Continuing Education Activity

The management of infectious colitis is complex, and new approaches have been introduced; the basic and clinical aspects of infectious colitis must be clearly defined to achieve satisfactory outcomes. This activity reviews infectious colitis and focuses on the etiology, epidemiology, pathophysiology, evaluation, management, and complications of infectious colitis, and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in improving healthcare outcomes.

Objectives:

Identify the etiology and along with accompanying risk factors for infectious colitis.

Assess the pathophysiology of infectious colitis.

Evaluate patients for infectious colitis.

Determine the management options for infectious colitis, in collaboration with the interprofessional team.

Introduction

Colonic infection by bacteria, viruses, or parasites results in an inflammatory type of diarrhea, accounting for most cases presenting with acute diarrhea. These patients present with purulent, bloody, and mucoid loose bowel motions, fever, tenesmus, and abdominal pain. Common bacteria causing bacterial colitis include Campylobacter jejuni (C. jejuni), Salmonella, Shigella, Escherichia coli (E. coli), Yersinia enterocolitica, Clostridioides (formerly Clostridium) difficile (C. diff), and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Common causes of viral colitis include Norovirus, Rotavirus, Adenovirus, and Cytomegalovirus. Parasitic infestation, such as Entamoeba histolytica, a protozoan parasite, is capable of invading the colonic mucosa and causing colitis. Sexually transmitted infection affecting the rectum merits consideration during assessment. These diseases can occur in patients with HIV infection and men who have sex with men and may include Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Herpes simplex virus (HSV), and Treponema pallidum.

Patients present with rectal symptoms that mimic inflammatory bowel disease, including rectal pain, tenesmus, bloody mucoid discharge, and urgency. Detailed medical history and identification of specific associated risks are essential in establishing the diagnosis. Stool microscopy culture and endoscopy are crucial to the diagnosis. However, stool culture helps diagnose less than 50% of patients with bacterial colitis, and endoscopic examinations usually reveal nonspecific pathological changes. Therefore, an approach is needed to evaluate and diagnose the cause of colitis and exclude non-infectious causes. This activity discusses current strategies to diagnose and manage infectious colitis, how to make a high index of suspicion based on clinical presentation, and how to use investigation methods to reach a final diagnosis. The etiology, epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, evaluation, differential diagnosis, complications, and management of patients with infectious colitis are also reviewed.

Etiology

Infectious colitis may result from infection with:

- Bacterial infections: Including C. jejuni, Salmonella, Shigella, Escherichia coli (including the subgroups enterotoxigenic E. coli, enteropathogenic E. coli, enterohemorrhagic E. coli, enteroinvasive E. coli, enteroaggregative E. coli), Yersinia enterocolitica, C. diff, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

- Viral infections: Norovirus, Rotavirus, Adenovirus, and Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

- Parasitic infections: Such as Entamoeba histolytica (which causes amoebic colitis)

- Sexually transmitted infections: Particularly infections affecting the rectum in patients with HIV infection and men who have sex with men, including Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis (which causes lymphogranuloma venereum), Herpes simplex 1 and 2, and Treponema pallidum (which causes syphilis).

Enterotoxigenic E. coli is the leading cause of traveler’s diarrhea. Enteroaggregative E. coli can cause traveler’s diarrhea, but it is not the leading cause. Enterohemorrhagic E. coli has 2 main serotypes, E. coli O157:H7, and non-O157:H7; the natural reservoirs of both serotypes are cows. Therefore, the infection is related to consuming inadequately cooked beef or contaminated milk or vegetables. They are responsible for outbreaks in developed countries.[1]

Two of these subgroups cause nonbloody diarrhea: enterotoxigenic E. coli and enteroaggregative E. coli; both produce enterotoxins that induce chloride and water secretion and inhibit their absorption. However, enterohemorrhagic E. coli (both strains E coli O157:H7 and non-O157:H7) causes bloody diarrhea and produces Shiga-like toxins, resulting in a clinical picture similar to Shigella dysenteriae infection.[2]

