[1]

Friedlander E, Pascual PM, Da Costa Belisario J, Serafini DP. Subluxation of the Cricoarytenoid Joint After External Laryngeal Trauma: A Rare Case and Review of the Literature. Indian journal of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery : official publication of the Association of Otolaryngologists of India. 2017 Mar:69(1):130-132. doi: 10.1007/s12070-016-1028-7. Epub 2016 Oct 18

[PubMed PMID: 28239594]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[2]

Oppenheimer AG, Gulati V, Kirsch J, Alemar GO. Case 223: Arytenoid Dislocation. Radiology. 2015 Nov:277(2):607-11. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015140145. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26492026]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[3]

Tolley NS, Cheesman TD, Morgan D, Brookes GB. Dislocated arytenoid: an intubation-induced injury. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 1990 Nov:72(6):353-6

[PubMed PMID: 2241051]

[4]

Rubin AD, Hawkshaw MJ, Moyer CA, Dean CM, Sataloff RT. Arytenoid cartilage dislocation: a 20-year experience. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2005 Dec:19(4):687-701

[PubMed PMID: 16301111]

[5]

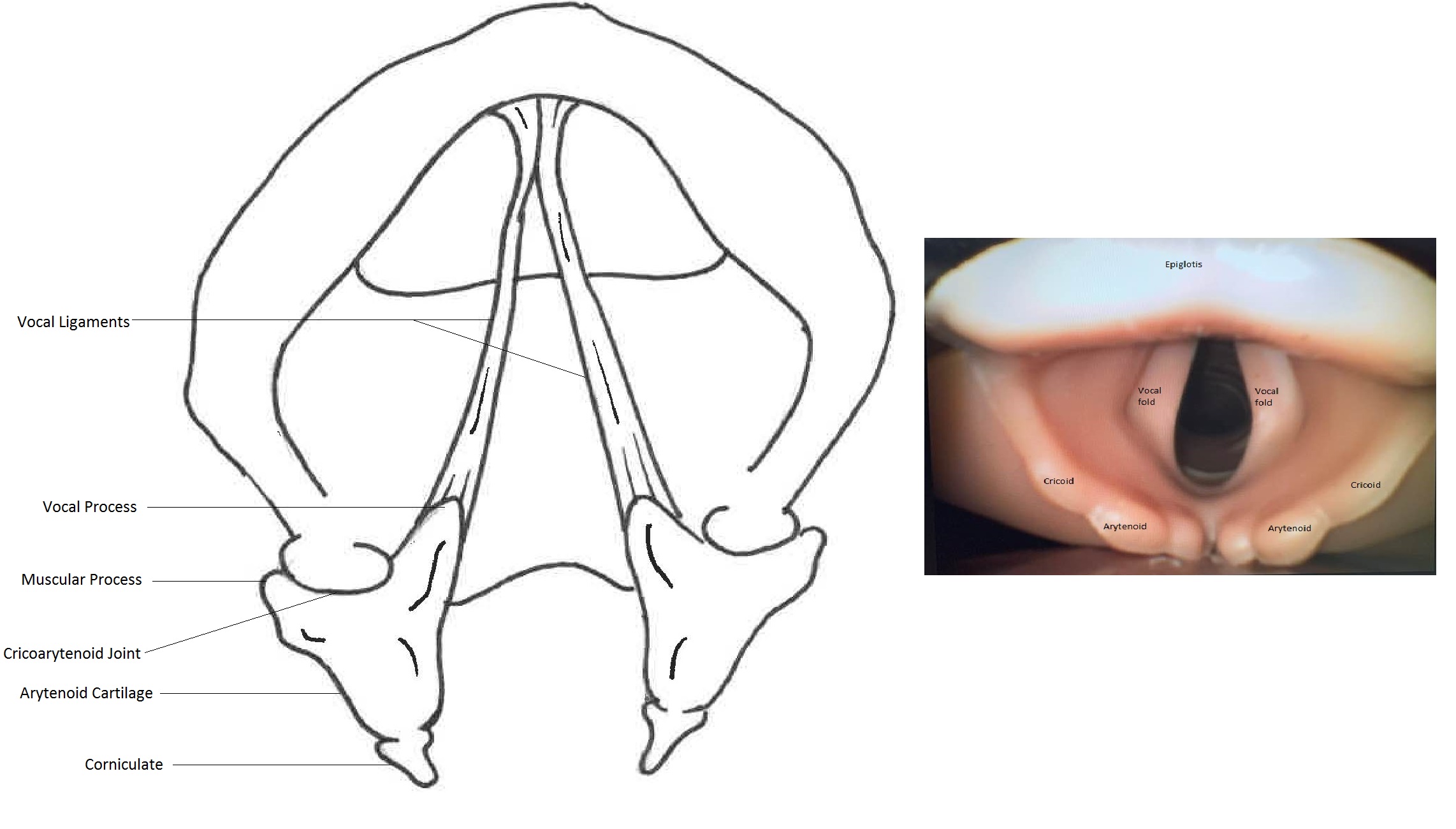

Andaloro C, Sharma P, La Mantia I. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Larynx Arytenoid Cartilage. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:():

[PubMed PMID: 30020624]

[6]

Allen E, Minutello K, Murcek BW. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Larynx Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:():

[PubMed PMID: 29261997]

[7]

Wu L, Shen L, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Huang Y. Association between the use of a stylet in endotracheal intubation and postoperative arytenoid dislocation: a case-control study. BMC anesthesiology. 2018 May 31:18(1):59. doi: 10.1186/s12871-018-0521-9. Epub 2018 May 31

[PubMed PMID: 29855263]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[8]

