Introduction

The nasopharynx represents the most superior portion of the pharynx, bounded superiorly by the skull base and inferiorly by the soft palate. The nasopharynx connects the nasal cavity to the oropharynx and contains the Eustachian tube openings and adenoids. Notable clinical situations include nasopharyngeal carcinoma and adenoidal hypertrophy. This review will discuss the anatomy of the nasopharynx, including the structure, function, embryology, blood supply, innervation, anatomical variants, and clinical relevance.

Structure and Function

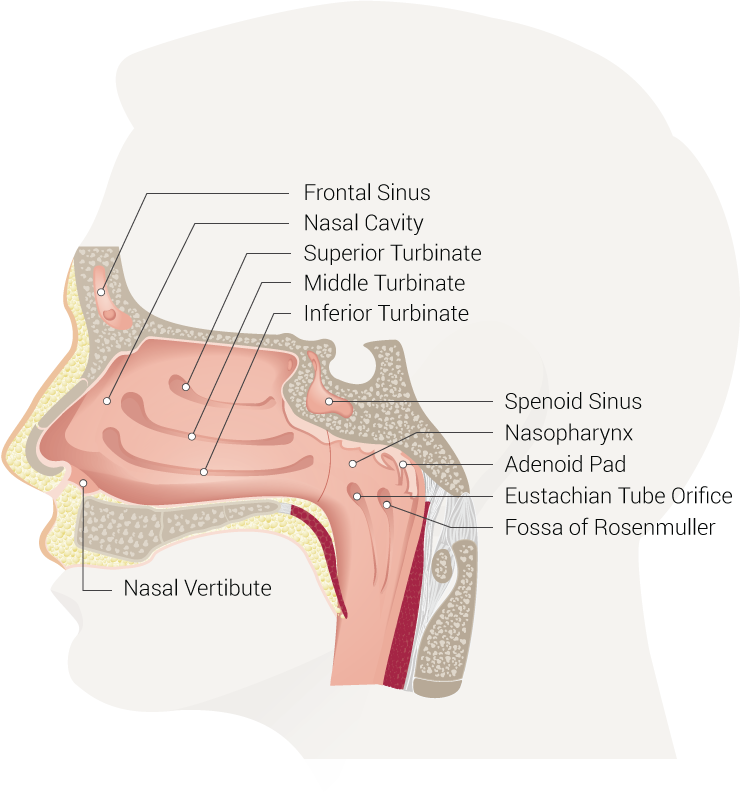

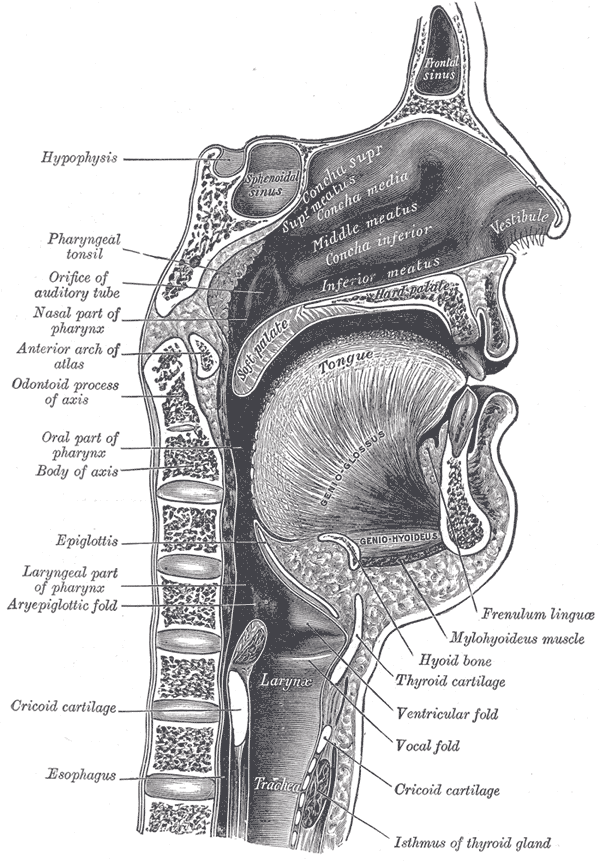

Boundaries of the nasopharynx[1][2]:

- Superiorly: the skull base.

