Continuing Education Activity

Vascular tumors include tufted angiomas, pyogenic granulomas, hemangiomas, and hemangiopericytomas. Vascular malformations include venous, lymphatic, mixed, arteriovenous, or capillary subtypes. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of Kaposi sarcoma, angiosarcoma, and malignant vascular lesions that have a predilection for the skin of the face and neck. It also explains the role of interprofessional team members in collaborating to provide well-coordinated care and enhance outcomes for affected patients.

Objectives:

Describe exam findings consistent with vascular tumors of the face and neck.

Review the differential diagnosis of vascular tumors of the face and neck.

Outline treatment options for vascular tumors of the face and neck.

Explain the importance of collaboration and communication among the interprofessional team in educating HIV-positive patients on Kaposi sarcoma, which can lead to earlier detection and better outcomes for those with this condition.

Introduction

Vascular lesions of the head and neck have historically been difficult to identify and diagnose without a biopsy accurately. In the past, the ability to correctly identify these lesions depended on the experience and the ability to watch the lesion evolve. One of the first advancements made for better classification of these lesions came when vascular lesions were divided into two groups: vascular tumors and vascular malformations. Recently, technological advancement in medical imaging and histological processing has helped practitioners have a better understanding of these lesions. Further subgroups have since then been identified. Vascular tumors include hemangiomas, tufted angiomas, pyogenic granulomas, and hemangiopericytomas. Vascular malformations are further subdivided into the categories of lymphatic, venous, mixed, arteriovenous, or capillary. Treatment and prognosis of these lesions depend on proper identification as interprofessional teams are often needed for appropriate management. This article introduces and discusses malignant vascular lesions appearing on the skin that have a predilection for occurring on the face and neck, Kaposi sarcoma, and angiosarcoma.

Etiology

Kaposi sarcoma is a cutaneous malignancy of lymphatic endothelial cells and believed to have a genetic and viral predisposition. Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) has been well studied to be the cause of Kaposi sarcoma; however, other factors in an individual's health play a role.

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is another type of cutaneous vascular malignancy. The most well-known risk factor is radiation therapy for the treatment of other malignancies. The typical timeline for the occurrence of an angiosarcoma is 5 to 10 years after receiving radiation. Chronic lymphedema also predisposes to cutaneous angiosarcoma, whether it be due to lymphadenectomy, Milroy disease (hereditary lymphedema), or chronic infection. This is known as Stewart-Treves syndrome, or cutaneous lymphangiosarcoma secondary to longstanding lymphedema.[1] Trauma to the skin has also found to be a minor association, mostly because this is the initial event that alerts the patient to their lesion.[2] Other risk factors that have been mentioned in the literature include exposure to arsenic and polyvinyl chloride, as well as previous herpes zoster and vascular malformation sites.[3][4] Most cutaneous angiosarcomas, however, have no association with preexisting lesions.

Epidemiology

Kaposi sarcoma is subdivided into four groups: classic, endemic, immunosuppressed, and AIDS-related (also called epidemic).[5] The classic type is generally seen in Mediterranean males between the ages of 50 to 70. In sharp contrast, the endemic type, classically seen in southern and eastern Africa, is most common in children and can account for up to 50% of all soft tissue tumors of childhood. This type is very aggressive and can progress into a lymphadenopathic form. The immunosuppressed type is straightforward and generally seen in an immunocompromised population, whether it be secondary to medications or organ transplants. Mediterranean males are at a higher risk for developing immunosuppressed Kaposi sarcoma, supporting the thought process that Kaposi sarcoma is somewhat genetically susceptibility. However, the most common type of Kaposi sarcoma is AIDS-related, which is also the most common malignancy associated with AIDS.[6] Kaposi sarcoma is 20 times more common in men who have sex with men than in those who acquired HIV through another vector, for example, transfusion.

