Continuing Education Activity

Rupture of the biceps femoris tendon can be treated conservatively or surgically, depending on the severity of the tendon retraction. Most of the patients recover well and are able to return to high-level sports activities if they receive a timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment. This activity describes the causes of biceps femoris tendon rupture, as well as management strategies for patients who present with this condition, and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the management of these patients.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiologies of biceps femoris tendon rupture.

- Summarize the examination procedures for the evaluation of an enthesopathy of the biceps femoris tendon.

- Review the treatment and management options (both conservative and surgical) available for biceps femoris tendon tears.

- Describe some interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication for the evaluation, treatment, and rehabilitation of biceps femoris tendon tears.

Introduction

The location of the biceps femoris muscle is on the lateral side of the posterior thigh. It joins the semimembranosus and semitendinosus muscles, both of which are on the medial aspect of the posterior thigh, to become the hamstring complex. The biceps femoris muscle is the strongest of the hamstring complex and is responsible for flexion, external rotation, and posterolateral stability of the knee.

The biceps femoris muscle has a long and a short head. In some normal variants, the short head of the biceps femoris may be absent. The long head of the biceps femoris muscle originates from the medial aspect of the ischial tuberosity and the inferior aspect of the sacrotuberous ligament. The short head of the biceps femoris muscle arises from the lateral lip of the linea aspera of the femur, proximal two-thirds of the supracondylar line, and the lateral intermuscular septum. These two heads converge to form the biceps femoris tendon and then insert on the fibular head, the crural fascia, and the proximal tibia.

The two heads of the biceps femoris muscle receive innervation by different components of the sciatic nerve. The long head receives innervation from the tibial component of the sciatic nerve, whereas the short head receives innervation from the peroneal component of the sciatic nerve. This unique innervation pattern of the biceps femoris muscle may result in incoordination of both heads and vulnerability to a sports injury.[1]

Injury to the biceps femoris muscle has an association with decreased flexion force and rotational stability of the knee. Brunet (1987) observed that the flexion force had a 75% decrease if the biceps femoris tendon gets transferred to the fibular collateral ligament. By transferring either a part of or the entire biceps femoris tendon to the fibular collateral ligament, it is anticipated to resist the anterolateral rotatory instability of the knee, which usually arises from the anterior cruciate ligament insufficiency and injury to the lateral capsule of the knee.[2] On the other hand, Frazer (1988) showed that the biceps femoris muscle had increased activity in the knees with torn anterior cruciate ligaments. The electromyographic activity of the biceps femoris tendon also increased during quadriceps setting and straight leg raising exercises.[3]

Rupture of the biceps femoris tendon can be treated conservatively or surgically, depending on the severity of the tendon retraction. Most of the patients recover well and are able to return to high-level sports activities if they receive a timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Recurrence is highly common.

Etiology

The biceps femoris tendon rupture usually develops following sudden knee hyperextension with concomitant hip flexion which can be encountered in running athletes. The most common sport associated with biceps femoris tendon injury is football (soccer). Some case series reported that the injury developed while playing hockey, jogging, and water skiing.[4][5][6]

Risk Factors [7]

- Previous biceps femoris tendon injury increases the chance of a new injury by 6 folds. This is mainly due to the weak scar tissue increasing the chances of recurrence.

- Sharp training without enough warm-up.

- Weak hamstrings relative to quadriceps with a ratio < 0.6

- Unequal hamstring strength between both lower limbs with a difference greater than 15%

- Limited hip extension.

- Leg length discrepancy with the shorter leg has tighter hamstrings.

Epidemiology

Biceps femoris tendon avulsion of the ischial tuberosity or complete rupture is rare, and only a few case reports mention it. Avulsion of the ischial tuberosity is usually the case in skeletally immature and often seen in water skiers. However, in adults, rupture at the myotendinous junction is the most frequently injured part of the hamstring complex since it is the most powerful leg flexor and a crucial dynamic stabilizer of the knee.[8] Often occurs in sprinting or sports involving rapid acceleration and is usually injured during the sudden takeoff phase of running.