- Anteriorly: the nasal cavity.

- Posteriorly: posterior pharyngeal wall.

- Inferiorly: the soft palate.

- Laterally: the medial pterygoid plates and superior pharyngeal constrictor muscles (surrounded by visceral fascia)

Shape and Size[2]:

The anterior-posterior (A-P) diameter of the nasopharynx is approximately 2 cm, and the height is approximately 4 cm.

Contents[1][2][3]:

- The eustachian tube opening is located at the posterolateral wall.

- The torus tubarius is located immediately posterior to the opening of the eustachian tube.

- The fossa of Rosenmuller is located superior and posteriorly to the torus tubarius.

- The adenoids (nasopharyngeal tonsils) are located in the roof and posterior wall of the nasopharynx.

Function[4][2][5][6]:

- The nasopharynx is a component of the upper airway system, connecting the nasal passages to the larynx and trachea, via the oropharynx.

- Muscles intrinsic to the nasopharynx control the opening of the eustachian tubes, which help control ventilation and equilibrium of atmospheric pressure between the middle ear cavity and nasopharynx.

- The nasopharynx contributes to voice resonance and production. Obstruction of the nasopharynx leads to voice changes (hyponasal).

- As inspired air is filtered and humidified within the nasal cavity, dust particles are trapped in nasal mucus and transported via the “mucociliary elevator,” which beats towards the nasopharynx. From there, nasal debris drains to the oropharynx.

- The nasopharyngeal isthmus blocks the nasopharynx during swallowing.

Embryology

As the name suggests, scientists believe that the nasopharynx derives from both the nasal cavity and the pharynx embryologically. Both the eustachian tube and its opening develop from the first pharyngeal arch. Therefore, posterior to the eustachian tube opening appears to be an embryological extension of the pharynx. Anterior to the eustachian tube opening is considered an extension of the nasal cavity via the primitive nasal sac. This theory has support from histological evidence that nasopharyngeal mucosa anterior to the eustachian tube opening resembles that of the nasal cavity (highly vascular and dense with lymphoid tissue) and posterior mucosa resembles that of the oropharynx (stratified squamous).[7]

The nasopharyngeal area derives from the neural crests of the ectodermal leaflet.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Vascular supply to the nasopharynx is provided by branches of the internal carotid artery (mandibular artery), maxillary artery (pterygopalatine artery), facial artery (ascending palatine artery), and ascending pharyngeal artery (superior pharyngeal artery). Venous drainage is via the parapharyngeal venous plexus. The plexus drains into the retropharyngeal and facial veins, which both drain to the internal jugular vein.[8][1]

Lymphatic drainage of the nasopharynx is particularly clinically relevant for patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. The initial lymph collecting system is a capillary network within the mucosal membrane, which is connected to a similar network within the nasal atrium, turbinates, and posterior floor. From there, the first-tier lymph nodes are the retropharyngeal, referred to as the Rouvière nodes. The retropharyngeal nodes lead to the internal jugular nodes.[9][1]

Nerves

Sensory innervation anterior to the eustachian tube opening is via the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve (CN V2), which travels through the sphenopalatine ganglion. The glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX) provides posterior sensory innervation. Muscles originating in the nasopharynx receive their motor supply from the vagus nerve (CN X), except for the tensor veli palatini muscle, which is supplied by the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve (CN V3).[7][10][6]