Angiosarcomas are rare malignancies consisting of anaplastic vascular or lymphatic cells that invade local structures. Angiosarcomas are very rare, with 1% to 2% of all head and neck sarcomas being angiosarcomas.[7] The most common presentation of an angiosarcoma is cutaneous, and in this review article, it will be referred to as cutaneous angiosarcoma. Head involvement, particularly on the face and scalp, appears to be the most common location of cutaneous angiosarcoma, occurring greater than 50% of the time, especially in older, White males between the ages of 60 and 80 years.[8][9][10] Cutaneous angiosarcoma arises almost exclusively in the context of chronic lymphedema and following radiation therapy. All other instances are idiopathic.[11]

Pathophysiology

Kaposi sarcoma has a viral association with Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus/human herpesvirus 8, a gammaherpesvirus.[12] The pathophysiology involved with the development of Kaposi sarcoma is the reprogramming of the host’s blood endothelial cells to look a lot like lymphatic endothelium by HHV-8. Many genes are upregulated to increase the production of lymphatic vessel endothelial receptor 1 (LYVE1) and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR3), which induces the proliferation of Kaposi sarcoma tumor cells.[13] However, the general understanding is that HHV-8 alone is not enough to cause Kaposi sarcoma, and a degree of immunosuppression in the host is also required, which may be why Kaposi sarcoma is mostly seen in patients with AIDS and a low CD4 count.[14]

Cutaneous angiosarcomas pathophysiology is not as clear-cut as for Kaposi sarcoma. Tumors may arise de novo, or patients may have predisposing factors, such as lymphedema and radiation. A recent study showed a high-level amplification of the MYC gene found in 55% of postirradiation angiosarcoma or chronic lymphedema, but not in primary angiosarcoma.[14] This amplification has been seen in other cutaneous malignancies such as osteosarcomas and epithelioid sarcomas and therefore is associated with unregulated soft-tissue growth.

Histopathology

The histopathology of Kaposi sarcoma is generally divided into two groups: patch-stage and plaque-stage.[15] Patch-stage Kaposi sarcoma is distinguished by thin endothelial cells lining abnormal vessels permeating the dermis. Chronic inflammatory cells, extravasated red blood cells, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages may also be seen on histology, and because these features are inconspicuous, they may lead to misdiagnosis. Plaque-stage Kaposi sarcoma, on the other hand, is characterized by the proliferation of both spindle cells and vessels involving the dermis and subcutis. These lesions may also have chronic inflammatory cells and hemosiderin-laden macrophages residing in the tissue, which may help differentiate Kaposi sarcoma from other iron-free skin pathologies. The classic Kaposi sarcoma lesions do not display marked cellular atypia or increased mitotic figures. Uncommonly, AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma may house opportunistic infections such as Cryptococcus, Mycobacterium, and molluscum contagiosum.[16]

Cutaneous angiosarcoma should always be biopsied if there is any suspicion, due to the gravity of the diagnosis. Even through biopsy, a diagnosis may be difficult because of the degree of cellular undifferentiation seen. Three basic patterns exist, the formation of vascular channels, the formation of sheets of cells, or a completely undifferentiated type. Irregular vascular spaces, malignant endothelial cells forming primeval, serpentine vascular lumens, and spindled appearance may all be seen on histology.[17] However, these features are typically seen in a more high-grade lesion, while low-grade lesions may display low-grade cytology and open vascular lumen. Despite what is seen histologically, there is a consensus that the histological grade and mitotic activity does not affect prognosis in the same way they would at other anatomical regions of the body.[18][19] Because of the difficulty in diagnosing an angiosarcoma based on histology alone, various tumor markers can be used to narrow the diagnosis. These include Ulex europaeus agglutinin, antibody to factor VIII, and CD31 and 34 antigens.

It can sometimes also be difficult to differentiate between Kaposi sarcoma and a low-grade cutaneous angiosarcoma. A dermatopathologist should be consulted in this scenario. Some clues to that point to Kaposi sarcoma are vessels that are slightly more irregular, while angiosarcomas display cellular atypia.[11] In the same way, a high-grade angiosarcoma may primarily appear to be an anaplastic melanoma or an epithelial carcinoma.[20]

History and Physical

One of the difficult aspects of accurately diagnosing Kaposi sarcoma is the different presenting clinical morphologies. The presentation can include and is not limited to, macules, patches, papules, plaques, and nodules, which are purple/red. When occurring on the lower extremities, Kaposi sarcoma has a more classic initial presentation of purples patches. Lesions on the face and neck have a predilection for the nose, eyelids, ears, and oral mucosa, particularly the hard palate. The lesions can have spontaneous rapid growth or may be slow growing. A full review of systems must be performed in anyone with a vascular lesion, as positive fevers, night sweats, and weight loss may be a clue to malignancy. The type of Kaposi sarcoma most likely to present on the head and neck is the AIDS-associated type. The endemic type of Kaposi sarcoma may present with lymphadenopathy of the neck with mucosal involvement.

