Continuing Education Activity

Aspergilloma and chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis (CCPA) are two forms of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis (CPA). These conditions, arising from the inhalation of Aspergillus spores, present overlapping clinical features and complexities in diagnosis and management. This course aims to equip clinicians with a comprehensive understanding of the epidemiology, history, diagnostic criteria, and evolving management approaches for aspergilloma and CCPA within the broader context of CPA. Participants will delve into the global prevalence of these conditions, emphasizing the higher incidence in regions with elevated rates of tuberculosis (TB). The discussion covers the predisposing factors, including bronchiectasis, emphysema, sarcoidosis, lung abscess, and lung cancer. Diagnosis and management criteria, which have evolved over the past decade, will be thoroughly explored, providing clinicians with up-to-date knowledge and tools to enhance patient care. This interprofessional learning experience emphasizes the collaborative roles of infectious disease clinicians, pulmonologists, radiologists, and surgeons in optimizing patient care for individuals with aspergilloma and CCPA. By participating in this course, learners will deepen their understanding of these complex conditions and improve their competence through an interdisciplinary approach, leading to enhanced patient outcomes.

Objectives:

Apply current guidelines for managing Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis (CPA), which encompasses simple aspergilloma and chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis.

Differentiate simple aspergilloma and chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis from other types of CPA.

Assess the radiologic signs associated with aspergilloma and chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis.

Collaborate with clinicians to manage symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with aspergilloma and chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis, seeking specialist consultation when needed.

Introduction

Inert saprophytic colonization of preexisting cavitary spaces in pulmonary parenchyma, its presentation, and complications are referred to as aspergilloma and CCPA. These conditions fall within the broader class of CPA, of which several distinct clinical entities are recognized, including aspergilloma, CCPA, chronic fibrotic pulmonary aspergillosis, aspergillus nodules, and subacute invasive aspergillosis.[1] It is important to emphasize that overlap in these CPA entities' clinical and radiographic features has led to confusion when interpreting the literature on their natural history and management aspects. Additional confusion is attributed to the differences in cumulative clinician experience when managing these entities. Published case series from regions with high TB prevalence may differ in diagnostic and management approaches compared to areas with lower prevalence, where aspergilloma is less common. Management approaches are controversial because small case series exist in the literature, but extensive, prospective, randomized studies are lacking.[2] Diagnosing and managing these chronic fungal infections are complex and challenging. The diagnosis is difficult as radiographic features may overlap with other lung diseases.[3] Moreover, since CPA develops most often in diseased lungs, it is difficult to determine how much of the radiological distortion reflects pathology due to the fungus versus the underlying lung disease.

The European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, The European Respiratory Society, and The Infectious Diseases Society of America have developed consensus definitions of CPA.[1][4][1]

Their diagnostic criteria are as follows:

Simple Aspergilloma

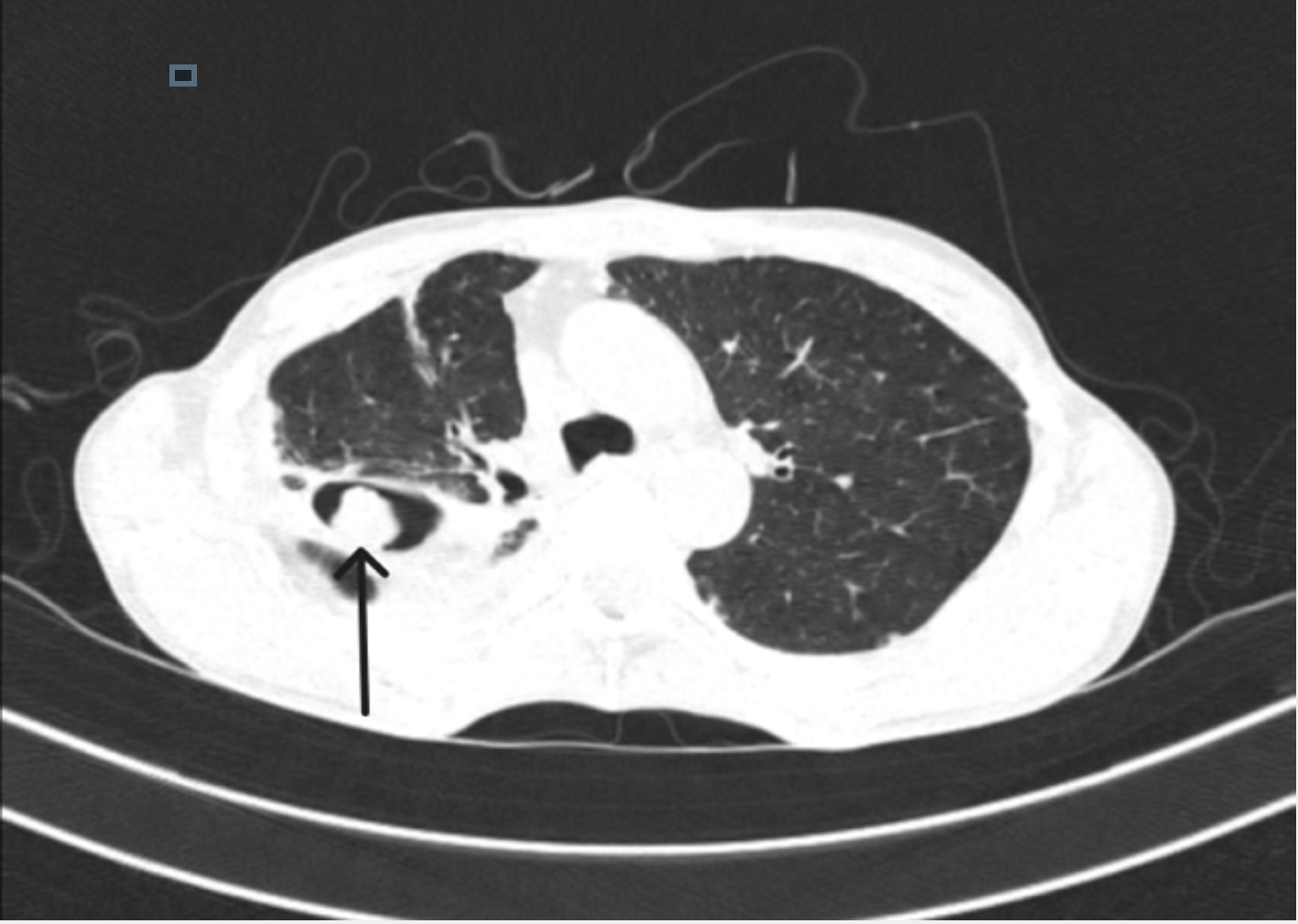

Single pulmonary cavity containing a fungal ball, with serological or microbiological evidence implicating Aspergillus spp in a non-immunocompromised patient with minor or no symptoms and no radiological progression over at least 3 months of observation (see Image. CT Lung Showing Aspergilloma Mass That Indicates Monod's Sign).

Chronic Cavitary Pulmonary Aspergillosis (CCPA)

One or more pulmonary cavities (with either a thin or thick wall) possibly containing 1 or more aspergillomas or irregular intraluminal material with serological or microbiological evidence implicating Aspergillus spp with significant pulmonary and/or systemic symptoms and overt radiological progression (new cavities, increasing pericavitary infiltrates or increasing fibrosis) over at least 3 months observation.

Chronic Fibrosing Pulmonary Aspergillosis (CFPA)

Severe fibrotic destruction of at least 2 lobes of the lung complicates CCPA, leading to a major loss of lung function. Severe fibrotic destruction of 1 lobe with a cavity is called CCPA, affecting that lobe. Usually, the fibrosis manifests as consolidation, but large cavities with surrounding fibrosis may be seen.

Aspergillus Nodule

An unusual form of CPA is one or more nodules that may or may not cavitate. They may mimic tuberculoma, carcinoma of the lung, coccidiomycosis, and other diagnoses and can only be definitively diagnosed on histology. Tissue invasion is not demonstrated, although necrosis is frequent.

