Introduction

Bone markings are invaluable to the identification of individual bones and bony pieces and aid in the understanding of functional and evolutionary anatomy. They are used by clinicians and surgeons, especially orthopedists, radiologists, forensic scientists, detectives, osteologists, and anatomists. Although the untrained eye may overlook bone markings as contours of the bone, they are not as simple. Bone markings play an important role in human and animal anatomy and physiology. The functionality of bone markings ranges from enabling joints to slide past each other or lock bones in place, providing structural support to muscle and connective tissue, and providing circumferential stabilization and protection to nerves, vessels, and connective tissue. Understanding the importance of bone markings provides a new appreciation and understanding of bony anatomy and its functional relationships with soft tissues.[1][2][3][4][5]

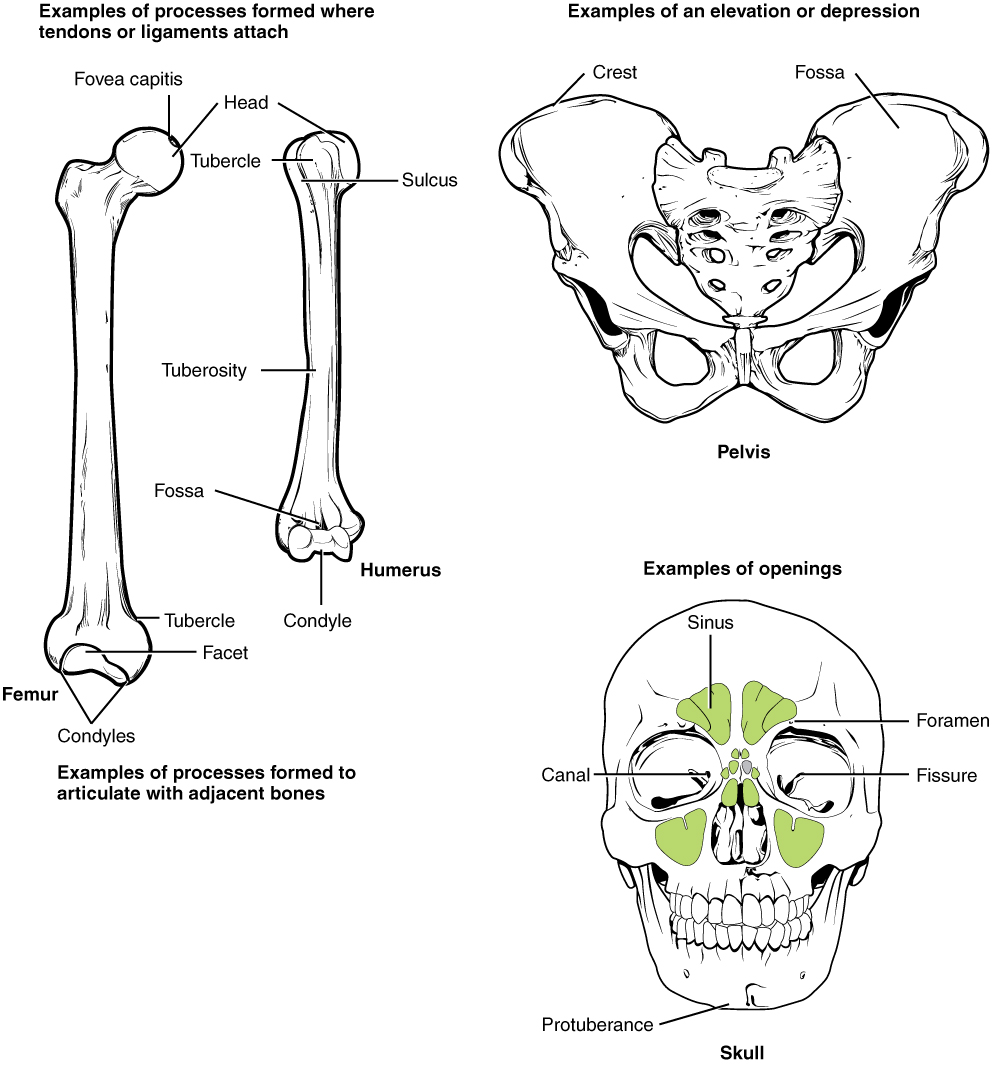

Common Bone Markings

Angles - Sharp bony angulations that may serve as bony or soft tissue attachments but often are used for precise anatomical description. Examples include the superior, inferior, and acromial angles of the scapula and the superior, inferior, lateral angles of the occiput.

