Introduction

Obesity in the United States (US) has become synonymous with heart disease, diabetes, and early death. Research supports the link between obesity and adverse health outcomes.[1] Obesity is one of the most challenging public health issues not only in the USA but globally. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there are 93 million adults with obesity in the US, representing 39.8% of the adult population. Obesity is a major risk factor for the development of diabetes, heart disease, and is a leading cause of preventable death. Estimates are that the medical cost of obesity ascends to 147 billion dollars per year. There is no medical treatment for obesity that works consistently or in a predictive manner. To date, bariatric surgery is the only known treatment for obesity.

Bariatric surgery has gained particular importance due to its success in reversing the abnormal metabolic profile; after bariatric surgery, there is a marked improvement in the management of diabetes, hypertension, sleep apnea, arthritis, and the metabolic syndrome.[2] This surgical approach to obesity has been significantly more successful at sustained weight loss in patients with extreme obesity compared to diet and medical interventions.[3] Also, there is significant improvement in overall mortality associated with bariatric surgery.[2] However, patients with obesity have several comorbidities that increase the risk of any surgery; thus, prior to surgery, a preoperative workup is highly recommended.

This activity describes the preoperative preparation and workup of a patient with obesity undergoing bariatric surgery and the role of an interprofessional team evaluation during the peri-operative period.[4][5]

Indications

The surgical management of obesity has gained popularity in the last decade with more than 200000 bariatric procedures performed in the US and Canada every year.

Obesity is generally classified based on body mass index (BMI), calculated by dividing the weight in kilograms (kg) by the square of height in meters (m). A BMI of 20 to 25 kg/m2 identifies a subject with a normal weight, whereas a BMI of 26 to 29.9 kg/m2 is considered overweight, and a BMI of 30 to 39.9 kg/m2 is considered obese. A patient with a BMI over 40 kg/m2 is called extremely obese; a patient with a BMI over 50 kg/m2 is superobese, and with a BMI greater than 60 kg/m2 is super-super obese. According to the SAGES (Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons) guidelines for bariatric surgery, the indications for weight loss surgery are as follows:

- BMI more than 40 without comorbidities

- BMI 35 to 39.9 with at least one serious comorbidity including diabetes, hypertension, sleep apnea or limitations in the quality of life

- BMI 30 to 34.9 with metabolic syndrome or diabetes that is uncontrolled with medical therapy

It is important to note that upon entrance to a bariatric surgery program and before proceeding with surgery, patients should participate in a guided weight loss program with exercise and lifestyle modifications; this will help ensure that the patient can make the commitment necessary to undergo the postoperative nutritional restrictions of the procedure.[6][7]

Weight reduction surgery is obtainable through malabsorptive, restrictive, or a combination of both approaches. Malabsorptive methods such as jejunoileal bypass and biliopancreatic bypass, are rarely performed today. Restrictive procedures include the vertical-banded gastroplasty (VBG), adjustable gastric banding (AGB), and sleeve gastrectomy. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is a combination of gastric restriction and bypass of a small segment of the small intestine. The GS procedure is currently the most popular bariatric surgery performed in the US due to its relative technical ease and low complication rates; it also correlates with significant improvements in comorbidities and comparable weight loss to other more complex bariatric procedures.