Muscles

The primary muscles associated with the nasopharynx are the tensor veli palatini, levator veli palatini, and the salpingopharyngeus, which all originate from the eustachian tube opening. The tensor veli palatini tenses the soft palate, and the levator veli palatini elevates the soft palate, which helps seal off the nasopharynx from the oropharynx during swallowing. The salpingopharyngeus also aids with swallowing by elevating the pharynx. Additionally, all three of these muscles open the eustachian tube orifice during swallowing, which helps equilibrate atmospheric pressure between the middle ear cavity and the nasopharynx.[2][6]

Physiologic Variants

The dimensions of the nasopharynx (height and A-P diameter) vary significantly between individuals. Additionally, asymmetry of the superficial landmarks, such as the eustachian tube openings, describes the major physiologic (anatomic) variants of the nasopharynx. When asymmetry is observed on endoscopic or radiologic imaging, infiltrating tumors or mucosal masses versus benign anatomic variants should merit consideration. Lateral recesses, such as the fossa of Rosenmuller, become more visible with aging, which appears to be a consequence of physiologic degeneration of submucosal lymphoid tissue (adenoids).[11]

Surgical Considerations

Adenoidectomy

Adenoidectomy, the removal of adenoid tissue, is amongst the most common surgeries performed by an otolaryngologist. The adenoids (nasopharyngeal tonsils) are within the roof and posterior wall of the nasopharynx. Nasopharyngeal adenoid hypertrophy (NAH) is a common cause of nasal obstruction and sleep-disordered breathing (SDB)/obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in children, and it is associated with recurrent otitis media and chronic rhinosinusitis. There are three primary indications for an adenoidectomy: chronic otitis media with effusion and concomitant eustachian tube dysfunction, recurrent rhinosinusitis refractory to standard medical treatment, and accompanying tonsillectomy for management of SDB/OSA. Adenoid tissue can regenerate post-removal but rarely to the extent to reproduce pre-operative symptoms.[12][3][13]

The traditional method of removing adenoid tissue is using the “blind curettage” method. With this method, the adenoid tissue is not directly visible; therefore, there is a theoretical risk of leaving residual tissue. Consequently, endoscopic techniques have been developed to help achieve full visualization. The most popular endoscopic techniques use a “microdebrider” or radiofrequency.[14]

Clinical Significance

Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a malignant epithelial tumor that most commonly originates from the fossa of Rosenmuller. Southern Chinese males (40 to 60 years old) have the highest incidence. Predisposing factors appear to be host genetics (HLA gene on chromosome 6p21), environmental factors (i.e., chemicals or carcinogens), and Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) infection. Due to the association with EBV, antibody titers are useful diagnostic markers. The size of the tumor is the crucial prognostic factor, and radiation therapy is the treatment of choice.[1][15]

Regarding nodal metastasis, cervical lymphadenopathy is the most common presenting symptom (75% of cases). Typically, the retropharyngeal nodes are the first to be involved; however, in 35% of cases, the retropharyngeal nodes are bypassed, and the internal jugular nodes are the first to be involved. Nodal metastasis exhibits an inferior spread pattern; thus, superior nodes will be larger than inferior nodes. Distant metastasis appears to occur at higher rates in NPC in comparison to other head and neck cancers (5 to 41% vs. 5 to 24%). Bone and lungs are the most common sites of distant metastasis.[1]

A nonspecific symptom of NPC is a headache; however, NPCs can spread to adjacent structures. Therefore, presenting signs and symptoms typically depend on which structures are involved. If the tumor involves the eustachian tube opening, the patient can present with serous otitis media, typically unilateral. Tumors can spread anteriorly through the sphenopalatine foramen and then the pterygopalatine fossa. From there, malignant cells can spread centrally along the CN V3 to enter the cranium. Lateral spread to the parapharyngeal space also puts CN V3 at risk, and denervation atrophy of the mastication muscles are visible on MRI in these scenarios. Trismus, also known as “lockjaw,” is a common presenting symptom if the medial or lateral pterygoid muscles are affected. Posterolateral spread into the carotid space puts CNs IX, X, XI, XII at risk; thus, symptoms associated with these nerves can be present. Posterior spread through the posterior pharyngeal wall and retropharyngeal space can infiltrate the prevertebral muscles. The involvement of the vertebral bodies and spinal cord occurs in late stages. Inferior spread into the oropharynx is most easily observable with MRI. Superior spread can lead to cranial involvement via the foramen lacerum, foramen ovale, or direct skull-base erosion. Spread in every direction can result in cavernous sinus involvement, which may present with CN III, IV, V1, and VI injuries.[1]