Body - This usually refers to the largest, most prominent segment of bone. Examples include the diaphysis or shaft of long bones like the femur and humerus.

Condyle - Refers to a large prominence, which often provides structural support to the overlying hyaline cartilage. It bears the brunt of the force exerted from the joint. Examples include the knee joint (hinge joint), formed by the femoral lateral and medial condyles, and the tibial lateral and medial condyles. Additionally, the occiput has an occipital condyle which articulates with atlas(C1) and accounts for approximately 25 degrees of cervical flexion and extension.

Crest - A raised or prominent part of the edge of a bone. Crests are often the sites where connective tissue attaches muscle to bone. The iliac crest is found on the ilium.

Diaphysis - Refers to the main part of the shaft of a long bone. Long bones, including the femur, humerus, and tibia, all have a shaft.

Epicondyle - A prominence that sits atop of a condyle. The epicondyle attaches muscle and connective tissue to bone, providing support to this musculoskeletal system. Examples include the femoral medial and lateral epicondyles and humeral medial and lateral epicondyles.

Epiphysis - The articulating segment of a bone, usually at the bone's proximal and distal poles. It usually has a larger diameter than the shaft (diaphysis). The epiphysis is critical for bone growth because it sits adjacent to the physeal line, also known as the growth plate.

Facet - A smooth, flat surface that forms a joint with another flat bone or another facet, together creating a gliding joint. Examples can be seen in the facet joints of the vertebrae, which allow for flexion and extension of the spine.

Fissure - An open slit in a bone that usually houses nerves and blood vessels. Examples include superior and inferior orbital fissure.

Foramen - A hole through which nerves and blood vessels pass. Examples include supraorbital foramen, infraorbital foramen, and mental foramen on the cranium.

Fossa - A shallow depression in the bone surface. Here it may receive another articulating bone or act to support brain structures. Examples include trochlear fossa, posterior, middle, and anterior cranial fossa.

Groove - A furrow in the bone surface that runs along the length of a vessel or nerve, providing space to avoid compression by adjacent muscle or external forces. Examples include a radial groove and the groove for the transverse sinus.

Head - A rounded, prominent extension of bone that forms part of a joint. It is separated from the shaft of the bone by the neck. The head is usually covered in hyaline cartilage inside a synovial capsule. It is the main articulating surface with the adjacent bone, forming a "ball-and-socket" joint.

Margin - The edge of any flat bone. It can be used to define a bone's borders accurately. For example, the edge of the temporal bone articulating with the occipital bone is called the occipital margin of the temporal bone. And vice versa, the edge of the occipital bone articulating with the temporal bone is called the temporal margin of the occipital bone.

Meatus - A tube-like channel that extends within the bone, which may provide passage and protection to nerves, vessels, and even sound. Examples include external acoustic meatus and internal auditory meatus.

Neck - The segment between the head and the shaft of a bone. It is often demarcated from the head by the presence of the physeal line in pediatric patients and the physeal scar (physeal line remnant) in adults. It is often separated into the surgical neck and anatomical neck. The anatomical neck, which may represent the old epiphyseal plate, is often demarcated by its attachment to capsular ligaments. The surgical neck is often more distal and is demarcated by the site on the neck that is most commonly fractured. For example, in the humerus, the anatomical neck runs obliquely from the greater tuberosity to just inferior to the humeral head. The surgical neck runs horizontally and a few centimeters distal to the humeral tuberosities.

Notch - A depression in a bone which often, but not always, provides stabilization to an adjacent articulating bone. The articulating bone will slide into and out of the notch, guiding the range of motion of the joint. Examples include the trochlear notch on the ulna, radial notch of the ulna, suprasternal notch, and the mandibular notch.

Ramus - The curved part of a bone that gives structural support to the rest of the bone. Examples include the superior/inferior pubic ramus and ramus of the mandible.

Sinus - A cavity within any organ or tissue. Examples include paranasal sinuses and dural venous sinuses.

Spinous Process - A raised, sharp elevation of bone where muscles and connective tissue attach. It is different than a normal process in that a spinous process is more pronounced.

Trochanter - A large prominence on the side of the bone. Some of the largest muscle groups and most dense connective tissues attach to the trochanter. The most notable examples are the greater and lesser trochanters of the femur.

