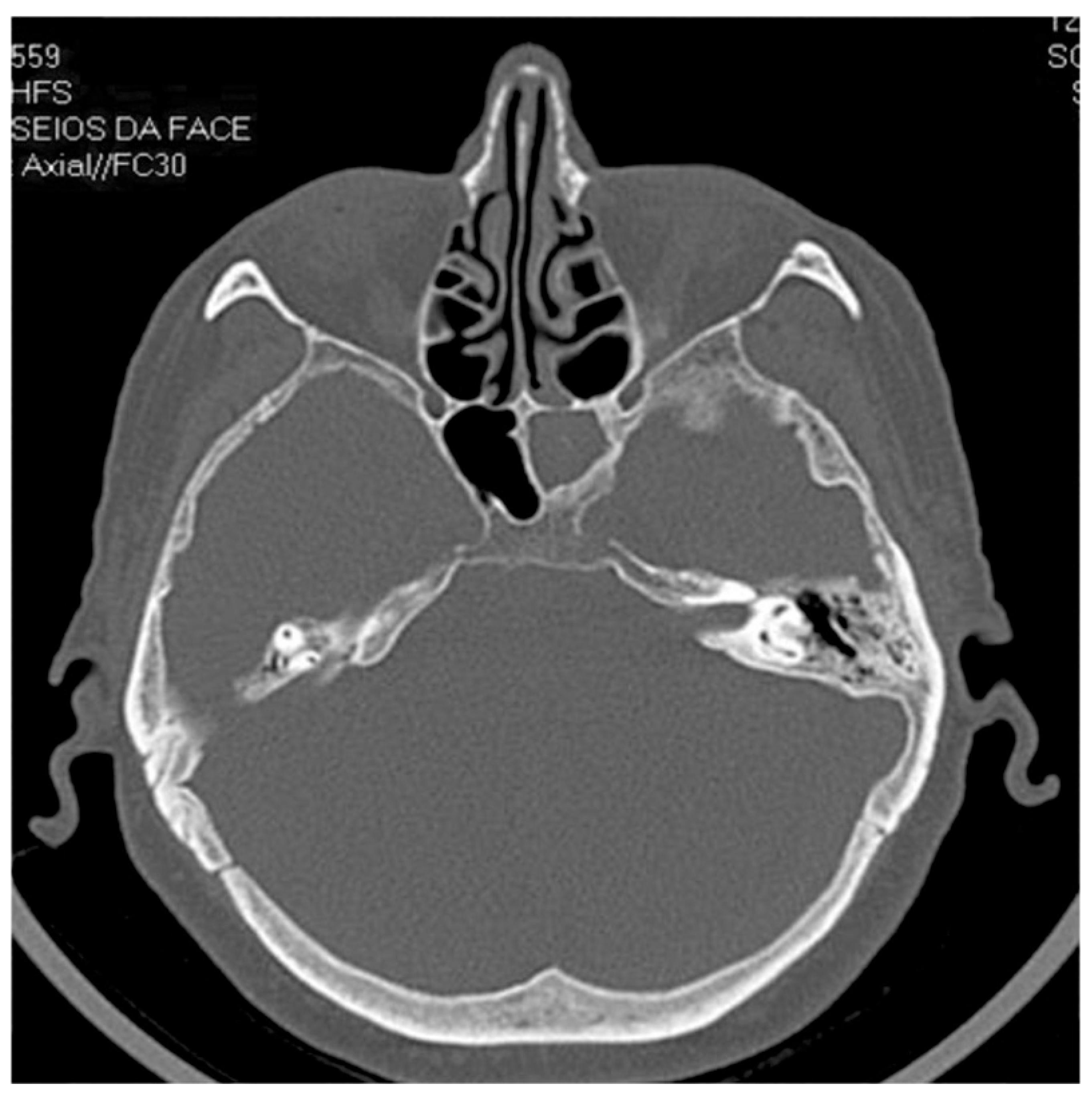

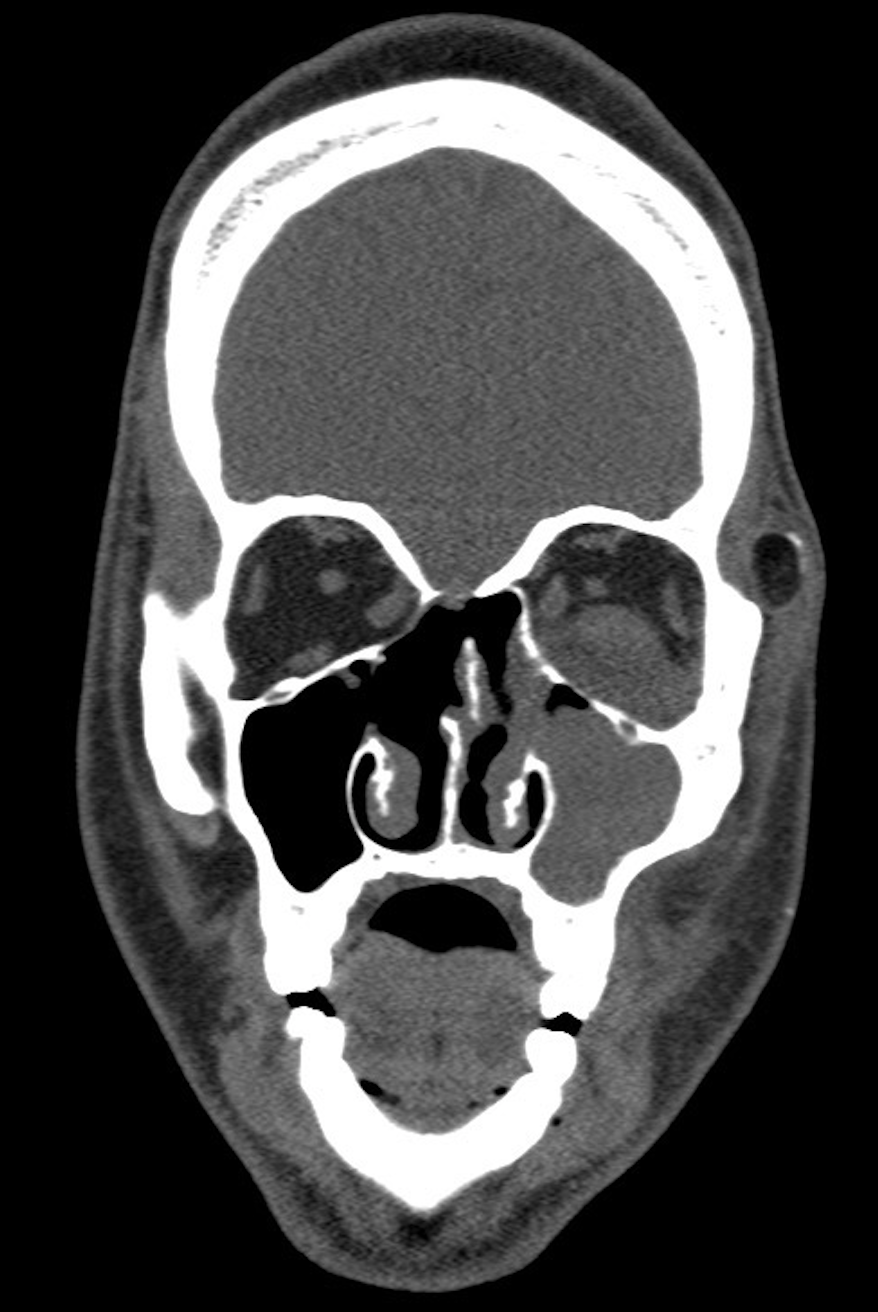

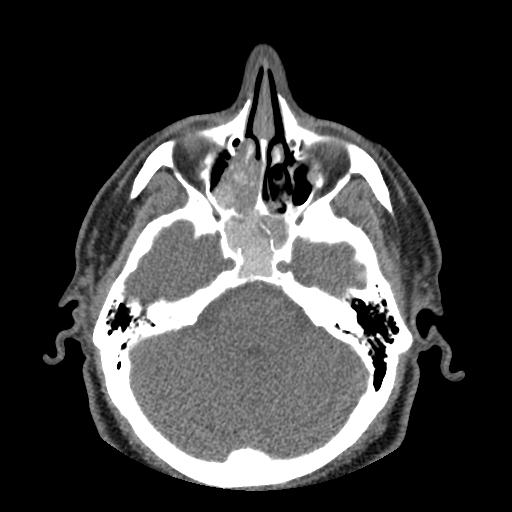

Cashman EC, Macmahon PJ, Smyth D. Computed tomography scans of paranasal sinuses before functional endoscopic sinus surgery. World journal of radiology. 2011 Aug 28:3(8):199-204. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v3.i8.199. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 22022638]