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is difficult to diagnose clinically due to often having a benign appearance. It has been referred to as “the great mimicker.” Clinically, they appear as violaceous nodules and plaques, bruise-like lesions, and may appear to be hemorrhagic macules and patches. Patients may also present with lesions mimicking hematomas, rosacea, cellulitis, and angioedema.

Evaluation

A punch biopsy is a preferred way to biopsy vascular lesions of the skin. This will help to confirm the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma or cutaneous angiosarcoma. False negatives are possible, and therefore multiple biopsies of the lesion may be needed. If the lesion is thought to be secondary to radiation, the biopsy should be taken away from the edges as the edges may simply show post-irradiation changes.[21] Laboratory tests should be performed, especially a CD4 count in an HIV positive individual, which typically is under 200 cells/mL when Kaposi sarcoma is present. Positive emission topography MRI and CT with contrast have been used at times to detect if larger lesions have invaded local structures. Angiosarcomas appear as irregular, enhancing soft-tissue masses on these modalities.[22]

Treatment / Management

The treatment of Kaposi sarcoma is based on type. Classic Kaposi sarcoma may be surgically excised if the lesion is in-situ without evidence of invasion of local structures. If multiple lesions are present, radiation is the mainstay treatment. If the lesions are recurrent or become extensive, it may be necessary to add chemotherapy to radiation, in addition to surgical intervention. Endemic Kaposi sarcoma is typically treated with radiation and chemotherapy. Immunosuppression-associated Kaposi sarcoma is treated by removing the offending agent, if possible. If that does not resolve the lesion, radiation and chemotherapy are added. AIDS-associated Kaposi sarcoma has many additional modalities used for treatment. Radiation is particularly effective for large, ulcerated lesions. Cryosurgery may also be implemented in 3-week intervals for superficial lesions with a great cosmetic outcome. Vincristine has been injected into lesions with successful regression of the lesions. Last, oral antiretroviral medications, in combination with radiation or oral medications like interferon-alpha, have been shown to be successful. Kaposi sarcoma has even been found to regress spontaneously if appropriate antiretrovirals have been started.[23]

The mainstay of treatment of cutaneous angiosarcoma is a combination of surgical excision with radiation. The literature shows a better outcome when both treatment modalities are used rather than one or the other. Surgery may not be appropriate, though, depending on the location, size, and visibility of the tumor. Radiation therapy, on average, was delivered with megavoltage (Cobalt-60 or higher) photons or elections with a median dose of 60 Gy and a median dose per fraction of 2.0 Gy. This applied to patients who received radiation in addition to surgery or who just received radiation.[24]

Challenges in treatment include achieving negative margins on surgical excision due to the possibility of skin lesions or the inability to visualize the entire malignancy. In some institutions, patients are also offered neoadjuvant taxane-based chemotherapy, though no benefit was seen with the addition of chemotherapy at that institution.[24] However, other institutions experienced a 5-year survival rate of 55% with the addition of taxane-based chemotherapy, surpassing the overall 5-year survival rate as listed below.[25] Despite these results, no prospective randomized studies have been conducted to provide treatment guidelines for the use of chemotherapeutic agents in cutaneous angiosarcoma.[26]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for cutaneous malignant vascular lesions of the head and neck include Kaposi sarcoma and cutaneous angiosarcoma, with the differential diagnosis for those including cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, bacillary angiomatosis, pyogenic granuloma, malignant melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and progressive pigmented purpura.

Surgical Oncology

Usually, surgery is not indicated for the treatment of Kaposi sarcoma, as systemic treatment is required due to the multifocal distribution that is commonly seen.

Radical surgery with the addition of radiation is the gold standard treatment for cutaneous angiosarcoma and is the only treatment modality with possible curative measures.[27] Whenever possible, 1-cm margins should be obtained during surgical excision of a lesion. This may be difficult due to the frequent metastatic invasion of critical structures on the head and neck, and may not always be possible. Surgical excision is usually followed up with a graft or flap reconstruction. One institution found that 77% of patients with cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head and neck were able to achieve negative margins when 1-cm margins were taken.[28]

Radiation Oncology

Kaposi sarcoma is a radiosensitive tumor, and radiation has always played a part in symptom relief as well as local control, particularly of mucosal Kaposi sarcoma lesions. Radiotherapy is a personalized art, where the radiation oncologist takes into account the tumor burden, depth of tumor, and size before deciding the amount of radiation to use. One study reported prescribing extended cutaneous irradiation using 6 to 18 MeV electron beam energy, 200 cGy per fraction, and a total dose of between 24 and 30 Gy given over 2 to 3 weeks for HIV-induced Kaposi sarcoma with good tolerance.[29][30] Another studied showed that a total prescribed dose of 30 Gy split into two doses of 20 Gy and 10 Gy, with two weeks of no radiation between had over a 90% response rate in AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma.[31]

