Introduction

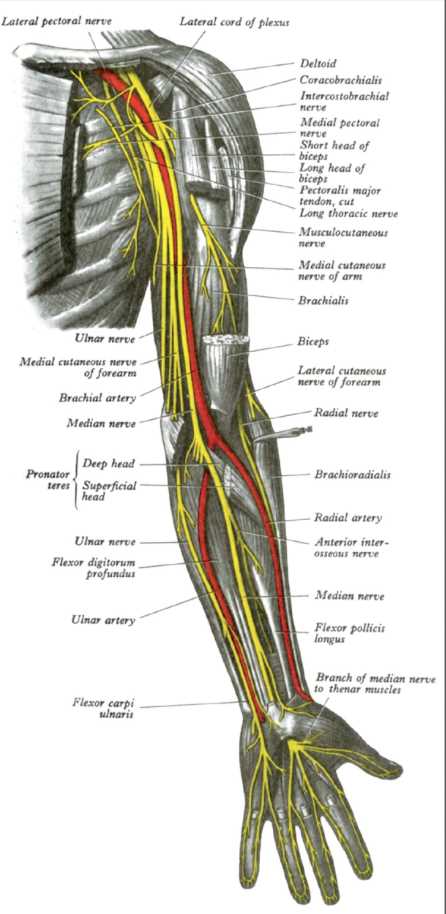

The arm is the region of the upper extremity extending between the shoulder and elbow joints. The nerves found within the arm are terminal branches of the brachial plexus and serve to innervate muscles of the upper extremity and transmit sensory information to the higher processing centers of the brain.[1] Primary pathology involving these nerves arises from either external trauma or iatrogenic damage. Regardless of etiology, damage to these structures can result in motor and sensory palsies affecting innervated muscles and corresponding dermatomes (see Image. Arm Nerves).

Structure and Function

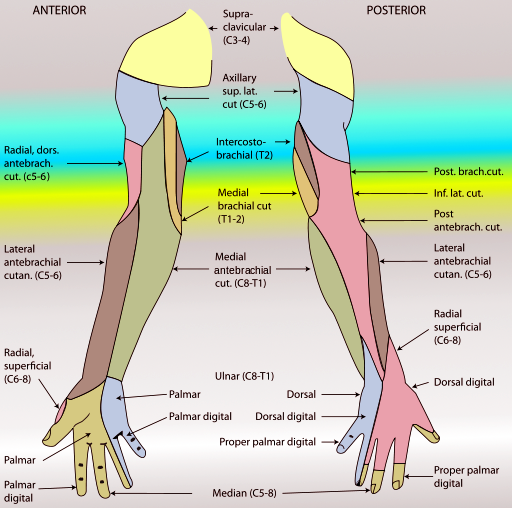

The terminal branches of the brachial plexus include the axillary, musculocutaneous, radial, ulnar, and median nerves. Each is responsible for specific motor and sensory innervation of the upper extremity. This review covers physical course and sensory innervation here, while motor innervation is the topic in the section below.[2][3]

The axillary nerve originates from the posterior cord and carries nerve fibers from the C5 and C6 levels. After arising from the brachial plexus, it travels inferior and posterior to the shoulder joint capsule accompanied by the posterior circumflex humeral artery. This neurovascular bundle appears in the quadrangular space. The nerve then splits into superficial and deep branches. The sensation of the lateral proximal arm derives from the superior lateral cutaneous branch.[4][5]

The musculocutaneous nerve originates from the lateral cord and carries fibers from C5-C7. It pierces the belly of the coracobrachialis and then travels distally between the biceps and brachialis muscles. The nerve terminates as the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm, which is responsible for sensation along the lateral forearm.[6]

The radial nerve arises from the posterior cord and carries fibers from C5-T1. It begins its course medial to the humerus but quickly crosses posteriorly, running in the spiral groove close to the deep brachial artery and the bone surface. Distally, it pierces the lateral intermuscular septum, entering the anterior compartment of the arm. As it enters the forearm, the nerve splits into a deep motor branch (posterior interosseous nerve) and a superficial sensory branch. The radial nerve is responsible for cutaneous innervation of the posterior arm (via the posterior cutaneous nerve of the arm), the lateral arm (via the inferior lateral cutaneous nerve of the arm), the posterior forearm (via the posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm), and the dorsal aspect of the lateral 3.5 fingers (via superficial digital branches).[7][8]