Lee DH, Yoon TM, Lee JK, Lim SC. Clinical Characteristics of Arytenoid Dislocation After Endotracheal Intubation. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2015 Jun:26(4):1358-60. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000001749. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26080195]

[9]

Debo RF, Colonna D, Dewerd G, Gonzalez C. Cricoarytenoid subluxation: complication of blind intubation with a lighted stylet. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 1989 Jul:68(7):517-20

[PubMed PMID: 2791919]

[10]

Mikuni I, Suzuki A, Takahata O, Fujita S, Otomo S, Iwasaki H. Arytenoid cartilage dislocation caused by a double-lumen endobronchial tube. British journal of anaesthesia. 2006 Jan:96(1):136-8

[PubMed PMID: 16311281]

[11]

Cho R, Zamora F, Dincer HE. Anteromedial Arytenoid Subluxation Due to Severe Cough. Journal of bronchology & interventional pulmonology. 2018 Jan:25(1):57-59. doi: 10.1097/LBR.0000000000000403. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 28926355]

[12]

Unusual cause of hoarseness: Arytenoid cartilage dislocation without a traumatic event., Okazaki Y,Ichiba T,Higashi Y,, The American journal of emergency medicine, 2018 Jan

[PubMed PMID: 29066184]

[13]

Nerurkar N, Chhapola S. Arytenoid subluxation after a bout of coughing: a rare case. American journal of otolaryngology. 2012 Mar-Apr:33(2):275-8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2011.07.001. Epub 2011 Aug 15

[PubMed PMID: 21840624]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[14]

Rieger A, Hass I, Gross M, Gramm HJ, Eyrich K. [Intubation trauma of the larynx--a literature review with special reference to arytenoid cartilage dislocation]. Anasthesiologie, Intensivmedizin, Notfallmedizin, Schmerztherapie : AINS. 1996 Jun:31(5):281-7

[PubMed PMID: 8767240]

[15]

Lou Z, Yu X, Li Y, Duan H, Zhang P, Lin Z. BMI May Be the Risk Factor for Arytenoid Dislocation Caused by Endotracheal Intubation: A Retrospective Case-Control Study. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2018 Mar:32(2):221-225. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2017.05.010. Epub 2017 Jun 7

[PubMed PMID: 28601417]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[16]