Radiation, in addition to surgical excision, is considered mainstay for the treatment of angiosarcoma, particularly of the head and neck. However, because of the inability to surgically excise every tumor on the head and neck, radiation has been heavily studied and found to be an acceptable monotherapy. Radiation has been found to control the rate of tumor growth, and in some cases, has been found to eradicate the tumor.[32] However, though the area irradiated may be free of malignant cells, metastasis is frequently seen. When involving the scalp, one study showed total scalp irradiation is safe and effective for local tumor control at a total dose of 70 Gy.[33] A different study involving the head and scalp showed radiotherapy delivered at daily fractions of 1.8 to 4.0 Gy at 5 days per week with a total radiation dose ranging from 26 to 71.6 (median 60 Gy) delivered with a 6- to 12-MV electron beam, or a 4-MV X-ray linear accelerator was effective and safe.[34]Many authors have agreed, though, that 60 Gy in 30 fractions with a margin of 3 to 5 cm for treatment of a primary tumor is appropriate.[27][24]

The main side effects of radiation therapy included dry skin, erythema, exudative dermatitis, and rarely skin necrosis.

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

Clinical trials for the treatment of Kaposi sarcoma include the following medications:

- Pilot phase II trial with nelfinavir mesylate

- Phase II trial with recombinant EphB4-HAS fusion protein

- Phase I trial study with pomalidomide and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin hydrochloride

- Phase I/II trial study with Pomalidomide alone

- Pilot Phase II trial with tocilizumab with or without zidovudine and valganciclovir

A pilot study for the use of oraxol as a chemotherapeutic agent for the treatment of cutaneous angiosarcoma is set to begin July 2018.

Treatment Planning

Based on the clinical presentation and the severity of disease, surgical excision, radiation, and chemotherapy can be expected for the treatment of cutaneous vascular malignancies of the head and neck. Surgical excision is typically carried out with at least 1-cm margins. Radiation therapy is delivered at a dose between 30 to 70 Gy depending on the lesion. Chemotherapeutic agents commonly used are the taxel family and vincristine. Please refer to the sections labeled surgical oncology, radiation oncology, and medical oncology for more details regarding treatment planning.

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

Acute toxicity with regards to radiation for the treatment of Kaposi sarcoma is defined as any toxicity that occurs within three months of the radiotherapy, while late toxicity was defined as occurring after three months. Acute toxicity included erythema, skin peeling, and necrosis or gangrene. Late toxicities included changes in skin color, telangiectasia, ulceration, and swelling. This is also applicable to the use of radiation for any treatment of cutaneous malignancies.[29]

The side effect profiles for the chemotherapeutic agents frequently used for the treatment are broad. For the sake of this review, we will focus on the main medications used and their most well-known side effects and toxicities:

- Doxorubicin: dilated cardiomyopathy

- Paclitaxel: peripheral neuropathy

- Docetaxel: constitutional symptoms

Medical Oncology

In patients with classical type Kaposi sarcoma, chemotherapeutic agents such as paclitaxel have been shown to be effective at treating the disease.[35] Systemic chemotherapy is also an option in patients with AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma. One study showed liposomal doxorubicin 15 mg/mg for six cycles over a 4-month period resulted in partial to complete remission of all the patients who took it. Taxol-based chemotherapy was used as salvage therapy.

Continuous chemotherapy with docetaxel and/or paclitaxel for the treatment of cutaneous angiosarcoma has been shown to improve the length of survival, particularly by decreasing the rate of lung metastasis with multifocal tumors. They both have been shown to have both antitumor effects and antiangiogenic effects.[36] Metastatic angiosarcoma lung tumors were found to be successfully treated with docetaxel.[37] Adjuvant doxorubicin-based chemotherapy has also been found to be useful, as it significantly improved the distant recurrence-free time. [38]

Staging

Once a patient is diagnosed with Kaposi sarcoma, the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) system for AIDS-related KS is used to determine the stage. It considers three factors:

- The extent of the tumor: Is the tumor localized (T0) or widespread (T1)?

- The status of the immune system: Is the CD4 T-cell count greater than 150 (I0) or less than 150 (I1)?