Preparation

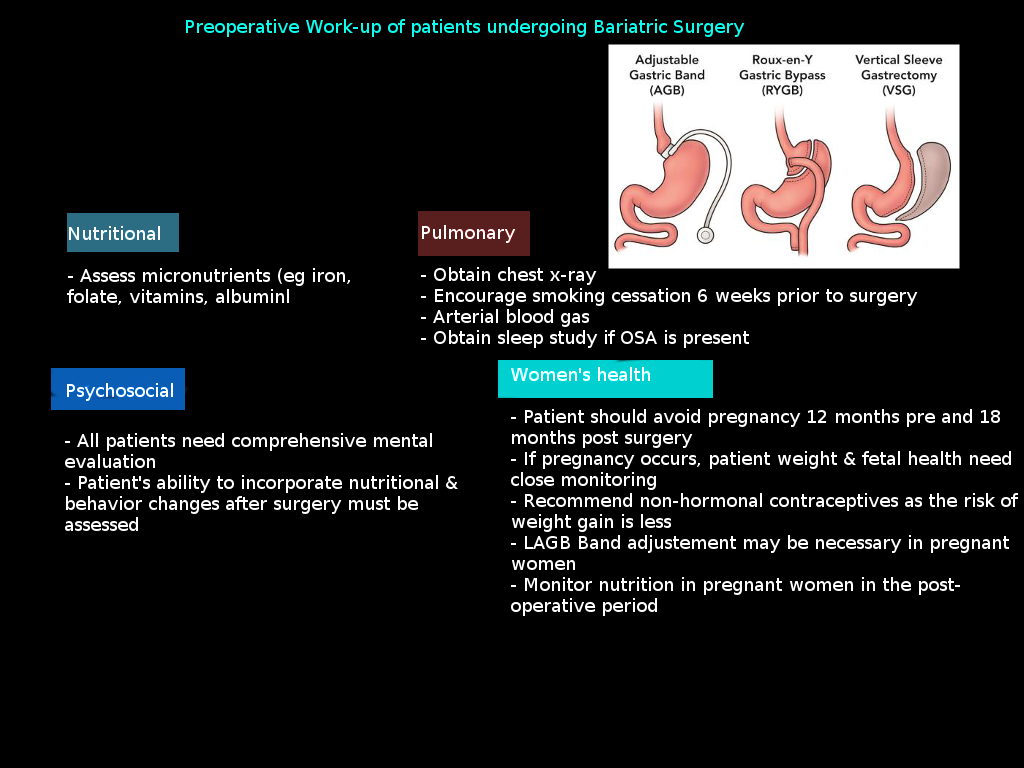

The preoperative evaluation should be holistic, integral, and include an assessment by an interprofessional team encompassing endocrinologists, dieticians, psychologists, anesthesiologists, nurses, cardiologists, and the surgeon. Several steps during the pre-op evaluation should take place to ensure a positive outcome after the bariatric surgery procedure.

Psychological Evaluation

Patients should be psychologically fit to undergo bariatric surgery. A psychological clearance is one of the first steps in the preoperative workup of the patient. Patients should undergo evaluation for a history of mental disorder, depression, eating disorders, prior weight loss attempts, compliance with therapy, and substance misuse.

Patients identified to have alcohol dependence need a referral for rehabilitation and detoxification before the procedure. The patient should achieve at least one-year abstinence prior to surgery, solidly documented.

Smoking cessation should be encouraged and documented before proceeding with the operation; cessation of smoking has demonstrated improved outcomes and reduce postoperative complications.

The support system available for the patient should also be evaluated. Studies have shown that patients with strong family and community support are more likely to have better outcomes.

Nutritional Evaluation

Nutritional assessment and patient education will help guide the patient towards dietary modifications that are necessary after surgery. Education regarding patient expectations should also be included to ensure clear objectives regarding weight loss. As a general rule, a patient undergoing sleeve gastrectomy should expect to lose about 60 to 65 percent of excess body weight in 2 years, and a patient undergoing gastric bypass should expect a weight loss of 70 to 75 percent of excess body weight in the same period. Weight maintenance strategies should be a topic of discussion with the patient.

Glycemic control in the diabetic patient undergoing bariatric surgery is of extreme importance and should be encouraged and monitored. A licensed dietician typically performs the nutritional evaluation.

Weight Loss Plan

A guided weight loss plan is necessary. A documented weight loss program can improve outcomes after surgery and does not preclude the patient from undergoing weight loss surgery in most cases.