Subacute Invasive Aspergillosis (SAIA)

Invasive aspergillosis, usually in mildly immunocompromised patients, occurs over 1 to 3 months and has variable radiological features, including cavitation, nodules, and progressive consolidation with abscess formation. Biopsy shows hyphae in invading lung tissue, and microbiological investigations reflect those in invasive aspergillosis, notably positive Aspergillus galactomannan antigens in blood or respiratory fluids.

The above definitions are not mutually discreet; progressive evolution between the disease categories may ensue.[5] While poorly understood, the factors contributing to disease progression likely include a combination of immune function, treatment response, and preexisting lung pathology. Pulmonary aspergilloma and CCPA are the focus of this article, and the terms aspergilloma, pulmonary mycetoma, and fungus ball are considered to describe the chronic colonization by aspergillus species within preexisting lung cavities or bronchiectatic parenchyma.

Etiology

Aspergillus species are ubiquitous saprophytes in the environment. Aspergillus is a filamentous fungus that thrives in a moist environment in soil, plants, and decaying vegetables. However, the conditions that favor the dispersion of spores are dry and dusty surroundings, hay barns, compost sites, etc. Aspergillus fumigatus is the most prevalent human pathogen, although A niger, A flavus, and A oxyzae are also reported to cause human disease.

Risk factors for Aspergillus-mediated lung disease, including aspergilloma and CCPA, are:

- Pulmonary tuberculosis (TB)

- Nontuberculous mycobacterial infection (NTM)

- Cystic fibrosis

- Chronic bronchiectasis

- Pneumoconiosis

- Post-infarct pulmonary cavity

- Post-radiation pulmonary cavity

- Sarcoidosis

- Bronchial cysts and bullae

- Chronic lung abscess

- Lung malignancy

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA)

Chronic Debilitating Condition (Impaired local bronchopulmonary defense)