- The extent of systemic illness: Is there no systemic infection present (S0), or are there signs of systemic infection (S1)?

The stages that are considered good risk are T0 S0, T1 S0, or T0 S1. The stages that are considered poor risk are T1 S1. Since the introduction of HAART therapy for the treatment of HIV, the status of the immune system has been less important and is often not counted.

The staging of cutaneous angiosarcomas follows the staging used for soft tissue sarcoma, which is the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system. This is based on the following data:

- The extent of the tumor (T)

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N)

- Metastasis to other organ sites (M)

- The grade (G) of the cancer

After a TNM stage has been assigned, further information can be gathered to grade the tumor. The French or FNCLCC system is used to grade soft tissue sarcomas. Different parts of the body have different grading systems. A grading system has not been established for the head and neck in the same fashion that it has been formulated for the trunk, extremities, and retroperitoneal sarcomas.

Prognosis

The prognosis of Kaposi sarcoma is different depending on the types. Of the AIDS-associated Kaposi sarcoma, the prognosis since the introduction of ART has been great. Patients with T0 disease had an overall 5-year survival of 92%, and those with T1 disease had a 5-year survival of 83%.[39] Classic Kaposi sarcoma carries a good prognosis due to its indolent course. A study following a large group of patients for almost five years demonstrated that 24% died of second malignancies, 22% died of other medical conditions, and only 2% died of widespread disease.[40][41][42]

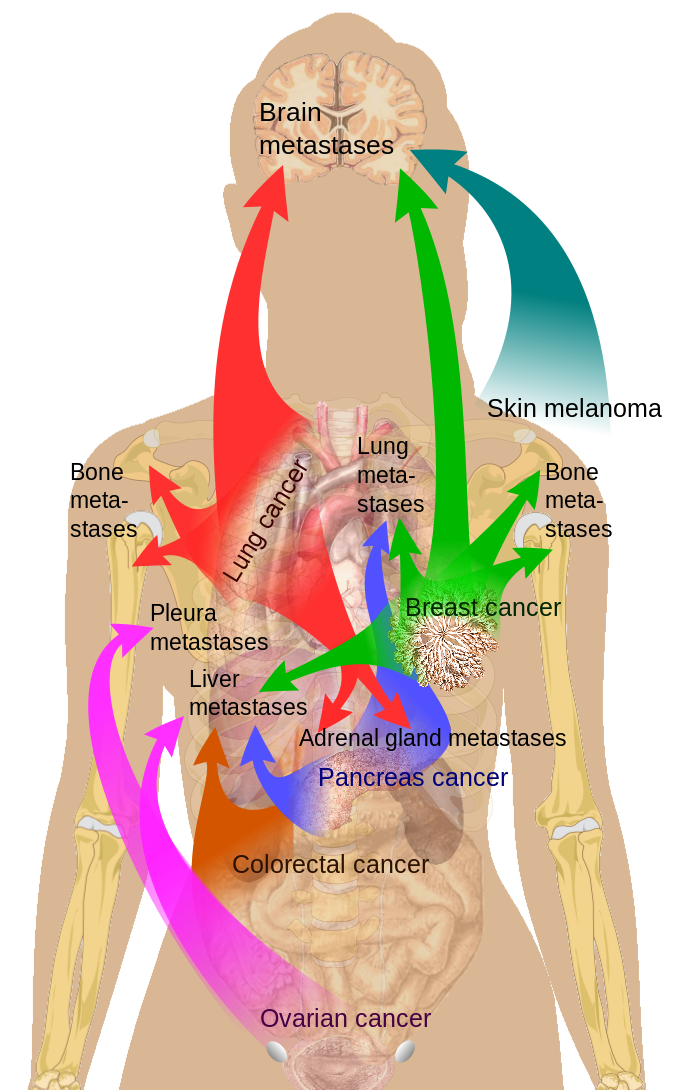

The prognosis of cutaneous angiosarcomas is extremely poor. Metastasis had frequently already occurred at the time of diagnosis, as angiosarcomas are the fastest spreading soft tissue tumors.[19] Angiosarcomas can metastasize to the lungs, liver, lymph nodes, spleen, and brain, with a mean time of survival of 4 months following metastasis, and a 5-year survival rate of 10% to 35%.[43] In 2011, an analysis of 434 cases from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program showed a 5- and 10-year survival rate of 33.6% and 13.8%, respectively.[44] Indicators of poor prognosis include lesion greater than 5 cm, the presence of satellite cutaneous lesions, and the scalp being the location of the primary tumor.[3]

Complications

Complications of all cutaneous vascular malignancies of the head and neck mostly include structural invasion. These tumors can grow on the eyelids, in the nostrils, and on the oral mucosa leading to disruption of the physiologic function of those structures.