The weight loss plan should include nutritional assessment and a guided exercise plan. Weight loss goals should be delineated and monitored during every visit of the patient during the preoperative period.

Failure to lose weight due to lack of adherence to the plan and diet can be a predictor of how reliable the patient will be with lifestyle modifications needed in the postoperative period. A failure to lose weight even after following the plan should also be documented so that more aggressive support can be provided before and after the bariatric procedure.

Medical Clearance

A complete evaluation is necessary before the patient is cleared to undergo bariatric surgery. This evaluation should include a detailed history and physical, review of past medical and surgical history, a review of psycho-social factors that could influence weight loss (employment, housing, family core), laboratory workup and anthropometric measurement. Functional status should be documented as it directly correlates with perioperative outcomes.

The patient should also complete screening for cardiac disease and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Patients with OSA symptoms should be referred for a sleep study (see below Anesthesiological Preoperative Considerations).

Laboratory workup should include a comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, levels of iron, vitamins, and folate, type and screen, hemoglobin A1C, and a coagulation panel.

Preoperative Imaging

There is no consensus regarding the imaging modalities that should be obtained before a bariatric procedure, and this also depends on whether the patient had previous bariatric surgery or any type surgery that may have affected the anatomy of the gastrointestinal tract. Such imaging can be used to guide the surgeon determine what type of bariatric surgery to offer the patient.

An abdominal ultrasound is necessary for patients undergoing gastric bypass to identify possible liver pathology and cholelithiasis due to the high prevalence of the latter in this patient population; also, after this procedure, there is no option of endoscopic intervention to explore the biliary tract if the patient develops choledocholithiasis. It is important to mention that even after identifying cholelithiasis, there is no consensus on the management of this condition in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. However, patients with symptoms of acute or chronic cholecystitis or symptomatic cholecystitis should have their gallbladder removed during the bariatric procedure, as weight loss will only worsen their symptoms.[10]

Other Preoperative Considerations

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is not routinely a recommended procedure in the workup for bariatric surgery. The American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery advises the use of endoscopy only for patients with significant gastrointestinal symptoms.[7][11][12][13]

ANESTHETIC PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Anesthesiological evaluations are of fundamental importance as obesity correlates with various comorbidities that can make intraoperative management difficult and complicate the postoperative course.[14] Obesity-related conditions include heart disease, hypertension, stroke, type 2 diabetes, gastroesophageal reflux disease, among others. The evaluation of history and clinical-instrumental assessment are important to assess the degree of functional impairment and can help the clinician determine which of the disorders can be corrected or improved (e.g., improvement of blood glucose, blood pressure). Furthermore, a careful drug history is necessary, as several agents such as diet drugs and appetite suppressors can impact the anesthetic management by inducing cardiopulmonary and gastrointestinal problems.

Evaluation of the Cardiorespiratory Status

Enrolled patients should be evaluated for ischemic heart disease, systemic and pulmonary hypertension, right or left ventricular failure signs, and sleep-disordered breathing. OSA is usually investigated through the 8-item STOP-Bang Questionnaire (S=Snoring; T=Tired; O=Observed and includes the following:

- 'Has anyone observed you stop breathing or choking/gasping during your sleep?'

- P=Pressure

- B=BMI over 35

- A=Age older than 50

- N=Neck size

- G=Gender: male greater than female[15]

Other screening tools that are also options include the Epworth Sleepiness Score and the Berlin Questionnaire. Patients at risk for OSA should be evaluated using an over-night polysomnography test. Patients diagnosed with OSA may benefit from non-invasive preoperative ventilation (e.g., continuous positive airway pressure or bilevel positive pressure),[16] primarily when an obesity-related sleep disorder is associated with daytime hypercapnia (arterial carbon dioxide tension greater than and equal to 45 mmHg) or the so-called obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS) that may cause alveolar hypoventilation. The utility of a routinely spirometry testing is debatable as, probably, it is indicated only in high-risk patients.[17]

In addition to the standard ECG that may demonstrate signs of right ventricular hypertrophy, further cardiac evaluation may include stress echocardiography and cardiopulmonary exercise testing.