The ulnar nerve originates from the medial cord and carries fibers from C8-T1. It descends distally along the medial aspect of the arm. It passes posterior to the medial epicondyle through the cubital tunnel. In the forearm, it runs between the 2 heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris. At the wrist, it travels superficial to the flexor retinaculum and through the Guyon canal to enter the hand. Before entering the Guyon canal, it gives rise to dorsal and palmar cutaneous branches, which innervate the dorsal 1.5 digits and palmar aspects of the proximal hand, respectively. The nerve terminates as superficial (provides sensory innervation to the palmar 1.5 digits) and deep (provides motor innervation) branches.[9]

The median nerve emerges from the lateral and medial cords and carries fibers from C5-T1. It runs medial to the biceps and brachialis and lateral to the brachial artery. It enters the forearm under the biceps aponeurosis and through the 2 heads of pronator teres. It gives rise to the anterior interosseous nerve in the forearm and then continues distally through the carpal tunnel. The median nerve is responsible for cutaneous innervation of the palm (via the palmar cutaneous nerve branching before the carpal tunnel) and the volar aspects of the lateral 3.5 digits (via superficial digital branches)(see Image. Forearm Nerves).[10]

Embryology

The nerves of the arm are considered a part of the peripheral nervous system. As such, they are derived primarily from neural crest cells. During embryogenesis, the upper limb derives from the developing limb bud starting at approximately 26 days after fertilization. Motor axons from the spinal cord enter the limb buds first during the fifth week of development, followed shortly afterward by the sensory axons. Each of these preliminary nerves is then surrounded by primordial Schwann cells derived from neural crest cells, ultimately forming the myelin sheath. As the limb buds elongate and rotate, they carry their corresponding nerves, leading to the classic dermatomal pattern seen in a fully developed human.[1][11][12][1]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Much of the research regarding blood supply to the arm nerves was the result of the introduction of the free vascularized nerve graft in 1976, which required a deep understanding of the blood supply to peripheral nerves. To date, one of the prevailing theories is that of the angiosome, a 3-dimensional block of tissue supplied by a particular source artery. Under this theory, nerves traversing a particular angiosome would get supplied by branches of the adjacent source artery. This theory is supported by evidence that transplanted nerves induce angiogenesis of nearby arteries, thus receiving reliable blood supply.[13][14]

One study identified 2 unique methods of blood supply to peripheral nerves. The first was an epineurial longitudinal arterial system that accompanied each nerve. Among nerves without such an epineurial vessel, small branches from adjacent muscles provided blood. When investigating the nerves separately, the axillary nerve received supply from the brachial and posterior circumflex humeral angiosomes. The musculocutaneous nerve was provided entirely by the brachial angiosome. The radial nerve got its supply from the brachial, profunda brachii, and radial angiosomes. The brachial and ulnar angiosomes supplied the ulnar nerve. The median nerve's vascular supply was via the brachial, ulnar, and radial angiosomes.[14] Lymphatic supply to the nerves has not been well described.

Muscles

The nerves of the arm are responsible for providing motor innervation to all of the muscles within the upper extremity.[15][16][17]

Axillary Nerve

- The axillary nerve innervates the deltoid and teres minor.

Musculocutaneous Nerve

The musculocutaneous nerve is responsible for innervating the flexors of the arm, including the biceps brachii, coracobrachialis, and the medial aspect of the brachialis.

Radial Nerve

- The radial nerve innervates the triceps brachii, lateral aspect of the brachialis, anconeus, brachioradialis, and extensor carpi radialis longus.

- Through its deep branch, it innervates the extensor carpi radialis, brevis, and supinator.

- Through the posterior interosseous nerve, it innervates the extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi, extensor carpi ulnaris, abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis, extensor pollicis longus, and extensor indicis.

Ulnar Nerve

- The ulnar nerve does not innervate any of the muscles of the arm.

- In the forearm, it innervates the flexor carpi ulnaris and the medial half of the flexor digitorum profundus.

- In the hand, it innervates the hypothenar muscles, medial 2 lumbricals, interossei, adductor pollicis, and the deep head of the flexor pollicis brevis via its deep branch.

- It innervates palmaris brevis through its superficial branch.

Median Nerve

- The median nerve does not innervate any of the muscles of the arm.

- In the forearm, it innervates the pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus, and flexor digitorum superficialis.

- Through the anterior interosseous nerve, it innervates the flexor pollicis longus, pronator quadratus, and the lateral half of the flexor digitorum profundus.

