Definition/Introduction

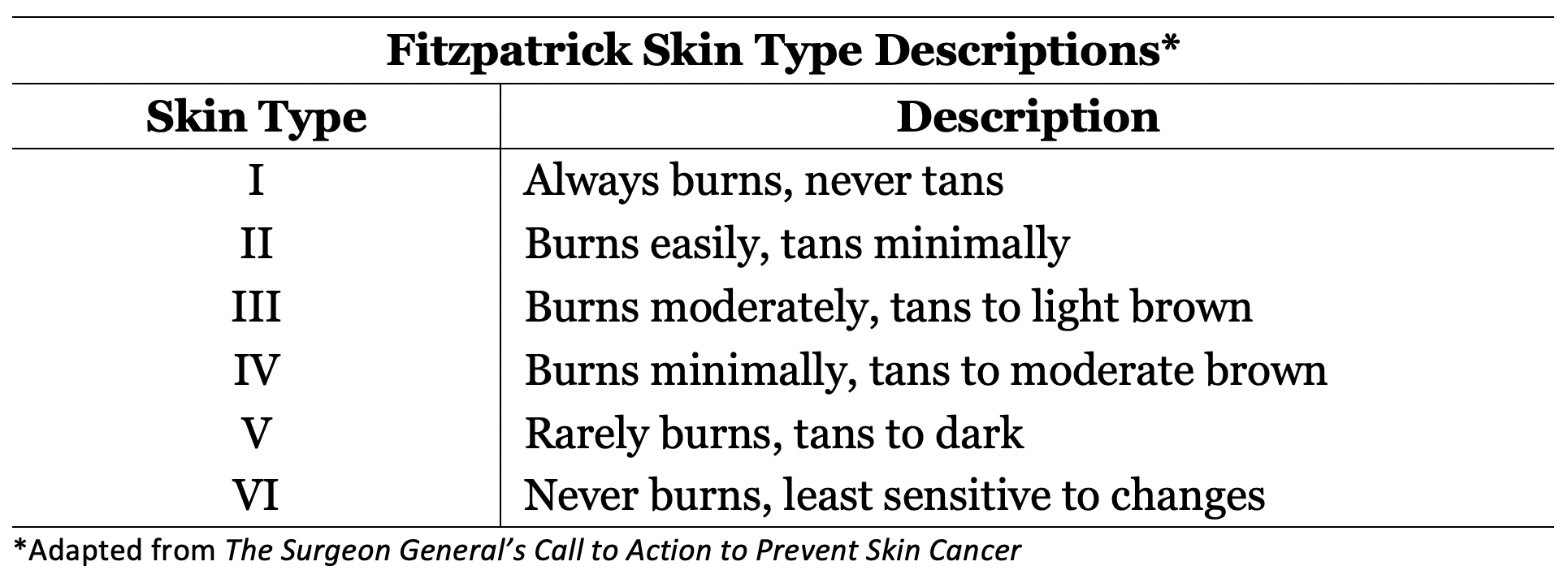

First described by Thomas B. Fitzpatrick in 1972, the Fitzpatrick skin phototypes were developed based on an individual's skin color and their tendency to burn or tan when exposed to sunlight. More specifically, classification was based on a patient's responses to the following questions regarding their skin's reaction to a 45-60 minute, early summer, noon sun exposure in northern latitudes (20-45 degrees): "how painful is your sunburn?" and "how much tan will you develop in a week?" Initially enumerated as skin types I through IV to classify patients with white skin, the Fitzpatrick phototype classification scale was later modified to include types V and VI for persons with darker skin.[1] Generally, a lower Fitzpatrick skin type classification indicates skin that burns more easily than it tans, while a higher Fitzpatrick skin type indicates the opposite (Table 1). The most common skin type in the United States is type III (48%), with types I and II comprising the second largest group (35% in total).[2]