Airway Management

Airway management can represent a severe challenge for anesthesiologists. Difficult or failed intubation, indeed, is more common in patients with obesity than in the nonobese population.[18] Obesity correlates with a 30% greater chance of difficult or failed intubation. Thus, preoperative identification of patients at high risk for airway management problems is mandatory. Predictive scores of difficult intubation such as thyromental distance and neck circumference as well as the range of motion of the neck and larynx must have a careful evaluation. The Mallampati score is the most important parameter. It evaluates the visibility of the base of the uvula, faucial pillars, and soft palate; and classifies patients into four classes.

In class 1, these structures are easily visible, and class 4 identifies an anatomical condition with less visible structures. Mallampati classes 1 and 2 correlate with relatively easy intubation, and classes 3 and 4 correlate with a higher probability of difficult intubation. Of note, research shows that only a large neck circumference (over 40 cm) and a Mallampati score greater than or equal to 3 are predictors of potentially difficult intubation, whereas BMI, or weight, are not always predictive of difficult intubation.[19]

Other Anesthetic Considerations

There is also a concern for venous access in patients with obesity; thus before anesthesia, one should closely examine the extremities for good veins or consider inserting of a central line; IV access is vital for induction of anesthesia, administration of medications and hydrating the patient. At the same time, the pharmacist should recommend the appropriate dose of medications based on body weight.

All these difficulties and the possibility that rare complications of anesthesia (e.g., anesthesia awareness) may occur more frequently in the patient with obesity, must be clearly explained to the patient.[20]

Bariatric surgery is an elective procedure, and it is essential to optimize the patient's functional and health status prior to surgery.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Management of obesity requires an interprofessional team from the moment the patient presents to the bariatric surgery clinic, and following after the procedure is done to monitor weight loss outcomes. This team consists of nurses, dietitians, psychologists, case managers, patient care coordinators, and physicians in multiple specialties, allowing a holistic approach to the management of obesity. Psychologic and behavioral evaluation, nutritional evaluation, medical clearance, and anesthesiology evaluation are mandatory during the pre-operative work-up of the patient undergoing weight loss surgery. [Level II] Additional testing should be tailored to individual patient needs; this includes EGD, sleep apnea testing, radiology studies, bone density tests. [Level III] Glycemic control should be achieved before any bariatric intervention to ensure the best outcomes. [Level II] While a preoperative weight loss plan should be in place, the inability to lose weight or weight gain during the preoperative period should not disqualify the patient for a weight loss procedure. [Level III] Pharmacists may assist the team with guidance in selecting weight loss medications, medication reconciliation, and being available post-surgically for pain control. Nursing needs to assist in counseling the patient in the procedure's preparatory timeframe. They will also assist during the procedure, and in the surgical followup until the patient can be sent home.

Given the strict and extensive criteria for a patient to qualify for these types of surgeries, the entire process from preparation through post-procedural followup and support requires the efforts of a coordinated interprofessional team, including physicians, nurses, dieticians, and mental health professionals, all working collaboratively to provide care and support for patients that need weight loss surgery. [Level V]

Currently, there are diverse institutional guidelines as well as insurance requirements for patients requiring weight loss surgery. Further research is needed aiming towards standardization and the creation of a pathway for pre-operative management and the preparation of patients with obesity for bariatric surgery.[22][23][6][24]

Also, while public health efforts to curb obesity and achieve population health are applaudable in their efforts, these preventive measures may not be targeting health in the right way, and as such inadvertently harming certain vulnerable populations. The current focus on obesity does not address all aspects of health. More effort needs to be made to promote a more well-rounded approach to population health and move away from targeting certain populations. Public health officials should strive to move away from labels and toward more sustainable definitions of general well-being for long-term success.