[1]

Kitagawa J, Nakagawa K, Hasegawa M, Iwakami T, Shingai T, Yamada Y, Iwata K. Facilitation of reflex swallowing from the pharynx and larynx. Journal of oral science. 2009 Jun:51(2):167-71

[PubMed PMID: 19550082]

[2]

Thexton AJ. Mastication and swallowing: an overview. British dental journal. 1992 Oct 10:173(6):197-206

[PubMed PMID: 1389633]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[3]

Sakamoto Y. Classification of pharyngeal muscles based on innervations from glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves in human. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2009 Dec:31(10):755-61. doi: 10.1007/s00276-009-0516-9. Epub 2009 May 29

[PubMed PMID: 19479181]

[4]

Seki S, Sumida K, Yamashita K, Baba O, Kitamura S. Gross anatomical classification of the courses of the human lingual artery. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2017 Feb:39(2):195-203. doi: 10.1007/s00276-016-1696-8. Epub 2016 May 17

[PubMed PMID: 27189234]

[5]

Wang C, Kundaria S, Fernandez-Miranda J, Duvvuri U. A description of arterial variants in the transoral approach to the parapharyngeal space. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2014 Oct:27(7):1016-22. doi: 10.1002/ca.22273. Epub 2014 Feb 7

[PubMed PMID: 24510490]

[6]

Hellings P, Jorissen M, Ceuppens JL. The Waldeyer's ring. Acta oto-rhino-laryngologica Belgica. 2000:54(3):237-41

[PubMed PMID: 11082757]

[7]

Sakamoto Y. Morphological Features of the Glossopharyngeal Nerve in the Peripharyngeal Space, the Oropharynx, and the Tongue. Anatomical record (Hoboken, N.J. : 2007). 2019 Apr:302(4):630-638. doi: 10.1002/ar.23924. Epub 2018 Nov 1

[PubMed PMID: 30383337]

[8]

Gervasio A, D'Orta G, Mujahed I, Biasio A. Sonographic anatomy of the neck: The suprahyoid region. Journal of ultrasound. 2011 Sep:14(3):130-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jus.2011.06.001. Epub 2011 Jun 29

[PubMed PMID: 23396801]

[9]

Choi DY, Bae JH, Youn KH, Kim HJ, Hu KS. Anatomical considerations of the longitudinal pharyngeal muscles in relation to their function on the internal surface of pharynx. Dysphagia. 2014 Dec:29(6):722-30. doi: 10.1007/s00455-014-9568-z. Epub 2014 Aug 21

[PubMed PMID: 25142243]

[10]

Patoulias I, Rachmani E, Farmakis K, Rafailidis V, Kalogirou M, Patoulias D. A Bilateral, Non-syndromic, Type III Second Branchial Arch Sinus in a Neonate: a Case Report. Acta medica (Hradec Kralove). 2018:61(1):33-36. doi: 10.14712/18059694.2018.21. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30012248]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[11]

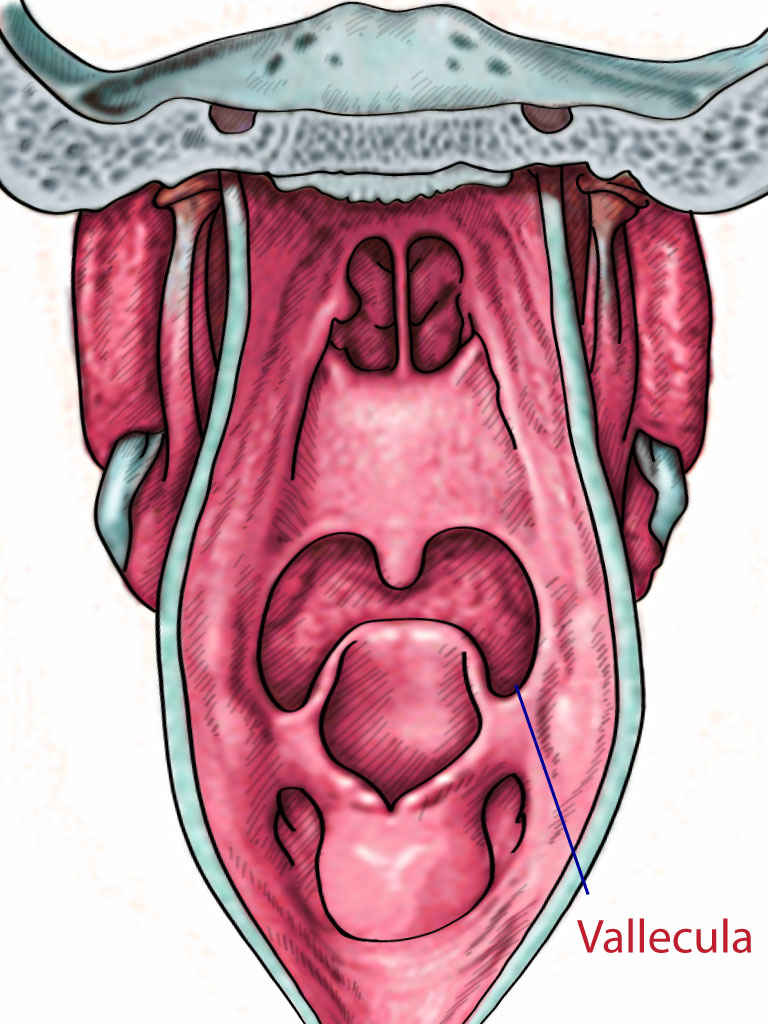

Laccourreye L, Garcia D, Ménard M, Brasnu D, Laccourreye O, Holsinger FC. Horizontal supraglottic partial laryngectomy for selected squamous carcinoma of the vallecula. Head & neck. 2008 Jun:30(6):756-64. doi: 10.1002/hed.20780. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 18286490]

[12]

Lee DH, Yoon TM, Lee JK, Lim SC. Clinical characteristics and surgical treatment outcomes of vallecular cysts in adults. Acta oto-laryngologica. 2015:135(11):1185-8. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2015.1062549. Epub 2015 Jul 3

[PubMed PMID: 26139619]

[13]

Zamfir-Chiru-Anton A, Gheorghe DC. Vallecular cysts in clinical practice: report of two cases. Journal of medicine and life. 2016 Jul-Sep:9(3):288-290

[PubMed PMID: 27974936]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[14]

Zalvan CH, Reilly E. Symptomatic vallecular cysts: diagnosis and management with the KTP laser. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2016 Aug:273(8):2111-6. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-4026-1. Epub 2016 Apr 7

[PubMed PMID: 27056198]

[15]

Nishikawa K, Yamada K, Sakamoto A. A new curved laryngoscope blade for routine and difficult tracheal intubation. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2008 Oct:107(4):1248-52. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318185cecb. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 18806035]

[16]

Seto A, Takenaka I, Aoyama K, Iwagaki T, Ishimura H, Takenaka Y, Kadoya T. [Efficacy of bougie in difficult intubation with the Airway Scope caused by inability to lift the epiglottis directly]. Masui. The Japanese journal of anesthesiology. 2010 Apr:59(4):525-30

[PubMed PMID: 20420153]