Both enteropathogenic E. coli and enteroinvasive E. coli do not produce toxins. Enteropathogenic E. coli is responsible for outbreaks, particularly in children under 2 years of age. In contrast, enteroinvasive E. coli causes acute self-limited colitis and is responsible for outbreaks mainly in developing countries. However, the 2014 outbreaks in Nottingham, England, highlight the need for its consideration as a potential pathogen in European foodborne outbreaks.[3]

Children (in daycare centers), elderly (in nursing homes), and immunocompromised individuals are susceptible to these infections (see Image. Radiograph of an Infant With Necrotizing Enterocolitis). The usual modes of infection are the fecal-oral route, animal host, and ingestion of contaminated food and water. Food and water contamination with pathogenic bacteria may cause large outbreaks of diseases.

Epidemiology

Bacterial Colitis

Bacterial colitis accounts for up to 47% of cases of acute diarrhea.[4] C. jejuni is the number one bacterial cause of diarrheal illness worldwide, with an estimated prevalence of 25 to 30 per 100,000 population. For Salmonella infection, an estimated 1.2 million annual cases of nontyphoidal salmonellosis occurred in the United States.

Shigellosis

Shigellosis incidence worldwide is reported to be approximately 165 million cases, but mortality has decreased in the last 3 decades because of improvements in laboratory diagnosis and treatment. In the United States, estimates are approximately 500000 cases per year, with 38 to 45 deaths.[5]

Yersinia Enterocolitica

Yersinia enterocolitica colitis commonly presents in young children in the winter. In the United States, the estimates are 1 case per 100,000 individuals each year.

C. Diff

C. diff infection in hospitalized adults in the United States increased from 4.5 cases per 1000 discharges in 2001 to 8.2 cases in 2010 and a mortality rate of 7%.[6] Another study from the United States on Clostridium infection estimated 500,000 cases in 2011, with 83,000 recurrences and 29,300 deaths.

Mycobacterium Tuberculosis

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the third most common site of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, accounting for 12.8% of all cases under this category.[7] The recurrence of tuberculosis in developing countries parallels the AIDS epidemic distribution closely.[8] Other factors for increasing rates of tuberculosis in many developed countries are related to the migrant population, deterioration in social conditions, cutbacks in public health surveillance services, and increased prevalence of immune-suppressed individuals (AIDS, those receiving biological agents in diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease).[9]

Amebiasis

Amebiasis ranks as the second leading cause of death due to protozoan infection after malaria, Chagas disease, and leishmaniasis.[10]

CMV

The prevalence of CMV infection in percent colitis ranges from 21% to 34%.[11] CMV reactivation in patients with severe ulcerative colitis has a reported prevalence of 4.5% to 16.6% and as high as 25% in patients requiring colectomy for severe colitis.

Infectious Proctitis

Infectious proctitis among HIV-positive and HIV-negative men varied and in a recent study was as follows: chlamydia (23% versus 22%, respectively), gonorrhea (13% versus 11%), HSV-1 (14% versus 6%), and HSV-2 (22% versus 12%), lymphogranuloma venereum (8% versus 0.7%), more than 1 infection (18% versus 9%). Approximately 32% of HSV proctitis had external anal ulcerations.[12]

Pathophysiology

C. Jejuni

Infection with C. jejuni is caused by orally ingested contaminated food or water. Several factors influence infections, including the dose of bacteria ingested, the virulence of organisms, and the immunity of the host. The median incubation period is 2 to 4 days. C. jejuni multiplies in the bile, invades the epithelial layers, and travels to the lamina propria, producing a diffuse, bloody, edematous enteritis.