Pathophysiology

The biceps femoris muscle becomes active in the late mid- or terminal swing phase of the gait cycle. This is when an injury is likely to occur as suggested by the majority of the literature.[9] This is when the muscle eccentrically contracts and the fibers are at maximal elongation. The muscle contracts eccentrically to control the angular acceleration of the knee during its extension. The tendon is more vulnerable to injury during an eccentric contraction than a concentric contraction. Aging and muscle fatigue also render the muscle more susceptible to suffer injury.

History and Physical

The patients suffering from the biceps femoris tendon rupture may complain of sharp pain at the back of the knee and posterior thigh following hyperextension of the affected knee. They may feel a pop on the affected knee during knee extension. In proximal avulsion cases, the patient can complain of pain on sitting. Most of the victims had an injury while performing activities such as soccer, running, or water skiing. The injury usually renders the patient unable to walk or they walk with avoidance of hip and knee flexion, otherwise known as "stiff-legged" gait.

The clinician may palpate a gap next to the ruptured biceps tendon. Sometimes, the examiner can also palpate a subcutaneous hematoma. Tenderness over the posterolateral aspect of the affected knee (distal tendinous insertion) is common. Tenderness can also be present over the ischial tuberosity or myotendinous junction. The flexion force of the affected knee may decrease in severe cases. Hamstring strength can be assessed with the patient prone and knee flexed to 90 degrees. Strength is assessed and compared to the contralateral side. The patient may experience peroneal nerve weakness e.g foot drop. A reduced popliteal angle on the injured side can be assessed. With the patient supine, the ipsilateral hip and knee are flexed to 90 degrees. The examiner slowly extends the knee. Where posterior thigh pain is experienced, the knee angle is calculated and compared with the contralateral side.

Provocative tests: These tests are positive if the patient experiences pain at the posterior thigh/knee in cases of injury, tendinopathy, or strain.

- Puranen-Orava Test: the patient is asked to position the heel of the affected side at a high surface so that the hip is 90 degrees flexed and the knee is fully extended. The patient is asked to reach for the toes.

- Bent-knee stretch test: Patient is positioned supine, hip and knee are maximally flexed and The examiner slowly extends the knee.

- Modified bent-knee stretch test: the patient is positioned supine, hip and knee are maximally flexed, and then the examiner rapidly fully extends the knee.

Evaluation

Imaging modalities can assist in defining the extent and severity of the biceps femoris tendon injury.

Plain radiographs: anteroposterior view of the pelvis, anteroposterior and lateral views of the femur may show an avulsed bony fragment of the ischial tuberosity.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): due to variable injury patterns, prompt diagnosis with an MRI is important [10]. MRI can be used to assess the degree of tendon retraction and integrity of the surrounding bony structure. There will be increased signal intensity in T2 weighted images in cases of partial tears. In contrast to increased signal intensity in T1 weighted images that is usually seen in cases of tendinopathy.