- Malnutrition

- COPD

- Chronic liver disease

Immunosuppression

- Post-solid organ transplant

- Stem cell transplant

- Chemotherapy

- Neutropenia

- Prolonged corticosteroid use

- HIV

- Primary immunodeficiency syndromes

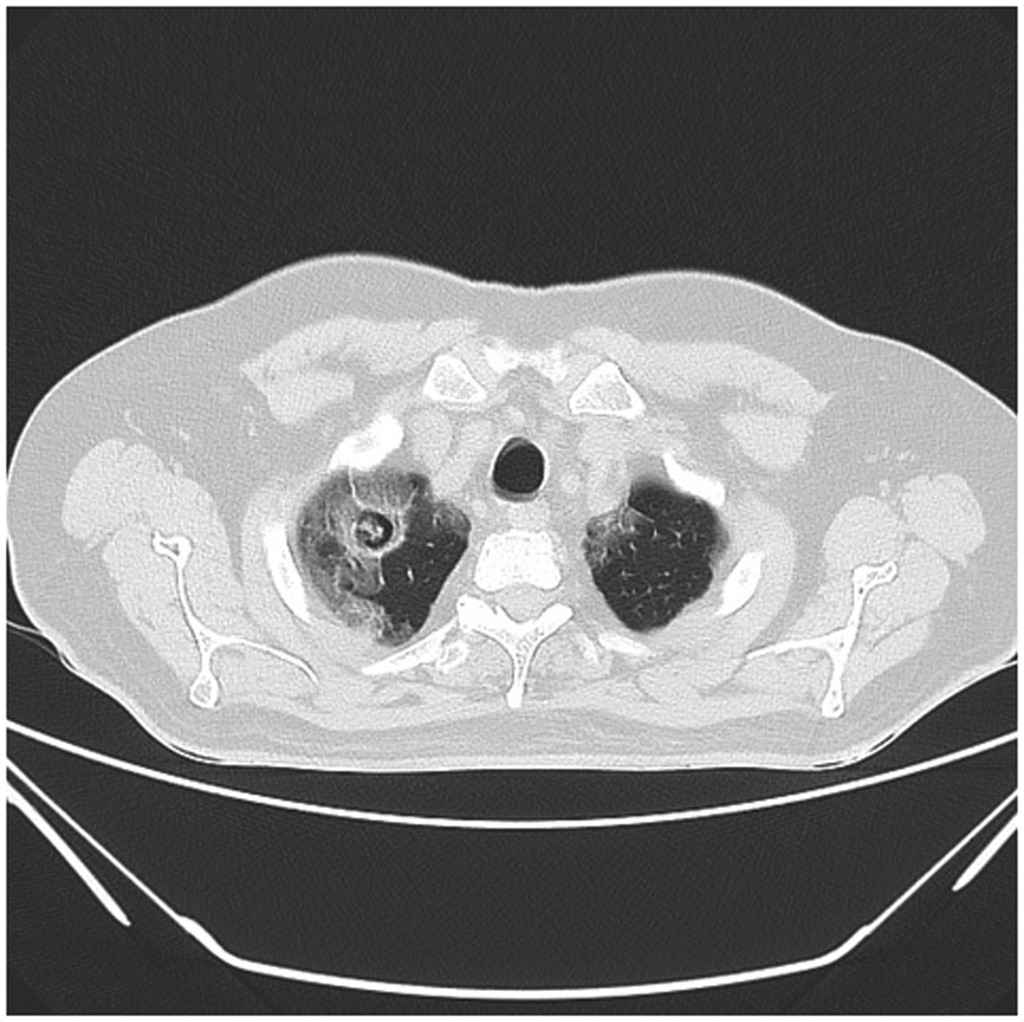

Aspergilloma and CCPA arise most often in immunocompetent individuals with pre-existing structural lung disease. Worldwide prevalence is highest among those with residual lung cavities due to TB; approximately 10% of pre-existing tuberculous lung cavities will develop aspergilloma.[6][7] In addition to TB, those with non-tuberculous mycobacteria, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and lung cancer represent high prevalence groups. SARS-CoV-2 pneumonitis is a recently recognized cause of aspergilloma, and several cases have been reported (see Image. HRCT Showing Characteristic Fungal Ball of Aspergilloma with Features of SARS-CoV-2 Pneumonitis).[8][9][8]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of CPA varies, with a lower prevalence of less than 1 case per 100,000 people in developed countries like the United States. The prevalence can be as high as 42.9 per 100000 in some African nations. This is likely due to the higher prevalence of tuberculous pulmonary cavities in populations from resource-poor areas of the world.[10] Aspergilloma incidence in patients with CPA is about 25%. The estimated global 5-year period prevalence is 18/100000.[11] That translates to a global burden of 1.2 million patients with a higher reported incidence and prevalence in Africa, the western Pacific, and Southeast Asia.[11] In resource-rich countries with a low prevalence of TB, the major risk factor for CPA is COPD. Isolated aspergilloma without preexisting parenchymal disease is much rarer, reported at 0.13%. Interestingly, though invasive aspergillus disease is more common in patients with primary or acquired immunodeficiency, the incidence is uncommon in HIV-infected patients.[12]

Pathophysiology

Human lungs constantly have exposure to airborne fungus, a relatively ubiquitous component of our external environmental microbiome. Of all fungal organisms, aspergillus with species fumigatus and niger are common colonizers. Aspergillus spores primarily enter the respiratory tract and the external auditory canal. These filamentous organisms rapidly multiply and become consequential in patients with a diseased lung or systemic immunodeficiency.

Aspergillomas can thrive in a poorly drained and avascular cavitary space. Within cavitary airspace, the organism adheres to the wall with its conidia, germinates, and, in the process, evokes an inflammatory reaction. Aspergilloma and CCPA do not tend to invade the surrounding lung tissue. The organism and the inflammatory debris form an amorphous mass defined as an aspergilloma. An ulceration or irregular cobblestoned cavity wall or floor may be the only pathological finding in the early stages. With advanced disease, aspergilloma is mobile within the cavity, which can be visualized in imaging.

Hemoptysis is the most common clinical manifestation in symptomatic patients. The bleeding source is usually a bronchial vessel and secondary to:

- Direct invasion of capillaries of the wall lining

- Endotoxin release from the organism

- Mechanical irritation of exposed vessels within the cavity

- A rapidly growing cavity that can erode into the pleural surface and intercostal arteries, causing massive, often fatal hemoptysis highly challenging to control.