Pseudomembranous Colitis

Pseudomembranous colitis is caused by toxin-producing C. diff. The disease develops due to altered normal microflora (usually by antibiotic therapy such as cephalosporin and beta-lactam antibiotics) that enables overgrowth and colonization of the intestine by C. diff and production of its toxins.[13]

E. Coli

Enterotoxigenic E. coli

Enterotoxigenic E. coli produces heat-labile (HL) and heat-stable (ST) toxins. The HL toxins activate adenyl cyclase in enterocytes, resulting in increased cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) stimulation of chloride secretion and inhibition of absorption. The ST toxins bind to guanylate cyclase, resulting in increased cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) and effects on cellular transporters similar to those caused by HL toxins, resulting in secretory noninflammatory diarrhea (this explains the limited histopathological changes in this infection).[14]

Enteropathogenic E. coli

Enteropathogenic E. coli can produce proteins for "attaching" and "effacing" (A/E) lesions, which enable the bacteria to get tightly attached to the enterocyte's apical membranes and cause effacement or loss of the microvilli. As stated earlier, enteropathogenic E. coli does not produce toxins, and their underlying mechanism for causing diarrhea is by attaching and effacing lesions.[15]

Enterohemorrhagic E. coli

Enterohemorrhagic E. coli, including its serotypes, E. coli O157:H7 and non-O157:H7, produce Shiga-like toxins similar to Shigella dysenteriae infection. However, E. coli O157:H7 strains are more likely to cause outbreaks than non-O157:H7 serotypes. They produce bloody diarrhea and are responsible for the development of hemolytic-uremic syndrome and ischemic colitis.[16]

Enteroinvasive E. coli

Enteroinvasive E. coli does not produce toxins; it invades enterocytes and causes self-limited colitis. The exact details of its pathogenetic mechanisms are still not fully understood.

Enteroaggregative E. coli

Enteroaggregative E. coli produces enterotoxins related to Shigella enterotoxins and ST toxins of enterotoxigenic E. coli. It attaches itself to enterocytes via adherence fimbriae.

Mycobacterium Tuberculosis

Immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis undergoes mediation via T-cells, resulting in macrophage stimulation that kills the bacteria. Reactivation of infection or re-exposure to the bacillus in a sensitized individual, as is the case in most Mycobacterium tuberculosis colitis cases, resulting in rapid defense reactions and increased tissue necrosis accompanied by loss of T-cell immunity (tuberculin test in these patients becomes negative although used to be previously positive, which is consistent with fading T-cell protection).[17]

CMV

Primary CMV infection in immunocompetent individuals is usually asymptomatic. However, patients whose immune response is compromised develop symptoms in different body organs, including CMV colitis.

Entamoeba Histolytica

Research concerning genetics and molecular sciences of Entamoeba histolytica have brought new understanding about mechanisms by which the parasite imposes invasive abilities and pathological lesions in the colon and extracolonic organs. Host factors predisposing to infection are also under research.[17]

Histopathology

No significant differences appear in histological biopsies taken from the rectum of patients with different bacterial infections. However, the absence of crypt architecture distortion or basal plasmacytosis helps differentiate acute infectious colitis from chronic inflammation caused by inflammatory bowel disease.

E. Coli

Infection with E. coli O157:H7 may show changes similar to ischemic colitis (small atrophic crypts, hyalinized lamina propria, and fibrin thrombi). Colonic histopathological changes are limited in enterotoxigenic E. coli, enteroinvasive E. coli, and enteroaggregative E. coli infections.

Yersinia Enterocolitica

Yersinia enterocolitica shows inflammatory changes, ulcerations in the cecum and terminal ileum areas, hyperplasia of Peyer patches, microabscesses, and granulomas. (This condition requires differentiation from Crohn disease and Mycobacterium tuberculosis involving the terminal ileum/caecum area.)