Tuberosity - A moderate prominence where muscles and connective tissues attach. Its function is similar to that of a trochanter. Examples include the tibial tuberosity, deltoid tuberosity, and ischial tuberosity.

Tubercle - A small, rounded prominence where connective tissues attach. Examples include the greater and lesser tubercle of the humerus.

Structure and Function

The Scapula

The scapula serves as a mobile platform for the upper limb. One can think of it as a massive construction crane with jacks that anchor the cab to the ground. In this metaphor, these are the muscles that attach the scapula to the body. The crane also has a very long arm that is very mobile. In this metaphor, this is the upper limb.

Bony features of the scapula: The scapula has a medial border, a lateral border and a superior border. The inferior pole is located at the point where the medial and lateral borders meet.

The dorsal surface of the scapula contains the prominent spine of the scapula. The trapezius inserts on the superior surface of the spine of the scapula. The deltoid muscle arises from the lateral aspect of the spine of the scapula, as well as the acromion and clavicle. The supraspinous fossa above the spine of the scapula gives origin to the supraspinatus muscle, which inserts on the “S” facet of the greater tubercle of the humerus (see below). The infraspinous fossa below the spine of the scapula gives rise to the infraspinatus muscle, which inserts on the “I” (middle) facet of the greater tubercle of the scapula.

The acromion process of the scapula is located at the lateral end of the spine of the scapula. This process is part of the origin of the deltoid muscle, which is named for the capital Greek delta. The medial border of the scapula gives rise to the insertions of the rhomboid minor and major muscles. The lateral border gives rise to the origins of the teres minor and teres major muscles.

On the anterior surface of the scapula, the prominent coracoid (like a crow’s beak) process is observed. This process gives attachment to the insertions of the pectoralis minor. It gives rise to the origin of the short head of the biceps brachii and coracobrachialis muscles. The subscapular fossa gives rise to the origin of the subscapularis muscle., which inserts on the lesser tubercle of the humerus.

The glenoid fossa of the scapula receives the head of the humerus at the scapula-humeral articulation, in which the platform for the upper limb (scapula) articulates with the head of the humerus (arm).

The Humerus

The humerus is the bone of the arm. At its superior end, one can see the greater and lesser tubercles of the humerus. The greater tubercle is located laterally and has three prominent facets. These are termed the “S”, “I”, and “T” facets. The most superior (“S”) forms the insertion of the supraspinatus muscle, which is a major abductor of the arm at the shoulder. It is the only abductor for the first 15-20 degrees of abduction, but beyond this point the much more powerful deltoid is the major abductor of the arm at the shoulder. The middle (I) facet receives the insertion of the infraspinatus, a lateral rotator of the arm at the shoulder. The lower (T) facet receives the insertion of the teres minor, a lateral rotator of the arm at the shoulder.

The lesser tubercle of the humerus receives the insertion of the subscapularis, a major adductor of the arm at the shoulder. It helps to prevent dislocation of the arm at the shoulder.

The lateral surface of the midshaft of the humerus exhibits the prominent deltoid tuberosity, the site of the insertion of the deltoid. This muscle is a powerful abductor of the arm at the shoulder once the supraspinatus has abducted the first 15-20 degrees. Its anterior fibers serve to rotate the arm medially at the shoulder. The posterior fibers serve to laterally rotate the arm at the shoulder.

The posterior aspect of the middle of the humerus demonstrates the radial spiral groove, between the lateral and medial heads of the triceps brachii. It transmits the radial nerve and the profunda brachii artery.

The inferior aspect of the humerus is marked by the presence of the lateral and medial epicondyles. The lateral supracondylar ridge flows into the lateral epicondyle. It gives rise to the origin of the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus. The lateral epicondyle is a bony prominence that gives origin to the extensor carpi radialis brevis, extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi, and extensor carpi ulnaris.

The olecranon fossa lies on the posterior aspect between the lateral and medial epicondyles. It receives the olecranon process of the ulna at the elbow joint.

The areas between the anterior aspect of the distal humerus is formed by the articulating surfaces of the humerus – the laterally located capitulum (Latin - “little head”) and the trochlea (Greek - pulley).