- In the hand, it innervates the thenar muscles and the lateral 2 lumbricals.[15][16][17]

Physiologic Variants

Anatomists have described variations of the brachial plexus, and its distal branches have been described for many decades. One study described a series of cadaveric specimens where innervation of the long head of the triceps brachii arose from a branch of the axillary nerve rather than the traditional radial nerve.[18] Variations regarding the musculocutaneous and median nerves have also been described, including spans where the nerve fibers from each may run together for some distance before separating again. Connecting branches between the median and musculocutaneous nerves have been observed.[19][20] In 1 study of 167 cadaveric arms, variations of the relationship of the musculocutaneous nerve to the coracobrachialis were also described, with the nerve not perforating the muscle in 1.8% of cases. In 1 case, the musculocutaneous nerve was absent altogether. This same study documented a few variations of the ulnar, radial, and axillary nerve, with most instances focusing on nerves that were thinner than normal.[21]

Surgical Considerations

Orthopedic interventions of the arm primarily involve open reduction and internal fixation of humerus fractures. Because of the proximity of surrounding neurovascular structures, primarily the radial nerve, to the bone surface, each surgical approach has dangers that merit consideration.[22][23]

Anterior Approach

Provides a versatile approach, providing ample exposure to the humeral shaft. Despite entering the anterior compartment of the arm, the radial nerve is in danger as it sits along the spiral groove on the back of the middle third of the humerus. This risk is particularly heightened when drilling or installing hardware in an anteroposterior axis where it is essential to not over-penetrate the posterior cortex. The radial nerve can also be damaged in the distal third of the arm as it crosses through the intermuscular septum and lies between the brachioradialis and brachialis muscles. The anterior approach also poses a danger to the axillary nerve, which can be damaged as it runs along the undersurface of the deltoid muscle if there is an excessive retraction of the muscle.

Posterior Approach

Similar to the anterior approach, it provides ample exposure to the humeral shaft. It may be preferred when there is known damage or transection of the radial nerve, as the nerve is directly visible in this approach. In patients with an intact radial nerve, it is at risk as it traverses the spiral groove along the posterior aspect of the humerus. The posterior cutaneous nerve is identifiable and traced proximally to identify the radial nerve. When plating a fracture using the posterior approach, ensure the nerve does not get entrapped between the plate and bone.

Distal Humerus Approach

The distal humerus can be approached through local incisions, both anterolaterally and medially. The anterolateral approach is useful for distal humerus fractures and exploration of the distal radial nerve. The radial nerve requires identification before incising through the brachialis muscle as it runs between the brachialis and brachioradialis. The medial approach is appropriate for isolated fractures of the medial column of the distal humerus and repair of the ulnar collateral ligament. The forearm's posterior branch of the medial cutaneous nerve should be preserved during superficial dissection. The ulnar nerve is identifiable as it runs behind the medial epicondyle.[22][23]

Clinical Significance

Because of their long course through the arm, each of the nerves is vulnerable to damage, particularly in the setting of trauma or surgery.

Axillary Nerve

The axillary nerve can suffer damage with anterior, inferior dislocations of the shoulder joint, through prolonged compression of the axilla, and with fracture of the surgical neck of the humerus. Injury leads to loss of arm abduction, deltoid atrophy, and loss of sensation over the lateral arm.[24]

Musculocutaneous Nerve

Damage to the musculocutaneous nerve can occur during surgery with overzealous retraction of the coracobrachialis. Injury leads to weakened flexion at the elbow and shoulder, weakened supination, and a corresponding loss of sensation.[23]

Radial Nerve

The radial nerve can get compressed at the axilla, known as Saturday night palsy. Injury at this level leads to loss of extension of the forearm, wrist, and fingers, combined with sensory loss in the radial nerve distribution. In the arm, the radial nerve can incur damage with a mid-shaft humeral fracture leading to weakness of wrist and finger extension and corresponding sensory loss distally. Damage can also occur in the forearm.[7][25]

Ulnar Nerve

Ulnar nerve injury can occur with a fracture of the medial epicondyle, resulting in abduction of the wrist, loss of abduction and adduction of the fingers, loss of flexion at the MCP joints, and hypothenar atrophy. Loss of thumb adduction results in a positive Froment sign. The ulnar nerve can suffer an injury at the wrist.[26]

Median Nerve

The median nerve can become impaired with a supracondylar humerus fracture. Injury at this level can cause adduction of the wrist, loss of pronation of the forearm, weakness of wrist flexion, loss of thumb flexion, thenar muscle atrophy, and loss of sensation over the corresponding area. When attempting to form a fist, the radial digits do not flex, resulting in the hand of the benediction sign. At rest, loss of thumb abduction leads to the ape hand deformity. Distally, the anterior interosseous nerve can be injured, and the median nerve can be damaged at the wrist or compressed within the carpal tunnel.[27]