Mycobacterium Tuberculosis

In Mycobacterium tuberculosis, characteristic granulomas with central caseation are present; tubercle bacilli are identifiable with acid-fast stains.[18]

CMV

The diagnosis of CMV colitis requires histological examination of biopsy tissues taken from the ulcer edge or base. Patients with punched-out ulcers are associated with increased inclusion bodies on histology [Yang H et al 2017]. Colonic mucosal biopsies stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) may reveal the typical inclusion associated with CMV colitis, "owl eye appearance" inclusion bodies, which are highly specific for CMV. However, H&E staining has low sensitivity compared to immunohistochemistry, considered the gold standard for diagnosing CMV colitis.[19]

Syphilitic Proctitis

The histological features of biopsies taken from the rectum are nonspecific and cannot differentiate syphilitic proctitis and lymphogranuloma venereum. Laboratory tests, including serology and PCR, are essential in making such differentiation.

History and Physical

Detailed medical history and identification of exposure risks are helpful in the diagnosis. It is essential to mention here that individuals with sickle cell anemia, hemolytic anemia, immunosuppression (corticosteroids, chemotherapy, and AIDS), and extremity of age are at a higher risk of Salmonella infection. Patients with bacterial colitis present with nonspecific symptoms, including diarrhea, fever, tenesmus, and abdominal pain. Patients with Yersinia enterocolitica infection may present a syndrome indistinguishable from acute appendicitis (mesenteric adenitis, mild fever, and ileocecal tenderness).

C. Diff

The incidence of C. diff is higher in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, particularly ulcerative colitis. Any antibiotic can trigger the disease, but the most common antibiotics responsible are cephalosporins, clindamycin, carbapenems, trimethoprim, sulfonamides, fluoroquinolone, and penicillin combinations.[13]

Mycobacterial Tuberculosis

Patients with Mycobacterial tuberculosis may present with abdominal pain, blood per rectum, fever, sweating, tiredness, and pallor. They may give a past medical history of the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. They may have abdominal tenderness in the right iliac fossa (the ileocecal area is the most commonly involved site in intestinal tuberculosis).[18]

Viral Colitis

Viral colitis (Norovirus, Rotavirus, and Adenovirus) is common in infants and young children. Affected patients present with nausea, vomiting, watery diarrhea, and abdominal pain. CMV infection is frequently symptomatic in immune-competent patients. Again, symptoms are usually nonspecific, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, malaise, rectal bleeding, and weight loss. However, hematochezia and diarrhea are the most frequent symptoms. Based on clinical presentation, it is difficult to distinguish between ulcerative colitis and CMV colitis.[14]

Amoebic Colitis

Amoebic colitis usually presents with diarrhea, mucoid discharge, hematochezia, tenesmus, and abdominal bloating. Contaminated water supplies and poor sanitation are often the cases for traveling overseas to endemic areas and increased risk of fecal-oral transmission of amebas.

Sexually Transmitted Infectious Colitis

Patients with colitis associated with sexually transmitted infection present with anorectal pain, with a purulent, mucoid, or bloody discharge, tenesmus, or urgency. The sexual history is vital in evaluating these patients.

Evaluation

Diagnosis of colitis centers on clinical findings, laboratory tests, endoscopy, and biopsy. Endoscopy and biopsy should not be the primary investigations; they may be necessary after a critical evaluation of the patient's condition and the results from the initial examination.

Because infection is a common colitis etiology and can produce clinical presentations indistinguishable from inflammatory bowel disease, microbiological studies and cultures for bacterial and parasitic infestations should be the initial investigations. Laboratory tests should be ordered, including complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), arterial blood gases, activated partial thromboplastin time, serum albumin, total protein, blood urea, creatinine, and electrolytes. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based molecular methods (PCR-based multiplex gastrointestinal pathogens) can help rapidly identify Salmonella, Shigella, and Yersinia investigations from primary stool samples. Abdominal and pelvis CT scans, colonoscopy, tissue biopsies, fecal cultures (multiple specimens), and antimicrobial susceptibility testing should help differentiate infectious from noninfectious colitis causes and guide treatment.[15]

Recently, multidetector CT scans of the abdomen were used to differentiate between inflammatory bowel disease and acute colitis related to bacterial infection. The 5 signs described to diagnose bacterial colitis are (1) continuous distribution, (2) empty colon, (3) absence of fat stranding, (4) absence of a "comb" sign, and (5) absence of enlarged lymph nodes.[16]

Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Colitis

The diagnosis of active Mycobacterium tuberculosis colitis focuses on clinical presentation, clinical examination, and laboratory investigations. A complete blood count may reveal low hemoglobin, leukocytosis, and moderately elevated ESR. Chest X-ray may reveal fibrotic changes, cavitation, or an old scar of pulmonary tuberculosis; an abdominal roentgenogram may reveal a prominent large bowel. Abdominal and pelvis CT scans may show diffuse thickening of the colonic wall, especially of the terminal ileum and the cecum. A colonoscopy usually shows diffuse ulceration throughout the colon, from the rectum to the cecum. Histopathological biopsies taken from the cecum show caseating granuloma and chronic inflammatory cells. A Mantoux skin test (tuberculin test) is usually requested. This test does not measure immunity to tuberculosis but the degree of hypersensitivity to tuberculin. The results must be interpreted carefully, considering the patient's medical risk factors. Usually, the Mantoux test becomes negative in these patients after being previously positive, indicating the fading of resistance to the organism.[17] PCR testing and cultures of intestinal fluid for bacterial species and acid-fast bacillus are requested.

CMV Colitis

Diagnosis of CMV colitis uses clinical findings, laboratory tests, and endoscopic findings. Endoscopy and tissue CMV-specific immunohistochemistry (IHC) and or PCR CMV DNA quantification are needed to confirm the diagnosis [20].

Amoebic Colitis

In amoebic colitis, rectosigmoid involvement may present on colonoscopy; however, the cecum is the most commonly involved site, followed by the ascending colon (showing colonic inflammation, erythema, oedematous mucosa, erosions, white or yellow exudates, and ulcerations). The presence of amoebic trophozoites on histopathological examination or intestinal fluid cultures is important in the diagnosis. Serum E. histolytica antibody examination and antibody titer greater than 1:128 is considered positive.[17][10]

Sexually transmitted infectious colitis

For patients with suspected sexually transmitted infections of the rectum, histological features of biopsies taken are non-specific and cannot differentiate syphilitic proctitis and lymphogranuloma venereum. Laboratory tests are usually helpful; these include:

- Gonorrhea: Microscopic examination of smears from the lesions showing Gram-negative diplococci; culture and sensitivity tests of smears taken from lesions

- Lymphogranuloma venereum: Genotyping of Chlamydia trachomatis to detect DNA by PCR

- Genital or rectal herpes: Swabs from rectal vesicles or ulcers to detect DNA by PCR.

- Syphilis: Dark-field microscopy, PCR, direct fluorescent antibody test, treponemal antigen-based enzyme immunoassays (EIAs) for immunoglobulin (Ig)G and IgM antibodies, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay (TPHA), Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay (TPPA), and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test [20]

Treatment / Management

C. jejuni or Salmonella

Not all infectious colitis requires antibiotic therapy; patients with mild-to-moderate C. jejuni or Salmonella infections do not need antibiotic treatment because the infection is self-limited. Treatment with quinolinic acid antibiotics is only for patients with dysentery and high fever suggestive of bacteremia. Also, patients with AIDS, malignancy, transplantation, prosthetic implants, valvular heart disease, or extreme age require antibiotic therapy.

C. Diff

For mild-to-moderate C. diff infection, metronidazole is the preferred treatment. In severe cases of C. diff infection, oral vancomycin is recommended. In complicated cases, oral vancomycin with intravenous metronidazole is the recommendation.[18]

Enterohemorrhagic E. Coli

In patients, particularly children, with enterohemorrhagic E. coli (E. coli O157:7H and non-O157:H7), antibiotics are not recommendations for treating infection because killing the bacteria can lead to increased release of Shigella toxins and enhance the risk of the hemolytic uremic syndrome.[2]