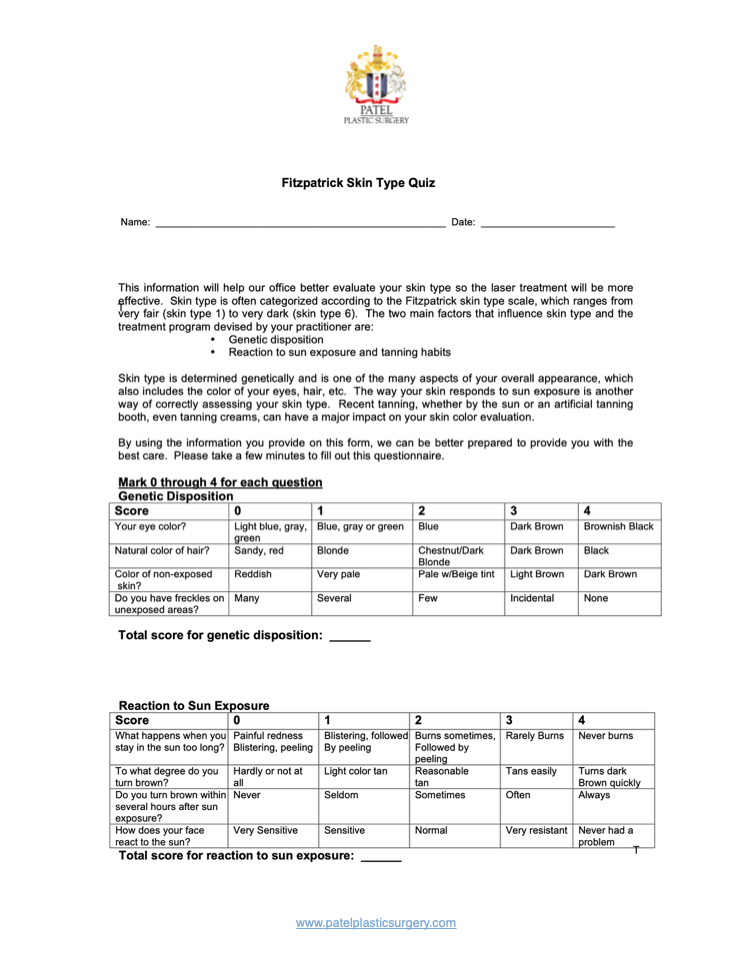

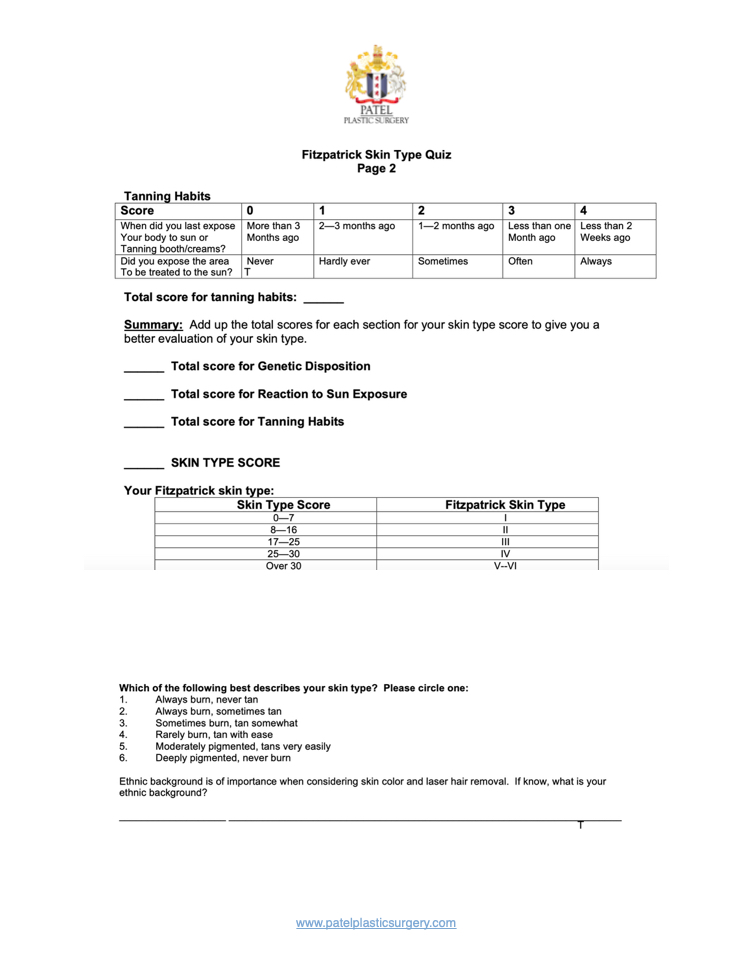

By nature of the criteria, Fitzpatrick's skin type classifications are subjective; however, use of the scale has proven valuable as a diagnostic and therapeutic evaluation tool for many situations. Specifically, these classifications are commonly employed to estimate dosages of particular ultraviolet B (UVB), psoralen with ultraviolet A (PUVA), and laser treatments, as well as to predict skin cancer risk and guide sun protection advice.[3] Though widely used throughout dermatology, plastic surgery, surgical oncology, and other specialties, the Fitzpatrick skin types are not without controversy. Current questions regarding the objective determination, accuracy of self-reporting, and effectiveness in ethnic skin are all major issues of concern with Fitzpatrick skin types.

Issues of Concern

Objective Determination of Fitzpatrick Skin Types

Given the relative ease of implementation of Fitzpatrick skin typing, it is understandable why this classification system has been so widely applied. However, numerous studies have criticized this system scientifically, and validated objective alternatives have been sought, to achieve a similar outcome of predicting ultraviolet (UV) sensitivity.[4] Methods including the Wood’s lamp for quantification of cutaneous eumelanin and pheomelanin have been implemented; however, both have been unsuccessful in differentiating Fitzpatrick skin types higher than level II.[4]

Currently, spectrophotometers are the primary tool in which melanin density in the epidermis can be estimated and implemented in evaluating the accuracy of self-reported skin types.[4] Spectrophotometers are able to distinguish darkening caused by increased melanin from erythema as a result of inflammation or increased hemoglobin, allowing for a more reliable estimation of the true Fitzpatrick skin type.[5] Spectrophotometers have also been used to distinguish constitutive skin color (baseline skin color in body areas not exposed to light) from facultative skin color (skin color in body areas where light-induced pigmentation changes are seen).[4] Specifically, all 6 Fitzpatrick skin types can be discerned by using a reflectance spectrophotometer along the 450 to 615 nm wavelengths.[4] Unfortunately, this tool is not perfect, and the high costs of both personnel and equipment may prevent the widespread adoption of its use.