[20]

Kanjanawasee D, Seresirikachorn K, Chitsuthipakorn W, Snidvongs K. Hypertonic Saline Versus Isotonic Saline Nasal Irrigation: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. American journal of rhinology & allergy. 2018 Jul:32(4):269-279. doi: 10.1177/1945892418773566. Epub 2018 May 18

[PubMed PMID: 29774747]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[21]

Park DY, Choi JH, Kim DK, Jung YG, Mun SJ, Min HJ, Park SK, Shin JM, Yang HC, Hong SN, Mo JH. Clinical Practice Guideline: Nasal Irrigation for Chronic Rhinosinusitis in Adults. Clinical and experimental otorhinolaryngology. 2022 Feb:15(1):5-23. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2021.00654. Epub 2022 Feb 15

[PubMed PMID: 35158420]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[22]

Mortuaire G, de Gabory L, François M, Massé G, Bloch F, Brion N, Jankowski R, Serrano E. Rebound congestion and rhinitis medicamentosa: nasal decongestants in clinical practice. Critical review of the literature by a medical panel. European annals of otorhinolaryngology, head and neck diseases. 2013 Jun:130(3):137-44. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2012.09.005. Epub 2013 Feb 1

[PubMed PMID: 23375990]

[23]

Rovelsky SA, Remington RE, Nevers M, Pontefract B, Hersh AL, Samore M, Madaras-Kelly K. Comparative effectiveness of amoxicillin versus amoxicillin-clavulanate among adults with acute sinusitis in emergency department and urgent care settings. Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians open. 2021 Jun:2(3):e12465. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12465. Epub 2021 Jun 16

[PubMed PMID: 34179886]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[24]

Lee S, Yen MT. Management of preseptal and orbital cellulitis. Saudi journal of ophthalmology : official journal of the Saudi Ophthalmological Society. 2011 Jan:25(1):21-9. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2010.10.004. Epub 2010 Dec 10

[PubMed PMID: 23960899]

[25]

Seresirikachorn K, Khattiyawittayakun L, Chitsuthipakorn W, Snidvongs K. Antihistamines for treating rhinosinusitis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled studies. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2018 Feb:132(2):105-110. doi: 10.1017/S002221511700192X. Epub 2017 Sep 13

[PubMed PMID: 28901282]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[26]

Venekamp RP, Thompson MJ, Hayward G, Heneghan CJ, Del Mar CB, Perera R, Glasziou PP, Rovers MM. Systemic corticosteroids for acute sinusitis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014 Mar 25:(3):CD008115. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008115.pub3. Epub 2014 Mar 25

[PubMed PMID: 24664368]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[27]

Parnes SM. The role of leukotriene inhibitors in patients with paranasal sinus disease. Current opinion in otolaryngology & head and neck surgery. 2003 Jun:11(3):184-91

[PubMed PMID: 12923360]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[28]

Sikand A, Ehmer DR Jr, Stolovitzky JP, McDuffie CM, Mehendale N, Albritton FD 4th. In-office balloon sinus dilation versus medical therapy for recurrent acute rhinosinusitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. International forum of allergy & rhinology. 2019 Feb:9(2):140-148. doi: 10.1002/alr.22248. Epub 2018 Nov 19

[PubMed PMID: 30452127]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[29]

Costa ML, Psaltis AJ, Nayak JV, Hwang PH. Medical therapy vs surgery for recurrent acute rhinosinusitis. International forum of allergy & rhinology. 2015 Aug:5(8):667-73. doi: 10.1002/alr.21533. Epub 2015 May 7

[PubMed PMID: 25950995]

[30]

Galletti B, Gazia F, Freni F, Sireci F, Galletti F. Endoscopic sinus surgery with and without computer assisted navigation: A retrospective study. Auris, nasus, larynx. 2019 Aug:46(4):520-525. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2018.11.004. Epub 2018 Dec 6

[PubMed PMID: 30528105]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[31]

Kacker A, Tabaee A, Anand V. Computer-assisted surgical navigation in revision endoscopic sinus surgery. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2005 Jun:38(3):473-82, vi

[PubMed PMID: 15907896]