Angiosarcomas have far more complications, resulting from frequent hematogenous metastasis to vital organs, particularly the lungs. The ultimate complication is death.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

If surgery is indicated for the removal of a cutaneous vascular malignancy, close follow up will be required with the surgeon who performed the procedure. Sutures on the face are typically left in for 3 to 5 days, while stitches of the scalp are left in for 7 to 10 days. Keeping the wound clean by washing with soap and water, while keeping it moist with petroleum jelly or topical antibiotic cream or ointment is recommended.

Consultations

For any vascular, cutaneous malignancy of the head and neck, interprofessional teams are necessary for the appropriate management of the patient. Patients with Kaposi sarcoma diagnosed through biopsy who are HIV positive may need a referral to an infectious disease specialist for the proper implementation of HAART therapy. These patients, along with patients with other forms of Kaposi sarcoma, may need referrals to radiation oncology and medical oncology for initiation of radiation and chemotherapy depending on the lesion and presentation. After having a confirmed diagnosis of angiosarcoma through biopsy of a lesion, surgery, medical oncology, and radiation oncology should be consulted as soon as possible for the staging of the lesion and the appropriate recommendations regarding surgical excision, radiation, and chemotherapy. Treatment should not be delayed.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Any patient with a new lesion of the head or neck, especially those with HIV, should seek professional medical help to further investigate the lesion. Patients with HIV, who are noncompliant with medication, should be educated on Kaposi sarcoma.

Pearls and Other Issues

Cutaneous vascular malignancies of the head and neck can be incredibly hard to diagnose due to their benign appearance. A full medical history and physical exam should always be performed, especially in patients who are HIV positive. When in doubt, a biopsy of the lesion can help distinguish a benign entity from a malignancy. Due to the deadly nature of cutaneous angiosarcoma and what Kaposi sarcoma involves regarding an HIV positive patient (advanced disease), early diagnosis is key to optimizing long-term survival for patients.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Cutaneous vascular malignancies of the head and neck pose a diagnostic dilemma. Patients will frequently exhibit physical exam findings consistent with benign lesions. Close follow up is warranted when there is any suspicion for a malignant lesion, and a referral to a dermatologist may be indicated. If history and physical exam findings suggest possible HIV infection, patients should be tested. If positive, the patient should follow up closely with an infectious disease specialist.

If a biopsy is performed, an accurate history and physical should be reported to the pathologist. Not only are these malignancies difficult to diagnose clinically, but they also pose a dilemma histologically. Pathologists need to implement various stains for accurate diagnosis, and a thorough history and physical can help narrow it down. Should a cutaneous vascular malignancy such as angiosarcoma be seen on biopsy, the patient should be immediately referred to an oncologist at a tertiary level center with the capability to do surgery and radiation, as surgery with radiation plus or minus chemotherapy is the mainstay treatment for cutaneous angiosarcoma. [Level 3] These patients will require many tiers of care, including interprofessional teams of various physician specialists (medical oncology, radiation oncology, surgery, dermatology, primary care physicians, infectious disease specialists), social workers, pharmacists, specialty trained nurses, nutritionists, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and even home health to provide care that is consistent with improved outcomes.

Should a Kaposi sarcoma be seen on biopsy, the same steps should be taken above, particularly if the patient is HIV negative. If the patient is HIV positive, the most important step is for the patient to follow up with an infectious disease specialist to start the appropriate HAART therapy. Not only is this associated with spontaneous regression of Kaposi sarcoma, but it will also drastically improve the patient’s quality and quantity of life. (Level I) Palliative management of the lesions can be achieved by working with the above physician specialists. If Kaposi sarcoma is seen in the mucosal lining of the mouth, a consult for a gastroenterologist should also be placed to rule out lesions of the gastrointestinal tract, which can lead to internal bleeding.

The outcomes of cutaneous vascular malignancies of the head and neck depend on the lesion found and if the malignancy has metastasized. However, to improve outcomes, a prompt biopsy should be considered if there is any concern about the lesion, and consultation with an interprofessional group of specialists is recommended. Pharmacists are often involved in HAART and chemotherapy, providing patient education and checking for drug-drug interactions. AIDS and oncology nurses participate in care, education, and facilitate communication between the team members.