Introduction

The renal arteries are the only vascular supply to the kidneys. They arise from the lateral aspect of the abdominal aorta, typically at the level of the L1/L2 intervertebral disk, immediately inferior to the origin of the superior mesenteric artery. They are approximately 4 cm to 6 cm long, have a diameter of 5 mm to 6 mm, and run in a lateral and posterior course due to the position of the hilum. They run posterior to the renal vein and enter the renal hilum anterior to the renal pelvis. The renal artery also supplies the adrenal gland and ureter on the ipsilateral side.[1][2][3]

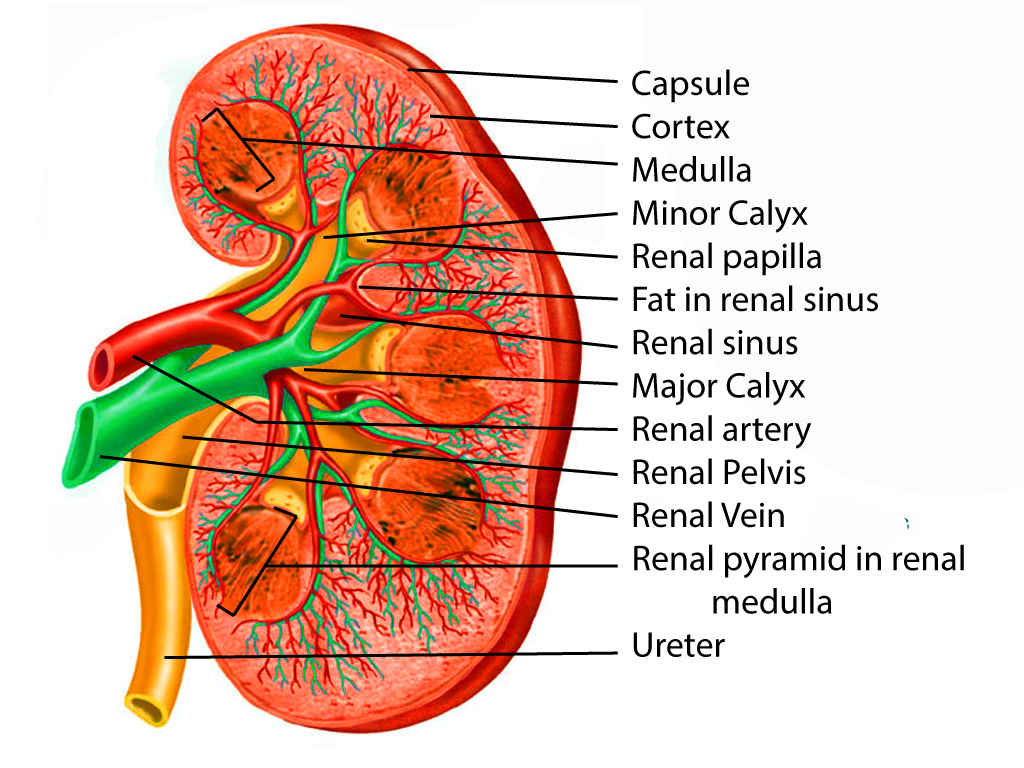

The right renal artery originates from the anterolateral aspect of the aorta and runs in an inferior course behind the inferior vena cava to reach the right kidney, while the left renal artery originates slightly higher and from a more lateral aspect of the aorta, and runs almost horizontally to the left kidney. The renal arteries divide before entering the renal hilum into anterior and posterior divisions, which receive approximately 75% and 25% of the blood, respectively. The anterior division further divides into the upper, middle, lower, and apical segmental arteries while the posterior division forms the posterior segmental artery. Segmental arteries subsequently divide into lobar, interlobar, arcuate, and interlobular arteries before forming the afferent arterioles which feed into the glomerular capillaries.

Structure and Function

Course:

The renal arteries come off the aorta and supply the kidneys. The right renal artery runs an inferior course that courses posterior to the inferior vena cava and right renal vein to reach the hilum of the right kidney. The left renal artery has a much shorter course and runs slightly more inferiorly compared to the right renal artery. The left renal artery has a more horizontal course and can be found just posterior to the left renal vein before it enters the hilum of the left kidney.[1]

Anatomic Relations: Knowledge of the anatomic relations is essential for the surgeons as important structures can suffer an injury during different surgical procedures that require an approach to the renal arteries.

Right Renal Artery: Anteriorly, the proximal portion of the right renal artery is related to inferior vena cava, while the distal portion is related to the shorter right renal vein. These structures separate it from the second part of the duodenum and head of the pancreas. Posteriorly, it is associated with the right renal pelvis and the ureter in its distal section whereas, the right crus of the diaphragm, right psoas major muscle, right sympathetic trunk, cisterna chyli, and body of the 2nd lumbar vertebra in its proximal part.