Nasopharyngeal Adenoid Hypertrophy

The adenoids, also known as the nasopharyngeal tonsils, are located in the roof and posterior wall of the nasopharynx and contribute to Waldeyer’s ring of lymphoid tissue. Normally, the adenoids undergo physiological hypertrophy at 6-10 years of age. Nasopharyngeal adenoid hypertrophy (NAH) refers to non-physiologic enlargement, typically benign, and it is the most common cause of nasal obstruction in children. The etiology of NAH is unknown, but persistent rhinitis may be a risk factor. Patients commonly present with open-mouth breathing, snoring, rhinorrhea, and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Treatment of choice is an adenoidectomy.[16][17][12]

NAH is not common in adulthood since the adenoids naturally regress, starting at approximately age 16. Theoretical etiologies of adult NAH may be persistent NAH from childhood, re-proliferation in response to infection, or a response to an infection in an immunocompromised state.[12]

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), formerly called Wegner’s granulomatosis, is an idiopathic small-to-medium-sized vessel vasculitis. Classically, GPA involves the nasopharynx, lungs, and kidneys. In 80% of patients, the initial presenting symptoms involve the nasopharynx, which can include uncomplicated sinusitis, nosebleeds, and damage to the bony walls of the sinus. When a patient is only presenting with nasopharyngeal symptoms, it is referred to as “limited GPA,” and 46 to 70% of these patients are positive for c-ANCA. Mainstay treatment is immunosuppression with cyclophosphamide and corticosteroids, and up to 90% of patients improve with this regiment. Rituximab is also available for refractory cases.[18]

Nasopharyngeal Cyst

Nasopharyngeal cysts are rare and usually present asymptomatically; therefore, most are diagnosed incidentally on imaging or routine nasal endoscopy. However, these cysts may present with cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea, purulent rhinorrhea, nasal obstruction, headache, and middle ear effusion. CSF rhinorrhea is associated with a congenital defect of the craniopharyngeal canal. Normally, this canal degenerates in the 6th week of gestation after the formation of the anterior pituitary gland from Rathke’s pouch. If the craniopharyngeal canal remains patent (0.42% of the asymptomatic population), ventral nasopharyngeal cysts may form and lead to CSF rhinorrhea. Treatment for symptomatic cysts is surgical resection.[19]

Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA) is a benign, vascular tumor that typically occurs in young males 9-19 years of age. JNAs are rare, representing 0.05% of all head and neck tumors. Common symptoms include nasal obstruction and epistaxis, and treatment of choice is surgical resection with preoperative embolization. Without treatment, aggressive JNAs can spread to adjacent structures leading to worsening nasal obstruction, severe and recurrent epistaxis, facial pain, and visual changes.[20][21]

Nasopharyngeal Swab

Nasopharyngeal swabs are routinely performed to test for several viral and bacterial pathogens, including adenovirus, coronavirus (multiple strains), human metapneumovirus, influenza (A and B), parainfluenza, rhinovirus, RSV (A and B), Bordetella pertussis, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. More recently, nasopharyngeal swabs have been the collection method of choice to confirm infection with the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).[22][23]

Other Issues

Post adenoidectomy can lead to the formation of scar tissue, which in the long run could cause a narrowing of the airways. This event could occur, in particular, if muscle tissue or soft tissue suffered partial damage during the surgical approach.[24]

The nasopharyngeal area is the site of investigation for the presence of COVID-19, through the use of a swab.The operator inserts the swab into the nose, and following an imaginary line on a horizontal plane, between the nostril and the ear, collects material.[25]