The Radius

The proximal end of the radius is formed by the head of the radius, which articulates with the capitulum. This arrangement allows the radius to rotate so that the palm is upwards (supination) or downwards (pronation). This gives extra mobility but permits the radius to be dislocated by a sudden jerk of the upper limb (“nursemaid’s elbow” – see below. The radial tuberosity gives insertion of the biceps brachii. The shaft of the radius leads to the large styloid process at its distal end. The brachioradialis muscle inserts on the styloid process of the radius.

The Ulna

The proximal end of the ulna forms the coronoid process, which articulates with the trochlea of the humerus. This articulation is strong, and only permits flexion and extension. The tuberosity of the humerus receives the insertion of the brachialis muscle. This muscle is a pure flexor of the forearm at the elbow. The distally-located head of the ulna articulates with the radius, The radius and ulna articulate with the carpal (Latin carpus = wrist) bones.

The Wrist Joint (Carpus), Metacarpals, and Fingers

The wrist joint articulates with the radius and ulna. There are eight carpal bones, located in two rows. The proximal row has the scaphoid (Latin – like the prow of a ship) located on the lateral aspect articulating with the trapezium in the distal row. The trapezium then articulates with the first metacarpal bone which articulates with the thumb. Passing from lateral to medial on the proximal row, one finds the lunate (Latin - like a moon luna), then the triquetrum (Latin - having three corners), then the rounded pisiform (Latin - pea-shaped). The pisiform can be felt on the anterior aspect of the hand. Put your hand on the rounded bump protruding on the medial side of the hand. When you move your hand, you can confirm that the pisiform moves and therefore is part of the wrist rather than the forearm.

The second row is located distal to the first. Beginning on the side of the thumb, this row is formed by the trapezium (Latin – trapezium – four-sided figure with two sides parallel). This carpal bone articulates with the metacarpal for the thumb and index finger. The second bone in the distal row is the trapezoid (like a trapezium), which then articulates with the large capitate (Latin - chief) bone. Finally, there is the hamate (Latin - hook) bone which has a prominent hook. The space between the pisiform and the hook of the hamate bone is termed Guyon’s canal. It transmits the ulnar nerve. Fracture of the hook of the hamate can damage the ulnar nerve.

There are 14 bones that form the fingers. They are termed phalanges. This word refers to the military formation (phalanx) in which a block of troops would line up behind each other, forming one phalanx. There are three phalanges for all the fingers, but only two for the thumb. The fingers move forwards (flexion) out of the plane of the hand, and move backwards (extension) into the plane of the hand. If the fingers separate, this is termed abduction. If they come back together, this is termed adduction. The metacarpal bones (Latin - after the wrist) connect the carpal (wrist) bones with the fingers. There are five of these – one for each finger. The carpo-metacarpal articulation for the thumb is rotated 90 degrees. If you observe your hand, you will see that the thumb lies out of the plane of the hand. The movements of the thumb are 90 degrees opposite to the articulations of the hand. Thus, one flexes the fingers or extends them in the sagittal plane. But one extends the thumb in the plane of the hand, and moves it back to the hand by flexing it. However, if one brings the thumb out of the plane of the hand, this is termed abduction (Latin – to lead away from). Returning the thumb to the hand is termed adduction. (Latin to lead towards).

Embryology

Although rigid and seemingly stagnant, the bone is an active organ that is constantly remodeling via the action of osteoclasts and osteoblasts, which degrade and build bone, respectively. As such, the contours of the bone will reflect the forces on it, whether they be from adjacent hard or soft tissue. This is described as Wolff's Law, which states that healthy bone will remodel itself with adaptive changes to forces. The bone will remodel its contours to reflect the frequency, distribution, and magnitude of forces.

Articulating features of bones, like facets, condyles, and heads, develop as a result of articulating surfaces between two bones.

Protuberances like crests, trochanters, tuberosities, and tubercles result from traction forces of connective tissue and muscles. The various sizes and shapes of these markings are indicative of the forces that are applied to the bone by these tissues. The wide range of bone markings begins to form early in embryologic development and continues for about 20 years.

Surgical Considerations

Bone markings are significant to physicians and surgeons because they serve as anatomic landmarks that give information about the structures surrounding them. For example, an anesthesiologist will inject just medial and posterior to the ischial spine to achieve a pudendal nerve block. Alternatively, bone markings like the adductor tubercle on the femur can give valuable information about the muscles the surgeon is viewing.[6][7]

Clinical Significance

Nearly all medical providers will use bony landmarks throughout their careers to approximate injection sites, localize the desired soft tissue, or target medical imaging. There are many such examples; however, the following are notable:

- Spinous processes are palpated and used as anatomic guides during epidural steroid injections or lumbar punctures (AKA spinal tap).