Tsuru S, Wakimoto M, Iritakenishi T, Ogawa M, Hayashi Y. Cardiovascular operation: A significant risk factor of arytenoid cartilage dislocation/subluxation after anesthesia. Annals of cardiac anaesthesia. 2017 Jul-Sep:20(3):309-312. doi: 10.4103/aca.ACA_71_17. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 28701595]

[17]

Norris BK, Schweinfurth JM. Arytenoid dislocation: An analysis of the contemporary literature. The Laryngoscope. 2011 Jan:121(1):142-6. doi: 10.1002/lary.21276. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 21181984]

[18]

Kambic V, Radsel Z. Intubation lesions of the larynx. British journal of anaesthesia. 1978 Jun:50(6):587-90

[PubMed PMID: 666934]

[19]

Rudert H. [Uncommon injuries of the larynx following intubation. Recurrent paralysis, torsion and luxation of the cricoarytenoid joints]. HNO. 1984 Sep:32(9):393-8

[PubMed PMID: 6501014]

[21]

Mallon AS, Portnoy JE, Landrum T, Sataloff RT. Pediatric arytenoid dislocation: diagnosis and treatment. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2014 Jan:28(1):115-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2013.08.016. Epub 2013 Oct 8

[PubMed PMID: 24119642]

[22]

Chen X, Wang Z, Xia Z. [Cause and treatment analysis of arytenoid dislocation caused by endotracheal intubation after general anesthesia of children]. Lin chuang er bi yan hou tou jing wai ke za zhi = Journal of clinical otorhinolaryngology, head, and neck surgery. 2014 Nov:28(21):1701-2

[PubMed PMID: 25735107]

[23]

Tan V, Seevanayagam S. Arytenoid subluxation after a difficult intubation treated successfully with voice therapy. Anaesthesia and intensive care. 2009 Sep:37(5):843-6

[PubMed PMID: 19775054]

[24]

Talmi YP, Wolf M, Bar-Ziv J, Nusem-Horowitz S, Kronenberg J. Postintubation arytenoid subluxation. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 1996 May:105(5):384-90

[PubMed PMID: 8651633]

[25]

Habe K,Kawasaki T,Horishita T,Sata T, [Airway problem during the operation with beach-chair position: a case of arytenoid dislocation and the relationship between intra-cuff pressure of endotrachial tube and the neck position]. Masui. The Japanese journal of anesthesiology. 2011 Jun

[PubMed PMID: 21710762]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[26]

Ichikawa J, Kodaka M, Nishiyama K, Kawamata M, Komori M, Ozaki M. [Prolonged hoarseness and arytenoid dislocation after endotracheal intubation]. Masui. The Japanese journal of anesthesiology. 2010 Dec:59(12):1490-3

[PubMed PMID: 21229688]

[27]

Díaz-Tantaleán JA, Velasco M, Muñoz X. Cricoarytenoid subluxation: another cause of pseudoasthma. Chest. 2014 Nov:146(5):e182-e183. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1603. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25367498]

[28]

Zhuang P, Nemcek S, Surender K, Hoffman MR, Zhang F, Chapin WJ, Jiang JJ. Differentiating arytenoid dislocation and recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis by arytenoid movement in laryngoscopic video. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2013 Sep:149(3):451-6. doi: 10.1177/0194599813491222. Epub 2013 May 29

[PubMed PMID: 23719396]

[29]

Kösling S,Heider C,Heider C,Bartel-Friedrich S, [CT findings in isolated laryngeal trauma]. Laryngo- rhino- otologie. 2005 Aug

[PubMed PMID: 16080060]

[30]

Wang Z, Xia L, Wang C. [Utility of spiral computed tomography in the study of dislocation of cricoarytenoid joint]. Zhonghua er bi yan hou ke za zhi. 2002 Jun:37(3):223-5

[PubMed PMID: 12772329]

[31]

Alexander AE Jr, Lyons GD, Fazekas-May MA, Rigby PL, Nuss DW, David L, Williams K. Utility of helical computed tomography in the study of arytenoid dislocation and arytenoid subluxation. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 1997 Dec:106(12):1020-3

[PubMed PMID: 9415597]

[32]