An aggressively growing aspergilloma increases the chances of exposure and erosion into the broader pulmonary arterial system. Triggered by hypoxia, inflammation, and architectural distortion, an opening of the pulmonary and bronchial arterial anastomotic plexus is a target of erosion and hemoptysis.

As noted earlier, overlap in clinical features is possible. Multiple fungus balls can develop, particularly in patients with chronic cystic bronchiectasis or multicystic bullous disease. Occasionally, aspergilloma may develop within the bronchial tree (endobronchial aspergilloma) or the pleural space in chronic empyema.[13]

Histopathology

The organism is characterized by septate hyphae with dichotomous branching and long conidiophores carrying numerous spores on their tips. In a histologic specimen, aspergilloma appears as a mesh of inflamed, bloated septate hyphae, fibrin, blood clots, cellular debris, and mucous residues. The central core is often necrotic. Although the lining of a simple aspergilloma could be ciliated epithelium, the epithelial lining is more often pseudostratified columnar or metaplastic squamous epithelium. Depending upon the severity of inflammation and the time course of progression, the walls can have evidence of chronic granulomatous inflammation, lymphoid follicles, endarteritis, ulceration, and fibrosis.

History and Physical

A generalized understanding of predisposition is recognized to specific forms of aspergillus-mediated disease. Individuals with atopy or a predisposition to hypersensitivity are more prone to obstructive bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Immunocompromised patients are predisposed to invasive aspergillus infections, while aspergilloma and other forms of CPA are more common in immunocompetent patients with preexisting lung disease. However, overlap between these predisposition categories exists. Patients with aspergilloma can develop a hypersensitivity response akin to ABPA.[14] A chronic aspergilloma that is unchanged over months to years can also transition to CCPA, CFPA, and invasive infection.

Aspergilloma and CCPA can present with a spectrum of clinical symptoms, from asymptomatic colonization of a pre-existing lung cavity to fatal hemoptysis. Moreover, patients with aspergilloma may present with symptoms due to their underlying lung disease (eg, bullous emphysema, bronchiectasis, cavitary TB, cystic fibrosis, lung tumor, sarcoidosis). Hemoptysis is the most common clinical presentation, occurring between 54% to 87.5% according to various case series.[15][16] Massive hemorrhage may occur in 30% of patients. The size of an aspergilloma, complexity of the lesion, underlying predisposing lung disease, or prior minor hemoptysis are not predictive of developing massive hemoptysis.[17][18] Fever is rare, although symptoms of cough, chest pain, malaise, and weight loss may occur in patients with CCPA. If the organism invades the surrounding parenchyma, recurrent pneumonia, chronic cough, or pulmonary fibrosis can occur.[19]

Evaluation

A presumptive diagnosis of aspergilloma and CCPA is made based on characteristic radiographic features in patients with known underlying lung disease. It is occasionally discovered as an incidental radiographic finding in asymptomatic people. Once identified radiographically, additional criteria used to help establish the diagnosis include the presence of Aspergillus organisms in lower airway cultures obtained by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), positive serum or BAL galactomannan test, and serum Aspergillus-specific IgG antibodies.

Patients harboring a simple aspergilloma are not immunocompromised and have minor or no symptoms related to the fungus ball. Aspergilloma may be suspected by findings on chest X-rays or CT scans in patients being evaluated for symptoms related to their underlying primary pulmonary diseases. For example, aspergilloma may be suspected based on radiographic findings in patients with a pre-existing TB lung cavity, bronchiectasis, tumor, or chronic lung abscess. Alternatively, hemoptysis due to the presence of an aspergilloma may prompt evaluation. The European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society and The Infectious Diseases Society of America, has published the most comprehensive guidelines for diagnosing and managing CPA, including aspergilloma and CCPA.[1][4]

A chest x-ray is often the first diagnostic test ordered in a patient presenting with symptoms. It may show upper lobe predominant cavitation, thickening, scarring, and occasionally a rounded mass-like opacity within the cavity. CT scan provides more delineation and has some characteristic features:

- The appearance of a solid spherical lesion within the cavitary space

- Halo sign of surrounding inflammatory reaction in the cavity wall

- The air crescent sign separates the fungus ball from the wall in the entire or part of its circumference. (Also present in lung abscess, hydatid cyst, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis)

- Monod sign is characterized by a change in the position of the fungus ball within the cavity, with a change in the patient's position during imaging.