- Tibial and femoral condyles are palpated to approximate the menisci sites during the McMurray test, which evaluates the structural integrity of the meniscus.

- Bony landmarks of the elbow are used to orient the operator and locate areas of interest for targeted medical imaging like ultrasound.

Nursemaid’s Elbow

Fracture of the greater tubercle of the humerus results in damage to the insertions of the supraspinatus (“S” facet), infraspinatus (“I” facet), and teres minor (“T”) facet. Loss of the supraspinatus abolishes the ability to initiate abduction of the arm at the shoulder. This should be tested by holding the patient’s arm and having him initiate abduction against resistance. The much more powerful deltoid muscle can abduct the arm at the shoulder once the supraspinatus has begun abduction (15-20 degrees). If one does not test against resistance, the patient may bump his arm enough to appear to be able to abduct the arm completely. Having the patient abduct while the patient’s arm is held at his side makes the deficit due to the supraspinatus obvious. The infraspinatus and teres minor are lateral rotators of the arm, so this will be weakened, but the posterior fibers of the deltoid are much powerful. The other clue is pain upon palpation of the greater tubercle [8][9][8].

Fracture of the lesser tubercle of the humerus will damage the insertion of the subscapularis, a powerful adductor and medial rotator of the arm at the shoulder. This will cause pain which can be worsened upon palpation of the lesser tubercle[10][11][12].

Fracture of the surgical neck of the humerus will damage the axillary nerve, which innervates the deltoid and teres minor. The axillary nerve terminates as the upper lateral cutaneous nerve of the arm, so there will pain and/or anesthesia over this region[13][14].

Lateral epicondylar fracture – damages the radial nerve, which innervates the extensor muscles of the forearm and hand. Injury to the radial nerve gives rise to a wrist drop, in which the patient is unable to extend the hand at the wrist. This is tested by having the forearm flexed in a pronated position. The examiner holds the forearm with his left hand and the dorsum of the hand with his right hand. The patient is then instructed to extend the fingers against resistance[15][14].

Medial epicondylar fracture damages the ulnar nerve, causing loss of the muscles innervated by the ulnar nerve. There is weakness in forearm flexion, producing a radial deviation of the medial side of the wrist. The result is a “claw hand” in which the third and fourth fingers are flexed due to loss of the third and fourth lumbricals, and the interossei. There is a sensory loss in the hand over the fourth finger and half the ring finger (the ulnar nerve territory). Sensation to the dorsal surface of the medial hand is also present due to damage to the dorsal branch of the ulnar nerve[16][17].

Fracture of the hook of the hamate at Guyon’s canal. Guyon’s canal is located between the pisiform bone and the hook of the hamate bone. Fracture of the hook of the hamate causes swelling that can damage the ulnar nerve, which innervates the abductor digiti minimi, flexor digiti minimi, opponens digiti minimi, the third and fourth lumbricals, and the four dorsal interossei, three palmar interossei, and finally the adductor pollicis brevis. Palpation of the pisiform and hook of the hamate bone produces pain. Loss of the adductor pollicis can be tested as follows. Have the patient hold a piece of paper (or the examiner’s index finger) and tell him not to let the paper slip out of his grasp. If the ulnar nerve is injured, the adductor pollicis is not functional, and the patient will be unable to retain the paper. However, the patient will instinctively tend to flex the flexor pollicis longus muscle to hold the paper, and the distal phalanx of the thumb will undergo flexion. This flexion of the thumb is termed Froment’s sign[18][19][20].

Scaphoid fracture – The scaphoid is located in the depths of the anatomical snuffbox formed by the tendons of the abductor pollicis longus and the extensor pollicis longus anteriorly and the tendon of the extensor pollicis longus posteriorly. Fracture of the scaphoid produces pain, tenderness, and bruising over the anatomical snuffbox. Palpation in the depths of the snuffbox causes pain. Unfortunately, it may take a week for the fracture to be demonstrated on a radiograph. The wrist should be splinted to prevent movement of the fractured scaphoid. Allowing the scaphoid to move freely will cause the fractured portion to separate, resulting in a permanent non-union of the fracture, preventing healing[21][22][23].