Mycobacterium Tuberculosis

Because of rising multidrug resistance to antituberculous treatment, cases with active Mycobacterium tuberculosis colitis receive therapy with rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol for 9 to 12 months. The reader should review the recent guidelines by the World Health Organisation on treating developing resistance to tuberculosis.[19]

CMV

Most immunocompetent patients with CMV colitis may need no treatment with antiviral medications. However, antiviral therapy in immunocompetent patients with CMV colitis could be limited to males over the age of 55 who suffer from severe disease and have comorbidities affecting the immune system, such as diabetes mellitus or chronic renal failure; consider an assessment of the colon viral load. The drug of choice is oral or intravenous ganciclovir.[19]

E. Histolytica

Treatment of E. histolytica is recommended even in asymptomatic individuals. Noninvasive colitis may be treated with paromomycin to eliminate intraluminal cysts. Metronidazole is the antimicrobial of choice for invasive amoebiasis. Medications with longer half-lives (such as tinidazole and ornidazole) allow for shorter treatment periods and are better tolerated. After completing a 10-day course of a nitroimidazole, the patient should be placed on paromomycin to eradicate the luminal parasites. Fulminant amoebic colitis requires the addition of broad-spectrum antibiotics to the treatment due to the risk of bacterial translocation.[21]

Gonorrhea

Because of emerging resistance in gonorrhea, current treatment as per current guidelines comprises intramuscular ceftriaxone 500 mg together with an oral dose of azithromycin 1 g. Alternative protocols could be cefixime 400 mg stat or ciprofloxacin 500 mg orally stat.

Lymphogranuloma Venereum

The treatment of lymphogranuloma venereum uses doxycycline orally twice daily for 3 weeks or erythromycin 500 mg 4 times daily for 3 weeks.[22]

HSV

Genital or rectal HSV is treated with acyclovir 400 mg 3 times daily or valaciclovir 500 mg twice daily for 5 days. Analgesia and saline bathing could soothe the pain. Intravenous therapy is an option if the patient tolerates oral treatment poorly. Consider prolonging treatment if new lesions develop. For recurrent genital or rectal herpes, lesions are usually mild and may need no specific treatment. Symptomatic treatment could help. Challenging cases, such as those with recurrence at short intervals, may require referral for specialized advice. The partner should also have an examination and treatment if the lesion is active.

Syphilis

Syphilis treatment is with penicillin (the drug of choice). A single dose of 2.4 mega units of intramuscular benzathine benzylpenicillin is recommended for early syphilis, or 3 doses at weekly intervals with late syphilis. Doxycycline could be an alternative treatment for individuals sensitive to penicillin. Follow up with patients to ensure clearance from infection and notification are required.[23]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for infectious colitis include the following:

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Colorectal cancer

- Diverticulitis

- Ischemic colitis

- Irritable bowel disease

- Drug-induced colitis

- Radiation-associated colitis

- Colitis complicating immune deficiency disorders

- Graft-versus-host disease

- Acute appendicitis or ileocecal mass; the differential diagnosis may include:

- Yersinia enterocolitica infection

- Crohn disease

- Amoebic colitis

- Ulcerative colitis

- Colorectal cancer involving the cecum

Prognosis

Most infectious colitis cases last approximately 7 days, with severe cases lingering for several weeks. If left untreated, prolonged disease may be confused for ulcerative colitis.[24]

Complications

The complications that can manifest with infectious colitis are as follows:

- Intestinal perforation

- Toxic megacolon (C. diff–associated colitis, Salmonella, Shigella, C. jejuni, Cytomegalovirus, Rotavirus), and fulminant form of amebiasis

- Pseudomembrane formation (C. diff)

- Hemorrhagic colitis (enteroinvasive E. coli, enterohemorrhagic E. coli)

- Hemolytic-uremic syndrome (enterohemorrhagic E. coli, C. jejuni, Shigella)

- Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome, dyspepsia

- Guillain-Barre syndrome (C. jejuni colitis [serotype HS:19], Cytomegalovirus colitis)