CT helps in defining the cavity wall thickness, architectural distortion, and inflammation of the surrounding parenchyma and pleura, the relationship of the aspergilloma with surrounding blood vessels, and the nature of neovascularization both in lung parenchyma and parietal pleura. The upper lobe of either lung is the most common location, although the superior segment of the lower lobe can be involved.

Radiographic features of CCPA can demonstrate areas of consolidation associated with 1 or multiple cavities of varying wall thickness that contain aspergilloma. Adjacent pleural thickening is common. Simple aspergilloma can transition to CCPA, and both can evolve into the fibrotic and subacute invasive forms of CPA.[20]

Radiographs provide a presumptive diagnosis. The finding of Aspergillus organisms in sputum is not diagnostic because the fungi are ubiquitous and can colonize the airway without causing disease. However, in patients with characteristic radiographic findings, the organisms from BAL further support the diagnosis. Conversely, the absence of organisms in the culture does not preclude a diagnosis. The significance of molecular tests conducted in bronchoscopy is still uncertain.

When characteristic radiological features are present, aspergillus-specific IgG antibodies in serum provide strong presumptive evidence of CPA. Patients who acquired their infection in Pakistan, where both A flavus and A fumigatus predominate, can have negative serum serology tests unless species-specific assays are utilized.[21] Assay against galactomannan antigen—a polysaccharide component of the fungal cell wall, has high specificity. Usually, the sensitivity of galactomannan antigen is more elevated in BAL fluid than in serum. False positive results can occur in patients prescribed piperacillin-tazobactam; false negative results can occur with high-dose steroid therapy. IgG antibodies against Aspergillus species diagnosed by precipitin assay are positive in over 90% of cases. Aspergillus IgG titers are typically high in those with CPA, and the titer slowly decreases (rarely becoming undetectable) with therapy.[22][23]

Aspergilloma and CCPA can occur contemporaneously with active lung processes, including neoplasm and other infectious disease etiologies.[24][25][26] These additional etiologies should be considered when evaluating patients with presumed aspergilloma and CCPA.

Treatment / Management

The management of CPA has not been standardized. Several aspects of treatment remain controversial due to the unpredictable course of infection and the limited experience with management approaches.[13] Most published studies are small case series and anecdotal case reports, and they do not clearly distinguish between the different types of CPA. Treatment goals are to alleviate symptoms, prevent and minimize episodes of hemoptysis, and prevent progression to pulmonary fibrosis.

Approximately 10% of simple aspergilloma can undergo spontaneous regression, while a significant number can cause massive hemoptysis.[2] Moreover, the ability to predict the severity of hemoptysis based on symptomatic versus asymptomatic presentation, aspergilloma size, extent, and associated underlying lung disease is limited.[2] Data suggests that the incidence and severity of hemoptysis are similar between simple and complex aspergilloma (the definition of complex aspergilloma is vague and likely encompasses CCPA).[2] An episode of minor hemoptysis predicts subsequent massive hemoptysis in 30% of patients.[27]

Surgical resection, long considered the gold standard, can be associated with high morbidity and mortality, and antifungal therapy has been considered of limited value. The surgical and medical team's experience, or lack thereof, can impact the management outcome, and this needs to be considered when evaluating published case series. While guidelines have been developed, controversy persists about management approaches, particularly in asymptomatic patients.[1][2][4] The Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends conservative, ongoing observation in asymptomatic patients with a single, stable aspergilloma. Should symptoms develop, including hemoptysis, resection is advised without contraindications. Peri-/postoperative antifungal therapy should be considered if a risk of surgical spillage exists. In patients considered high-risk surgical candidates and in those reluctant to undergo surgery, prolonged courses of triazoles are recommended.

While surgical resection is considered the mainstay of therapy, it is important to recognize that, due to poor general health, low pulmonary reserve, and the presence of extensive disease, not all patients with aspergilloma are suitable surgical candidates. Before the development of triazoles and echinocandins, systemic antifungal therapy had a limited role in management. More recent experience with triazole and echinocandin therapy has demonstrated therapeutic benefits in patients deemed inoperable.[28] In patients with symptomatic CCPA, oral triazole therapy is now the standard of care.[1] Guidelines recommend an initial 4 to 6-month course of oral triazole therapy. The duration should be extended for those who demonstrate slow or minimal response. Despite the lack of robust long-term data, it may be worth considering lifelong triazole suppression, though no firm recommendations are recognized.

An alternative form of antifungal therapy should be considered for those who do not respond or are intolerant to oral triazole therapy. Triazole resistance can develop during prolonged administration. Systemic administration of amphotericin B desoxycholate has not been shown to provide significant benefits, likely due to its associated toxicities. In small published studies, intravenous (IV) liposomal amphotericin and IV echinocandins have demonstrated clinical benefits.[1] They should be considered options for patients who do not respond, are intolerant, or have triazole-resistant organisms.

In non-surgical candidates who experience recurrent hemoptysis and patients not responding to systemic antifungal therapy, consideration should be given to the intracavitary installation of antifungal agents. Depending on the cavity size and location, pulmonary status of the patient, and the medical team's experience, intracavitary antifungal installation can be performed via an endobronchial or percutaneous catheter. [29][30][28] These should be considered short-term measures for therapy, and complications can include pneumothorax and cough. Transbronchial removal of aspergilloma is a non-surgical approach that has recently shown promise in selected patients.[31][32][31] Its application and value in management await further review.

In patients experiencing mild to moderate hemoptysis, administering oral tranexamic acid to stabilize clot formation could be attempted.[33] Antifungal therapy may prevent the recurrence of hemoptysis. In the setting of massive hemoptysis, bronchial artery embolization by interventional radiology has proven successful in 50% to 90% of events; however, recurrent rates of hemoptysis are high.[34] Subsequent antifungal therapy should be initiated. Embolization of internal mammary, subclavian, and lateral thoracic arteries may also be required to control hemoptysis. Embolization of arteries near the origin of spinal and vertebral arteries should be avoided due to the potential for causing spinal cord infarcts and paralysis.[35] Recent data from centers with experienced surgical teams report operative mortality between 0.9% and 3.3% and morbidity of 23.6% to 33.3%.[36][37] The decision to undergo surgery must be individualized, and consideration must be given to several factors, including:

- The patient's overall functional status and pulmonary reserve

- The experience of the surgical team

- The presenting symptoms

- asymptomatic

- cough

- chest pain

- weight loss

- presence or absence of hemoptysis and the degree of hemoptysis

- An indeterminate diagnosis and possible underlying neoplasm

The different approaches to surgery include lobectomy, pneumonectomy, segmentectomy, cavernectomy, and pleurectomy. Video-assisted thoracoscopy is a valuable approach in select patients.[22] Surgical complications include bronchopleural fistula, pneumonia, empyema, respiratory failure, hemorrhage, and death. Surgical removal of a simple aspergilloma is considered curative. If intraoperative spillage of the cavity contents or inability to remove the entire aspergilloma occurs, a postoperative course of antifungal therapy is suggested.[1] However, the duration of antifungal treatment in the postoperative setting is empiric and individualized.

Removal of a simple aspergilloma is considered curative. Complex aspergillomas and CCPA require prolonged courses of antifungal therapy, and a cure is sometimes unattainable. The goal in these cases is to stabilize the disease and reduce hemoptysis. Follow-up should include chest CT scans at 3 to 6-month intervals initially. If the radiographic findings stabilize or improve, their frequency can be reduced.[38] Serial Aspergillus-IgG serology should also be obtained. Declines in antibody titers should accompany response to therapy.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of a space-occupying lesion within a lung cavity includes:

- Primary lung malignancy

- Metastatic disease

- Aspergilloma

- Hydatid cyst

- Lung abscess

The differential diagnosis of CCPA includes:

- Active TB

- Non-tuberculous mycobacteria

- Histoplasmosis

- Coccidioidomycosis

- Actinomycosis

- Neoplasm

Prognosis

The prognosis of aspergilloma and CCPA is impossible to quantify given its unpredictable history, variables such as associated lung diseases, and the functional status of the patient. Spontaneous resolution occurs in approximately 10% of cases of simple aspergilloma. The recent availability of triazole and echinocandin antifungal agents in symptomatic patients suggests that benefits can be achieved in about 65% of those treated. Similar benefits have been attributed to the intracavitary instillation of antifungals. The impact of these modalities on long-term prognosis has not been evaluated, and symptomatic benefits do not necessarily correlate with life expectancy. The mortality estimate for those experiencing massive hemoptysis from any cause has historically been reported to be as high as 38%.[39] It is unclear if the figure is relevant to current management strategies for aspergilloma and CCPA. After successful bronchial artery embolization, the recurrence of hemoptysis occurs in 19% to 55% of cases.[28] The impact of new antifungal agents and non-surgical management on the prognosis of aspergilloma and CCPA needs further clarification.

Complications

Hemoptysis is the most common and feared complication. Complications associated with the underlying lung disease are expected. Potential complications are related to antifungal agent use administered systemically or by intracavitary installation. Possible intraoperative and postoperative complications are described above and must be taken into account when assessing preoperative risk on an individual basis. The natural history of simple aspergilloma and CCPA are poorly understood. They can remain relatively quiescent or transition to cause more extensive and invasive lung pathology.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Given the association with pre-existing TB lung cavities, the highest prevalence of aspergilloma and CCPA occurs in resource-poor parts of the world where limitations for diagnosis and treatment are high. Irrespective of geographic locale, once patients with aspergilloma and CCPA are identified, their options for management may be limited based on available resources and the experience of the team involved in their care. Therapeutic options may be limited due to the patient's poor functional and pulmonary status. Should antifungal therapy be selected as the treatment strategy, it often requires prolonged courses of therapy. This will significantly impact cost considerations and the monitoring of potential side effects. Moreover, once treatment is initiated, it should be anticipated that close follow-up will be needed over many years to assess therapeutic response. The decision to pursue surgery should account for the surgical team's experience.[2]

Managing aspergilloma and CCPA has evolved over the past decade, given the availability of new antifungal agents and alternative non-surgical and surgical therapy strategies. Due to the relatively low prevalence of the disease, particularly in developed regions of the world, many clinicians have limited experience. Contributing to their limited experience, many clinicians have been influenced by somewhat out-of-date studies in the medical literature. Controversy exists surrounding certain therapeutic and follow-up strategies and a lack of clinical studies. These deterrents complicate diagnosing and managing a very complicated infectious disease.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Aspergilloma and CCPA are disease entities subsumed under the broader heading of CPA. Preexisting lung disorders most often accompany these infectious diseases. Worldwide, the most common association occurs in patients with TB. The diagnosis entails demonstrating characteristic radiographic features and presenting microbiological studies and/or immunological evidence of Aspergillus species. Once the diagnosis is established, evaluation of the patient's functional and pulmonary status and the presence or absence of symptoms related to the fungus must be carefully evaluated. Individualized management options, including conservative observation, anti-fungal administration, or surgical intervention, should be considered. It is important to consider the financial burden on patients when developing follow-up strategies for short and long-term treatment options, especially if the current therapy is ineffective or not tolerated. If complications ensue, particularly hemoptysis, it is crucial to have immediate medical evaluation and treatment resources available.

All of the above requires a coordinated effort by the healthcare team. Expertise in radiology, infectious diseases, pulmonary and critical care, thoracic surgery, emergency medicine, and interventional radiology is required. In addition, pharmacists who are knowledgeable about administering oral, IV, and intracavitary antifungals are critical elements of the multidisciplinary team, as are radiology technicians, inpatient, operating room, and outpatient nurses.

Education of the team is pivotal in the decision-making process. This is particularly relevant given the challenges of evaluating a lack of robust evidence-based studies to create guidelines. Moreover, the educational component should acknowledge that, at the current time, evidence-based data concerning essential management questions is lacking. Virtually all decisions about diagnosing, managing, and follow-up of patients with aspergilloma and CCPA require close communication and coordination between a sizeable multidisciplinary healthcare team.