[1]

Evans P. The postural function of the iliotibial tract. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 1979 Jul:61(4):271-80

[PubMed PMID: 475270]

[2]

Strauss EJ, Kim S, Calcei JG, Park D. Iliotibial band syndrome: evaluation and management. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2011 Dec:19(12):728-36

[PubMed PMID: 22134205]

[3]

Chahla J, Murray IR, Robinson J, Lagae K, Margheritini F, Fritsch B, Leyes M, Barenius B, Pujol N, Engebretsen L, Lind M, Cohen M, Maestu R, Getgood A, Ferrer G, Villascusa S, Uchida S, Levy BA, Von Bormann R, Brown C, Menetrey J, Hantes M, Lording T, Samuelsson K, Frosch KH, Monllau JC, Parker D, LaPrade RF, Gelber PE. Posterolateral corner of the knee: an expert consensus statement on diagnosis, classification, treatment, and rehabilitation. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA. 2019 Aug:27(8):2520-2529. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5260-4. Epub 2018 Nov 26

[PubMed PMID: 30478468]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[5]

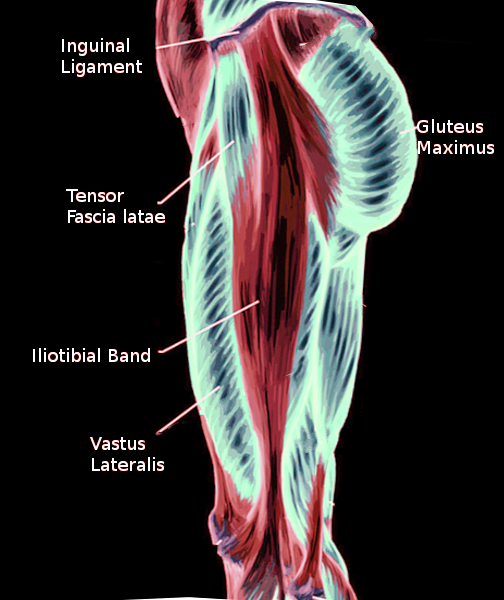

Huang BK, Campos JC, Michael Peschka PG, Pretterklieber ML, Skaf AY, Chung CB, Pathria MN. Injury of the gluteal aponeurotic fascia and proximal iliotibial band: anatomy, pathologic conditions, and MR imaging. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2013 Sep-Oct:33(5):1437-52. doi: 10.1148/rg.335125171. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 24025934]

[6]

Flato R, Passanante GJ, Skalski MR, Patel DB, White EA, Matcuk GR Jr. The iliotibial tract: imaging, anatomy, injuries, and other pathology. Skeletal radiology. 2017 May:46(5):605-622. doi: 10.1007/s00256-017-2604-y. Epub 2017 Feb 25

[PubMed PMID: 28238018]

[7]

Gold M, Munjal A, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Hip Joint. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:():

[PubMed PMID: 29262200]

[8]

Biondi NL, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Vastus Lateralis Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:():

[PubMed PMID: 30335342]

[9]

Fairclough J, Hayashi K, Toumi H, Lyons K, Bydder G, Phillips N, Best TM, Benjamin M. The functional anatomy of the iliotibial band during flexion and extension of the knee: implications for understanding iliotibial band syndrome. Journal of anatomy. 2006 Mar:208(3):309-16

[PubMed PMID: 16533314]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[10]

Tozer S, Duprez D. Tendon and ligament: development, repair and disease. Birth defects research. Part C, Embryo today : reviews. 2005 Sep:75(3):226-36

[PubMed PMID: 16187327]

[11]

Trammell AP, Nahian A, Pilson H. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Tensor Fasciae Latae Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:():

[PubMed PMID: 29763045]

[13]

Ramage JL, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Medial Thigh Muscles. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:():

[PubMed PMID: 30521196]

[16]

Sayed-Noor AS, Pedersen E, Sjödèn GO. A new surgical method for treating patients with refractory external snapping hip: Pedersen-Noor operation. Journal of surgical orthopaedic advances. 2012 Fall:21(3):132-5

[PubMed PMID: 23199940]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[17]

Provencher MT, Hofmeister EP, Muldoon MP. The surgical treatment of external coxa saltans (the snapping hip) by Z-plasty of the iliotibial band. The American journal of sports medicine. 2004 Mar:32(2):470-6

[PubMed PMID: 14977676]

[18]

Ilizaliturri VM Jr, Martinez-Escalante FA, Chaidez PA, Camacho-Galindo J. Endoscopic iliotibial band release for external snapping hip syndrome. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 2006 May:22(5):505-10

[PubMed PMID: 16651159]

[19]

Walbron P, Jacquot A, Geoffroy JM, Sirveaux F, Molé D. Iliotibial band friction syndrome: An original technique of digastric release of the iliotibial band from Gerdy's tubercle. Orthopaedics & traumatology, surgery & research : OTSR. 2018 Dec:104(8):1209-1213. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2018.08.013. Epub 2018 Oct 17

[PubMed PMID: 30341031]

[20]

Pierce TP, Kurowicki J, Issa K, Festa A, Scillia AJ, McInerney VK. External snapping hip: a systematic review of outcomes following surgical intervention: External snapping hip systematic review. Hip international : the journal of clinical and experimental research on hip pathology and therapy. 2018 Sep:28(5):468-472. doi: 10.1177/1120700018782667. Epub 2018 Jun 15

[PubMed PMID: 29902932]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence