Introduction

The nail functions by protecting the digits and contributing to tactile sensation. Understanding nail anatomy is not only essential for understanding physiology but also comprehending the pathophysiology behind many nail presentations. Clinically, many cutaneous and systemic diseases can manifest on the nails. While a thorough history and physical can often correlate nail findings with their etiology, a biopsy may be necessary to reach a final diagnosis. Understanding the anatomy is important when obtaining tissue samples since an injury to the vital blood vessels and nerves supplying the nail can cause complications. This article aims to review all significant aspects of nail anatomy and address the clinical considerations above.

Structure and Function

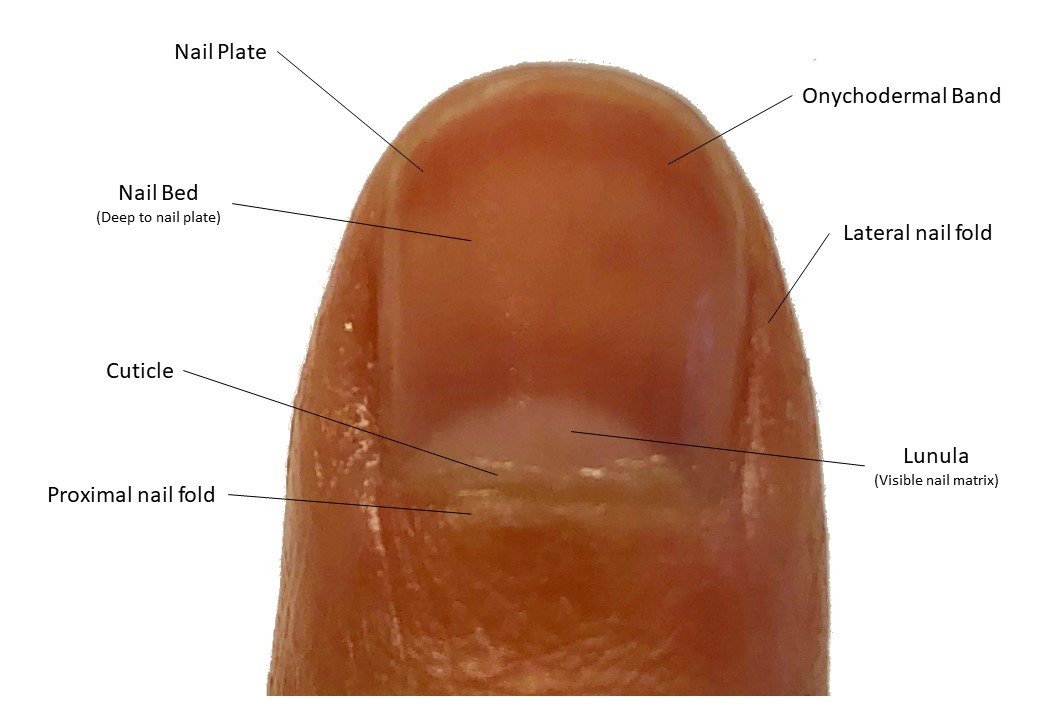

The nail has many soft tissue structures that help support and form the hard-outer nail, known as the nail plate. The attached figure depicts the gross structures described below.

Nail Folds

The nail folds are soft tissue structures that protect the lateral and proximal edges of the nail plate. The proximal nail fold protects most of the nail matrix from trauma and ultraviolet rays.[1]

Mantle

The mantle is the skin covering the matrix and base of the nail plate.

Cuticle

The cuticle (also known as the eponychium) grows from the proximal nail bed and adheres to the nail plate. Together, the proximal nail fold and cuticle form a protective seal against any irritants that may disrupt the matrix underneath.[1]

Nail Matrix

The nail matrix is located deep to the proximal nail fold and nail plate. The proximal nail matrix begins about halfway between the distal interphalangeal joint and the proximal nail fold. The distal nail matrix is visible through the nail plate as a white half-moon structure called the lunula. The nail matrix is responsible for the formation of the hard nail plate and is the only part of the nail unit that contains melanocytes. The nail cells, termed onychocytes, are pushed superficially and distally to form the nail plate. Different parts of the nail matrix form different sections of the nail plate. Generally, the dorsal aspect of the nail plate is formed from the proximal nail matrix, and the ventral nail plate is formed from the distal nail matrix. However, 80% of the nail plate is made from the proximal nail matrix. Therefore, a biopsy or surgery of the distal nail matrix will produce minimal damage to the nail plate.[1]

Nail Plate

The nail plate is the hard, keratinized structure made from compact onychocytes, organized in a lamellar pattern. The dorsal surface of the nail plate is smooth with longitudinal ridges. Below the nail plate are the nail bed and part of the nail matrix. The nail bed and nail folds act as strong attachment points that help the free edge of the nail function as a tool without loosening the nail plate or causing pain.[1]

Nail Bed

The nail bed is attached to the ventral surface of the nail plate and begins distal to the lunula and terminates at the hyponychium. The nail plate is attached to the nail bed through longitudinal epidermal ridges. These ridges on the ventral nail plate surface are complementary to the ridges on the nail bed, which function to increase the surface area of the nail plate’s attachment to the underlying nail bed, thus augmenting the adhesion between these two surfaces. The nail bed does not produce a stratum corneum since the keratins necessary for the formation of this layer of the epidermis are not present. However, if onycholysis or loss of the nail plate occurs, the nail bed loses the longitudinal ridges and begins to express the keratins necessary to produce the stratum corneum. Below the nail bed is a thin layer of the collagenous dermis which adheres to the periosteum of the underlying distal phalanx. The lack of subcutaneous fat can increase the risk of osteomyelitis of the distal phalanx in the setting of a nail infection.[1]

Hyponychium

The hyponychium is the area distal to the nail bed and beneath the free edge of the nail plate.[1]

Onychodermal Band

The onychodermal band is part of the distal nail bed that is grossly represented in a contrasting color. It functions as the first barrier of protection on the free edge of the nail and is analogous to the cuticle. Changes in the color can correspond to different diseases or variations in vascular supply.[1]

Embryology

The nail starts to become visible around 8 weeks of gestation as a ridge on the digits. At 14 weeks, proximal fold has formed, and by 16 weeks, the basic nail unit can be recognized. At 5 months gestation, a well-formed nail plate completely covers the nail bed.[1]

Studies show the nail and underlying distal phalanx have an embryologic relationship, which changes after birth and throughout life. Signaling molecules, such as bone morphogenic proteins, play a role in the formation of both nail and bone structures in the fingers. Congenital nail dystrophies have been associated with underlying bone defects, such as a bifid phalanx.[1] Adults with psoriatic arthritis are more likely to have nail manifestations of their disease.[2] Inflammation of the underlying joint and bone can disturb the proximal nail matrix, resulting in nail pitting or crumbling.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The nail unit has a rich blood supply with many anastomotic channels, to ensure proper blood flow, even if an occlusion occurs when the fingers are gripping an object.

Both the radial and ulnar artery branch into superficial and deep palmar arches in the hand. The superficial palmar arch supplies most of the blood to the fingers, by branching into the common digital arteries.[3] Each common digital artery gives rise to 2 proper digital arteries, which travel laterally on either side of each finger.[3] This vessel then branches proximal to the distal interphalangeal joint into the dorsal digital arteries.[3] The dorsal digital branch travels over the distal interphalangeal joint and becomes the superficial arcade.[3] This tortuous vessel travels transversely about half a centimeter proximal to the cuticle and supplies the nail fold and nail matrix.[1] The superficial arcade gives off multiple longitudinal subungual vessels that travel in parallel distally, and anastomose with palmar digital arteries to form the proximal and distal subungual arcades, which supply the rest of the nail unit and nail bed. While there is a wide anatomic variation in these smaller vessels of the nail unit, all the vessels in the distal digits exhibit a notable tortuosity, which is thought to be a protective mechanism in case of occlusion.[3]

Venous drainage parallels arterial supply, except the vessels, are superficial and the collecting veins are located in the lateral nail folds.[3]

A unique vascular structure a part of the nail unit are cavernous blood vessels known as glomus bodies. These end-organ apparatuses are arteriovenous anastomoses that bypass a capillary bed. These structures are surrounded by cuboidal epithelial cells and pericytes, that contract asynchronously with arterioles.[1] In cold temperatures, arterioles feeding the glomus bodies will contract while the glomus bodies dilate. They are important for temperature regulation and preservation of blood flow in cold conditions.[1]

Nerves

The distal digits have a rich neural innervation since the fingers are responsible for fine tactile discrimination. The nerves innervating the nail unit mimic the arterial supply. There are paired digital nerves innervating the palmar and dorsal surfaces of each digit.[1] The dorsal digital nerve branches and runs over the distal interphalangeal joint to innervate the proximal nail fold.[3] The palmar digital nerve travels with the proper digital artery past the distal interphalangeal joint. It then trifurcates into branches that supply the rest of the nail unit and the pulp of the distal finger.[3]

Surgical Considerations

Nail surgery needs careful consideration of the anatomy of the nail unit and its surroundings. Understanding the neural innervation and blood supply of the tissue can help the surgery proceed without complications.

Before the surgery, once the nail has been thoroughly disinfected, an anesthetic should be used to ensure the patient does not feel pain. Any local anesthetic can be used, such as lidocaine, mepivacaine, or prilocaine. However, one author suggests ropivacaine is a preferred anesthetic, due to its long duration of action, which can be helpful for patients since severe pain can follow nail surgery once the local anesthetic has worn off.[4] There are many techniques for digital anesthesia. The proximal digital block is a common technique with great anesthetic results. It is useful for any nail surgery, however, if too much volume is injected, compression of the vessels may cause ischemia.[3][4] Local injection around the nail unit can avoid this ischemic complication while still offering the advantage of proper anesthesia. Another option is transthecal anesthesia. This technique is useful for the second, third, or fourth digits. The local anesthetic is injected through the metacarpophalangeal volar joint crease into the flexor digitorum tendon sheath. This technique also avoids ischemic complications and damage to the neurovascular bundles in the fingers.[4]

To accurately diagnose nail disease, a nail biopsy may be necessary for pathologic confirmation.

- Punch biopsies are useful for nail bed and matrix diseases. A punch biopsy of the nail matrix should be no larger than 3 mm.[4]

- Fusiform biopsies are oriented transversely in the matrix and longitudinally on the nail bed. Due to the delicacy of the matrix, it should not be squeezed during biopsies or cut during suturing.[4]

- Lateral longitudinal biopsies are taken from the distal interphalangeal joint to the hyponychium, just medial to the lateral nail fold. This technique leaves the lateral nail fold intact and ensures no matrix remnant is left behind. Since the nail grows over months, this biopsy technique allows the assessment of the progression of the nail disease.[4]

- Biopsies of pigmented nail streaks are of utmost importance to rule out the possibility of subungual melanoma. A specialized technique has been developed to acquire an adequate superficial nail matrix biopsy to diagnose melanoma while preventing post-surgical nail dystrophy. The proximal nail fold is incised and retracted to expose the proximal soft nail. The soft nail is then cut and elevated to expose the pigmented matrix underneath. A very thin piece of pigmented matrix tissue is removed and sent to the lab for further evaluation. The nail plate and proximal nail fold are replaced and closed with either a suture or suture strips.[4]

Clinical Significance

The nails can be important clues to local and even systemic disease. Listed below are descriptions of several nail findings and diseases.

Nail Abnormalities Associated with Localized Conditions

Leukonychia (Leuk: white; onychia: nail): White discoloration on the nail due to faulty keratinization of the distal nail matrix, since the distal matrix produces the ventral nail plate. Transverse leukonychia, also known as Mee’s lines, are transverse parallel white bands in the nail. Repeated systemic stressors may cause this finding.[5]

Longitudinal melanonychia (melano: dark pigment; onychia: nail): Band of dark pigment in the nail due to the presence of melanin in the nail plate. Benign pigment changes can be difficult to distinguish from ungual melanoma. Therefore, a biopsy may be necessary for final diagnosis.

Onycholysis (onycho: nail; lysis: loosening): Occurs when the distal nail plate is no longer securely attached to the nail bed and other supporting structures such as the nail folds. Onycholysis can be caused by trauma or may be associated with many cutaneous conditions like psoriasis and onychomycosis.[6]

Onychomadesis (onycho: nail; ma(l): badly; desis: bound): Shedding and separation of the proximal nail plate from the proximal nail fold. It may be due to complete cessation of both the proximal and distal nail matrix caused by systemic stressors or trauma.

Onychomycosis (onycho: nail; mycosis: fungus): Presents as a thickened yellow discolored nail plate caused by a fungal infection of the nail and its surrounding tissue. While it most commonly affects the toes, it can also affect the nails of the fingers.

Onychorrhexis (onych: nail; orrhexis: rupture): Longitudinal splits occurring in the distal free edge of the nail.[7]

Onychoschizia: Distal transverse lamellar splitting of the free edge of the nail due to breakage in the intercellular adhesions in the nail plate.[8]

Paronychia: Presents as inflammation of the nail unit with possible surrounding crust and pustules due to infection of the nail folds. Trauma and manipulation of the nail folds and cuticle can cause loss of their protective effect leading to a risk of bacterial colonization.[1] The most common cause of acute paronychia is Staphylococcal aureus.

Squamous cell carcinoma: Presents as an erythematous mass that can disrupt nail morphology. Commonly mistaken for a benign lesion such as verrucous lessons, onychomyocis, or amelanotic melanoma. Treatment involves Mohs surgery and possible amputation. [9]

Subungual hematoma: Painful, red to black discolorations cause by bleeding of an underlying vascular bed. Caused by trauma. If associated with severe pain, nail puncture can be performed to release pressure.

Nail Abnormalities Associated with Systemic Conditions

Clubbing: Convex appearance of the nail that is caused by the thickening of the nail bed soft tissue. Commonly associated with vascular pathologies including cirrhosis, COPD, and celiac sprue. [10]

Koilonychia (koil: concave; onychia: nail): Thinned spoon-shaped nails due to abnormal nail matrix function. Although this can occur in normal individuals, it is a sign of severe iron deficiency anemia. Additionally, can be associated with hemochromatosis, trauma, Raynaud disease, hypothyroidism, and systemic lupus.

Pitting: Punctate depressions on the nail surface due to abnormal keratinization of the nail plate. Problems in the proximal nail matrix manifest as nail pitting since the proximal matrix is responsible for the formation of the dorsal nail plate. Nail pitting can be seen in psoriasis and alopecia areata.

Splinter hemorrhages: Small red to black thin longitudinal markings under the nail plate, which represent small areas of hemorrhage in the nail bed. Since the capillaries of the nail bed are aligned in a longitudinal fashion, clots in these subungual vessels manifest in this linear configuration.[1] They are most commonly caused by trauma or nail psoriasis and can rarely be associated with systemic illnesses like endocarditis.[11][12]

Subungual hyperkeratosis: Increased keratinized debris under the free edge of the distal nail, due to irregular keratinization of the distal nail bed and hyponychium. Causes of this phenomenon include trauma, psoriasis, and onychomycosis.[13]

Transverse nail grooves (Beau’s lines): Transverse indentation in the nails that correspond to a temporary halt in nail matrix proliferation. It can be seen in local trauma, infection, or the setting of significant physiologic stressors. Systemic illnesses include severe illness, Raynaud disease, pemphigus, chemotherapy, and high fever. [1]

Trachyonychia (trachy: rough; onychia: nails): Presents as longitudinal rough, thick ridges and nail brittleness resulting from defective keratinization of the proximal nail matrix. Dermatologic diseases such as psoriasis, lichen planus, atopic dermatitis, and alopecia areata can present with these nail findings.[14]