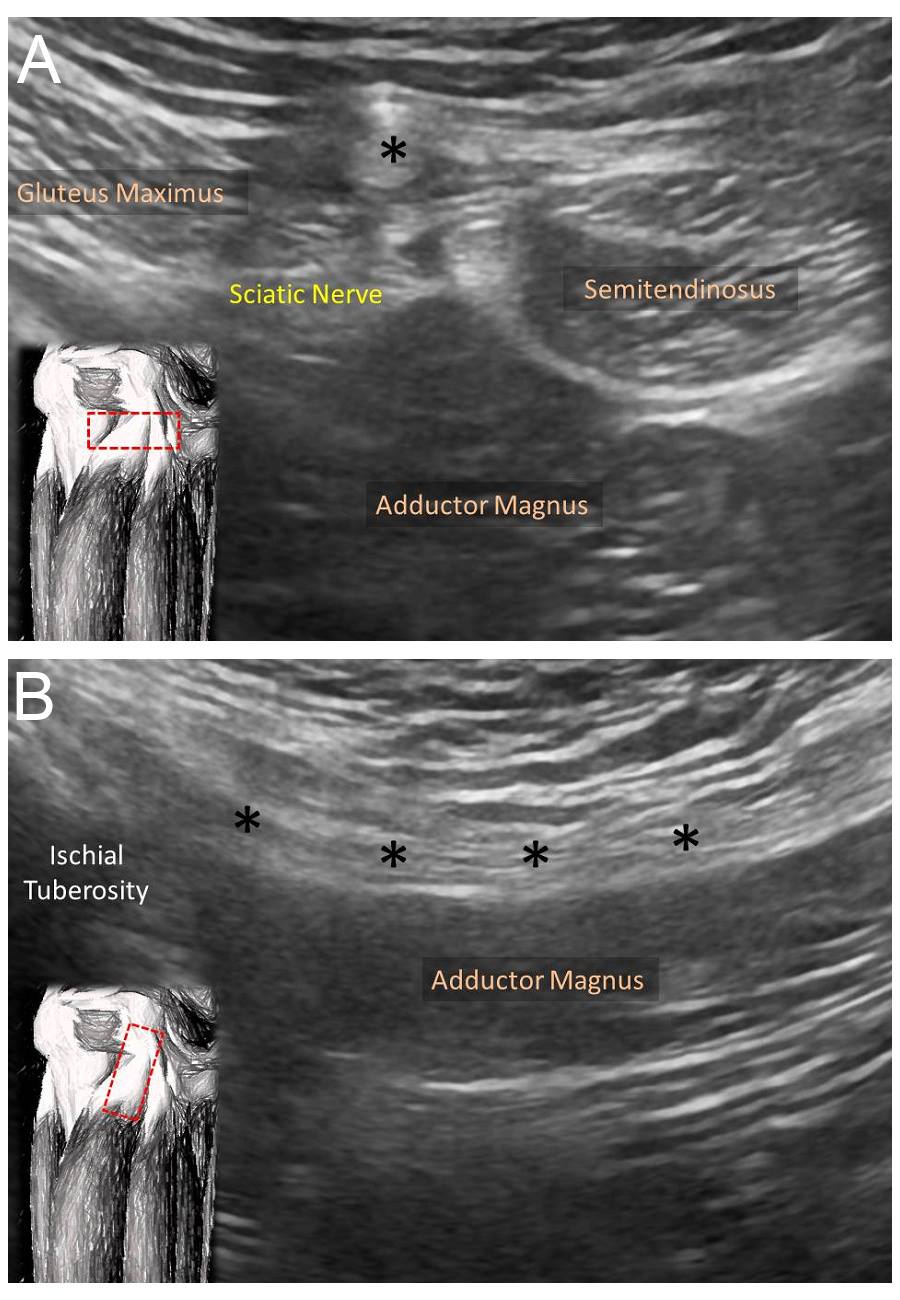

Ultrasonography offers the advantage of zero radiation and is relatively inexpensive. Besides, sonography allows a dynamic assessment, which can be employed to assess the reciprocal movement of the biceps femoris tendon against the surrounding soft tissues (Figure 1). Color or power Doppler ultrasound can be used to assess intra-tendinous/muscular hypervascularity, which is indicative of neovascularization or inflammation of the injured tendon. Comparison with the contralateral side may be valuable for diagnosis.[1]

Treatment / Management

Non-operative treatment [11]: includes rest, ice, non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs, gentle stretching, and therapeutic exercise for 4 to 6 weeks.[12] Isolated rupture of the biceps femoris tendon and ruptures at the myotendinous junction typically receives non-operative therapy. Cohen (2007) indicated that in the patients with biceps femoris tendon rupture with tendon retraction less than 2cm, most athletes can return to high-intensity sport (e.g., professional football) approximately six weeks after injury. The ruptured tendon gradually heals, allowing the affected knee to return to full strength. Additional abdominal, hip, and quadriceps stretching and strengthening will help prevent reinjury. Hamstring strengthening aims at balancing hamstring-quadriceps power.

Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP): ultrasound-guided injection is recommended within 48 hours of the acute injury.

Operative repair [13] yields 80% return to preinjury level and a return to sports at 6 months postoperatively. It is indicated in the following scenarios:

- Avulsion of the tendon proximally off the ischial tuberosity.

- Partial tears with persistent symptoms after 6 months of nonoperative management.

- Concomitant hamstring tendon tear ( semitendinosus or semimembranosus) especially with more than 2 cm retraction in young and active patients.