Inconsistencies with Self-Reporting and Ethnic Skin

It is important to highlight that the Fitzpatrick skin type is a classification intended to reflect sun sensitivity and not a proxy for racial or phenotypic features. The description of the skin by color – white, brown, black – was meant to denote complexion rather than a self-identification of ethnic origin.[6] For example, a cross-sectional survey of an ethnically diverse population showed self-reported pigmentary phenotypes and race were significant but incomplete predictors of Fitzpatrick skin types.[7]

The difficulty in assessing ethnic skin with the current Fitzpatrick skin type system can be traced to the origin skin types V and VI. When these additional types were created in 1988, the initial intention was to place all black individuals into the type VI category. However, people with mixed heritage or races who identify as black often self-report in a variety of categories, ranging from type IV to type VI.[8] Though the reasons for this are multifaceted, the concept of labeling one’s skin reaction to the sun as tanning or burning lacks reliability, as these words have different meanings to different people. Specifically, participants with a skin of color have been shown not to report painful burns or tanning, or simply not understand the meaning of tanning.[8][9] The functionality of Fitzpatrick skin typing in ethnic skin is also under question. In a population-based study of 2691 participants, this classification system correlated with sun sensitivity in non-Hispanic white and Hispanic participants, but not black participants.[2] In response, multiple scales limited to single ethnic groups have been created, including a Japanese Skin Type scale by Kawada and a scale for individuals of African descent by Willis and Earles, in an attempt to more accurately classify the nuances between ethnic skin.[10]

Laser Therapy in Ethnic Skin

Structural and functional differences between darkly pigmented and lightly pigmented skin are important considerations when performing laser or light-based procedures. In general, darker skin types possess increased epidermal melanin, larger and more widely distributed melanosomes, and reactive fibroblasts.[11] Higher numbered Fitzpatrick skin types are, therefore, associated with these biological characteristics, leading to increased melanin content and epidermal distribution. Increased concentrations of melanin allows for greater protection against ultraviolet radiation, leading to less marked and delayed signs of photoaging.[12]

There are a number of factors to consider when treating individuals with Fitzpatrick skin types IV through VI. Melanin in the epidermis acts as a chromophore, absorbing more laser energy and increasing the risk of adverse events from epidermal injury in those with darkly pigmented skin. To circumvent this risk, longer wavelength lasers are recommended. Deeper penetration of the laser allows for an increased ratio of the temperature of the hair bulb to the temperature of the epidermis, leading to follicular destruction with little epidermal damage.[13] Similarly, lower fluences and longer pulse durations (laser hair removal) or lower treatment densities (laser resurfacing) are suggested for darker-skinned individuals to decrease the risk of thermal injury to the epidermis.[13] Pre- and post-treatment with bleaching agents (for example, hydroquinone cream) has been shown to reduce the risk of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, especially after laser resurfacing.[14] Cooling of the epidermis at pre- or post-treatment times can also prevent pigmentary abnormalities, with the most common modalities involving contact or cryogen spray cooling.

With regards to laser or light procedures, the risk of post-procedural hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation is greater in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV through VI. In general, dyschromia is one of the most common reasons why individuals with skin of color visit dermatologists, stemming from their tendency for injury or inflammation to alter pigment production.[15] In addition to the aforementioned recommendations, classification systems such as the Laser Ethnicity Scale have been designed to better predict healing efficacy and times in patients undergoing laser procedures.[16]

Clinical Significance

Fitzpatrick skin types have long been the favored method of classifying an individual’s skin color based on their specific reactions to sun exposure. Clinically, these designations have been employed to estimate dosages, assess cancer risk, or guide counseling (Figures 1 & 2). However, this system has been recognized as ineffectual in certain populations, especially those with darker, non-Caucasian ethnic skin. These individuals are at greater risk of post-procedural pigmentary and scarring-related adverse effects. Thus the accurate determination of Fitzpatrick skin types has important therapeutic consequences. Numerous attempts to create an objective determination of an individual’s skin type have been made; while none are yet considered a gold standard, reflectance spectrophotometers constitute an efficient and noninvasive alternative with a proven record of success.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

While the determination of Fitzpatrick skin types is almost always done by a physician, the administration of laser treatments is a process that may involve many healthcare workers. Physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, nurses, and medical assistants are all involved with laser treatments, and an interprofessional team approach is essential to prevent and/or mitigate pre-, intra-, and post-treatment complications. A detailed education regarding side effects, careful management of expectations, and thorough counseling about results are all essential interprofessional team interventions that will improve outcomes for patients of any Fitzpatrick skin type.[Level 5]