- Encephalitis, seizure (Shigella)

- Reactive arthritis (Shigella, C. jejuni, Yersinia enterocolitica colitis)

- Pancreatitis, cholecystitis, meningitis, purulent arthritis (C. jejuni)

- Septic shock and death (Shigella, C. diff)

- Elevated serum pancreatic enzymes without clinical pancreatitis (Salmonella)

- Renal failure, shock (C. diff)

- Hypoglycemia, hyponatremia (Shigella)

- Erythema nodosum (Yersinia enterocolitica)

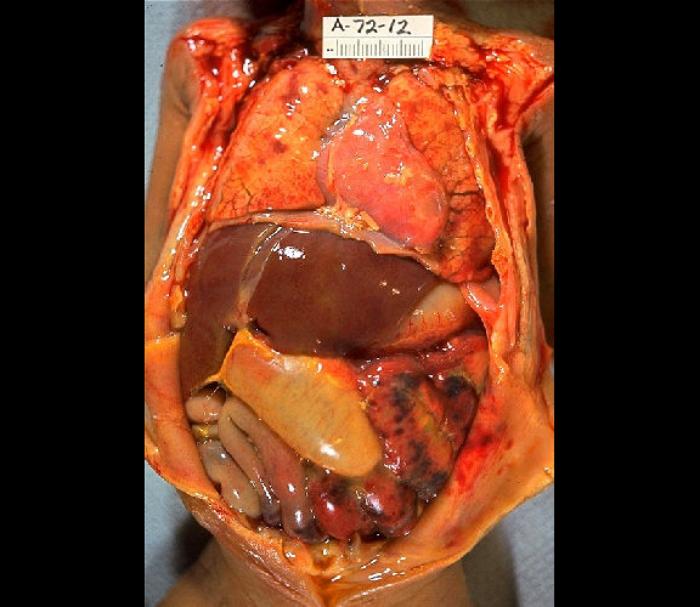

Patients with CMV colitis complicating inflammatory bowel disease may develop severe hemorrhage, megacolon, fulminant colitis, or colon perforation. These complications contribute to the high risk of mortality (see Image. Gross Pathology of Neonatal Necrotizing Enterocolitis).[23][25][26][27][23]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients need to receive counseling regarding the importance of antibiotic adherence and any signs of relapse or worsening condition.

Pearls and Other Issues

In managing patients presenting with colitis, computed tomography scans, colonoscopy, and biopsies could help differentiate between infectious and noninfectious colitis. However, these investigations are of little help in deciding the infectious agent causing colitis. Microbiological studies, including microscopy, cultures, sensitivity, and PCR DNA tests, are highly valuable in defining an infectious cause's etiology. Treatment of infectious colitis should be individualized depending on the patient’s age, causative agent, risk factors, presence of comorbidities, and current guidelines for managing infectious colitis. Antibiotic treatment of children with E. coli O157:H7 infection increases the risk of hemolytic uremic syndrome and should be avoided.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Infectious colitis is complex and requires an interprofessional team for the diagnosis, management, and early detection of complications. The team is comprised of a gastroenterologist, infectious disease consultant, pathologist, microbiologist, pharmacist, clinical pharmacologist, and general practitioner, which covers the range of expertise needed for managing infectious colitis and handling any complications. All members of the interprofessional healthcare team, including clinicians (MDs, DOs, NPs, PAs), specialists, specialty-trained nursing staff, and pharmacists, need to communicate and collaborate across disciplinary lines in their areas of expertise to keep the entire team informed and current on the status of the case and changes required. If signs and symptoms fail to resolve, or if signs or symptoms of dehydration develop, clinicians should schedule a follow-up appointement or possibly recommend emergency department evaluation. Careful assessment of the patient condition and involvement of the healthcare team in evaluation and decision-making is necessary for better outcomes. Patient education should focus on teaching patients to wash hands, eating only well-cooked foods, and drinking bottled water, particularly during traveling, which are the essential preventable measures that patients need to know.