Left Renal Artery: The left renal vein separates the left renal artery from the body and tail of the pancreas and the splenic vessels. Posteriorly, its proximal part is related to the left crus of the diaphragm, left psoas major muscle, left sympathetic trunk, and the body of the second lumbar vertebra. The distal portion is related to the left renal pelvis and the ureter, posteriorly.

Embryology

The renal system develops through a series of successive phases: the pronephros, mesonephros, and metanephros. The most immature form of the kidney is the pronephros, whereas the most well-developed phase is metanephros, which will persist as the kidney after birth. The metanephros forms at the level of the first sacral vertebra (S1) and the bifurcation of the aorta. Following induction of the metanephric mesenchyme, the inferior segment of the nephric duct will migrate inferiorly and eventually connect with the bladder via the ureters. In the fetus, the ureters transfer urine from the kidneys to the bladder, which then excretes it into the amniotic sac. With the growth of the fetus, the torso expands, and the kidneys migrate upwards and rotate, which also results in an increased length of the ureters.[4]

During its ascent, the kidney gets supplied by several transitory vessels, all originating from the aorta. The definitive renal arteries arise from the lumbar region of the aorta during the ascent while the transitory vessels normally disappear.[4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Both the right and left renal arteries give off several small arteries in the proximal segments. These branches are small and frequently not visible on most imaging studies. The three key branches of the renal artery include the inferior adrenal artery, the capsular artery, and the ureteric artery. Just after the renal artery reaches the hilum, it gives off the ventral and dorsal rami, which further divide into many smaller segmental arteries before they enter the renal parenchyma. These segmental arteries further divide into lobar branches. The afferent arterioles, which come off the interlobular arteries, supply the glomeruli.[1]

Nerves

The kidneys are surrounded by the renal plexus, whose fibers course along with the renal artery on each side. There is also input from the sympathetic nervous system, which can cause vasoconstriction and reduce blood flow in the renal vessels. The kidneys also receive parasympathetic nerve innervation via the vagus nerve — the sensory output from the kidneys gets transmitted to the spinal cord at the T10-T11 level. When the kidney is inflamed, the affected individual usually feels the referred pain along the flank.[1]

Muscles

Both kidneys are retroperitoneal structures on either side of the vertebral column. The right kidney is located slightly lower than the left kidney because of the liver. Each kidney is about three vertebrae in length. Both adrenal glands are superior to the kidneys within the renal (Gerota's) fascia. The left and right kidney are on top of the psoas major and quadratus lumborum muscles.[1]

Physiologic Variants

In at least thirty percent of the population, one can find accessory renal arteries. In rare cases, there are aberrant renal arteries that do not enter the renal hilum but the renal capsule. In about ten percent of the population, one will observe the early branching of the renal arteries. This early-branching typically occurs 15 mm to 20 mm from the renal hilum; this is vital to know when performing a kidney transplant.[5][6]

Surgical Considerations

The renal arteries can be involved in many surgical disorders like renal artery aneurysms, renal artery stenosis, renal artery dissection, and fibromuscular dysplasia. The urologist must be particularly aware of the renal arterial anatomy when involved in renal surgery, particularly transplantation.[1]

Clinical Significance

Variations are common, with over 30% having more than one artery supplying a kidney. These may arise over an extensive range (T11-L4) and often from the aorta or iliac arteries. The majority of these enter the kidney at the renal hilum, although direct entry via the renal cortex also occurs. Accessory arteries that supply the lower pole of the kidney have been shown to obstruct the ureteropelvic junction. Ectopic kidneys are even more likely to have more than one renal artery, and their origins may arise from the celiac, the superior mesenteric artery, or the iliac artery.[1]

The segmental arteries do not contain a collateral system, and as such, ligation or occlusion of these arteries results in ischemia and infarction in the downstream segment of the kidney. The relatively avascular plane of Brodel is useful surgically to access the pelvicalyceal system. Its position is between anterior and posterior segmental arteries in the posterolateral convex margin of the kidney.[7][8][1][8]

Other Issues

Renal artery stenosis is a common cause of renovascular hypertension. In elderly individuals, the usual etiology of renal artery stenosis is atherosclerotic disease. As the lumen of the artery narrows, the renal blood flow drops, and this compromises perfusion of the kidney. Patients with renal artery stenosis may present with azotemia, abdominal bruit, and worsening of hypertension. Sometimes acute renal failure can be precipitated by starting the patient on ACE inhibitors. Unfortunately, the treatment of renal artery stenosis with angioplasty and stenting may not always result in the recovery of renal function.[9]