Schroeder U, Motzko M, Wittekindt C, Eckel HE. Hoarseness after laryngeal blunt trauma: a differential diagnosis between an injury to the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve and an arytenoid subluxation. A case report and literature review. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2003 Jul:260(6):304-7

[PubMed PMID: 12883952]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[33]

Close LG, Merkel M, Watson B, Schaefer SD. Cricoarytenoid subluxation, computed tomography, and electromyography findings. Head & neck surgery. 1987 Jul-Aug:9(6):341-8

[PubMed PMID: 3623957]

[34]

Cao L, Wu X, Mao W, Hayes C, Wei C. Closed reduction for arytenoid dislocation under local anesthesia. Acta oto-laryngologica. 2016 Aug:136(8):812-8. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2016.1157267. Epub 2016 Mar 22

[PubMed PMID: 27002978]

[35]

Lee SW, Park KN, Welham NV. Clinical features and surgical outcomes following closed reduction of arytenoid dislocation. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2014 Nov:140(11):1045-50. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.2060. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25257336]

[36]

Ryu IS, Nam SY, Han MW, Choi SH, Kim SY, Roh JL. Long-term voice outcomes after thyroplasty for unilateral vocal fold paralysis. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2012 Apr:138(4):347-51. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2012.42. Epub 2012 Mar 19

[PubMed PMID: 22431862]

[37]

Cura O, Uluoz U, Kirazli T, Karci B. [Arytenoidopexy in bilateral abductor paralysis of the glottis]. Revue de laryngologie - otologie - rhinologie. 1991:112(1):59-62

[PubMed PMID: 2052789]

[38]

Zimmermann TM, Orbelo DM, Pittelko RL, Youssef SJ, Lohse CM, Ekbom DC. Voice outcomes following medialization laryngoplasty with and without arytenoid adduction. The Laryngoscope. 2019 Aug:129(8):1876-1881. doi: 10.1002/lary.27684. Epub 2018 Dec 24

[PubMed PMID: 30582612]

[39]

Rontal E, Rontal M. Botulinum toxin as an adjunct for the treatment of acute anteromedial arytenoid dislocation. The Laryngoscope. 1999 Jan:109(1):164-6

[PubMed PMID: 9917060]

[40]

Tigges M, Hess M. [Glottis injection to improve voice function : Review of more than 500 operations]. HNO. 2015 Jul:63(7):489-96. doi: 10.1007/s00106-015-0029-2. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26104911]

[41]

Mallur PS, Rosen CA. Vocal fold injection: review of indications, techniques, and materials for augmentation. Clinical and experimental otorhinolaryngology. 2010 Dec:3(4):177-82. doi: 10.3342/ceo.2010.3.4.177. Epub 2010 Dec 22

[PubMed PMID: 21217957]

[42]

Sulica L, Rosen CA, Postma GN, Simpson B, Amin M, Courey M, Merati A. Current practice in injection augmentation of the vocal folds: indications, treatment principles, techniques, and complications. The Laryngoscope. 2010 Feb:120(2):319-25. doi: 10.1002/lary.20737. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 19998419]

[43]

Reiter R, Hoffmann TK, Rotter N, Pickhard A, Scheithauer MO, Brosch S. [Etiology, diagnosis, differential diagnosis and therapy of vocal fold paralysis]. Laryngo- rhino- otologie. 2014 Mar:93(3):161-73. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1355373. Epub 2013 Oct 17

[PubMed PMID: 24135826]

[44]

Kato T, Wada K, Morioka N, Onuki E, Ozaki M, Ishida T. [Arytenoid cartilage dislocation caused by endotracheal intubation which resolved spontaneously]. Masui. The Japanese journal of anesthesiology. 2010 Jun:59(6):724-6

[PubMed PMID: 20560374]

[45]

Abe K, Nishino H, Makino N, Ishikawa K, Ishikawa K, Imai K, Ichimura K. [Fiberscopic reduction under local anesthesia for anterior arytenoid cartilage dislocation]. Nihon Jibiinkoka Gakkai kaiho. 2007 Jan:110(1):13-9

[PubMed PMID: 17302296]