Open reduction and internal fixation: This is indicated for an avulsed bony fragment with more than 2 cm of displacement and in chronic symptomatic avulsed bony fragments. Direct open reduction and fixation with partially or fully threaded screws with washers. Suture anchors can be used to supplement fixation. It does have a good union rate.

Surgical Technique for biceps tendon repair: The patient is usually positioned prone to allow knee flexion to relieve hamstring tension if needed. Transverse incision over the gluteal crease that can be extendible in T configuration to retrieve a retracted tendon. The underlying fascia is usually split vertically and hematoma evacuated. Care should be taken to avoid sciatic nerve injury that courses on average 1.2 cm lateral to the most lateral aspect of the ischial tuberosity. The insertion site at the ischial tuberosity is scrapped with a curette or periosteal elevator. Sutures anchors are used to attaching the tendon back to the ischial tuberosity. In chronic cases, allograft may be needed.

Most cases recover well after a non-operative treatment or a timely repair. But no specific guidelines address when should be treated surgically. Several case studies suggest that a complete biceps femoris tendon rupture should undergo surgical treatment.[14]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes:

- Ischial tuberosity disease

- Hamstring enthesopathy

- Referred pain from the sacroiliac joints, lumbar spine, pubic symphysis, gluteal muscles

- Sciatica

- Stress fractures of the pelvis or the fibular neck

Clinicians should be mindful that not all posterior thigh pain derives from the biceps femoris tendon injury. Besides, the biceps femoris tendon injury often occurs with an injury of the entire hamstring complex.[1]

Staging

MRI Classification ( T2 weighted images):

- Grade I: High signal intensity around the tendon or myotendinous junction but no disruption.

- Grade II: Hight signal intensity around or within the tendon or the muscle along with fiber disruption involving less than half the width of the tendon or the muscle.

- Grade III: Tendon or muscle disruption greater than half of the width of the involved tissue.

Prognosis

The prognosis of the biceps femoris tendon injury is good if the injury receives prompt and appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Most athletes return to professional sports after treatment.[15]

Complications

Although complete rupture of the proximal biceps femoris tendon is not common, the patients may have weakness, pain, and sciatic neuralgia if the injured tendon does not receive proper treatment.[1][15] There is a high level of complications reported with operative management especially with repairing chronic cases in comparison with acute cases (within 6 weeks of injury).

The following complications have been reported:

- Recurrence: The most common complication. Higher risk with weak hamstring, hamstring-quadriceps strength imbalance, and premature return to activities.

- Peroneal nerve injury: This is usually a self-resolving neuropraxia with distal injuries.

- Sciatic nerve injury: This is reported in chronic cases where there is scarring around the nerve. It indicates nerve exploration.

- Hamstring syndrome: This complicates the nonoperative management of avulsion injuries. The patient will experience a localized posterior buttock and ischial tuberosity pain. Treatment usually involves surgical release and sciatic nerve injury.

- Nonunion of the ischial tuberosity: occurs with nonoperative management of displaced (> 2 cm) bony avulsion fractures. Treatment is open reduction and internal fixation with or without bone graft.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperatively patients are advised on partial weight-bearing for 4 to6 weeks with the knee flexed 40 degrees to protect the repair.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Education should be provided to the public as more and more people participate in high-intensity exercises. The healthcare providers should offer the best practice according to evidence-based medicine. Athletes and young active people should be counseled on injury prevention exercises. e.g Nordic hamstring exercise athlete kneels and assistant supports their heels to the ground then they start leaning forward till prone then backward, stretching their hamstrings. This exercise has been shown to reduce hamstring injury up to 70 %.[16] In addition to exercises of specific hamstring muscles e.g. Hip extension exercises target the long head of the biceps femoris and semimembranosus. Knee flexion exercises target semitendinosus and the short head of the biceps femoris.[17][18]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional approach for biceps femoris tendon rupture is recommended. Biceps femoris tendon rupture is relatively common among young athletes and the physically-active population. Many patients visit the emergency department or the primary care provider once they have an injury. Hence, these professionals need to know about the diagnosis and management about the disorder. The key to prevent these injuries is education about the importance of warmup and stretching before exercise. For most patients, the prognosis is good. The non-operative treatment usually provides optimal symptom relief and functional recovery. The indication for surgical intervention remains uncertain.